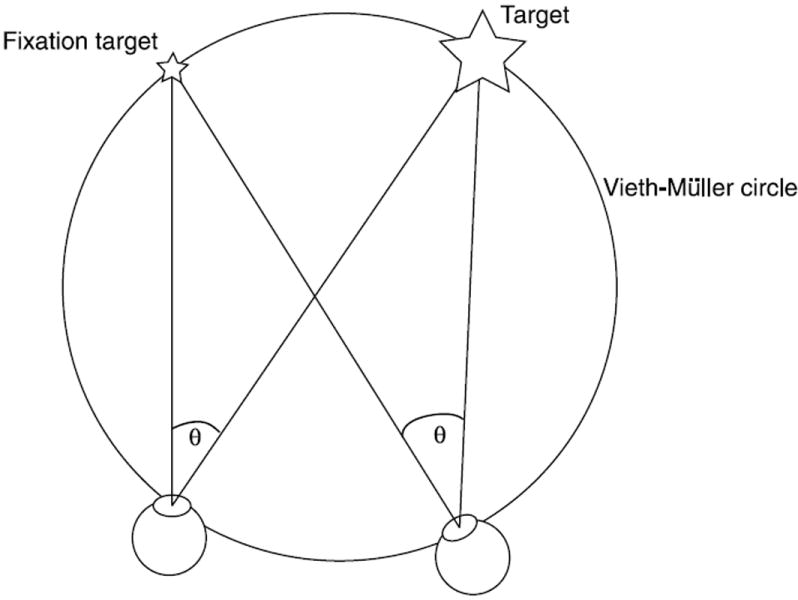

Figure 1.

Top-down view of the eyes and targets. We defined each target’s retinal eccentricity (θ) using the angle between the target center and fixation point relative to each eye so that the eccentricity was the same for both eyes. Targets were always placed on (or, in Experiment 3, relative to) the Vieth-Müller circle, the circle that passes through the fixation point and the nodal points of the eyes and forms the theoretical horopter. Alternatively, the horopter can be determined empirically (see Howard and Rogers (2002) and Schreiber, Hillis, Filippini, Schor, and Banks (2008)); the empirical horopter is slightly different from the theoretical horopter and varies in shape across individuals (Blakemore, 1970; Schreiber et al., 2008). There are tradeoffs between the two definitions in their assumptions and ease of measurement; we chose to use the Vieth-Müller circle because it allowed us to more easily define the positions of the targets and satisfy the geometric constraints that the experiments required. Panum’s area (not shown) is the region about the horopter where binocular fusion is possible.