Summary

Atherosclerosis is a disease characterized by excess cholesterol and inflammation in the blood vessels. The liver X receptors (alpha and beta) are members of the nuclear hormone receptor family that are activated by endogenous cholesterol metabolites. These receptors are widely expressed with a tissue distribution that includes the liver, intestine and macrophage. Upon activation, these receptors have been shown to increase reverse cholesterol transport from the macrophage back to the liver to aid in the removal of excess cholesterol. More recently, they have also been shown to inhibit the inflammatory response in macrophages. These functions are accomplished through direct regulation of gene transcription. Herein, we will describe the key benefits and potential risks of targeting the LXRs for the treatment of atherosclerosis.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, LXR, cholesterol, ABCA1, reverse cholesterol transport, SREBP-1c, inflammation, liver, adrenal gland, brain, lung

Introduction

Diseases Associated with Cholesterol Imbalance

Cholesterol is essential for maintaining proper fluidity of cellular membranes and as a precursor for steroid hormones, two roles critical for survival. Excess cholesterol, however, is associated with several chronic disease states including atherosclerosis.[1] In humans, the liver is able to synthesize de novo all the cholesterol needed for maintaining cellular growth and whole body homeostasis, therefore, cholesterol is not required from the diet.[2] However, the popularization of the Western-style (high fat and high cholesterol) diet has made controlling the intake of dietary cholesterol in industrialized countries increasingly difficult.

Cholesterol can be transported by high density lipoproteins (HDL or “good cholesterol”) and low density lipoproteins (LDL or “bad” cholesterol). The presence of cholesterol on either of these lipoprotein subsets essentially describes the direction of flow of cholesterol in the body. LDL is the main carrier of cholesterol in the blood and as such is responsible for cholesterol delivery to tissues. In contrast, HDL helps to remove cholesterol from the periphery, including macrophages, and returns it to the liver where it is eliminated through metabolism and secretion into the bile. Therefore, while elevated total cholesterol has been strongly linked to atherosclerosis, large epidemiological studies have also found that elevated LDL levels and low HDL levels are independent risk factors for coronary heart disease.[3–6] HDL-cholesterol is thought to be cardioprotective mainly because of its role in reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) to the liver.[7, 8] However, HDL may be further beneficial because it contains anti-oxidant properties[9, 10] which can help to protect against oxidation of LDL, an important initial step in promoting cholesterol uptake by arterial macrophages. In diseases such as atherosclerosis, LDL and oxidized LDL accumulate in lesions and contribute to the transformation of endothelial cells and macrophages into foam cells- the major component of atherosclerotic lesions.[11, 12] Figure 1 follows the flow of cholesterol in an atherosclerotic plaque from the delivery of cholesterol in LDL, uptake into macrophages and removal of cholesterol through efflux to HDL. HDL can be considered the transport vessel that carries cholesterol to the liver for elimination.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the role of LDL (yellow) in contributing to atheromatous lesion production. In the atherosclerotic plaque, there is a buildup of LDL as well as the transformation of smooth muscle cells and macrophages into foam cells through the uptake of cholesterol carried by oxidized LDL. In contrast, efflux of free cholesterol is achieved from macrophage cells to help alleviate lipid accumulation and prevent foam cell formation. The cholesterol is effluxed to pre-β-HDL (green) particles that carry the cholesterol back to the liver for elimination. HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; ox-LDL, oxidized low density lipoprotein; C, cholesterol; CE, cholesterol ester.

Inflammation has been recognized as a critical component appearing alongside the accumulation of lipids in the blood vessel in the progression towards atherosclerosis.[12] Inflammation also represents a common unifying link with other diseases characterized by a lipid imbalance including Alzheimer’s disease[13], diabetes[14], glomerular nephropathies[15], and asthma[16]. The role that the LXRs may play in contributing to all these conditions will be described below.

The Nuclear Hormone Receptors LXRα and LXRβ

Nuclear hormone receptors are transcription factors that consist of highly conserved domains including a zinc-finger DNA-binding domain and a hydrophobic ligand-binding domain. The liver X receptors alpha and beta are two members of the 48-member human nuclear hormone receptor superfamily. LXRα and LXRβ are activated by intracellular metabolites of cholesterol (called oxysterols).[17] Activated LXRα and LXRβ in turn initiate gene transcription from specific DNA sequences to control global patterns of gene expression involved in cholesterol balance.[18, 19] LXRα and LXRβ activate transcription as heterodimers with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) through specific DNA binding elements consisting of direct repeats of the canonical hexanucleotide sequence AGGTCA with a 4 nucleotide spacer (DR4).[20] It is not uncommon to find RXR/LXR heterodimers already bound to DR4 elements in the absence of ligand. Under these conditions, the receptors are bound to corepressors and can actively repress gene transcription. However, when ligand is present, a conformational change in the activation function domain 2 (AF-2) occurs. Co-repressor proteins are displaced and co-activator proteins are recruited to help initiate gene transcription.[21] Figure 2 illustrates the intracellular mechanism by which these nuclear receptors activate downstream target genes.

Figure 2.

A. LXR and RXR associate as heterodimers on DNA and are activated by ligand (oxysterols or synthetic agonist). Upon ligand activation, co-repressors are dissociated and co-activators are recruited to initiate gene transcription. The DNA sequence of the response element and the ligands are described in B. LXR, liver X receptor; RXR, retinoid X receptor; DBD, DNA binding domain; LDB, ligand binding domain.

LXRα and LXRβ share ~77% homology in their DNA binding domains and ligand binding domains which explains the very similar substrate specificities and affinities for oxysterols.[19] Furthermore, the crystal structures of the ligand binding domains of these receptors have revealed that the same amino acids line the pocket in both receptors. [22]

LXRα is most highly expressed in the liver, kidney, intestine and adipose tissue, while the expression of LXRβ is detectable in every tissue tested at a fairly consistent level. When compared using real-time quantitative PCR, the expression of mouse LXRβ in the liver is approximately 2-fold less than that of LXRα, while in other tissues LXRβ is the predominant receptor.[23]

Despite the overlap in the tissue distribution of LXRα and LXRβ, numerous target genes identified to date have shown some isoform specificity. In the liver, while both LXRα and LXRβ can bind to the DR4 response elements upstream of the cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (mouse Cyp7a1) and lipoprotein lipase (Lpl) genes in vitro, only LXRα is considered to contribute to the in vivo expression of both genes.[24–26] It has been suggested that tissue-specific factors, including regulatory proteins such as co-activators and co-repressors control the nuclear receptor isoform selectivity at the chromatin level.[21, 27]

LXRs in Cholesterol Homeostasis and Immune Function

The interest in LXR as a potential drug target for atherosclerosis stems from the finding that activation of LXR increases the gene expression of target genes that promote excretion of cholesterol from the body. This approach would complement the already clinically successful strategies of decreasing total cholesterol levels through the inhibition of the rate limiting step in the hepatic de novo synthesis of cholesterol (i.e. inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase with statin drugs); or decreasing the absorption of excess dietary cholesterol in the small intestine, through the inhibition of the cholesterol uptake transporter NPC1L1 (with the drug ezetimibe).[28, 29] While these two strategies have proven successful at lowering total cholesterol, the unique aspect that is anticipated from LXR regulation is selectively enhancing reverse cholesterol efflux with simultaneous inhibition of inflammation and the potential to increase the ratio of HDL relative to LDL.

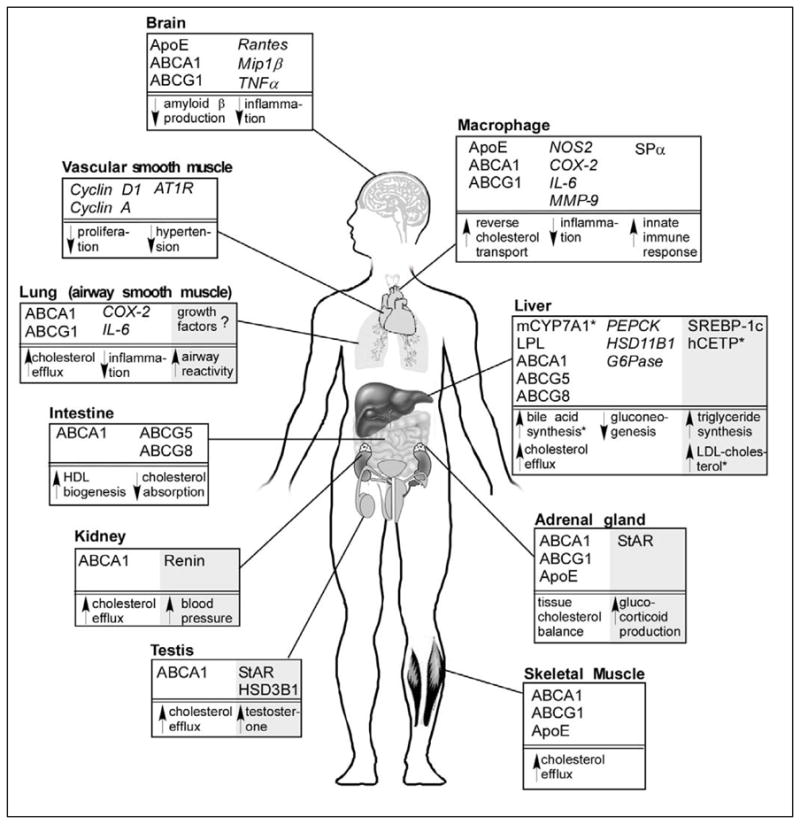

LXRα and LXRβ are transcription factors that are frequently termed the “master” regulators of cholesterol homeostasis because they regulate a myriad of genes that protect against excessive cholesterol loading in the cell. In addition, the LXRs play an important role in governing immune responses, particularly in macrophages. The gene targets for these responses vary depending on the physiologic systems and are described below, and summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Whole body overview of the effect of LXR activation on various tissues in the body. Positively regulated LXR target genes are highlighted for different tissues with negatively regulated genes shown in italics. Effects that are expected to be favorable for the treatment or prevention of atherosclerosis and other inflammatory conditions are shown in white. Potential negative side effects of activating LXR in various tissues are highlighted in gray. References for these effects of LXR are discussed in the text. Question marks indicate that target genes are unknown for the observed effect. ABC, ATP-binding cassette; ApoE, apolipoprotein E; AT1R, angiotensin II type 1 receptor; CETP, cholesterol ester transfer protein; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; CYP7A1, cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase; G6Pase, glucose 6-phosphatase; HSD, hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; IL-6, interleukin 6; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; Mip1β, macrophage inflammatory protein 1β; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; NOS-2, nitric oxide synthase 2; PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase; SPα, also called AIM (apoptosis inhibitor expressed by macrophages); SREBP-1c, sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c; StAR, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α.

i) Enterohepatic system

LXR was first found to play a critical role in cholesterol homeostasis from experiments performed in Lxrα−/− mice. These mice, when fed a high-cholesterol diet, developed massive fatty livers due to accumulation of cholesterol esters in the liver.[25] Cholesterol is excreted from liver through two pathways, conversion to bile acids or direct efflux into bile. The rate-limiting step in the conversion of cholesterol into bile acids is governed by CYP7A1. LXR directly regulates the murine Cyp7a1 gene at the transcriptional level.[25] As a result, Lxrα−/− mice not only accumulated hepatic cholesterol but also have a reduced bile acid pool size and fecal bile acid loss. (ABC) transporters that govern cellular efflux of cholesterol, including ABCA1, ABCG1, ABCG5 and ABCG8.[31–38] ABCG5 and ABCG8 are the major LXR target genes responsible for cholesterol efflux in both liver and small intestine.[33, 38] The identification of the sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c (SREBP1c) as an LXR target gene directly linked fatty acid synthesis with dietary cholesterol intake.[39] More recently, LXR has been implicated as a negative regulator in the control of hepatic glucose production. Activation of LXR has been shown to decrease plasma glucose levels in diabetic animal models without affecting basal glucose levels in wildtype animals.[40–42] The glucose-lowering effect is thought to be at least partially through direct transcriptional repression of the rate-limiting enzyme in gluconeogenesis, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK); as well as through inhibition of glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) and 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD11B1).[42–45] These recent findings have highlighted the similarities between LXR activation and insulin action. Like insulin, LXR activation increases SREBP-1c (and promotes triglyceride synthesis) while repressing hepatic gluconeogenesis.

The liver plays a central role in mediating reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), since cholesterol from peripheral tissues is returned to the liver and then converted to bile acids or directly secreted to the bile for eventual removal in the feces. ABCG5 and ABCG8 function as heterodimers and facilitate cholesterol transport from liver to bile. They are also induced by LXR agonist in small intestine, where they transport dietary phytosterols back into the intestinal lumen. Mutations in these genes cause “sitosterolemia” which is characterized by high levels of plant sterols in plasma.[46] Since ABCG5 and ABCG8 are also able to transport cholesterol, activation of these transporters results in reduced cholesterol absorption.[38] In fact, the activation of ABCG5 and ABCG8 in the liver may not be the only contributor increasing cholesterol removal as direct excretion of cholesterol from the intestine has recently been observed.[47, 48] Expression of ABCA1, another cholesterol transporter, is also dramatically induced by LXR in the intestine[34] where it appears to be localized more on the basolaterol membrane of enterocytes.[49, 50] Since its role in cholesterol efflux to lipid-poor lipoproteins has been established, ABCA1 may contribute to HDL biogenesis in the intestine. A recent study performed in mice using an LXR agonist to selectively activate ABCA1 in the intestine demonstrated that an increase in HDL cholesterol could be achieved systemically without altering plasma triglycerides and that this effect was dependent on ABCA1.[51] Thus, LXR activation in the intestine may favorably contribute to cholesterol balance through two independent transporter systems.

ii) Hematopoietic and vascular system

Macrophage cholesterol efflux contributes significantly to the process of reverse cholesterol transport and is particularly important in the prevention of atherosclerosis. Accumulation of esterified cholesterol in these cells in the arterial wall leads to foam cell formation, an initial step in atherogenesis (Figure 1). Several LXR target genes are involved in macrophage cholesterol efflux including APOE, ABCA1 and ABCG1. ApoE is selectively regulated by LXR in macrophages and adipose tissue.[52] ApoE is a component of nascent HDL particles and may serve as an acceptor in the ABCA1 efflux pathway. Studies using bone marrow transplant from wildtype or LXRαβ-null mice in to ApoE−/− or Ldlr−/− mice unequivocally established that LXR activation was protective against atherosclerosis.[53–55] ABCA1 is required for Apo-A1-mediated cholesterol efflux and ABCG1 has been shown to play a role in cholesterol and phospholipid efflux.[35, 56–58] The combined deficiency of ABCA1 and ABCG1 has recently been shown to promote atherosclerosis in mice. Recent elegant cholesterol radiotracer studies have been performed in three different animal models pre-treated with LXR agonists all showing that LXR activation does indeed result in the increased movement of macrophage cholesterol to the feces.[59]

Atherosclerosis is characterized not only as a disorder in lipid metabolism but also as a chronic inflammatory disease.[12] As such, macrophages are also central mediators in the inflammatory component of atherosclerosis.[60] Several studies have demonstrated that LXR activation inhibits expression in macrophages of inflammatory genes, such as NOS2, COX-2, IL-6 and MMP-9.[61, 62] Furthermore, bone marrow transplantation from Lxrα/β−/− mice to WT mice demonstrated that mice lacking LXRs are highly susceptible to infection by Listeria monocytogenes. This susceptibility is thought to be due to the loss of regulation of the macrophage LXRα target gene, Spα, which encodes an anti-apoptotic factor.[63] These studies uncovered an entirely new role for LXR in integrating the inflammatory and lipid metabolic pathways and provided further evidence that targeting LXR would be beneficial for the treatment of atherosclerosis.

LXR activation is also thought to be anti-atherogenic because of its role in vascular smooth muscle cells. It is known that activation, migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells after injury is a contributing factor in the development of atherosclerosis and blood vessel occlusion. In a rat model of balloon-injured carotid artery, administration of the LXR agonist T091317 prevented vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointima formation.[64] In vitro studies with human vascular smooth muscle cells found that LXR agonist inhibited the G1 to S transition of the cell cycle at least partially though decreased expression of cyclin D1 and cyclin A.[64] It was recently shown that the angiotensin II receptor AT1R is also repressed in rat vascular smooth muscle cells by LXR activation.[65] Since activation of AT1R by angiotensin II contributes to hypertension, and atherosclerosis and AT1R antagonists are protective against atherosclerosis, the downregulation of AT1R by LXR provides another mechanism by which LXR activation is beneficial for the treatment of atherosclerosis.

iii) Steroidogenic system

Recent studies from our lab and others have shown that LXRα is also important in the regulation of adrenal gland cholesterol balance.[66–68] Cholesterol is the precursor to all steroid hormones including glucocorticoids (such as cortisol and corticosterone), which are rapidly produced under conditions of acute stress. Under basal conditions, the cellular cholesterol concentration is tightly regulated by efflux and storage as cholesterol esters. LXRα-null mice displayed adrenomegaly and increased plasma corticosterone levels. StAR, a rate-limiting enzyme in steroidogenesis has been identified as a direct target gene of LXRα. Loss of LXRα de-repressed the expression of StAR, resulting in increased secretion of corticosterone. Enlarged adrenal glands observed in the Lxrα/β−/− mice were due to cholesterol accumulation in the cortex by the loss of regulation of ABCA1 and ABCG1. Lxrα/β−/− mice placed on a Western diet, a chronic dietary stress, developed adrenals containing more free cholesterol and cholesterol esters than WT mice. Activation by LXR agonist significantly increased the expression of StAR, SREBP1c and APOE, thus also resulting in increased steroid hormone production.[66] These studies established the role of LXRα in the adrenal gland under both basal condition and chronic stress – to prevent free cholesterol accumulation by maintaining the balance among steroid hormone synthesis, cholesterol storage and efflux.

LXR-null mice have been shown to have reduced fertility.[69–71] In contrast to the selective role of LXRα for maintaining cholesterol balance in the adrenal gland, LXRβ was found to be important for lipid homeostasis in the testis. However, LXRα-null mice had lower testicular testosterone levels and a higher rate of apoptosis.[69, 71] In wildtype mice treated with LXR ligand, StAR and HSD3B1 were increased resulting in elevated testicular testosterone. The different roles of the LXRs in these steroidogenic organs are thought to be due to the presence of tissue specific cofactors.

LXR activation is also protective against estrogen-dependent breast cancer. This effect is thought to be due to the decrease in circulating estrogen due to the LXR-dependent induction of the estrogen sulfotransferase metabolizing enzyme SULT1E1.[72]

iv) Central nervous system

Increasing evidence points to an association between cholesterol metabolism in the CNS and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The major pathway of cholesterol elimination in the brain is the conversion of cholesterol to 24S-hydroxycholesterol.[73] Concentrations of 24S-hydroxycholesterol in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid are significantly higher in AD patients.[74] Lehmann et al.[24] first identified 24S-hydroxycholesterol as an LXR ligand. LXR target genes APOE and ABCA1 have been implicated to play a role in the pathogenesis of AD.[75–77] Several studies have shown that LXR agonist treatment induces LXR target gene expression, enhances cholesterol efflux and reduces amyloid beta production both in vitro and in vivo.[76, 78, 79] A recent study also suggested that the ability of LXR to inhibit neuroinflammatory responses contributes to the effect of LXR to attenuate AD pathology.[80] These results identify LXR as a promising potential target for the treatment of AD.

v) Skeletal muscle

Skeletal muscle represents a major organ involved in nutrient metabolism including glucose utilization and fatty acid oxidation. Studies by Muscat and colleagues[81] demonstrated that skeletal muscle was subject to regulation by LXR agonists in vivo resulting in the activation of ABCA1, ABCG1 and ApoE. Furthermore, activation of muscle cells in vitro by a pan-LXR agonist resulted in increased cholesterol efflux. This effect may be substantial because muscle accounts for ~40% of body mass.

vi) Lung and kidney

In agreement with LXR’s ability to inhibit the immune response in macrophage cells, Delvecchio et al[82, 83] have recently shown that activation of LXR in airway smooth muscle cells can also inhibit chemokines and enhance cholesterol efflux from this cell type. These findings provide a potential pathway to target inflammatory airway diseases including asthma.[84] However, conflicting results have been shown with respect to the effect of LXR activation on the growth of airway smooth muscle cells.[83, 85] Using an in vivo model of allergic inflammation, LXR activation caused an increase in airway reactivity due to increased smooth muscle thickness.[85]

In the kidney, LXRα is required for adrenergic stimulation of renin expression in juxtaglomerular cells, whereas LXRβ constitutively activates renin.[86] Changes in the levels of LXR could therefore lead to alterations in blood pressure and salt-volume homeostasis. Proctor et al.[87] found renal lipid accumulation in Type I diabetes coincided with decreased expression of LXRα, LXRβ, and the target gene ABCA1; and increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Studies aimed at determining whether a reversal of this nephropathy can be achieved with LXR activation are still needed.

Benefits and Challenges of Targeting LXR for Therapeutic Modalities

The importance of providing a complementary pharmacological therapy to statin treatment for atherosclerosis cannot be underscored. Current therapies are successful at lowering total lipoprotein levels; however, these levels reach a plateau that for many is still unacceptably high.[7] While the risk for adverse cardiovascular events has significantly decreased with intensive statin therapy, it still remains at 9% per year for patients with established coronary artery disease.[7, 88] Targeting any of the well established pathways described herein are likely to provide beneficial effects but the advantage of targeting LXR is that multiple pathways can be targeted with a single molecule that would be expected to provide a multitude of beneficial effects.

To date, the major roadblock for the successful therapeutic targeting of LXR is the concurrent increase in triglyceride levels. LXR is a potent activator of the master regulator of fatty acid synthesis, SREBP-1c, and as such LXR activators have been shown to cause elevated plasma triglycerides and fatty liver [39]. In addition, Groot et al.[89] observed that LXR agonist increased LDL cholesterol in hamsters and cynomolgus monkeys. Unlike mice, these species are closer to humans and possess the CETP (choelsteryl ester transfer protein) gene, which reduces HDL-cholesterol and results in a more atherogenic lipoprotein profile. It has been shown that CETP is a direct target gene of LXR.[90] (Lou and Tall, 2000). There are two approaches that have been used to attempt to circumvent these undesirable effects: i) gene selective modulation and ii) LXR-isoform selective activation. LXRα has been more strongly implicated in the regulation of SREBP-1c. Although both LXRα and LXRβ can bind to the LXR response element for CETP in vitro[90], it is not yet known whether LXRβ-selective agonists will still induce CETP in vivo.

Use the gene selective approach, Quinet et al.[91] found that the compound DMHCA (a dual LXRα and LXRβ agonist) was able to selectively induce ABCA1 and not SREBP-1c both in vitro and in vivo. The result was an increase in macrophage cholesterol efflux without concurrent plasma or liver hypertriglyceridemia. Furthermore, Kratzer et al.[92]have recently shown that long-term treatment with DMHCA significantly reduces lesion formation in Apoe−/− mice. Unfortunately, this compound was only weakly orally active, preventing its further development. However, these data strongly support the hypothesis that gene-selective LXR modulators can be produced and provide good proof-of-concept for moving ahead with LXR as a therapeutic target in the treatment of atherosclerosis.

To test whet her LXRβ-selective agonists would be as effective as dual agonists for the treatment of atherosclerosis, studies were performed with dual agonists in Lxrα−/− mice and tested for target gene activation. The results from these experiments suggest this method will be promising as Lxrα−/− mice demonstrated strong macrophage ABCA1 induction and cholesterol efflux with ligand treatment.[93–95] Very recent studies performed in Lxrα−/−;Apoe−/− mice treated with a pan-LXR agonist (to activate LXRβ) found that after treatment, the atherosclerotic lesion area was diminished.[96] This provided the first unequivocal evidence that activation of LXRβ selectively will be a successful strategy to activate reverse cholesterol transport without increasing liver or plasma triglycerides. The decreases seen in atherosclerotic lesions in the Lxrα−/−;Apoe−/− may have been due to both an increase in reverse cholesterol transport and a decrease in the inflammatory response.[96] In addition, LXR agonist treatment also reduced plasma total cholesterol levels in these Lxra−/−;Apoe−/− mice, which may also have contributed to the reduced atherosclerotic lesions. This effect on total cholesterol has been observed in hypercholesterolemic mice and may be due to the effects of LXRβ in the intestine where increased expression of ABCG5/G8 can result in decreased cholesterol absorption. Progress has been made to generate LXRβ-selective ligands, a remarkable advance considering the amino acid residues lining the ligand binding pockets of LXRα and LXRβ are identical.[22] However, because of this considerable difficulty, it is unclear to what extent selectivity between the isoforms can be achieved and whether selectivity obtained from in vitro screening will be maintained in an in vivo setting. A further challenge will be to design LXRβ-selective ligands with pharmacokinetic properties amenable to development.

To date, virtually all of the data generated with LXR agonists have used the murine animal model. While many of the target genes of LXR have been confirmed to be regulated in human cells, a key remaining challenge is to determine whether similar activation of these pathways will occur in humans and provide the desired outcome for the treatment of atherosclerosis.

Conclusion

LXR is currently an attractive target for the treatment and prevention of atherosclerosis because of the perceived benefit of increasing RCT while decreasing inflammation. Current efforts have focused on developing compounds that activate the ABCA1 and ABCG1 transporters without activating SREBP-1c to eliminate the dose-limiting hypertriglyceridemia observed with pan-LXR agonists. A search of the online patent archives reveals LXR as the major subject matter of at least 31 patents. Despite very active pursuits by small and large pharmaceutical companies, the approval of the first LXR agonist for the treatment of atherosclerosis is still anxiously awaited.

Future Perspective

The success of targeting LXR for atherosclerosis and inflammatory disease will depend heavily on whether LXR-isoform selective modulators are discovered or partial agonists that have selectivity at the various promoter targets are identified with appropriate pharmacokinetic properties. There is promise that this is possible based on the generation of selective estrogen-receptor modulators for which both of the above criteria have been successfully demonstrated.

A unique approach to tissue selective activation of LXR that has already shown some success in the macrophage is through the tissue selective formation of an LXR ligand. Inhibition of oxidosqualene:lanosterol cyclase has been shown to be an effective method of selectively increasing ABCA1, ABCG1 and ApoE in macrophages without eliciting an increase in triglycerides.[97]

Targeting LXR therapeutically is attractive because it can positively affect more than one pathway involved in promoting favorable cholesterol balance. Recent outcome data indicate that the most impressive therapeutic results are achieved through combination therapy targeting multiple pathways (strong examples for this strategy have been seen in the treatment of HIV and cancer). For atherosclerosis, this could potentially be achieved through the development of a single compound targeting LXR that would improve two major components of atherosclerotic disease- preventing the buildup of excessive cholesterol via activation of RCT and inhibition of the inflammatory component contributing to disease progression. With the recent implication of LXR in regulating glucose metabolism and the tight correlation between metabolic disease and atherosclerotic risk, is it very tempting to speculate that targeting LXR could also achieve the added benefit of decreasing elevated plasma glucose.

Executive Summary

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is an arterial disease caused by excessive cholesterol in the blood vessels resulting in plaque formation and local inflammation.

A Western-style (high fat and high cholesterol) diet is a key contributing factor increasing the incidence of cardiovascular disease.

Nuclear Receptors LXRα and LXRβ

LXRα and LXRβ are transcription factors in the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that act as cholesterol sensors in the nucleus.

LXRα and LXRβ can be activated by endogenous oxidative metabolites of cholesterol (oxysterols) or by pharmacologic agents.

LXRs in Cholesterol Homeostasis and Immune Function

LXR activation induces a program of gene transcription that enhances the efflux of cholesterol from the periphery back to the liver (reverse cholesterol transport) and also inhibits inflammatory signaling molecules.

Genes regulated by LXR include several ABC transporters (ABCA1/ABCG1/ABCG5 and ABCG8) that serve to enhance the removal of cholesterol from cells.

Inflammation is attenuated after LXR activation by decreasing the expression of inflammatory target genes including: IL-6, COX-2 and NOS2.

Benefits and Challenges of Targeting LXR for Therapeutic Modalities

The key benefit to targeting LXR for atherosclerosis is the dual action of enhancing reverse cholesterol transport while also inhibiting inflammation.

To date, the dose-limiting toxicity associated with pharmacologic LXR activation is the increase in liver triglycerides caused by the activation of SREBP-1c. SREBP-1c is the master regulator of fatty acid synthesis.

Future Perspective

There is strong evidence to suggest that pharmaceutical companies will be successful at developing either an LXR isoform selective agonist or an LXR target gene selective agonist to overcome the current roadblock of hypertriglyceridemia associated with potent pan-LXR agonists.

LXR agonists may also prove to be beneficial for the treatment of other diseases associated with a lipid imbalance and inflammatory component including: Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, asthma, and advanced renal disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank David J. Mangelsdorf (UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX) for his helpful comments and suggestions. Research in the Cummins lab is supported by the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

References

- 1.Kannel WB, Castelli WP, Gordon T. Cholesterol in the prediction of atherosclerotic disease. New perspectives based on the Framingham study. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90(1):85–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-90-1-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vuoristo M, Miettinen TA. Absorption, metabolism, and serum concentrations of cholesterol in vegetarians: effects of cholesterol feeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59(6):1325–1331. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.6.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunner D, Weisbort J, Meshulam N, Schwartz S, Gross J, Saltz-Rennert H, et al. Relation of serum total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol percentage to the incidence of definite coronary events: twenty-year follow-up of the Donolo-Tel Aviv Prospective Coronary Artery Disease Study. Am J Cardiol. 1987;59(15):1271–1276. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90903-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Am J Med. 1977;62(5):707–714. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grundy SM. Atherogenic dyslipidemia: lipoprotein abnormalities and implications for therapy. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75(6):45B–52B. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(95)80011-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin MJ, Hulley SB, Browner WS, Kuller LH, Wentworth D. Serum cholesterol, blood pressure, and mortality: implications from a cohort of 361,662 men. Lancet. 1986;2(8513):933–936. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90597-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Targeting residual cardiovascular risk: raising high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Heart. 2008;94(6):706–714. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.125401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attie AD, Kastelein JP, Hayden MR. Pivotal role of ABCA1 in reverse cholesterol transport influencing HDL levels and susceptibility to atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2001;42(11):1717–1726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navab M, Hama SY, Anantharamaiah GM, Hassan K, Hough GP, Watson AD, et al. Normal high density lipoprotein inhibits three steps in the formation of mildly oxidized low density lipoprotein: steps 2 and 3. J Lipid Res. 2000;41(9):1495–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navab M, Hama SY, Cooke CJ, Anantharamaiah GM, Chaddha M, Jin L, et al. Normal high density lipoprotein inhibits three steps in the formation of mildly oxidized low density lipoprotein: step 1. J Lipid Res. 2000;41(9):1481–1494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Lipoprotein metabolism in the macrophage: implications for cholesterol deposition in atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1983;52:223–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.001255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glass CK, Witztum JL. Atherosclerosis. the road ahead. Cell. 2001;104(4):503–516. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casserly I, Topol E. Convergence of atherosclerosis and Alzheimer's disease: inflammation, cholesterol, and misfolded proteins. Lancet. 2004;363(9415):1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15900-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444(7121):860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chadban SJ, Atkins RC. Glomerulonephritis. Lancet. 2005;365(9473):1797–1806. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66583-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galli SJ, Tsai M, Piliponsky AM. The development of allergic inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):445–454. doi: 10.1038/nature07204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janowski BA, Grogan MJ, Jones SA, Wisely GB, Kliewer SA, Corey EJ, et al. Structural requirements of ligands for the oxysterol liver X receptors LXRalpha and LXRbeta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(1):266–271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalaany NY, Mangelsdorf DJ. LXRS AND FXR: The Yin and Yang of Cholesterol and Fat Metabolism. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:159–191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.033104.152158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Repa JJ, Mangelsdorf DJ. The role of orphan nuclear receptors in the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:459–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willy PJ, Umesono K, Ong ES, Evans RM, Heyman RA, Mangelsdorf DJ. LXR, a nuclear receptor that defines a distinct retinoid response pathway. Genes Dev. 1995;9(9):1033–1045. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.9.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner BL, Valledor AF, Shao G, Daige CL, Bischoff ED, Petrowski M, et al. Promoter-specific roles for liver X receptor/corepressor complexes in the regulation of ABCA1 and SREBP1 gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(16):5780–5789. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5780-5789.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molteni V, Li X, Nabakka J, Liang F, Wityak J, Koder A, et al. N- Acylthiadiazolines, a new class of liver X receptor agonists with selectivity for LXRbeta. J Med Chem. 2007;50(17):4255–4259. doi: 10.1021/jm070453f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bookout AL, Jeong Y, Downes M, Yu RT, Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Anatomical profiling of nuclear receptor expression reveals a hierarchical transcriptional network. Cell. 2006;126(4):789–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehmann JM, Kliewer SA, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, Oliver BB, Su JL, et al. Activation of the nuclear receptor LXR by oxysterols defines a new hormone response pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(6):3137–3140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peet DJ, Turley SD, Ma W, Janowski BA, Lobaccaro JM, Hammer RE, et al. Cholesterol and bile acid metabolism are impaired in mice lacking the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXR alpha. Cell. 1998;93(5):693–704. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Repa JJ, Gauthier K, Mangelsdorf DJ. Regulation of lipoprotein lipase by the oxysterol receptors, LXRalpha and LXRbeta. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(46):43018–43024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu X, Li S, Wu J, Xia C, Lala DS. Liver X receptors interact with corepressors to regulate gene expression. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17(6):1019–1026. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Endo A. The discovery and development of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. J Lipid Res. 1992;33(11):1569–1582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sudhop T, Lutjohann D, Kodal A, Igel M, Tribble DL, Shah S, et al. Inhibition of intestinal cholesterol absorption by ezetimibe in humans. Circulation. 2002;106(15):1943–1948. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034044.95911.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agellon LB, Drover VA, Cheema SK, Gbaguidi GF, Walsh A. Dietary cholesterol fails to stimulate the human cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene (CYP7A1) in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(23):20131–20134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costet P, Luo Y, Wang N, Tall AR. Sterol-dependent transactivation of the ABC1 promoter by the liver X receptor/retinoid X receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(36):28240–28245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy MA, Venkateswaran A, Tarr PT, Xenarios I, Kudoh J, Shimizu N, et al. Characterization of the human ABCG1 gene: liver X receptor activates an internal promoter that produces a novel transcript encoding an alternative form of the protein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(42):39438–39447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105863200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Repa JJ, Berge KE, Pomajzl C, Richardson JA, Hobbs H, Mangelsdorf DJ. Regulation of ATP-binding cassette sterol transporters ABCG5 and ABCG8 by the liver X receptors alpha and beta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(21):18793–18800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109927200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Repa JJ, Turley SD, Lobaccaro JA, Medina J, Li L, Lustig K, et al. Regulation of absorption and ABC1-mediated efflux of cholesterol by RXR heterodimers. Science. 2000;289(5484):1524–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz K, Lawn RM, Wade DP. ABC1 gene expression and ApoA-I-mediated cholesterol efflux are regulated by LXR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;274(3):794–802. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singaraja RR, Bocher V, James ER, Clee SM, Zhang LH, Leavitt BR, et al. Human ABCA1 BAC transgenic mice show increased high density lipoprotein cholesterol and ApoAI-dependent efflux stimulated by an internal promoter containing liver X receptor response elements in intron 1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(36):33969–33979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102503200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venkateswaran A, Repa JJ, Lobaccaro JM, Bronson A, Mangelsdorf DJ, Edwards PA. Human white/murine ABC8 mRNA levels are highly induced in lipid-loaded macrophages. A transcriptional role for specific oxysterols. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(19):14700–14707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu L, Gupta S, Xu F, Liverman AD, Moschetta A, Mangelsdorf DJ, et al. Expression of ABCG5 and ABCG8 is required for regulation of biliary cholesterol secretion. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(10):8742–8747. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411080200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Repa JJ, Liang G, Ou J, Bashmakov Y, Lobaccaro JM, Shimomura I, et al. Regulation of mouse sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c gene (SREBP-1c) by oxysterol receptors, LXRalpha and LXRbeta. Genes Dev. 2000;14(22):2819–2830. doi: 10.1101/gad.844900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao G, Liang Y, Broderick CL, Oldham BA, Beyer TP, Schmidt RJ, et al. Antidiabetic action of a liver x receptor agonist mediated by inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(2):1131–1136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grefhorst A, van Dijk TH, Hammer A, van der Sluijs FH, Havinga R, Havekes LM, et al. Differential effects of pharmacological liver X receptor activation on hepatic and peripheral insulin sensitivity in lean and ob/ob mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289(5):E829–838. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00165.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laffitte BA, Chao LC, Li J, Walczak R, Hummasti S, Joseph SB, et al. Activation of liver X receptor improves glucose tolerance through coordinate regulation of glucose metabolism in liver and adipose tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(9):5419–5424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830671100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grempler R, Gunther S, Steffensen KR, Nilsson M, Barthel A, Schmoll D, et al. Evidence for an indirect transcriptional regulation of glucose-6-phosphatase gene expression by liver X receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338(2):981–986. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herzog B, Hallberg M, Seth A, Woods A, White R, Parker MG. The nuclear receptor cofactor, receptor-interacting protein 140, is required for the regulation of hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism by liver X receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(11):2687–2697. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stulnig TM, Oppermann U, Steffensen KR, Schuster GU, Gustafsson JA. Liver X receptors downregulate 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 expression and activity. Diabetes. 2002;51(8):2426–2433. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.8.2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee MH, Lu K, Patel SB. Genetic basis of sitosterolemia. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2001;12(2):141–149. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200104000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kruit JK, Groen AK, van Berkel TJ, Kuipers F. Emerging roles of the intestine in control of cholesterol metabolism. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(40):6429–6439. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i40.6429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kruit JK, Plosch T, Havinga R, Boverhof R, Groot PH, Groen AK, et al. Increased fecal neutral sterol loss upon liver X receptor activation is independent of biliary sterol secretion in mice. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(1):147–156. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mulligan JD, Flowers MT, Tebon A, Bitgood JJ, Wellington C, Hayden MR, et al. ABCA1 is essential for efficient basolateral cholesterol efflux during the absorption of dietary cholesterol in chickens. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(15):13356–13366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murthy S, Born E, Mathur SN, Field FJ. LXR/RXR activation enhances basolateral efflux of cholesterol in CaCo-2 cells. J Lipid Res. 2002;43(7):1054–1064. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m100358-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brunham LR, Kruit JK, Pape TD, Parks JS, Kuipers F, Hayden MR. Tissue-specific induction of intestinal ABCA1 expression with a liver X receptor agonist raises plasma HDL cholesterol levels. Circ Res. 2006;99(7):672–674. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000244014.19589.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laffitte BA, Repa JJ, Joseph SB, Wilpitz DC, Kast HR, Mangelsdorf DJ, et al. LXRs control lipid-inducible expression of the apolipoprotein E gene in macrophages and adipocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(2):507–512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021488798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Joseph SB, McKilligin E, Pei L, Watson MA, Collins AR, Laffitte BA, et al. Synthetic LXR ligand inhibits the development of atherosclerosis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(11):7604–7609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112059299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levin N, Bischoff ED, Daige CL, Thomas D, Vu CT, Heyman RA, et al. Macrophage liver X receptor is required for antiatherogenic activity of LXR agonists. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(1):135–142. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000150044.84012.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terasaka N, Hiroshima A, Koieyama T, Ubukata N, Morikawa Y, Nakai D, et al. T-0901317, a synthetic liver X receptor ligand, inhibits development of atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. FEBS Lett. 2003;536(1–3):6–11. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kennedy MA, Barrera GC, Nakamura K, Baldan A, Tarr P, Fishbein MC, et al. ABCG1 has a critical role in mediating cholesterol efflux to HDL and preventing cellular lipid accumulation. Cell Metab. 2005;1(2):121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sabol SL, Brewer HB, Jr, Santamarina-Fojo S. The human ABCG1 gene: identification of LXR response elements that modulate expression in macrophages and liver. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(10):2151–2167. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500080-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Venkateswaran A, Laffitte BA, Joseph SB, Mak PA, Wilpitz DC, Edwards PA, et al. Control of cellular cholesterol efflux by the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXR alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(22):12097–12102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200367697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naik SU, Wang X, Da Silva JS, Jaye M, Macphee CH, Reilly MP, et al. Pharmacological activation of liver X receptors promotes reverse cholesterol transport in vivo. Circulation. 2006;113(1):90–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.560177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hansson GK, Robertson AK, Soderberg-Naucler C. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:297–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Castrillo A, Joseph SB, Vaidya SA, Haberland M, Fogelman AM, Cheng G, et al. Crosstalk between LXR and toll-like receptor signaling mediates bacterial and viral antagonism of cholesterol metabolism. Mol Cell. 2003;12(4):805–816. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00384-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Joseph SB, Castrillo A, Laffitte BA, Mangelsdorf DJ, Tontonoz P. Reciprocal regulation of inflammation and lipid metabolism by liver X receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9(2):213–219. doi: 10.1038/nm820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joseph SB, Bradley MN, Castrillo A, Bruhn KW, Mak PA, Pei L, et al. LXR-dependent gene expression is important for macrophage survival and the innate immune response. Cell. 2004;119(2):299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blaschke F, Leppanen O, Takata Y, Caglayan E, Liu J, Fishbein MC, et al. Liver X receptor agonists suppress vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and inhibit neointima formation in balloon-injured rat carotid arteries. Circ Res. 2004;95(12):e110–123. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000150368.56660.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Imayama I, Ichiki T, Patton D, Inanaga K, Miyazaki R, Ohtsubo H, et al. Liver X receptor activator downregulates angiotensin II type 1 receptor expression through dephosphorylation of Sp1. Hypertension. 2008;51(6):1631–1636. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.106963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cummins CL, Volle DH, Zhang Y, McDonald JG, Sion B, Lefrancois-Martinez AM, et al. Liver X receptors regulate adrenal cholesterol balance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1902–1912. doi: 10.1172/JCI28400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nilsson M, Stulnig TM, Lin CY, Yeo AL, Nowotny P, Liu ET, et al. Liver X receptors regulate adrenal steroidogenesis and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal feedback. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(1):126–137. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Steffensen KR, Neo SY, Stulnig TM, Vega VB, Rahman SS, Schuster GU, et al. Genome-wide expression profiling; a panel of mouse tissues discloses novel biological functions of liver X receptors in adrenals. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;33(3):609–622. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Robertson KM, Schuster GU, Steffensen KR, Hovatta O, Meaney S, Hultenby K, et al. The liver X receptor-{beta} is essential for maintaining cholesterol homeostasis in the testis. Endocrinology. 2005;146(6):2519–2530. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steffensen KR, Robertson K, Gustafsson JA, Andersen CY. Reduced fertility and inability of oocytes to resume meiosis in mice deficient of the Lxr genes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;256(1–2):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Volle DH, Mouzat K, Duggavathi R, Siddeek B, Dechelotte P, Sion B, et al. Multiple roles of the nuclear receptors for oxysterols liver X receptor to maintain male fertility. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(5):1014–1027. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gong H, Guo P, Zhai Y, Zhou J, Uppal H, Jarzynka MJ, et al. Estrogen deprivation and inhibition of breast cancer growth in vivo through activation of the orphan nuclear receptor liver X receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(8):1781–1790. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kolsch H, Lutjohann D, Ludwig M, Schulte A, Ptok U, Jessen F, et al. Polymorphism in the cholesterol 24S-hydroxylase gene is associated with Alzheimer's disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7(8):899–902. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lutjohann D, von Bergmann K. 24S-hydroxycholesterol: a marker of brain cholesterol metabolism. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36 (Suppl 2):S102–106. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-43053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liang Y, Lin S, Beyer TP, Zhang Y, Wu X, Bales KR, et al. A liver X receptor and retinoid X receptor heterodimer mediates apolipoprotein E expression, secretion and cholesterol homeostasis in astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2004;88(3):623–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sun Y, Yao J, Kim TW, Tall AR. Expression of liver X receptor target genes decreases cellular amyloid beta peptide secretion. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(30):27688–27694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Whitney KD, Watson MA, Collins JL, Benson WG, Stone TM, Numerick MJ, et al. Regulation of cholesterol homeostasis by the liver X receptors in the central nervous system. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16(6):1378–1385. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.6.0835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Burns MP, Vardanian L, Pajoohesh-Ganji A, Wang L, Cooper M, Harris DC, et al. The effects of ABCA1 on cholesterol efflux and Abeta levels in vitro and in vivo. J Neurochem. 2006;98(3):792–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Koldamova R, Staufenbiel M, Lefterov I. Lack of ABCA1 considerably decreases brain ApoE level and increases amyloid deposition in APP23 mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(52):43224–43235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504513200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zelcer N, Khanlou N, Clare R, Jiang Q, Reed-Geaghan EG, Landreth GE, et al. Attenuation of neuroinflammation and Alzheimer's disease pathology by liver x receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(25):10601–10606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701096104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Muscat GE, Wagner BL, Hou J, Tangirala RK, Bischoff ED, Rohde P, et al. Regulation of cholesterol homeostasis and lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle by liver X receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(43):40722–40728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Delvecchio CJ, Bilan P, Nair P, Capone JP. LXR-induced reverse cholesterol transport in human airway smooth muscle is mediated exclusively by ABCA1. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295(5):L949–957. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90394.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Delvecchio CJ, Bilan P, Radford K, Stephen J, Trigatti BL, Cox G, et al. Liver X receptor stimulates cholesterol efflux and inhibits expression of proinflammatory mediators in human airway smooth muscle cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(6):1324–1334. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Birrell MA, Catley MC, Hardaker E, Wong S, Willson TM, McCluskie K, et al. Novel role for the liver X nuclear receptor in the suppression of lung inflammatory responses. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(44):31882–31890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703278200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Birrell MA, De Alba J, Catley MC, Hardaker E, Wong S, Collins M, et al. Liver X receptor agonists increase airway reactivity in a model of asthma via increasing airway smooth muscle growth. J Immunol. 2008;181(6):4265–4271. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Morello F, de Boer RA, Steffensen KR, Gnecchi M, Chisholm JW, Boomsma F, et al. Liver X receptors alpha and beta regulate renin expression in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(7):1913–1922. doi: 10.1172/JCI24594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Proctor G, Jiang T, Iwahashi M, Wang Z, Li J, Levi M. Regulation of renal fatty acid and cholesterol metabolism, inflammation, and fibrosis in Akita and OVE26 mice with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55(9):2502–2509. doi: 10.2337/db05-0603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Groot PH, Pearce NJ, Yates JW, Stocker C, Sauermelch C, Doe CP, et al. Synthetic LXR agonists increase LDL in CETP species. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(10):2182–2191. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500116-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Luo Y, Tall AR. Sterol upregulation of human CETP expression in vitro and in transgenic mice by an LXR element. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(4):513–520. doi: 10.1172/JCI8573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Quinet EM, Savio DA, Halpern AR, Chen L, Miller CP, Nambi P. Gene-selective modulation by a synthetic oxysterol ligand of the liver X receptor. J Lipid Res. 2004;45(10):1929–1942. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400257-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kratzer A, Buchebner M, Pfeifer T, Becker TM, Uray G, Miyazaki M, et al. Synthetic LXR agonist attenuates plaque formation in apoE-deficient mice without inducing liver steatosis and hypertriglyceridemia. J Lipid Res. 2008 doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800376-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hu B, Quinet E, Unwalla R, Collini M, Jetter J, Dooley R, et al. Carboxylic acid based quinolines as liver X receptor modulators that have LXRbeta receptor binding selectivity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18(1):54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lund EG, Peterson LB, Adams AD, Lam MH, Burton CA, Chin J, et al. Different roles of liver X receptor alpha and beta in lipid metabolism: effects of an alpha-selective and a dual agonist in mice deficient in each subtype. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71(4):453–463. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Quinet EM, Savio DA, Halpern AR, Chen L, Schuster GU, Gustafsson JA, et al. Liver X receptor (LXR)-beta regulation in LXRalpha-deficient mice: implications for therapeutic targeting. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70(4):1340–1349. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.022608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bradley MN, Hong C, Chen M, Joseph SB, Wilpitz DC, Wang X, et al. Ligand activation of LXR beta reverses atherosclerosis and cellular cholesterol overload in mice lacking LXR alpha and apoE. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(8):2337–2346. doi: 10.1172/JCI31909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Beyea MM, Heslop CL, Sawyez CG, Edwards JY, Markle JG, Hegele RA, et al. Selective up-regulation of LXR-regulated genes ABCA1, ABCG1, and APOE in macrophages through increased endogenous synthesis of 24(S),25-epoxycholesterol. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(8):5207–5216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]