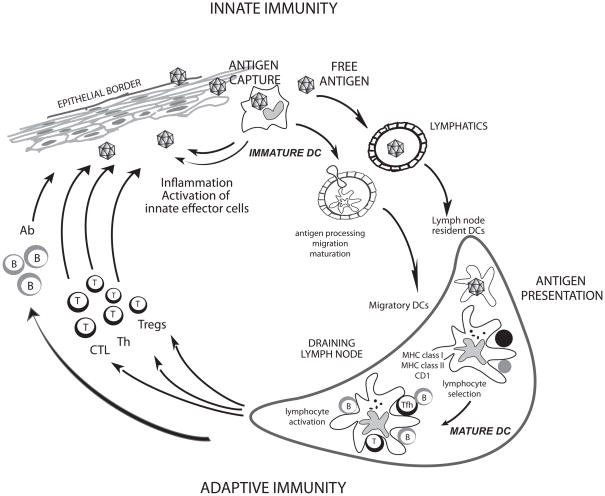

Figure 1. Dendritic cells.

DCs reside in the tissue where they are poised to capture antigens (Geissmann et al. 2010). During inflammation, circulating precursor DC enter tissues as immature DC (Geissmann et al. 2010). DCs can encounter pathogens (e.g.: viruses) directly, which induce secretion of cytokines (e.g.: IFN-α); or indirectly through the pathogen effect on stromal cells. Cytokines secreted by DCs in turn activate effector cells of innate immunity such as eosinophils, macrophages and NK cells. Microbe activation triggers DCs migration towards secondary lymphoid organs and simultaneous activation (maturation). These activated migratory DCs that enter lymphoid organs display antigens in the context of classical MHC class I and class II or non-classical CD1 molecules, which allow selection of rare circulating antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Activated T cells help drive DCs toward their terminal maturation, which allows lymphocyte expansion and differentiation. Activated T lymphocytes traverse inflamed epithelia and reach the injured tissue, where they eliminate microbes and/or microbe-infected cells. B cells, activated by DCs and T cells, migrate into various areas where they mature into plasma cells that produce antibodies that neutralize the initial pathogen. Antigen can also reach draining lymph nodes without involvement of peripheral tissue DCs and be captured and presented by lymph node resident DCs (Itano et al. 2003).