Abstract

Background

Partial hand amputations for malignant tumors allow tumor resection with negative resection margins, which is associated with lower local recurrence rates and improved overall survival while preserving native tissue, which improves functional outcome.

Questions/purposes

We conducted this study to assess the functional outcome of double ray amputations of the hand.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the records of five patients who underwent double ray amputations at our center over 12 years: four amputations of the fourth and fifth rays and one amputation of the second and third rays. Mean age at surgery was 34 years (range, 10–45 years), and minimum followup was 64 months (mean, 98 months; range, 64–136 months). All five patients had high-grade soft tissue sarcomas of the hand, two synovial sarcomas, two malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, and one undifferentiated sarcoma. No patients had detectable metastases at surgery.

Results

Four of the five patients were completely disease-free at latest followup. One patient was alive with lung metastases detected 32 months after surgery. No patients developed local tumor recurrence. Functional assessment showed a mean Musculoskeletal Tumor Society score of 24 (range, 19–28) and mean grip strength 24% of the contralateral side (range, 17%–35%).

Conclusions

Although double ray amputation results in worse functional outcome than single ray, good key, tip, and tripod pinch can be preserved when the deep motor branch of the ulnar nerve is preserved, and this hand can still assist in bimanual hand activities. Our observations suggest double ray amputation is an acceptable hand-preserving procedure.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Hand amputations cause substantial functional loss for patients [1, 6]. Whether performed for infection, trauma, or tumors, surgeons should attempt to preserve or reconstruct at least part of the hand so it may assist the contralateral limb for bimanual activities. In patients with malignant tumors of the extremities, the decision about the extent of resection requires a balance between the requirement for negative resection margins, which is associated with reduced local recurrence and improved overall survival, and the functional requirement for greater preservation of native tissue, which improves functional outcome. This difficult decision is even more challenging within the limited anatomic confines of the hand.

Partial hand amputations offer a compromise between these two competing requirements. Single ray amputation for tumors of the hand can give low local recurrence rates and good overall survival, as well as functional outcomes almost comparable to ray amputations performed for trauma [9]. However, more extensive resections may be required for larger tumors. One case report of a patient with clear cell sarcoma who had undergone a triple ray amputation showed recurrence-free survival at 3 years postoperatively as well as preservation of digit opposition and pinch [7]. However, apart from that one case, the range of function of more extensive partial hand amputation compared to single ray amputation is unclear.

We conducted this review to assess the following for double ray amputation when performed for malignant tumors: (1) the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) score and hand grip strength; and (2) the local recurrence rate and survival for patients who underwent hand-preserving resections with double ray amputations for malignant tumors of the hand.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all patients with malignant tumors of the hand who were treated surgically between 1995 and 2007. Five patients who had undergone double ray amputations during this period, including two male and three female patients, were identified. The mean age at surgery was 34 years (range, 10–45 years) (Table 1). All five patients had high-grade soft tissue sarcomas of the hand, two synovial sarcomas, two malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, and one undifferentiated sarcoma. None of the patients had detectable metastases at the time of surgery. Four patients underwent a double ray amputation of the fourth and fifth rays, and the final patient had an amputation of the second and third rays. The nondominant hand was affected in all patients (four left, one right). The minimum followup was 64 months (mean, 94 months; range, 64–136 months).

Table 1.

Patient summary

| Patient number | Age (years) | Gender | Diagnosis | Presentation | Grade | Affected hand | Dominant hand | Tumor size (cm) | AJCC stage | Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45 | M | Synovial sarcoma | Primary | High | Left | Right | 2 | 2b | Double fourth and fifth ray amputation |

| 2 | 35 | F | MPNST | Primary | High | Right | Left | 4.5 | 2b | Double fourth and fifth ray amputation |

| 3 | 40 | M | Synovial sarcoma | Primary | High | Left | Right | 6.5 | 3 | Double fourth and fifth ray amputation |

| 4 | 10 | F | MPNST | Primary | High | Left | Right | 5 | 3 | Double second and third ray amputation |

| 5 | 40 | F | Undifferentiated sarcoma | Primary | High | Left | Right | 5 | 3 | Double fourth and fifth ray amputation |

| Patient number | Margins | Radiation | Flap closure | Local recurrence | Distant metastases | Followup (months) | Status | MSTS score | Grip strength (% contralateral) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Negative | No | No | No | No | 98 | NED | 26 | 24 |

| 2 | Negative | Yes | Fillet flap | No | Yes | 64 | AWD (lung metastases) | 28 | 17 |

| 3 | Negative | Yes | Free gracilis myocutaneous flap | No | No | 120 | NED | 19 | 18 |

| 4 | Negative | Yes | No | No | No | 72 | NED | 24 | 35 |

| 5 | Negative | Yes | No | No | No | 136 | NED | 23 | NA |

AJCC = American Joint Commission for Cancer; M = male; F = female; MPNST = malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors; MSTS = Musculoskeletal Tumor Society; NED = no evidence of disease; AWD = alive with disease; NA = not available.

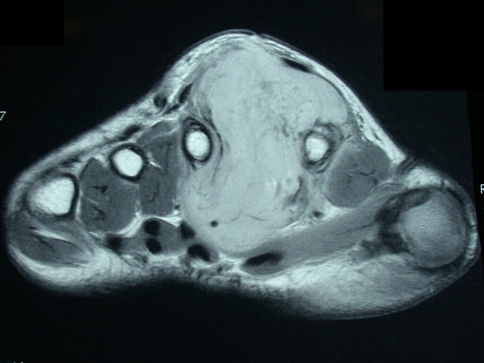

We performed double ray amputations for those patients with malignant lesions of the hand shown on MRI to involve the metacarpal of two adjacent rays and/or both neurovascular bundles of the two digits (Fig. 1). If one neurovascular bundle of a ray could be preserved, we opted for a single ray amputation with reconstruction of the sacrificed nerve and/or tendon where necessary.

Fig. 1.

This MRI scan shows a large malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor occupying the second interosseous space between the second and third rays for Patient 2.

Tumor excision was performed through volar Z-Brunner-type incisions and dorsal incisions that incorporated the previous biopsy incision (Fig. 2). A fillet flap was raised from one of the amputated rays based on the volar digital arteries in one patient. The extensor mechanism was then incised proximally and the interosseous muscles incised with the periosteum of the adjacent digit taken as a surgical margin. The volar incisions were made and developed and the neurovascular bundles identified. One digital neurovascular bundle to an adjacent digit that was not amputated was sacrificed in two patients as well as the deep motor branch of the ulnar nerve in one patient to completely excise the tumor. The bone was then cut through the base of the metacarpal or the ray disarticulated through the carpometacarpal joint (Fig. 3). The skin flaps were then fashioned and the wound closed (Fig. 4). Flaps were required for wound closure for two patients, one of whom required a free myocutaneous gracilis flap and the other a pedicled fillet flap of the finger. Special areas of concern include the ulnar nerve and artery as they wind around the hook of hamate, the radial artery as it winds around the base of the second metacarpal, and the deep motor branch of the ulnar nerve during osteotomy at the base of the central rays.

Fig. 2.

This photograph depicts the marking of the incision incorporating the previous biopsy track.

Fig. 3.

This photograph depicts a resection specimen.

Fig. 4.

This photograph depicts the hand after wound closure.

Patients stayed overnight in the hospital and were discharged the day after surgery except for the patient who required the free flap, who stayed 5 days. ROM therapy was initiated by the surgeon while the patient was still in the hospital. Patients were reviewed on the tenth postoperative day when stitches were removed. Hand rehabilitation continued under the supervision of a hand occupational therapist.

We managed to achieve negative resection margins for all patients. External beam radiotherapy was given to 4 out of 5 patients (Patients 2–5) because of either large tumor size (Patients 3–5) or a close resection margin (Patient 2). Given the final histology of the tumors, none of the patients received chemotherapy.

Patients were then reviewed at 6 weeks, at 3 months, and then every 3 months during the first year, every 4 months for the next 2 years, and every 6 months during the fourth and fifth years. Using the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) score [5], we assessed hand function when we believed it had stabilized, on average 6 months after surgery. Grip strength was also measured at this time using a Baseline® Hydraulic Hand Dynamometer (Fabrication Enterprises, Inc, Irvington, NY). This was recorded for 4 of the 5 patients in this study. Local recurrence was assessed clinically during each clinic visit. An MRI scan of the hand would be obtained if a suspicious nodule was detected and this would be followed by a biopsy to prove or disprove a local recurrence. Chest radiographs were taken at these visits and CT scans of the chest performed yearly to look for lung metastases. We did not routinely use any other modalities such as PET or bone scans to look for extra pulmonary sites of distant metastases unless there was a reason to suspect it clinically.

Results

Functional assessment showed a mean MSTS score of 24 (range, 19–28). We measured the grip strength in four patients with a mean of 24% (range, 17%–35%) of the contralateral side. Grip strength was not recorded for one patient (Patient 5).

Four patients are completely disease-free. One patient is alive with lung metastases that were detected 32 months after surgery. None of the patients developed local recurrence of the tumor.

Discussion

We conducted this review to assess the following: (1) the functional outcome, measured using MSTS score and hand grip strength; and (2) the local recurrence rate and survival for patients who had undergone hand-preserving resections with double ray amputations for malignant tumors of the hand.

Our study is first limited by its small size, which we could not avoid given the uncommon indications for this procedure. While no patient had local recurrence and one developed distant metastases, we are unsure these findings can be generalized given the small patient number. Second, we lacked a detailed analysis of hand function with tip and key pinch assessment but these were not obtained and some of the patients were lost to followup and could not be recalled.

Hand preservation is possible in most patients with malignant tumors of the hand [2–4, 8], although the type of resection selected—whether en bloc soft tissue resections without digit sacrifice or partial hand amputation—depends to a great degree on the size and location of the tumor. The functional and aesthetic outcomes after partial hand amputations depend on the extent of resection. Patients with double ray amputations have lower MSTS scores (24 versus 27.5) and hand grip strength (24% versus 66% of contralateral side) than do patients with single ray amputations in the oncology setting [9]. Despite this, good key, tip, and tripod pinch can be preserved when the deep motor branch of the ulnar nerve is preserved, and the hand can still be used to assist in bimanual hand activities, resulting in a better functional outcome than complete hand amputation.

Our observations suggest double ray amputation is an acceptable hand-preserving procedure, although it has poorer aesthetic and functional outcomes than single ray amputation [9].

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his institution has approved the reporting of this study and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

References

- 1.Beasley RW. Surgery of hand and finger amputations. Orthop Clin North Am. 1981;12:763–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray PW, Bell RS, Bowen CV, Davis A, O’Sullivan B. Limb salvage surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy for soft tissue sarcomas of the forearm and hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22:495–503. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(97)80019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brien EW, Terek RM, Geer RJ, Caldwell G, Brennan MF, Healey JH. Treatment of soft-tissue sarcomas of the hand. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:564–571. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199504000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buecker PJ, Villafuerte JE, Hornicek FJ, Gebhardt MC, Mankin HJ. Improved survival for sarcomas of the wrist and hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:452–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enneking WF, Dunham W, Gebhardt MC, Malawar M, Pritchard DJ. A system for the functional evaluation of reconstructive procedures after surgical treatment of tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;286:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grob M, Papadopulos NA, Zimmermann A, Biemer E, Kovacs L. The psychological impact of severe hand injury. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2008;33:358–362. doi: 10.1177/1753193407087026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller SJ, Rayan GM. Triple central ray amputation for clear cell sarcoma of the hand. Am J Orthop. 2000;29:226–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pradhan A, Cheung YC, Grimer RJ, Peake D, Al-Muderis OA, Thomas JM, Smith M. Soft-tissue sarcomas of the hand: oncological outcome and prognostic factors. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:209–214. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B2.19601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puhaindran ME, Healey JH, Athanasian EA. Single ray amputation for tumors of the hand. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009 Aug 5 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]