Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

In September 2005, the Alberta government introduced the daily physical activity (DPA) initiative, which requires that students from grades 1 to 9 be physically active in school for a minimum of 30 min per day.

OBJECTIVE:

To obtain information on whether and how the DPA initiative has been implemented in Calgary schools.

METHODS:

Information was obtained through a descriptive survey. Principals and vice-principals from elementary schools participated in an interview, in which they were asked questions about the DPA initiative, their definition of physical activity, the types of activities that fulfilled the DPA requirement, and barriers to increasing physical activity and physical education.

RESULTS:

98.2% of respondents reported being aware of the DPA initiative; 100% of respondents reported it being successfully implemented. The leading responses to the question, “How do you define physical activity?” were “moving/movement” (43.5%), “increasing the heart rate” (32.7%) and “being active” (29%). 78.2% of participants responded that physical education was the only type of activity that fulfilled the DPA requirement; the other participants reported that recess, intramurals and DPA periods organized by the teacher also counted. 69.1% and 61.1% of respondents, respectively, stated that there were barriers to increasing physical education and physical activity. A lack of time in the curriculum, a lack of space and a lack of funding were the most frequently reported barriers.

CONCLUSION:

According to principal and vice-principal reports, the DPA initiative has been successfully implemented in elementary schools in Calgary. This suggests that government initiatives directed at increasing physical activity at school could result in increasing the actual amount of physical activity that children participate in. However, prospective longitudinal research directly measuring the amount of physical activity that children engage in is needed to directly assess the impact of such initiatives.

Keywords: Elementary schools, Physical activity, Physical education

Abstract

INTRODUCTION :

En septembre 2005, le gouvernement de l’Alberta a lancé la Daily Physical Activity (DPA, ou initiative d’activité physique quotidienne), selon laquelle les élèves de 1re à 9e année doivent faire de l’activité physique au moins 30 minutes par jour dans leur école.

OBJECTIF :

Obtenir de l’information pour déterminer si l’initiative de DPA a été implantée dans les écoles de Calgary et la manière dont elle l’a été.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont obtenu l’information au moyen d’un sondage descriptif. Les directeurs et les directeurs adjoints des écoles primaires ont participé à une entrevue, au cours de laquelle ont leur a posé des questions sur l’initiative de DPA, leur définition de l’activité physique, le type d’activités qui respectaient les critères de DPA et les obstacles à l’augmentation de l’activité physique et des cours d’éducation physique.

RÉSULTATS :

Environ 98,2 % des participants ont déclaré être au courant de l’initiative de DPA; 100 % des participants ont affirmé qu’elle était bien implantée. La principale réponse à la question « Comment définissez-vous l’activité physique? » était « bouger/mouvement » (43, 5 %), « accroître le rythme cardiaque » (32,7 %) et « être actif » (29 %). 78,2 % des participants ont répondu que l’éducation physique était le seul type d’activité qui respectait les exigences de DPA. Pour les autres participants, les récréations, les activités intra-muros et les périodes de DPA organisées par les enseignants comptaient aussi. 69,1 % et 61,1 % des participants ont affirmé qu’il y avait des obstacles à l’augmentation de l’éducation physique et de l’activité physique, respectivement. Les plus cités étaient un manque de temps dans le programme, un manque d’espace et un manque de financement.

CONCLUSION:

D’après le rapport des directeurs, l’initiative de DPA a été implantée avec succès dans les écoles primaires de Calgary. D’après ces résultats, les initiatives gouvernementales visant à accroître l’activité physique à l’école pourraient susciter une augmentation de la quantité réelle d’activité physique à laquelle s’adonnent les enfants. Cependant, il faut mener des recherches prospectives longitudinales mesurant la quantité d’activité physique à laquelle participent les enfants pour évaluer directement les répercussions de telles initiatives.

The prevalence of overweight/obesity among children of all ages has reached epidemic proportions (1,2). Because it is challenging to reverse obesity in the pediatric population, prevention should be encouraged. Suggested interventions include reducing sedentary behaviour and increasing energy expenditure (2). Schools have the potential to help children develop lifelong, healthy eating patterns and encourage physical activity; research supports school-based interventions to increase physical activity and decrease obesity (3–6). Health Canada suggests that children and youth between six and 14 years of age participate in 60 min of moderate and 30 min of vigorous activity daily, but has not yet made a recommendation as to how much of this activity should take place during school hours. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no Canadian studies have examined how much daily physical activity (DPA) children are participating in at school.

In September 2005, the Alberta government introduced the Alberta DPA initiative. This initiative requires that all students in grades 1 to 9 be physically active for a minimum of 30 min a day at school through activities that are organized by the school. To assess the impact of this government initiative, it is necessary that research examine whether and how this initiative has been implemented in schools. To determine how this initiative has been implemented, it is essential that information be obtained on the activities schools identify as contributing to children’s physical activity. The purpose of the present study was to obtain information on whether and how the DPA initiative has been implemented in elementary schools in Calgary, Alberta. Based on the reports of principals and vice-principals, information was obtained on the proportion of elementary schools in Calgary that reported knowledge regarding the DPA initiative’s requirement. The proportion of schools that reported adhering to the DPA initiative’s requirement of 30 min of DPA was also examined. Furthermore, information was obtained on how physical activity was defined, as well as the types of physical activities that were viewed as fulfilling the DPA requirement. Finally, information on barriers to increasing physical activity and physical education in schools was obtained.

METHODS

The information was obtained through a descriptive survey. Participants were randomly selected and included principals and vice-principals from public, private and charter elementary schools in Calgary. All schools that offered any of grades 1 through 6 (ie, children approximately five to 12 years of age) were eligible to participate in the study. Schools that offered only special needs or home schooling programs were excluded. Permission was obtained from the Calgary Board of Education (CBE) to randomly sample schools within the CBE. The CBE is one of the largest school boards in Canada and has 153 elementary schools with an enrollment of over 42,000 elementary students. Calgary private and charter schools also participated in the study. At the time of the study, there were 41 private and 13 charter schools in Calgary. A random sample of these schools was approached individually and asked to participate. The Calgary Catholic School District, which has an enrollment of approximately 20,000 students in grades 1 through 6, declined the request to participate. The protocol was approved by the local institutional review board for the ethics of human research.

Burgeson et al (7) reported that among American schools, 81.4% follow national, state or district physical education standards or guidelines. Using this information, it was predicted that 81% of Calgary elementary schools would follow the Alberta DPA initiative’s guideline. With a 95% CI width of ±10%, it was estimated that 47 schools would be needed. Assuming a 31% nonresponse rate (ie, 47×0.31=15), 62 schools were randomly selected from the 207 public, private and charter schools. (A nonresponse rate of 31% was reported by Burgeson et al [7] in the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2000.) The principals or vice-principals of these schools were reached by telephone and were asked to participate.

A total of 55 of 62 (88.7%) schools participated in the study. Participants could choose to be interviewed over the telephone or to complete an electronic version of the survey and return it to the investigators. Forty-nine participants elected to be interviewed, and six completed electronic surveys. Of the seven schools that did not participate, four requested an electronic survey, but did not return it; at three of the schools, the principal/vice-principal could not be reached by telephone (five attempts were made to contact the principal/vice-principal). Principals comprised 94.5% of the respondents; vice-principals made up the remaining 5.5%. The schools surveyed came from all four quadrants in Calgary (19.4% from the northwest, 19.4% from the northeast, 32.3% from the southwest and 29% from the southeast).

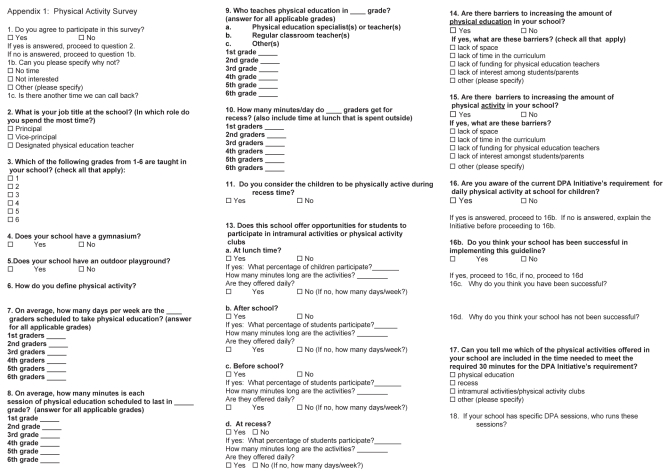

The survey (Appendix 1) was developed by the investigators and was pretested for its clarity and face validity with a CBE curriculum specialist in physical and outdoor education, before being administered. Inter-rater reliability was assessed by randomly selecting some of the schools that were initially surveyed and readministering the survey to either the physical education teacher or a classroom teacher who instructed physical education. Twenty schools were contacted. From these, nine teachers were contacted by telephone, seven of whom agreed to participate and two of whom declined. The seven teachers were all physical education specialists.

RESULTS

98.2% of the principals and vice-principals reported being aware of the DPA initiative. One principal reported that she was not aware of the initiative. She was a new principal who had recently moved to Calgary from the United States; the investigator, therefore, described the initiative to her. All of the participants stated that their school had been successful in implementing the DPA initiative’s requirement. The responses provided regarding the principals’ and vice-principals’ definitions of physical activity are presented Table 1. Physical education, recess, DPA periods and intramural activities were all mentioned as activities that were considered as types of physical activity. 78.2% of the participants stated that physical education time was the only type of activity that they considered as fulfilling the DPA requirement (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

How principals define physical activity

| Categories* | Percentage of principals who gave this response |

|---|---|

| Includes “moving/movement” | 43.5 |

| Involves “increasing the heart rate” | 32.7 |

| Includes “being active” | 29.0 |

| Involves “physical education class” | 16.2 |

| Includes “playing sports” | 9.0 |

| Includes “developing cardiovascular endurance/strength/flexibility” | 9.0 |

| Includes “organized activity” | 3.6 |

| Includes “body working hard/exerting itself” | 3.6 |

The participant responses were categorized by the investigators after reading through the participant responses. Participants were allowed to give more than one answer. Responses were not included in the table if fewer than 2% of participants gave that response

TABLE 2.

Activities viewed as fulfilling the daily physical activity initiative requirement

| Activity | Percentage of principals who gave this response |

|---|---|

| Physical education | 78.2 |

| Physical education and other* | 7.3 |

| Other* | 5.5 |

| Physical education and recess | 5.5 |

| Physical education, recess and other* | 1.8 |

| Physical education, intramurals and other* | 1.8 |

Other includes a 30 min daily physical activity period (activities within the classroom or outside that are organized by the classroom teacher)

Eighty per cent of schools provided daily physical education for all grades in their school. The average number of minutes per day of physical education was approximately 30. 94.5% of schools provided recess daily, and the average number of minutes per day was approximately 42 (Table 3). When participants were asked whether they considered the students to be physically active at recess, 77.4% of principals and vice-principals responded ‘yes’ and 22.6% responded ‘no’.

TABLE 3.

Number of minutes per day of physical education and recess

| Mean number of minutes/day of physical education | Schools that have daily physical education, % | Mean number of minutes/day of recess | Schools that have daily recess, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 30.7 | 80.0 | 42.3 | 94.5 |

| Grade 1 | 29.9 | 82.0 | 42.5 | 96.0 |

| Grade 2 | 29.9 | 82.0 | 42.5 | 96.0 |

| Grade 3 | 29.9 | 82.0 | 42.5 | 96.0 |

| Grade 4 | 29.4 | 78.0 | 42.5 | 96.0 |

| Grade 5 | 31.9 | 76.6 | 42.7 | 95.7 |

| Grade 6 | 33.2 | 76.6 | 41.0 | 93.5 |

All participants were asked whether their school offered intramural activities. 67.3% of schools offered intramurals at some time during the day, at some point in the year. Of the schools that offered intramurals, 50.9% offered them at lunch, 38.2% offered them before school, 14.5% offered them after school and 3.6% offered them at recess. The duration of the intramural activities ranged from 15 min to 55 min depending on the time of day that they were offered.

Principals and vice-principals were asked, “Why do you think your school has been successful in implementing the DPA initiative?” The answers are summarized in Table 4. Participants were also asked who instructed physical education classes. Overall, only 47.3% of schools had a physical education teacher on staff. In those schools with a physical education teacher, the teacher was more likely to teach physical education at higher grade levels.

TABLE 4.

Principals’ stated reasons for being successful in implementing the daily physical activity initiative

| Reason for success | Percentage of principals who gave this response |

|---|---|

| Already had daily physical education | 28.8 |

| Already met the guideline/requirement | 14.4 |

| Rearranged the time table to offer daily physical activity and/or daily physical education | 14.4 |

| Have adequate space in the school | 10.8 |

| Doubled up classes in the gym at one time | 9.0 |

| Added in extra programs/activities | 9.0 |

| Have made it a priority | 5.4 |

| Have teachers who believe in the importance of daily physical activity | 3.6 |

| It was mandatory, so we had to implement it | 3.6 |

| Have a physical education specialist in the school | 3.6 |

| Now use an outside facility or go outdoors to increase the space available to offer daily physical activity | 3.6 |

The responses were categorized by the investigators after reading through the participant responses. Participants were allowed to give more than one answer. Responses were not included if fewer than 2% of participants gave that response

69.1% of participants stated that there were barriers to increasing physical education and 61.1% stated that there were barriers to increasing physical activity in their schools. The specific barriers identified are summarized in Table 5.

TABLE 5.

Specific barriers identified by the principals who responded that there are barriers to increasing time for physical education and physical activity

| Barriers | Barriers to increasing time for physical education, % | Barriers to increasing time for physical activity, % |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of space | 50.0 | 38.7 |

| Lack of time in the curriculum | 68.4 | 54.8 |

| Lack of funding for a physical education teacher | 47.4 | 12.9 |

| Lack of student or parent interest | 2.6 | 6.5 |

| Other* | 15.8 | 64.5 |

The survey contained preset answers and an ‘other’ category; participants were allowed to give more than one answer.

Other barriers to increasing time for physical education included the following responses: lack of funding for equipment; challenging to get insurance to take kids to an outside facility for physical education; parents complain that the kids will be too tired if physical education time is increased and have to choose between hiring a music teacher or a physical education teacher. Other barriers to increasing time for physical activity included the following responses: unable to offer before or after school activities to bused students; don’t have staff to run before and after school activities; lack of funding to purchase equipment; physical activity is not culturally accepted; unable to offer after school activities in the winter because it gets dark early; it is a challenge to properly educate teachers on what quality daily physical activity is; temperature is too cold in the winter to get the children outside; children have other activities planned after school; hard to get kids to get up early to come for before school activities; parental attitudes – can’t even get parents to drop their kids off one block away to walk an extra block and families aren’t promoting physical activity

Reliability analysis

Of the seven physical education teachers who participated, one was unaware of the DPA initiative; all of the principals from the corresponding schools were aware. All seven teachers stated that the school had been successful in implementing the DPA initiative; therefore, there was 100% agreement between physical education teachers and principals. The physical education teachers’ responses regarding their definitions of physical activity were consistent with those given by principals and vice-principals and included “increasing the heart rate”, “moving/movement” and “daily physical education class”. However, there were differences between principals’ and physical education teachers’ responses to the question, “Do you consider the children to be active at recess?” Only two of seven physical education teachers thought that the children were active at recess compared with five of seven principals from the corresponding schools.

Compared with the principals and vice-principals, the physical education teachers gave similar responses to the question, “Why do you think your school was successful in implementing the DPA initiative?” The responses from the teachers included “already had daily physical education”, “already met the guideline”, “made it a priority”, “have adequate space”, “have teachers who believe in the importance of daily physical activity”, “have the time in the curriculum to offer DPA” and “parents have been supportive”.

When asked how many minutes per day the children have to participate in physical education and recess, the teachers’ responses were consistent with those of the principals and vice-principals. Three of the physical education teachers stated that there were barriers to increasing the amount of time for physical education. The barriers included a lack of time in the curriculum and a lack of staff. Three of the teachers stated that there were barriers to increasing the amount of time for physical activity. The barriers included a lack of space, a lack of equipment, a lack of staff and the fact that students are bused.

DISCUSSION

The Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute (8) reports that over one-half of Canadian children and youth five to 17 years of age, are not active enough for healthy growth and development. The Active Healthy Kids Canada 2009 Report Card (9) highlights that 87% of children and youth are not meeting Canada’s physical activity guideline of 90 min of physical activity per day. A recent study (10) conducted in the United States, involving children between nine and 13 years of age, reported that 61.5% did not participate in any organized physical activity and 22.6% did not partake in any free-time physical activities during nonschool hours. Given that inactivity is highly prevalent in school-aged children (8,10), the finding that the DPA initiative has been successfully implemented in all of the elementary schools surveyed in Calgary, provides evidence that government-sponsored school-based initiatives may be one means of increasing the physical activity level of school aged children. Support for the success of such initiatives can also be found in the Annual Report on Ontario’s Schools 2008 (11). According to this report, 98% of Ontario schools had implemented the DPA policy that elementary schools must offer 20 min per day, during instructional time, of moderate to vigorous physical activity, on top of the time that children get for physical education.

Although schools in Calgary can not be directly compared with schools in other jurisdictions, Calgary schools certainly surpass those in other parts of Canada, as well as schools in the United States, in regards to daily physical education according to the Canadian Association for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance (12), and the 2006 School Health Policies and Programs study (13). Eighty per cent of Calgary schools offered daily physical education; whereas across Canada, only 20% of children received daily physical education in school (12). Lee et al (13) reported that only 3.8% of elementary schools in the United States provided daily physical education for students in all grades, and 30.7% of elementary schools did not even require physical education in the curriculum. It is also of note that Calgary elementary school children were more likely to have recess compared with children in elementary schools in the United States. 94.5% of Calgary elementary schools offered daily recess for all grades in the school, whereas only 74% of American elementary schools provided regularly scheduled recess for all grades (13). Given the fact that more than 30 collaborating organizations, including the Canadian Paediatric Society and the American Academy of Pediatrics, recommend daily physical education and physical activity from kindergarten through grade 12 (13,14), it seems imperative that schools provide this to their students.

The barriers identified to increasing time for both physical education and physical activity (ie, lack of time in the curriculum, a lack of space and a lack of funding for physical education specialists) were similar to those reported in The Annual Report on Ontario’s Schools (ie, difficult to fit the time into the school day, hard to find adequate space, staff lack the training to offer DPA and a lack of resources to purchase equipment) (11). Addressing these barriers could result in increasing the amount of physical activity children engage in at school; however, schools would need monetary support to achieve this. For example, a lack of time in the curriculum could be overcome by offering more intramurals outside of regular school hours; however, schools do not have the funding to hire supervisors outside of school hours. Some schools have overcome the space barrier by using outside facilities to offer more physical education and physical activities; however, this option requires that the school has the financial resources to cover the cost of the rental fee.

To improve the outcomes of school-based physical activity initiatives, areas of service provision, such as teacher training and curriculum development, need be addressed. A study by Nader (15) found that children taught by classroom teachers spent a greater proportion of class time standing and walking than children who were taught by physical education specialists. McKenzie et al (16) reported that having a standardized physical education curriculum along with staff development resulted in students engaging in more moderate to vigorous physical activity in existing physical education classes. The Canadian Paediatric Society recommends that daily physical education classes be taught by qualified, trained educators (14). Unfortunately, only 47% of the Calgary elementary schools that participated in the present study had a physical education specialist, although this is superior to the rest of the country. Across Canada, 39% of schools report having a physical education specialist (17), whereas in Ontario, 44% of elementary schools have a physical education specialist (11). In the United States, 85.7% of elementary physical education classes had a teacher who was licensed to teach physical education at the elementary school level, although the number of schools with a physical education teacher was not reported (13). Providing designated funding for physical education specialists may assist in increasing the quality of the physical education classes and the actual amount of physical activity that the children engage in.

An area that we did not examine in the present study was whether children had access to game equipment during recess. It has been shown that providing equipment at recess is effective in increasing children’s physical activity levels (18). Given that the schools in our study had approximately 40 min/day of recess (depending on the individual grade), ensuring that children have access to game equipment that promotes physical activity is one way by which schools could increase the physical activity levels of their students.

The main limitation of our study was that we did not directly measure the physical activity that students were involved in; instead, we relied on principals’, vice-principals’ and physical education teachers’ reports, which may not accurately reflect the actual amount of physical activity in which the students participated.

Although schools can help children attain some of the recommended DPA time needed for healthy growth and development, schools should not be expected to be the sole source of physical activity for children. Even with DPA, children in Calgary schools did not attain enough minutes of physical activity during a school day to meet the Health Canada guidelines of 60 min of moderate activity and 30 min of vigorous activity daily. It is, therefore, important for schools to continue to work with children and their parents, as well as the community at large to promote physical activity as part of a healthy lifestyle.

CONCLUSION

Based on the reports of principals and vice-principals, the DPA initiative has been successfully implemented in elementary schools in Calgary. This suggests that government initiatives directed at increasing physical activity at school could result in increasing the amount of physical activity that children actually participate in at school. However, prospective, longitudinal research that directly measures the actual amount of physical activity engaged in by children at school is needed to directly assess the impact of such initiatives.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS/FUNDING

The authors thank the following people: Susan Crawford for her assistance with data analysis, Debra Busic for her assistance with data entry, Tom Parker (Curriculum Specialist with the CBE), and all the principals, vice-principals and physical education teachers who participated in the study. The present work originated from the University of Calgary, and is supported by a grant from the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation.

Appendix 1: Physical Activity Survey

REFERENCES

- 1.Troiano RP, Flegal KM. Overweight children and adolescents: Description, epidemiology, and demographics. Pediatrics. 1998;101:497–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCambridge TM, Bernhardt DT, Brenner JS, et al. Active healthy living: Prevention of childhood obesity through increased physical activity. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1834–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Summerbell CD, Waters E, Edmunds LD, Kelly S, Brown T, Campbell KJ. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3(3):CD001871. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein LH, Goldfield GS. Physical activity in the treatment of childhood overweight and obesity: Current evidence and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(11 Suppl):S553–9. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199911001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Datar A, Sturm R. Physical education in elementary school and body mass index: Evidence from the early childhood longitudinal study. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1501–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veugelers PJ, Fitzgerald AL. Prevalence of and risk factors for childhood overweight and obesity. CMAJ. 2005;173:607–13. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgeson CR, Wechsler H, Brener ND, Young JC, Spain CG. Physical education and activity: Results from the school health policies and programs study 2000. J Sch Health. 2001;71:279–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2001.tb03505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute 2000 physical activity monitor. < http://www.cflri.ca/pdf/e/2000pam.pdf> (Accessed on July 15, 2010).

- 9.Active Healthy Kids Canada Report Card 2009. < http://www.activehealthykids.ca/ecms.ashx/ReportCard2009/AHKC-Longform_WEB_FINAL.pdf> (Accessed on July 15, 2010).

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Physical activity levels among children aged 9–13 years-United States, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:785–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Annual Report on Ontario’s Schools 2008. < http://www.peopleforeducation.com/reportonschools08> (Accessed on July 15, 2010).

- 12.The Canadian Association for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance. Time to move 2005. < http://www.cahperd.ca/eng/advocacy/tools/documents/timetomove.pdf> (Accessed on July 15, 2010).

- 13.Lee SM, Burgeson CR, Fulton JE, Spain CG. Physical education and physical activity: Results from the school health policies and programs study 2006. J Sch Health. 2007;77:435–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Advisory Committee on Healthy Active Living for Children and Youth Healthy active living for children and youth. Paediatr Child Health. 2002;7:339–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nader PR. Frequency and intensity of activity of third-grade children in physical education. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:185–90. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKenzie TL, Nader PR, Strikmiller PK, et al. School physical education: Effect of the child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health. Prev Med. 1996;25:423–31. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Active Healthy Kids Canada Report Card 2009 Summary. < http://www.activehealthykids.ca/Modules/~cms.com/ecms.ashx/ExecSummary/AHK_ReportCard_ExecSummary_ENG.pdf> (Accessed on July 15, 2010).

- 18.Verstraete SJ, Cardon GM, De Clercq DL, De Bourdeaudhuij IM. Increasing children’s physical activity levels during recess periods in elementary schools: The effects of providing game equipment. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16:415–9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]