Plant growth and development is exquisitely tuned to the environment. The capacity for plants to adapt to myriad environmental stimuli is mediated by hormones that regulate virtually all aspects of development, physiology, and metabolism. The fatty acid-derived hormone jasmonate (JA) is a prime example of a small molecule that orchestrates phenotypic plasticity in rapidly changing environments (Howe and Jander, 2008; Browse, 2009a; Pieterse et al., 2009). Remarkable recent progress in dissecting the JA pathway has opened up new opportunities to study mechanisms of small-molecule sensing, transcriptional regulation, and interconnectivity between hormone response pathways. Here, I discuss recent advances in JA perception and signaling, and highlight areas of research that promise to contribute to the future of plant biology.

CORONATINE INSENSITIVE1 EXPANDS THE FAMILY OF UBIQUITIN LIGASE-COUPLED RECEPTORS

Receptors can be classified according to the biochemical activity affected by ligand binding. Membrane-bound receptors for cytokinins and brassinosteroids, for example, are linked to protein kinases, whereas perception of abscisic acid by its intracellular receptors is coupled to changes in protein phosphatase activity. An important conceptual advance in plant biology—and receptor biology in general—is the emergence of a novel class of receptors that exert effects on gene expression by linking changes in hormone levels to the activity of an E3 ubiquitin ligase, which in turn targets regulatory proteins for destruction by the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway (Santner et al., 2009; Tan and Zheng, 2009). Coupling between the receptor and its cognate E3 ligase may be direct, as in the case of the auxin receptor (TIR1), or indirect, as exemplified by the gibberellic acid receptor, GID1. In addition to these roles in hormone recognition, E3 ligases also catalyze key downstream steps in several hormone response pathways (Dreher and Callis, 2007).

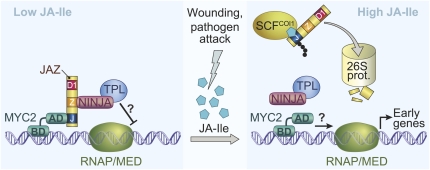

The F-box protein CORONATINE INSENSITIVE1 (COI1) plays a central and conserved role in JA signaling (Xie et al., 1998; Browse, 2009b). Recent progress in understanding how COI1 transduces the JA signal came from the discovery of JASMONATE ZIM-domain (JAZ) proteins as substrates of the E3 ubiquitin ligase SCFCOI1 (Chini et al., 2007; Thines et al., 2007; Yan et al., 2007; Chung et al., 2009). In cells containing low JA levels, JAZ proteins bind to and inhibit transcription factors that promote the expression of JA response genes (Fig. 1). JAZ-mediated repression is relieved in response to cues that activate the synthesis of JA and, more specifically, the amino acid conjugate jasmonoyl-l-Ile (JA-Ile). JA-Ile, but not jasmonic acid or other precursors of JA-Ile, stimulates physical interaction between COI1 and JAZ, which allows JAZs to be ubiquitinated by SCFCOI1 and subsequently degraded by the 26S proteasome. The (3R,7S) stereoisomer of JA-Ile [also known as (+)-7-iso-JA-Ile] is much more active than the (3R,7R) isomer in promoting COI1-JAZ interactions and thus is considered the natural ligand for the receptor (Fonseca et al., 2009; Chung et al., 2010; Suza et al., 2010). This emerging view of JA signaling, together with homology between COI1 and TIR1, suggests a common evolutionary origin between the auxin and JA response pathways (Xie et al., 1998; Katsir et al., 2008a). The existence of hundreds of uncharacterized ubiquitin ligases in plants (Smalle and Vierstra, 2004) raises the possibility that additional ubiquitin ligase-coupled receptors remain to be discovered.

Figure 1.

Current model of JA signal transduction. Low JA-Ile levels (left section) permit the accumulation of JAZ proteins (denoted with their Jas [J], ZIM/TIFY [Z], and Domain 1 [D1] regions) that bind to the bHLH-type transcription factor MYC2 (BD, DNA-binding domain; AD, activation domain). Repression of JA response genes involves binding of JAZ to NINJA, which contains an EAR motif that recruits the corepressor TPL. The mechanism by which TPL silences gene expression is unknown (?). In response to stress-related cues that activate JA-Ile synthesis, high levels of the hormone (right section) promote SCFCOI1-mediated ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of JAZs by the 26S proteasome (26S prot.). JAZ degradation relieves TPL-mediated repression of gene expression, and may also alleviate passive repression by allowing MYC2 to engage RNA polymerase II (RNAP) and/or the Mediator complex that links RNAP to MYC2.

ONE RECEPTOR OR MULTIPLE CORECEPTORS?

The ability of JA-Ile to stimulate COI1-JAZ interaction implies a direct role for this protein complex in hormone perception (Thines et al., 2007). The phytotoxin coronatine, which is a structural mimic of (3R,7S)-JA-Ile and a potent agonist of the receptor, binds reversibly and with high affinity (Kd approximately 20 nm) to COI1-JAZ complexes in crude tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) leaf extracts (Katsir et al., 2008b). These and other studies (Melotto et al., 2008; Fonseca et al., 2009; Yan et al., 2009) demonstrate that COI1 is an essential component of the receptor for JA-Ile and coronatine. Yan et al. (2009) used a photoaffinity approach to show that heterologously expressed COI1 binds directly to a synthetic derivative of coronatine, albeit with unknown affinity. These workers also used molecular modeling to identify a site on the surface of COI1 that can potentially bind JA-Ile and coronatine.

Despite these recent advances, we have yet to arrive at a satisfactory understanding of how JAZs are recruited to COI1 in a ligand-dependent manner. The conclusion that COI1 alone binds JA-Ile and therefore functions as the receptor (Yan et al., 2009) does not evoke a requirement for JAZ in the initial phase of hormone perception, but rather indicates that binding of JA-Ile by COI1 is the first step in JA signal transduction. Validation of this model will require the demonstration that JA-Ile binds reversibly and saturably to purified COI1 and, importantly, with an affinity that is commensurate with the effective in vivo concentration of JA-Ile. Low-affinity binding of JA-Ile to COI1 would support an alternative model in which COI1-JAZ coreceptor complexes are the biologically relevant unit for ligand recognition and transduction of the hormone signal. Binding of small-molecule hormones to sites on soluble receptors to engage protein-protein interaction with associated coreceptors is an emerging structural theme in plant biology (Sheard and Zheng, 2009; Raghavendra et al., 2010). Numerous JAZ isoforms and splice variants that differentially associate with COI1 (Yan et al., 2007; Chung and Howe, 2009; Chung et al., 2010) could potentially generate a repertoire of coreceptor complexes with a range of stabilities and signaling functions, thus providing a cellular mechanism to measure and respond appropriately to fluctuating JA-Ile levels.

As beautifully illustrated for other plant hormone receptors, structural biology holds great promise for unlocking the still-hidden secrets of the JA receptor. It will be particularly interesting to see how the structure of the COI1 receptor compares to that of the auxin receptor. Although TIR1 and COI1 likely have overall structural similarity (Tan et al., 2007; Yan et al., 2009), regions within the Aux/IAA and JAZ substrates (domain II and Jas motif, respectively) that interact with TIR1 and COI1 do not show sequence similarity. It thus remains to be determined whether the molecular glue model of auxin action (Tan et al., 2007) extends to JA-Ile, or whether JA-Ile promotes COI1-JAZ interaction by a fundamentally different mechanism. A complete answer to this question should include assessment of the role of TIR1’s inositol phosphate cofactor in auxin perception (Tan et al., 2007) and whether COI1 uses a similar cofactor. Structure-based knowledge of how plant hormones engage their cognate receptors will have applications far beyond plant biology, including the development of tools for conditional control of protein stability (Nishimura et al., 2009) and, potentially, design of drugs that promote protein-protein interaction. Insight into the evolutionary origins of F-box proteins as small-molecule sensors will be aided by studies of hormone signaling pathways in ancient land plants such as Physcomitrella patens (Hayashi et al., 2008).

JAZ GOES TOPLESS

A major advance in our understanding of how JAZ proteins squelch the expression of JA-responsive genes was recently reported by Pauwels et al. (2010), who used a powerful affinity purification approach to identify proteins that interact with JAZ1. A member of the ABI-FIVE BINDING PROTEIN family called NINJA (for Novel Interactor of JAZ) was identified as an adaptor protein that interacts with the ZIM domain of most JAZs (Fig. 1). Remarkably, NINJA contains an EAR (for ERF-associated amphiphilic repression) motif that recruits the corepressor TOPLESS (TPL), which previously was shown to interact with an EAR motif on Aux/IAA substrates of TIR1 to repress auxin responses (Szemenyei et al., 2008; Pauwels et al., 2010). This exciting finding indicates that the corepressor function of TPL is modular and can be plugged into multiple hormone response pathways via the many EAR-motif-containing proteins in plant cells (Kazan, 2006). Physical interaction of the NINJA/TPL complex with the ZIM domain of JAZ is supported by previous genetic studies showing that repression of JA signaling by the JAZ10.4 splice variant is dependent on the TIFY motif within the ZIM domain (Chung and Howe, 2009). That the ZIM/TIFY domain also mediates homo- and heteromeric interactions between JAZ proteins (Chini et al., 2009; Chung and Howe, 2009) is consistent with the identification of both NINJA and JAZ12 in the multiprotein complex purified with a JAZ1 bait (Pauwels et al., 2010).

This updated view of the JA response pathway indicates that JAZs are a scaffold on which the NINJA/TPL corepressor complex is assembled. Through direct interaction with MYC2 and related transcription factors, JAZs target corepressor complexes to JA-responsive genes (Fig. 1). Proteolytic removal of the JAZ scaffold by the JA-Ile/SCFCOI1 pathway effectively uncouples the corepressor from its target genes. Additional studies are needed to determine whether TPL actively represses JA response genes by recruiting histone deacetylases or other enzymes involved in chromatin remodeling (Krogan and Long, 2009). The relatively weak JA-related phenotypes exhibited by ninja and tpl mutants raise the possibility that JAZs repress transcription by other mechanisms, for example by obstructing access of MYC2 to the basal transcription machinery or the Mediator complex that bridges RNA polymerase II to MYC2 (Fig. 1; Kidd et al., 2009). Future models designed to explain the JA-Ile-induced switch between transcriptional repression and activation should account for the observation that early JA response genes are activated very rapidly (<15 min) in response to increased levels of endogenous JA-Ile (Chung et al., 2008; Glauser et al., 2008; Koo et al., 2009).

The ability of the ZIM/TIFY domain to promote JAZ interaction with both NINJA and other JAZs raises the interesting question of how JAZ-JAZ partnering affects JA signaling. A scenario in which JAZs are competitive inhibitors of NINJA binding predicts that JAZ-JAZ complexes may impede TPL-dependent gene silencing. It will be informative to determine whether JAZ dimerization (or higher order oligomerization) alters the affinity of JAZ for COI1 and MYC2. It is conceivable, for example, that JAZ-JAZ dimers nucleate the assembly of large multiprotein complexes in which NINJA/TPL and COI1/MYC2 are simultaneously bound to the ZIM/TIFY domain and Jas motif, respectively. In this context, large-scale protein-protein interaction networks involving JAZ family members may provide an attractive opportunity to study how supramolecular complexes link hormone action to changes in gene expression.

INTERCONNECTIVITY OF JA SIGNALING

Increasing evidence indicates that JA responses are highly integrated with other hormone pathways (Kazan and Manners, 2008; Ballaré, 2009; Pieterse et al., 2009). Current knowledge of the core JA signaling components (Fig. 1) creates new opportunities to understand how these pathways are interconnected at the molecular and cellular levels, presumably to optimize plant growth and fitness in changing environments. Of particular importance for advancing a mechanistic view of hormone cross talk is the identification of signaling components that are shared by two or more pathways, or components from individual pathways that physically interact to modify signal output. Notable examples include the role of MYC2 in coordinating the JA, ethylene, and abscisic acid response pathways (Kazan and Manners, 2008), and of JAZ proteins in integrating JA and phytochrome responses (Moreno et al., 2009; Robson et al., 2010). Shared signaling components also explain interconnectivity between the JA and auxin response pathways (Tiryaki and Staswick, 2002). More recent work (Pauwels et al., 2010) raises the possibility that pools of TPL generated in response to JAZ turnover may be free to engage Aux/IAA proteins, which could account for rapid repression of auxin response genes in JA-stimulated cells (Cheong et al., 2002).

Future progress in elucidating mechanisms of JA cross talk will benefit from the advanced genetic and bioinformatics tools available for model plants such as rice (Oryza sativa) and Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and, increasingly, nonmodel systems as well. Equally important will be the application of biochemical and cell biological approaches to identify multiprotein complexes, and the manner in which signaling information is spatially organized and processed within these complexes. These efforts will be aided by deep knowledge of the JA biosynthetic pathway and the ability to genetically manipulate endogenous levels of JA-Ile. Construction of predictive signaling network models to explain hormone-mediated responses may ultimately facilitate efforts to develop crops with increased yield and enhanced resistance to biotic and abiotic stress. Ubiquitin ligase-coupled receptors, which function to integrate information about intracellular hormone levels with changes in gene expression, promise to figure prominently in these networks.

Acknowledgments

I wish to acknowledge the many current and former lab members who have contributed to our work on JA. I also thank Marlene Cameron and Karen Bird for assistance with graphics and editing, respectively.

References

- Ballaré CL. (2009) Illuminated behaviour: phytochrome as a key regulator of light foraging and plant anti-herbivore defence. Plant Cell Environ 32: 713–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browse J. (2009a) Jasmonate passes muster: a receptor and targets for the defense hormone. Annu Rev Plant Biol 60: 183–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browse J. (2009b) The power of mutants for investigating jasmonate biosynthesis and signaling. Phytochemistry 70: 1539–1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong YH, Chang HS, Gupta R, Wang X, Zhu T, Luan S. (2002) Transcriptional profiling reveals novel interactions between wounding, pathogen, abiotic stress, and hormonal responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 129: 661–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chini A, Fonseca S, Chico JM, Fernandez-Calvo P, Solano R. (2009) The ZIM domain mediates homo- and heteromeric interactions between Arabidopsis JAZ proteins. Plant J 59: 77–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chini A, Fonseca S, Fernandez G, Adie B, Chico JM, Lorenzo O, Garcia-Casado G, Lopez-Vidriero I, Lozano FM, Ponce MR, et al. (2007) The JAZ family of repressors is the missing link in jasmonate signalling. Nature 448: 666–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HS, Cooke TF, DePew CL, Patel LC, Ogawa N, Kobayashi Y, Howe GA. (2010) Alternative splicing expands the repertoire of dominant JAZ repressors of jasmonate signaling. Plant J 63: 613–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HS, Howe GA. (2009) A critical role for the TIFY motif in repression of jasmonate signaling by a stabilized splice variant of the JASMONATE ZIM-domain protein JAZ10 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 131–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HS, Koo AJK, Gao X, Jayanty S, Thines B, Jones AD, Howe GA. (2008) Regulation and function of Arabidopsis JASMONATE ZIM-domain genes in response to wounding and herbivory. Plant Physiol 146: 952–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HS, Niu Y, Browse J, Howe GA. (2009) Top hits in contemporary JAZ: an update on jasmonate signaling. Phytochemistry 70: 1547–1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreher K, Callis J. (2007) Ubiquitin, hormones and biotic stress in plants. Ann Bot (Lond) 99: 787–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca S, Chini A, Hamberg M, Adie B, Porzel A, Kramell R, Miersch O, Wasternack C, Solano R. (2009) (+)-7-iso-Jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine is the endogenous bioactive jasmonate. Nat Chem Biol 5: 344–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauser G, Grata E, Dubugnon L, Rudaz S, Farmer EE, Wolfender JL. (2008) Spatial and temporal dynamics of jasmonate synthesis and accumulation in Arabidopsis in response to wounding. J Biol Chem 283: 16400–16407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Tan X, Zheng N, Hatate T, Kimura Y, Kepinski S, Nozaki H. (2008) Small-molecule agonists and antagonists of F-box protein-substrate interactions in auxin perception and signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 5632–5637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe G, Jander G. (2008) Plant immunity to insect herbivores. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59: 41–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsir L, Chung HS, Koo AJK, Howe GA. (2008a) Jasmonate signaling: a conserved mechanism of hormone sensing. Curr Opin Plant Biol 11: 428–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsir L, Schilmiller AL, Staswick PE, He SY, Howe GA. (2008b) COI1 is a critical component of a receptor for jasmonate and the bacterial virulence factor coronatine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 7100–7105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazan K. (2006) Negative regulation of defence and stress genes by EAR-motif-containing repressors. Trends Plant Sci 11: 109–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazan K, Manners JM. (2008) Jasmonate signaling: toward an integrated view. Plant Physiol 146: 1459–1468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd BN, Edgar CI, Kumar KK, Aitken EA, Schenk PM, Manners JM, Kazan K. (2009) The mediator complex subunit PFT1 is a key regulator of jasmonate-dependent defense in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 2237–2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo AJK, Gao XL, Jones AD, Howe GA. (2009) A rapid wound signal activates the systemic synthesis of bioactive jasmonates in Arabidopsis. Plant J 59: 974–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan NT, Long JA. (2009) Why so repressed? Turning off transcription during plant growth and development. Curr Opin Plant Biol 12: 628–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melotto M, Mecey C, Niu Y, Chung HS, Katsir L, Yao J, Zeng W, Thines B, Staswick P, Browse J, et al. (2008) A critical role of two positively charged amino acids in the Jas motif of Arabidopsis JAZ proteins in mediating coronatine- and jasmonoyl isoleucine-dependent interaction with the COI1 F-box protein. Plant J 55: 979–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno JE, Tao Y, Chory J, Ballaré CL. (2009) Ecological modulation of plant defense via phytochrome control of jasmonate sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 4935–4940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura K, Fukagawa T, Takisawa H, Kakimoto T, Kanemaki M. (2009) An auxin-based degron system for the rapid depletion of proteins in nonplant cells. Nat Methods 6: 917–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels L, Barbero GF, Geerinck J, Tilleman S, Grunewald W, Perez AC, Chico JM, Bossche RV, Sewell J, Gil E, et al. (2010) NINJA connects the co-repressor TOPLESS to jasmonate signalling. Nature 464: 788–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse CMJ, Leon-Reyes A, Van der Ent S, Van Wees SCM. (2009) Networking by small-molecule hormones in plant immunity. Nat Chem Biol 5: 308–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra AS, Gonugunta VK, Christmann A, Grill E. (2010) ABA perception and signalling. Trends Plant Sci 15: 395–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson F, Okamoto H, Patrick E, Harris SR, Wasternack C, Brearley C, Turner JG. (2010) Jasmonate and phytochrome A signaling in Arabidopsis wound and shade responses are integrated through JAZ1 stability. Plant Cell 22: 1143–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santner A, Calderon-Villalobos LI, Estelle M. (2009) Plant hormones are versatile chemical regulators of plant growth. Nat Chem Biol 5: 301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheard LB, Zheng N. (2009) Plant biology: signal advance for abscisic acid. Nature 462: 575–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalle J, Vierstra RD. (2004) The ubiquitin 26S proteasome proteolytic pathway. Annu Rev Plant Biol 55: 555–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suza WP, Rowe ML, Hamberg M, Staswick PE. (2010) A tomato enzyme synthesizes (+)-7-iso-jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine in wounded leaves. Planta 231: 717–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szemenyei H, Hannon M, Long JA. (2008) TOPLESS mediates auxin-dependent transcriptional repression during Arabidopsis embryogenesis. Science 319: 1384–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Calderon-Villalobos LI, Sharon M, Zheng C, Robinson CV, Estelle M, Zheng N. (2007) Mechanism of auxin perception by the TIR1 ubiquitin ligase. Nature 446: 640–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Zheng N. (2009) Hormone signaling through protein destruction: a lesson from plants. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296: E223–E227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thines B, Katsir L, Melotto M, Niu Y, Mandaokar A, Liu G, Nomura K, He SY, Howe GA, Browse J. (2007) JAZ repressor proteins are targets of the SCFCOI1 complex during jasmonate signalling. Nature 448: 661–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiryaki I, Staswick PE. (2002) An Arabidopsis mutant defective in jasmonate response is allelic to the auxin-signaling mutant axr1. Plant Physiol 130: 887–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie DX, Feys BF, James S, Nieto-Rostro M, Turner JG. (1998) COI1: an Arabidopsis gene required for jasmonate-regulated defense and fertility. Science 280: 1091–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan JB, Zhang C, Gu M, Bai ZY, Zhang WG, Qi TC, Cheng ZW, Peng W, Luo HB, Nan FJ, et al. (2009) The Arabidopsis CORONATINE INSENSITIVE1 protein is a jasmonate receptor. Plant Cell 21: 2220–2236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Stolz S, Chetelat A, Reymond P, Pagni M, Dubugnon L, Farmer EE. (2007) A downstream mediator in the growth repression limb of the jasmonate pathway. Plant Cell 19: 2470–2483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]