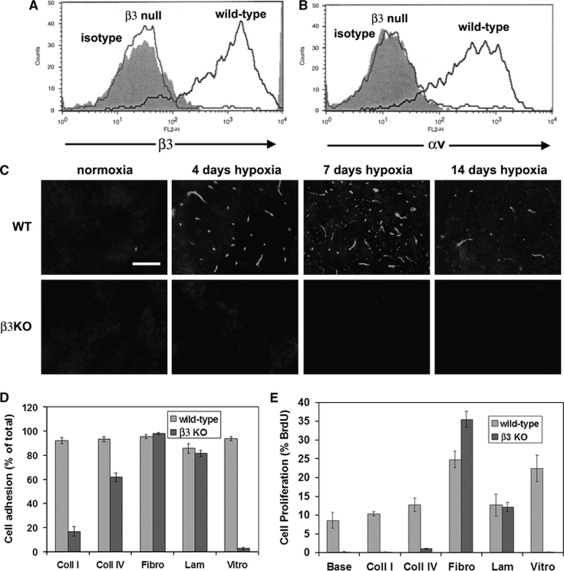

Figure 4.

Characterization of brain endothelial cells (BEC) derived from β3 integrin-null mice. (A and B) Wild-type or β3 integrin-null BEC were cultured on fibronectin and expression of the β3 (A) or αv (B) integrin subunits analyzed using flow cytometry. Note that in contrast to wild-type BEC, β3 integrin-null BEC showed a total absence of both the β3 and αv subunits. (C) Confirmation of the absence of the hypoxia induction of β3 integrin expression in β3 integrin-null mice. Scale bar=50 μm. Note that in contrast to the wild-type central nervous system (CNS), where strong hypoxia induction of the β3 integrin subunit was observed, vessels in the β3 integrin-null CNS showed a total lack of β3 integrin. (D) One-hour adhesion assays were performed, with adhesion expressed as the percentage of cells adherent to each substrate; all points represent the mean±s.e.m. of three experiments. Note that wild-type BEC attached well to all extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. In contrast, β3 integrin-null BEC showed marked adhesive defects on vitronectin and collagen I, and a mild defect on collagen IV. (E) BEC proliferation on different ECM substrates was examined over 16 h, and expressed as the percentage of BEC that incorporated 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU); all points represent the mean±s.e.m. of three experiments. Note that fibronectin and vitronectin significantly promoted proliferation of wild-type BEC, relative to uncoated glass. Proliferation of β3 integrin-null BEC was almost totally abolished on vitronectin, collagen I, and collagen IV, but significantly increased on fibronectin, relative to wild-type cells.