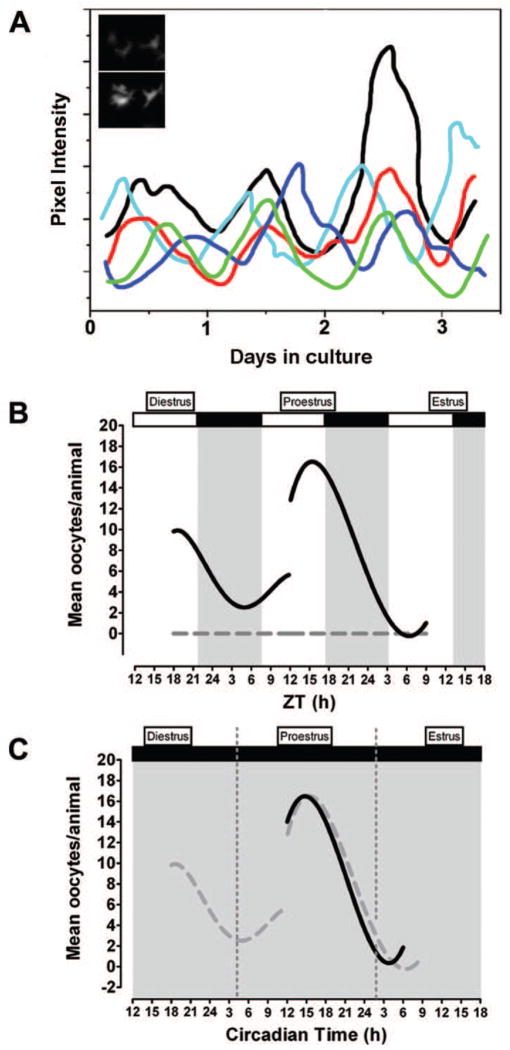

Figure 1.

A circadian clock in the rat ovary may contribute to the timing of ovulation. (a) Schematic representation showing circadian rhythms of period1-luciferase gene expression in individual granulosa/thecal cells. Inset graph: Images of trough (top panel) and peak (bottom panel) per1-luciferase gene expression in a representative granulosa/thecal cell recorded with an intensified CCD camera. Based on data from [7]. Schematic representation of (b) diurnal and (c) circadian rhythms of ovulation in response to exogenous LH in the absence of endogenous LH secretion. Animals housed under (b) a 12:12 L:D cycle or (c) constant dim light were injected with the GnRH receptor antagonist Cetrorelix on diestrus or proestrus to suppress endogenous LH secretion followed by timed injections of equine LH (solid black lines). LH-treatment during the subjective night on both diestrus and proestrus (L:D) or proestrus alone resulted in more frequent ovulation and significantly more oocytes/ovulation. Animals treated with sterile saline (gray dashed line in (b)) failed to ovulate regardless of injection time. The open and solid bars at the top of the figure indicate the light and dark portions of the L:D cycle. The solid gray background in (c) indicates that animals were maintained under constant dim light. Dashed gray lines in (f) are data from (b) re-plotted to emphasize the similarity of the results. Panels (b, c) modified from [60].