Abstract

Human leishmaniasis is a major public health problem in many countries, but chemotherapy is in an unsatisfactory state. Leishmania major phosphodiesterases (LmjPDEs) have been shown to play important roles in cell proliferation and apoptosis of the parasite. Thus LmjPDE inhibitors may potentially represent a novel class of drugs for the treatment of leishmaniasis. Reported here are the kinetic characterization of the LmjPDEB1 catalytic domain and its crystal structure as a complex with 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) at 1.55 Å resolution. The structure of LmjPDEB1 is similar to that of human PDEs. IBMX stacks against the conserved phenylalanine and forms a hydrogen bond with the invariant glutamine, in a pattern common to most inhibitors bound to human PDEs. However, an extensive structural comparison reveals subtle but significant differences between the active sites of LmjPDEB1 and human PDEs. In addition, a pocket next to the inhibitor binding site is found to be unique to LmjPDEB1. This pocket is isolated by two gating residues in human PDE families, but constitutes a natural expansion of the inhibitor binding pocket in LmjPDEB1. The structure particularity might be useful for the development of parasite-selective inhibitors for the treatment of leishmaniasis.

Keywords: Leishmaniasis, parasite inhibitor selectivity, cAMP phosphodiesterase

The leishmaniases are a complex of clinical diseases that comprises three main syndromes: local or disseminated ulcerative skin lesions (cutaneous leishmaniasis, CL), destructive mucosal inflammation (mucosal leishmaniasis, ML), and fatal visceral infection (visceral leishmaniasis, VL). They are caused by about 20 species of the protozoan Leishmania that are all transmitted by the bite of female sand flies (Kamhawi et al., 2006; Reithinger and Dujardin, 2007). The diseases are endemic in developing countries in tropical/sub-tropical regions and also in Southern Europe, but have increasingly been introduced into the industrialized countries through economic globalization and travel (Schwartz, et al., 2006). An additional problem is the rapid increase in the number of HIV/leishmaniasis co-infections that exacerbate both diseases (Desjeux and Alvar, 2003). At present, no vaccine is available, and chemotherapy is severely deficient (Kedzierski et al., 2006; Croft et al., 2006; Mishra et al., 2007). The pentevalent antimonials such as glucantime® have been the main anti-leishmaniasis drugs for over 60 years, but their efficacy is diminishing due to drug–resistance in some regions of the world such as Bihar in India (Loiseau and Bories, 2006; Mishra et al., 2007; Ashutosh et al., 2007). Other antileishmanials such as Amphotericin B (AmBisome®), paramomycin, pentamidine (Pentacarinat®) and miltefosin (Miltex®) are available in cases where antimonials lack efficacy, but their therapeutic windows are limited. Thus, the development of novel and better anti-leishmanials is necessary to meet an urgent medical need on a global scale. Inhibitors of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases (PDEs) may represent such a category of novel drugs for the treatment of human leishmaniasis.

PDEs control the cellular concentration of the second messengers cAMP and cGMP that are key regulators of many important physiological processes (Bender and Beavo, 2006; Lugnier 2006; Omori and Kotera 2006; Counti and Beavo, 2007; Ke and Wang, 2007). The human genome contains twenty-one PDE genes that are categorized into eleven families. Alternative mRNA splicing generates about a hundred PDE isoforms distributed over various human tissues. Family-selective inhibitors of human PDE families have been widely studied as therapeutics, including cardiotonics, erection enhancers, vasodilators, anti-psychotics, smooth muscle relaxants, antidepressants, anti-thrombotics, anticancer drugs, and agents for the treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, as well as for the improvement of learning and memory (Rotella 2002; Lipworth 2005; Castro et al 2005; Houslay et al 2005; Lerner et al., 2006; Blokland et al 2006; Menniti et al 2006). The media star among these inhibitors is certainly sildenafil, a PDE5-selective inhibitor that has been successfully deployed as a drug for the treatment of male erectile dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension (Rottela 2002; Galie et al., 2006).

The genome of the protozoal parasite Leishmania major contains five PDE genes encoding LmjPDEA, LmjPDEB1, LmjPDEB2, LmjPDEC and LmjPDED, respectively (Kunz et al., 2005; Rascon et al, 2000; Johner et al., 2006). Two of these, LmjPDEB1 and LmjPDEB2 are tandemly arranged on chromosome 15 and share extensive similarity in their overall architecture. They contain two GAF-domains in their N-terminal regions. Their catalytic domains are essentially identical, except for a short stretch of sequence between Ala798 and Arg823 of LmjPDEB1. Early studies showed that three human PDE inhibitors (etazolate, dipyridamole, and trequinsin) inhibit the proliferation of L. major promastigotes and L. infantum amastigotes with IC50 values in the range of 30-100 μM (Johner et al., 2006). In addition, 5,7,4’-trihydroxyflavan exhibited toxic activity on amastigotes of L. amazonensis (Mishra et al., 2007), and the flavonoids luteolin and quercetin caused cell cycle arrest of L. donovani promastigotes in the G1 phase and increased cell apoptosis (Salem and Werbovetz, 2006). Since the flavonoids are nonselective inhibitors of the human PDEs (Peluso, 2006), these preliminary experiments suggested that selective inhibitors of LmjPDEs may potentially represent a novel class of drugs for the treatment of leishmaniasis. However, neither selective LmjPDE inhibitors nor structures of LmjPDEs are available at present. Here, we report the kinetic characterization and the crystal structure of the catalytic domain of LmjPDEB1 in complex with 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX). A comparison between the structures of LmjPDEB1 and human PDEs reveals a unique pocket in the LmjPDEB1 structure, which may thus be useful for the design of parasite selective inhibitors for the treatment of leishmaniasis.

RESULTS and DISCUSSION

Enzymatic properties

The catalytic domain of LmjPDEB1 (residues 582-940) has a Km of 20.6 μM and a kcat of 2.7 s-1 for cAMP. The catalytic efficiency constant kcat/Km is 0.13 s-1 μM-1. For the catalysis using cGMP as the substrate, the Km is estimated to be > 1mM and kcat could not be measured because cGMP at concentrations >2 mM co-precipitated with the product GMP under the assay condition. Our assay confirms the earlier report that LmjPDEB1 is cAMP specific (Johner et al., 2006). However, the Km value of the LmjPDEB1 catalytic domain is higher than the Km of 1 μM for the full-length protein (Johner et al., 2006). This difference likely reflects the contribution of the regulatory GAF domains of the protein. We speculate that cAMP binds to the GAF domain of LmjPDEB1 and causes conformational changes at the active site, thus impacting the Km of the substrate cAMP. In fact, this allosteric effect was first reported by Beavo's group for trypanosome PDEB2 (Laxman et al., 2005). TbrPDEB2 was shown to be an allosteric enzyme with a Hill coefficient of 1.75 and to have a Km value of > 44 μM for the isolated catalytic domain and of 4.5 μM for the full-length protein (Laxman et al., 2005). Since LmjPDEB1 shares a high homology with TbrPDEB2, the different Km values for the holoenzyme of LmjPDEB1 and its isolated catalytic domain may imply that LmjPDEB1 is an allosteric enzyme.

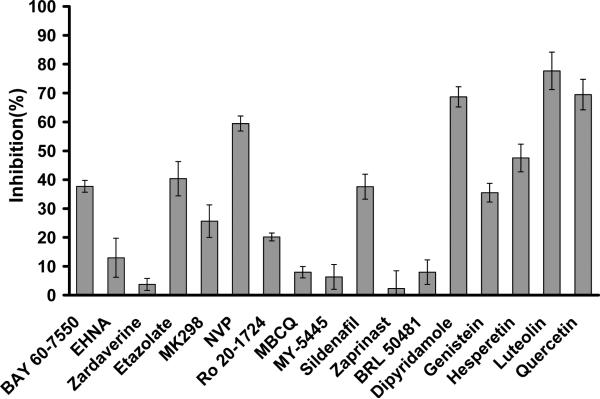

Since no LmjPDE-selective inhibitors are available at present, several inhibitors of human PDEs were tested for their inhibition of LmjPDEB1. However, most human PDE inhibitors do not effectively inhibit LmjPDEB1, in consistence with an earlier report (Johner et al., 2006). For example, the PDE4-selective inhibitor rolipram showed an IC50 value of 330 μM for the LmjPDEB1 catalytic domain, and the non-selective inhibitor IBMX had an IC50 value of 580 μM. Thus, a single-concentration assay was performed for a quick screen of other PDE inhibitors (Fig. 1). Among the tested inhibitors, luteolin, a flavonoid and a non-selective inhibitor of human PDEs (Peluso, 2006), is most potent and shows about 80% inhibition of the LmjPDEB1 activity at 20 μM inhibitor. In addition, 20 μM dipyridamole and quercetin inhibit about 70% activity of the LmjPDEB1 catalytic domain (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of the LmjPDEB1 catalytic domain by human PDE inhibitors. The single-point assay was performed at 0.04 μM cAMP and 20 μM inhibitors. The error bars were calculated from 3-4 repeated measurements. BAY 60-7550 and EHNA are PDE2 selective inhibitors. Zardaverine is a PDE3/PDE4 dual selective inhibitor. Etazolate, MK298 (L-869298), NVP (4-[8-(3-nitrophenyl)-[1,7]-naphthyridin-6-yl]benzoic acid), and Ro 20-1724 are PDE4 selective inhibitors. MBCQ, MY-5445, sildenafil, and zaprinast are PDE5 selective inhibitors. BRL 50481 is a PDE7 selective inhibitor. Dipyridamole inhibits several PDEs, including PDE5, 6, 8, 10 and 11. Flavonoids of genistein, hesperetin, luteolin, and quercetin are non-selective PDE inhibitors.

Structural architecture

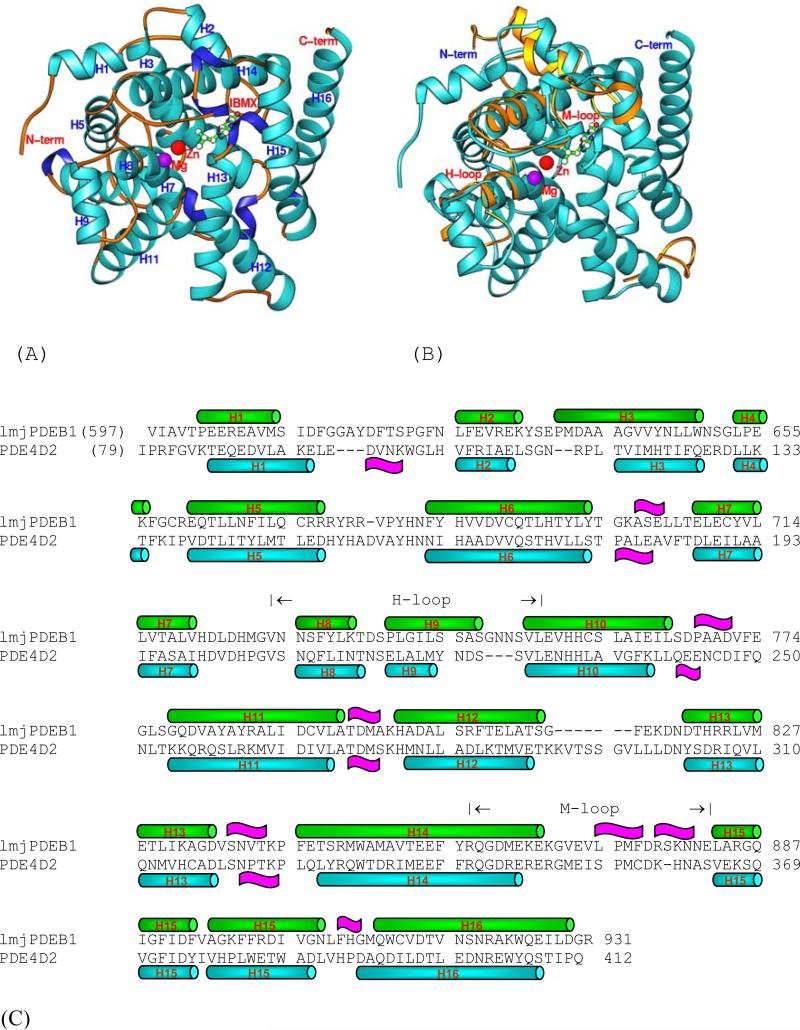

The catalytic domain of LmjPDEB1 (residues 582-940) was used for the crystallization, but only residues 597-931 had good electron density and were traced without ambiguity. The remaining N- and C-terminal residues were disordered. The crystallographic asymmetric unit contains two molecules of LmjPDEB1, which apparently form a dimer by a 2-fold symmetry axis. However, this crystallographic dimer is not comparable with any of the human PDEs, and thus it is not clear whether the dimer is biologically relevant. The superposition of the two catalytic domains of LmjPDEB1 in the crystallographic asymmetric unit yielded a root-mean squared deviation (RMSD) of 0.33 Å for all the Cα atoms in the structure, indicating the similarity of the two molecules. The catalytic domain of LmjPDEB1 comprises sixteen α-helices but no β-strands (Fig. 2). Two divalent metal ions occupy the bottom of the catalytic pocket. Zinc and magnesium were used, without verification, in the structure refinement and had comparable B-factors with the overall average for protein atoms, suggesting a reasonable assignment. The zinc ion coordinates with His685, His721, Asp722, Asp835, and two bound water molecules. The magnesium ion coordinates with Asp722 and five water molecules. The octahedral configuration of the two divalent metals in LmjPDEB1 is comparable with those in the human PDEs.

Fig. 2.

The structure of LmjPDEB1. (A) Ribbon diagram. (B) The superposition of LmjPDEB1 (cyan ribbons) over PDE4D2. Only the PDE4D loops (golden ribbons) with large positional differences are shown. (C) The sequence alignment between LmjPDEB1 and PDE4D2. Symbol  represents α-helices and

represents α-helices and  represent 310 helices.

represent 310 helices.

The structure superposition between LmjPDEB1 and human PDEs yielded RMSDs of 1.7, 1.8, 1.3, 1.5, 1.8, 2.0, 1.5, and 1.6 Å, respectively for the 270, 282, 266, 277, 265, 290, 292, and 289 comparable Cα atoms of unliganded PDE1B (Zhang et al., 2004), unliganded PDE2A (Iffland et al., 2005), PDE3B-IBMX (Scaping et al., 2005), PDE4D2-IBMX (Huai et al., 2004a), PDE5A1-IBMX (Huai et al., 2004a), PDE7A1-IBMX (Wang et al., 2005), PDE9A2-IBMX (Huai et al., 2004b), and PDE10A2-cAMP (Wang et al., 2007). This comparison indicates a similar topological folding of LmjPDEB1 and the human PDEs. Indeed, visible inspection on a graphic terminal showed that the core domain from helix H3 to H16 compares well with those of human PDE families, except for a few insertions/deletions (Fig. 2).

The superposition revealed four regions that exhibit significant differences between the structures of LmjPDEB1 and human PDEs. The N-terminal residues 597-617 and a loop around residue 814 of LmjPDEB1 showed positions and conformations different from the human PDEs (Fig. 2). Since the sequences of these two fragments are poorly comparable or have insertions/deletions in almost all parasite and human PDEs, the different conformations may be predictable. In addition, helix H9 of the H-loop (residues 729-754 in LmjPDEB1) and most residues in the M-loop (residues 858-882) of LmjPDEB1 exhibit significant positional shifts of as much as 3 Å for their Cα atoms from those of the human PDE families (Fig. 2). This difference is about twice the overall RMSD between the structures of LmjPDEB1 and human PDEs and is thus statistically significant. Since the H- and M-loops are directly involved in interaction with the inhibitors (Huai et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2006; Ke and Wang, 2007), their conformational changes appear to have enzymatic implications. However, further characterization is needed to understand the roles of the individual residues in the loops.

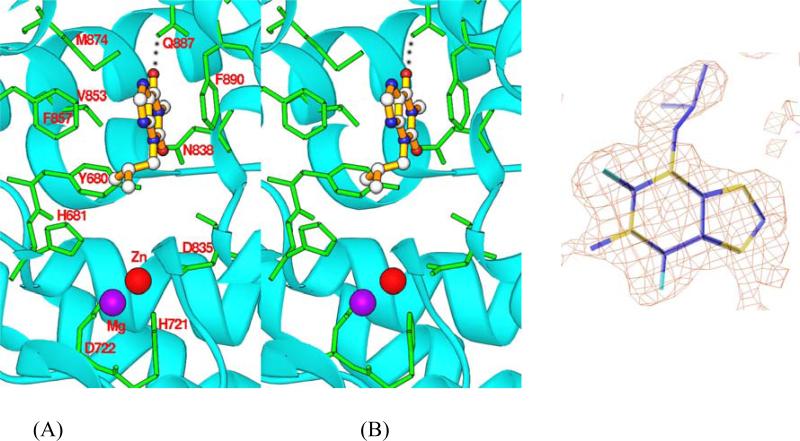

IBMX binding

IBMX is a non-selective inhibitor for most human PDE families, but it only weakly inhibits LmjPDEB1 with an IC50 value of 580 μM. IBMX binds to the active site of LmjPDEB1. The O6 atom of the xanthine ring of IBMX forms a hydrogen bond with Ne2 of Gln887 of LmjPDEB1 (Fig. 3). The xanthine ring stacks against Phe890 of LmjPDEB1 and also forms van der Waals’ contacts with residues Tyr680, Asn838, Val853, and Phe857. The isobutyl group of IBMX interacts with residues Tyr680, His681, Asn838, and Val853.

Fig. 3.

IBMX binding to LmjPDEB1. (A) A stereo-view of the IBMX binding at the active site of LmjPDEB1. The dotted line represents the hydrogen bond between IBMX and the side chain of glutamine. (B) Electron density for IBMX. The (Fo-Fc) map was calculated from the structure without IBMX and contoured at 3 sigmas.

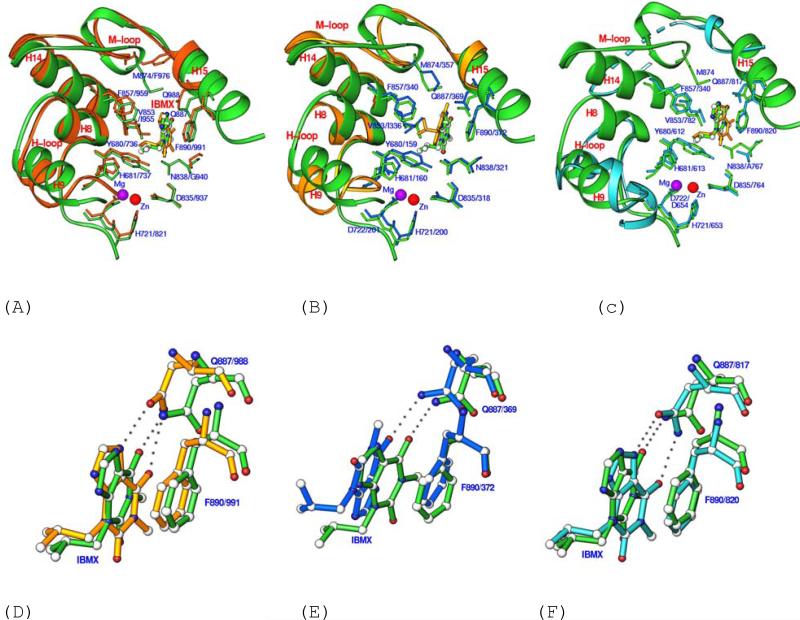

The binding of IBMX in the LmjPDEB1 structure is similar to that observed in the human PDEIBMX complexes. Two elements of IBMX binding to LmjPDEB1, the hydrogen bond with the invariant glutamine and the stack against phenylalanine, are conserved among LmjPDEB1 and human PDEs. In fact, these two elements are the common binding characteristics of almost all PDE inhibitors (Ke and Wang, 2007), whether or not they are selective or non-selective. Notably, the xanthine ring of IBMX in the LmjPDEB1 structure has the same orientation as it has in PDE3B, PDE5A (Fig. 4) and PDE9A (data not shown), but it is flipped by about 180° in PDE4D (Fig. 4) and PDE7A (data not shown). The different orientations of IBMX in the PDE structures may be understandable because the active site pockets of PDEs are much larger than the volume of substrates, IBMX, or other PDE inhibitors. For example, the active site of PDE4B has a volume of 440 Å3, in comparison with 232 Å3 of cAMP (Xu et al., 2000). Besides, IBMX forms two hydrogen bonds with PDE3B and PDE5A, but only one with PDE4D, PDE7A, PDE9A, and LmjPDEB1. The different numbers of hydrogen bonds in these PDE structures appear to be determined by the orientation of IBMX and by the position of the side chain of the invariant glutamine.

Fig. 4.

Superposition of the IBMX binding pocket of LmjPDEB1 (green ribbons and sticks) over those of PDE3B-IBMX (A), PDE4D2-IBMX (B), and PDE5A1-IBMX (C), and their detail views (D, E, F). In Figs. 4D, 4E, and 4F, the green bonds represent LmjPDEB1, gold for PDE3B, blue for PDE4D, and cyan for PDE5A. PDE3, PDE4, and PDE5 are dual-, cAMP-, and cGMP-specific enzymes, respectively. The superposition was produced by using all comparable residues in the catalytic domains. The dotted lines in PDE5A represent the disordered residues in the M-loop. The first portions of the labels represent the LmjPDEB1 residues while the second parts of the labels are for the human PDEs.

Similarities and differences between the active sites of LmjPDEB1 and human PDEs

To explore the possibility of designing parasite-selective inhibitors, the structure of LmjPDEB1 was superimposed over those of human PDEs by using all comparable residues in the catalytic domain (about 270 out of total 335 residues). Overall, the active sites of LmjPDEB1 and human PDEs compare well, including the four metal-binding residues (His685, His721, Asp722, Asp835), the important residues for the catalysis (His681 and His725), and the residues for inhibitor binding such as Phe890 (Fig. 4 and Table 2).

Table 2.

The sequence alignment of the metal-binding (*) and active site residues among leishmanial and human PDEs. The numbers in the parentheses are the distances between the Cα atoms of LmjPDEB1 and the available structures of human PDEs. The bold-faced numbers highlight the significant positional differences.

| 680 | 681 | 685 (*) | 721 (*) | 722 (*) | 725 | 797 | 835 (*) | 836 | 838 | 839 | 846 | 849 | 850 | 853 | 854 | 857 | 874 | 886 | 887 | 890 | 924 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LmjPDEB1 | Y | H | H | H | D | H | M | D | V | N | V | S | W | A | V | T | F | M | G | Q | F | W |

| LmjPDEB2 | Y | H | H | H | D | H | M | D | V | N | V | S | W | A | V | T | F | M | G | Q | F | W |

| LmjPDEA | Y | H | H | H | D | H | M | D | I | N | C | S | W | G | V | S | F | F | S | Q | F | W |

| LmjPDEC | Y | H | H | H | D | H | M | D | I | A | Q | A | W | L | I | V | M | G | G | Q | F | Y |

| LmjPDED | Y | H | H | H | D | H | M | D | I | N | C | Y | W | A | I | S | F | F | G | Q | F | W |

| hPDE1B | Y (0.55) | H (0.47) | H (0.71) | H (0.80) | D (0.85) | H (0.43) | M (0.49) | D (0.54) | I (0.34) | H (0.89) | P (0.85) | H (0.56) | W (0.62) | T (0.55) | L (0.54) | M (0.71) | F (0.61) | L (0.37) | S (2.17) | Q (1.23) | F (0.98) | N (1.82) |

| hPDE2A | Y (0.63) | H (0.64) | H (0.80) | H (0.74) | D (0.91) | H (0.97) | L (0.88) | D (1.04) | L (1.74) | D (1.95) | Q (1.57) | T (2.72) | I (1.45) | A (1.53) | I (0.95) | Y (1.39) | F (0.88) | M (1.33) | L (2.34) | Q (1.72) | F (0.70) | W (1.19) |

| hPDE3B | Y (0.70) | H (0.69) | H (0.86) | H (0.70) | D (0.82) | H (0.50) | L (0.27) | D (0.46) | I (0.70) | G (1.06) | P (1.08) | H (0.87) | W (0.67) | T (0.53) | I (0.81) | V (0.78) | F (0.80) | F (1.19) | L (2.39) | Q (1.73) | F (1.32) | W (0.93) |

| hPDE4D2 | Y (0.52) | H (0.64) | H (0.64) | H (0.82) | D (0.82) | H (0.47) | M (0.35) | D (0.62) | L (0.65) | N (0.60) | P (0.71) | Y (0.40) | W (0.30) | T (0.42) | I (0.35) | M (0.33) | F (0.46) | M (0.13) | S (1.72) | Q (1.02) | F (0.48) | Y (1.10) |

| hPDE5A | Y (0.47) | H (0.53) | H (0.45) | H (0.48) | D (0.50) | H (0.36) | L (0.99) | D (0.70) | L (1.01) | A (1.28) | I (1.13) | Q (1.12) | I (0.86) | A (0.61) | V (0.62) | A (0.53) | F (0.66) | L | M (1.26) | Q (0.87) | F (0.80) | W (1.46) |

| hPDE6A | Y | H | H | H | D | H | L | D | L | A | I | Q | V | A | V | A | F | M | L | Q | F | W |

| hPDE7A | Y (0.67) | H (0.68) | H (0.89) | H (1.20) | D (1.04) | H (0.33) | I (1.00) | D (0.78) | I (0.89) | N (0.93) | P (1.32) | S (1.09) | W (0.87) | S (0.96) | V (0.62) | T (0.62) | F (0.53) | L (1.51) | I (2.12) | Q (1.89) | F (0.90) | W (3.26) |

| hPDE8A | Y | H | H | H | D | H | M | D | V | N | P | C | W | A | I | S | Y | V | S | Q | F | W |

| hPDE9A | F (0.44) | H (0.40) | H (0.56) | H (0.81) | D (0.81) | H (0.41) | M (0.81) | D (0.82) | I (1.08) | N (1.19) | E (1.81) | A (1.61) | W (1.32) | V (1.14) | L (0.93) | L (1.09) | Y (0.62) | F (2.26) | A (1.14) | Q (0.44) | F (0.84) | Y (1.07) |

| hPDE10A | Y (0.23) | H (0.38) | H (0.53) | H (0.91) | D (0.77) | H (0.56) | L (1.21) | D (0.72) | L (1.29) | S (1.38) | V (1.08) | T (0.83) | T (1.04) | A (0.50) | I (0.28) | Y (0.69) | F (0.59) | M (0.22) | G (2.38) | Q (1.81) | F (0.98) | W (1.60) |

| hPDE11A | Y | H | H | H | D | H | L | D | L | A | V | S | V | A | V | T | F | I | L | Q | W | W |

However, subtle but significant differences are observed from the superposition. For human PDE1B, the largest positional displacement is associated with Ser420 of PDE1B or Gly886 of LmjPDEB1 (Table 2). For PDE2A, the following residues show significant positional differences (Table 2): Leu809 (Val836 of LmjPDEB1), Asp811 (Asn838), Thr819 (Ser846), Leu858 (Gly886), and Gln859 (Gln887). For PDE3B, Leu987 and Gln988 exhibit large positional displacements and Phe976 shows a marked conformational difference from Met874 of LmjPDEB1 (Fig. 4A). For PDE4D, the overall positional differences are relatively small (average of 0.6 Å for the 22 active site residues, Table 2), with the largest difference associated with Ser368 (Gly886 in LmjPDEB1, Fig. 4B). For PDE5A, the most notable change is the disorder of a part of the M-loop both in the unliganded form and in the complex with IBMX (Fig. 4C). This loop is well ordered in the complex with sildenafil (Huai et al., 2004a; Wang et al., 2006). For PDE7A, helix H15 shows significant positional changes, resulting in a movement of Ile412 and Gln413 (Table 2). For PDE9A, the movement of the M-loop is remarkable, as shown by the 2.3 Å difference between the Cα atoms of Phe441 of PDE9A and Met874 of LmjPDEB1 (Table 2). In PDE10A, the movement of helix H15 causes 2.4 and 1.8 Å shifts of the Cα atoms of Gly725 and Gln726 from Gly886 and Gln887 of LmjPDEB1. Since the active site residues in Table 2 are not involved in the lattice contacts in the crystals, their positional differences must reflect the intrinsic structural variations.

In summary, Gly886 and Gln887 of LmjPDEB1 show the most significant positional displacement (Table 2). Since the invariant glutamine (Gln887 of LmjPDEB1) has been proposed to play essential roles in the substrate and inhibitor binding (Ke and Wang, 2007), the positional variation of Gly886 and Gln887 must be an important factor that diminishes the binding of the human PDE inhibitors to LmjPDEB1. In addition, changes of Asn838, Val839, Ser846, and Met874 of LmjPDEB1 are also significant, and may impact on inhibitor binding. Therefore, we believe that multiple residues at the active site of LmjPDEB1 jointly determine the affinity of inhibitors. The positional and conformational differences between the active sites of LmjPDEB1 and human PDEs suggest the feasibility of designing LmjPDE selective inhibitors.

A unique pocket of LmjPDEB1 for inhibitor binding

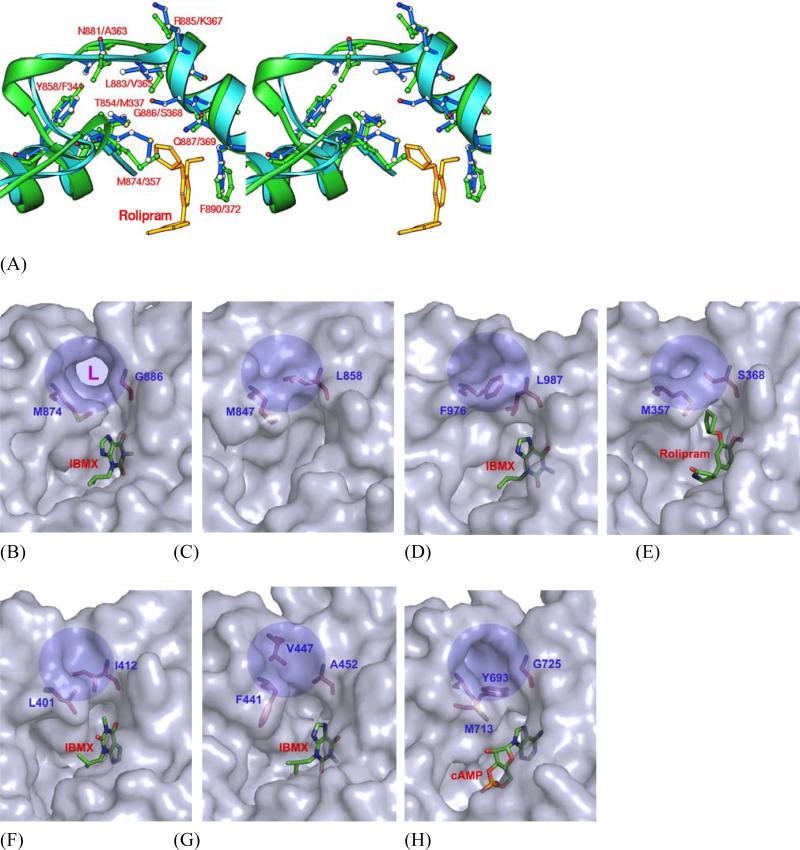

The most surprising finding of the structural study is the identification of a subpocket in LmjPDEB1, which is close to the binding of cyclic pentanyl ring of rolipram in PDE4 (Fig. 5). This pocket is made up of residues from the M-loop and helix H14, including Thr854, Tyr858, Met874, Asn881, Leu883, and Gly886 in LmjPDEB1. Three residues Thr854, Met874 and Gly886 of LmjPDEB1 are located at the entry of the subpocket. In most of human PDE families, the subpockets are isolated from the active sites by two entry residues: Met847 and Leu858 in PDE2A, Phe976 and Leu987 in PDE3B, Met357 and Ser368 in PDE4D2, Leu401 and Ile412 in PDE7A (Fig. 5). In PDE10A, Tyr693 plays a key role to obstruct the entry to the subpocket while Met713 and Gly725 are separated by 6.7 Å. In PDE9A, Phe441 and Ala452 do not block the path, but Val447 moves over by 3 Å into the pocket and thus fills it up (Fig. 5). It is interesting to note that the gating glycine (Gly886 in LmjPDEB1) exists in four of the five Lmj PDEs, but only in human PDE10, and shows the largest positional difference among the active site residues (Table 2). Because glycine is unique in that its backbone conformation can freely assume any angle, this glycine must represent a fundamental difference between most human and leishmania PDEs.

Fig. 5.

Putative Leishmania parasite pocket (L-pocket). (A) A stereo-view of the superposition of LmjPDEB1 (green ribbons, sticks, and labels) over PDE4D2 (cyan ribbons and blue sticks and labels). (B) Surface presentation of a unique L-pocket of LmjPDEB1 (shaded circle and marked with L) and equivalents of PDE2A (C), PDE3B (D), PDE4D (E), PDE7A (F), PDE9A (G), and PDE10A (H).

In the LmjPDEB1 structure, a separation of 7.5 Å between the Cα atoms of Met874 and Gly886 leaves the subpocket widely open and fully accessible. Thr854 and Tyr858 of helix H14 and Leu883 and Gly886 of helix H15 form two walls of the pocket, while the fragment around Asn881 of the M-loop constitutes the third side of the pocket (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, the bottom of the subpocket is open to the molecular surface of LmjPDEB1. Thus, the pocket looks more like an open channel. It has a size capable of accommodating a five-membered ring and shows mixed hydrophilic and hydrophobic characteristics. Since this subpocket is unique for LmjPDEB1, we tentatively name it as leishmania pocket or L-pocket for short, and we believe that it is useful for the development of Leishmania-selective inhibitors.

Concluding remarks

The crystal structure of LmjPDEB1 shares a common topological folding with human PDEs. However, the active site of LmjPDEB1 shows subtle but significant differences from those of human PDEs, implying the feasibility to develop LmjPDE selective inhibitors. Most surprising, the L-pocket that neighbors the active site appears to be unique to the parasite LmjPDEB1, thus representing a candidate pocket for the design of LmjPDE selective inhibitors. The study in this paper reveals for the first time the structural information on a pathogen PDE, and therefore provides a template for the design of novel drugs for the treatment of leishmaniasis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein expression and purification of the catalytic domain of LmjPDEB1

The cDNA of the catalytic domain of Leishmania major PDEB1 corresponding to amino acids 582-940 was amplified by PCR and subcloned into the expression vector pET28a. The resulting plasmid pET-PDEB1 was transferred into E. coli strain BL21 (CodonPlus) for overexpression. When E. coli cell carrying pET-PDEB1 was grown in LB medium at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.7, 0.1 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside was added and the culture was further grown at 15°C for 24 hours. Recombinant PDEB1 was purified by Ni-NTA chromatography (Qiagen), subjected to thrombin cleavage, and further purified by ion-exchange chromatography on QSepharose and gel filtration on Sephacryl S300 (Amersham Biosciences). A typical purification yielded about 10 mg LmjPDEB1 with a purity of >95% from a 2-liter cell culture.

Protein crystallization and structure determination

The co-crystal of LmjPDEB1 (582-940) in complex with IBMX was grown by vapor diffusion. The LmjPDEB1-IBMX complex was prepared by mixing 2 mM IBMX with 15 mg/ml LmjPDEB1 that was stored in a buffer of 20 mM Tris.HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol. The protein drop was prepared by mixing 2 μl of the LmjPDEB1-IBMX complex with 2 μl well buffer of 30% PEG3350, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5 at 4°C. LmjPDEB1-IBMX was crystallized in the space group P21 with cell dimensions of a = 63.8, b = 78.8, c = 70.6 Å, and β = 92.5° (Table 1). The diffraction data were collected on beamline X29 at Brookhaven National Laboratory and processed by program HKL (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997).

Table 1.

Statistics on diffraction data and structure refinement

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P21 |

| Unit cell (a, b, c, Å) | 63.8, 78.7, 70.5, 90.0 92.5, 90.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.55 |

| Unique reflections | 100,381 |

| Fold of redundancy | 6.7 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.5† (68.9)* |

| Average I/σ | 14.0 (3.4)* |

| Rmerge | 0.054 (0.22)* |

| Structure Refinement | |

| R-factor | 0.190 |

| R-free | 0.208 (10%)‡ |

| Reflections | 98144 |

| RMS deviation for Bond (Å) | 0.0043 |

| Angle | 1.1° |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | |

| Protein | 22.7 (5322)§ |

| IBMX | 43.1 (32)§ |

| Waters | 31.5 (501)§ |

| Zn | 17.0 (2) |

| Mg | 15.1 (2) |

The 99.5% completeness is calculated by including 4312 reflections in resolution shell 1.55 to 1.50 Å.

The numbers in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

The percentage of reflections omitted for calculation of R-free.

The number of atoms in the crystallographic asymmetric unit.

The structure of LmjPDEB1-IBMX was solved by the molecular replacement program AMoRe (Navaza and Saludjian, 1997), taking the PDE7A1-IBMX structure without IBMX as the initial model. The atomic model was rebuilt by program O (Jones et al., 1991) against the electron density map that was improved by the density modification package of CCP4. The structure was refined by CNS (Table 1, Brünger et al., 1998).

Assay of enzymatic activity

The catalytic domain of LmjPDEB1 was incubated with a reaction mixture containing 20 mM Tris.HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1mM DTT, 3H-cAMP or 3H-cGMP (20000 cpm/assay) at room temperature for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by addition of 0.2 M ZnSO4 and 0.2 M Ba(OH)2. The reaction product 3H-AMP or 3H-GMP was precipitated by BaSO4 while the unreacted substrates remained in the supernatant. Radioactivity in the supernatant was measured by liquid scintillation counting. The activity was measured at eight concentrations of substrate. All assays were done in triplicate. For the measurement of IC50, twelve concentrations of inhibitors were used, with a substrate concentration less than one tenth of Km and a suitable enzyme concentration. The IC50 value is defined as the concentration of inhibitors where 50% of the enzyme activity is inhibited. The kinetic parameters Km and kcat were obtained following the theory of steady state kinetics.

Acknowledgements

We thank beamline X29 at NSLS for collection of the diffraction data. This work was supported by NIH grant GM59791 to HK, a grant from Otsuka Maryland Medicinal Laboratories and grant Nr 3100A0-109245 of the Swiss National Science Foundation to TS, and COST program B22 of the European Union.

Footnotes

Accession codes. The coordinates and structural factors have been deposited into the RCSB Protein Data Bank with accession code of 2R8Q.

References

- Ashutosh SS, Goyal N. Molecular mechanisms of antimony resistance in Leishmania. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007;56:143–153. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46841-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender AT, Beavo JA. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular regulation to clinical use. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58:488–520. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokland A, Schreiber R, Prickaerts J. Improving memory: a role for phosphodiesterases. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:2511–2523. doi: 10.2174/138161206777698855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography and NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Cryst. 1998;D54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro A, Jerez MJ, Gil C, Martinez A. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases and their role in immunomodulatory responses: advances in the development of specific phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Med. Res. Rev. 2005;25:229–244. doi: 10.1002/med.20020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti M, Beavo J. Biochemistry and physiology of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: Essential components in cyclic nucleotide signaling. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:481–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060305.150444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft SL, Seifert K, Yardley V. Current scenario of drug development for leishmaniasis. Indian J. Med. Res. 2006;123:399–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjeux P, Alvar J. Leishmania/HIV co-infections: epidemiology in Europe. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2003;97:S3–S15. doi: 10.1179/000349803225002499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galie N, Ghofrani HA, Torbicki A, Barst RJ, Rubin LJ, Badesch D, Fleming T, Parpia T, Burgess G, Branzi A, Grimminger F, Kurzyna M, Simonneau G. Sildenafil, Use in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (SUPER) Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:2148–2157. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houslay MD, Schafer P, Zhang KY. Keynote review: phosphodiesterase-4 as a therapeutic target. Drug Discov. Today. 2005;10:1503–1519. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huai Q, Liu Y, Francis SH, Corbin JD, Ke H. Crystal structures of phosphodiesterases 4 and 5 in complex with inhibitor IBMX suggest a conformation determinant of inhibitor selectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004a;279:13095–13101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huai Q, Wang H, Zhang W, Colman R, Robinson H, Ke H. Crystal structure of phosphodiesterase 9 shows orientation variation of inhibitor 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004b;101:9624–9629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401120101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iffland A, Kohls D, Low S, Luan J, Zhang Y, Kothe M, Cao Q, Kamath AV, Ding YH, Ellenberger T. Structural determinants for inhibitor specificity and selectivity in PDE2A using the wheat germ in vitro translation system. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8312–8325. doi: 10.1021/bi047313h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johner A, Kunz S, Linder M, Shakur Y, Seebeck T. Cyclic nucleotide specific phosphodiesterases of Leishmania major. BMC Microbiol. 2006;6:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Zou J-Y, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Cryst. 1991;A47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamhawi S. Phlebotomine sand flies and Leishmania parasites: friends or foes? Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke H, Wang H. Crystal structures of phosphodiesterases and implications on substrate specificity and inhibitor selectivity. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2007;7:391–403. doi: 10.2174/156802607779941242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedzierski L, Zhu Y, Handman E. Leishmania vaccines: progress and problems. Parasitology. 2006;133:S87–112. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006001831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz S, Beavo JA, D'Angelo MA, Flawia MM, Francis SH, Johner A, Laxman S, Oberholzer M, Rascon A, Shakur Y, Wentzinger L, Zoraghi R, Seebeck T. Cyclic nucleotide specific phosphodiesterases of the kinetoplastida: a unified nomenclature. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2005;145:133–135. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxman S, Rascon A, Beavo JA. Trypanosome cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 2B binds cAMP through its GAF-A domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:3771–3779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408111200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner A, Epstein PM. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases as targets for treatment of haematological malignancies. Biochem. J. 2006;393:21–41. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipworth BJ. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2005;365:167–175. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17708-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiseau PM, Bories C. Mechanisms of drug action and drug resistance in Leishmania as basis for therapeutic target identification and design of antileishmanial modulators. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2006;6:539–550. doi: 10.2174/156802606776743165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugnier C. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase (PDE) superfamily: a new target for the development of specific therapeutic agents. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;109:366–398. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menniti FS, Faraci WS, Schmidt CJ. Phosphodiesterases in the CNS: targets for drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:660–670. doi: 10.1038/nrd2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra J, Saxena A, Singh S. Chemotherapy of leishmaniasis: past, present and future. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007;14:1153–1169. doi: 10.2174/092986707780362862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaza J, Saludjian P. AMoRe: an automated molecular replacement program package. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:581–594. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omori K, Kotera J. Overview of PDEs and their regulation. Circ. Res. 2007;100:309–327. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000256354.95791.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascon A, Viloria ME, De-Chiara L, Dubra ME. Characterization of cyclic AMP phosphodiesterases in Leishmania mexicana and purification of a soluble form. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2000;106:283–292. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00224-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reithinger R, Dujardin JC. Molecular diagnosis of leishmaniasis: current status and future applications. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:21–25. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotella DP. Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors: current status and potential applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002;1:674–682. doi: 10.1038/nrd893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peluso MR. Flavonoids attenuate cardiovascular disease, inhibit phosphodiesterase, and modulate lipid homeostasis in adipose tissue and liver. Exp. Biol. Med. 2006;231:1287–1299. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem MM, Werbovetz KA. Natural products from plants as drug candidates and lead compounds against leishmaniasis and trypanosomiasis. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006;13:2571–2598. doi: 10.2174/092986706778201611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scapin G, Patel SB, Chung C, Varnerin JP, Edmondson SD, Mastracchio A, Parmee ER, Singh SB, Becker JW, Van der Ploeg LH, Tota MR. Crystal structure of human phosphodiesterase 3B: atomic basis for substrate and inhibitor specificity. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6091–6100. doi: 10.1021/bi049868i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz E, Hatz C, Blum J. New world cutaneous leishmaniasis in travellers. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:342–349. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70492-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Liu Y, Chen Y, Robinson H, Ke H. Multiple elements jointly determine inhibitor selectivity of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases 4 and 7. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:30949–30955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Liu Y, Huai Q, Cai J, Zoraghi R, Francis SH, Corbin JD, Robinson H, Xin Z, Lin G, Ke. H. Multiple conformations of phosphodiesterase-5: implications for enzyme function and drug development. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:21469–21479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Liu Y, Hou J, Zheng M, Robinson H, Ke H. Structural insight into substrate specificity of phospodiesterase 10. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., USA. 2007;104:5782–5787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700279104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu RX, Hassell AM, Vanderwall D, Lambert MH, Holmes WD, Luther MA, Rocque WJ, Milburn MV, Zhao Y, Ke H, Nolte RT. Atomic structure of PDE4: Insight into phosphodiesterase mechanism and specificity. Science. 2000;288:1822–1825. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang KY, Card GL, Suzuki Y, Artis DR, Fong D, Gillette S, Hsieh D, Neiman J, West BL, Zhang C, Milbum MV, Kim SH, Schlessinger J, Bollag G. A glutamine switch mechanism for nucleotide selectivity by phosphodiesterases. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]