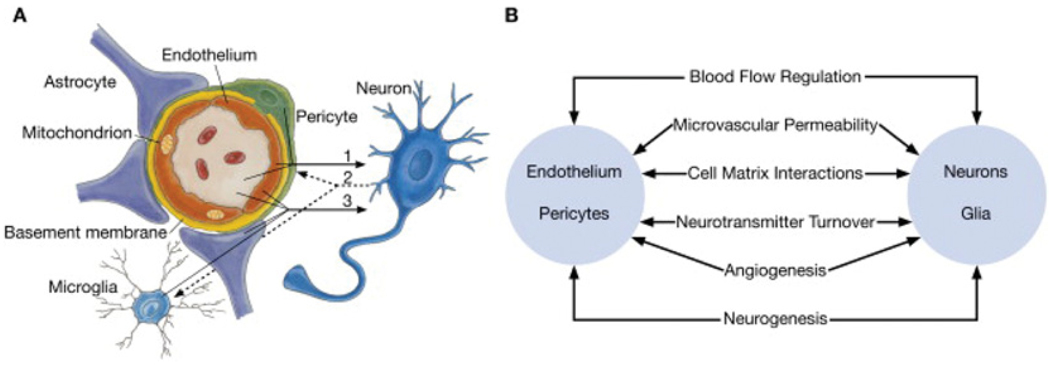

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the neurovascular unit.

(A) Endothelial cells and pericytes are separated by the basement membrane. Pericyte processes sheathe most of the outer side of the basement membrane. At points of contact, pericytes communicate directly with endothelial cells through the synapse-like peg-socket contacts. Astrocytic endfoot processes unsheathe the microvessel wall, which is made up of endothelial cells and pericytes. Resting microglia have a ‘ramified’ shape. In cases of neuronal disorders that have a primary vascular origin, circulating neurotoxins may cross the BBB to reach their neuronal targets, or pro-inflammatory signals from the vascular cells or reduced capillary blood flow may disrupt normal synaptic transmission and trigger neuronal injury (arrow 1). Microglia recruited from the blood or within the brain and the vessel wall can sense signals from neurons (arrow 2). Activated endothelium, microglia and astrocytes signal back to neurons, which in most cases aggravates the neuronal injury (arrow 3). In the case of a primary neuronal disorder, signals from neurons are sent to the vascular cells and microglia (arrow 2), which activate the vasculo–glial unit and contributes to the progression of the disease (arrow 3). (B) Co-ordinated regulation of normal neurovascular functions depends on vascular cells (endothelium and pericytes), neurons and astrocytes. Reprinted from Neuron volume 57, Zlokovic, B.V., The blood–brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders, pp. 178–201, Copyright (2008), with permission from Elsevier (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/08966273).