Abstract

Background

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is characterized by clinical features similar to those of acute myocardial ischemia, but without angiographic evidence of obstructive coronary artery disease. We present a patient with takotsubo cardiomyopathy following acute infarction involving the left insular cortex.

Case Report

A 52-year-old man was admitted with acute infarction of the left middle cerebral artery territory and acute chest pain. Acute myocardial infarction was suspected because of elevated serum troponin levels and hypokinesia of the left ventricle on echocardiography. However, a subsequent coronary angiography revealed no stenosis within the coronary arteries or ballooning of the apical left ventricle.

Conclusions

We postulated that catecholamine imbalance due to the insular lesion could be responsible for these interesting features.

Keywords: takotsubo cardiomyopathy, insula, infarction

Introduction

Transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome, also known as takotsubo cardiomyopathy, is an emerging disease entity that mimics acute myocardial infarction. This syndrome is characterized by the clinical features of acute chest pain and dyskinesia of the left ventricular apical or midventricular segment on echocardiography, but there is no angiographic evidence of obstructive coronary artery disease.1 We present a patient with takotsubo cardiomyopathy following acute infarction of the left insular cortex.

Case Report

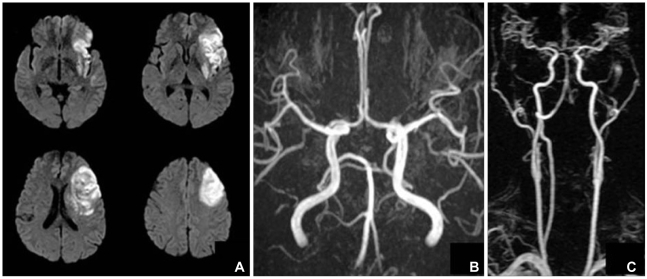

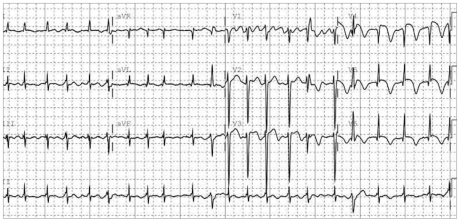

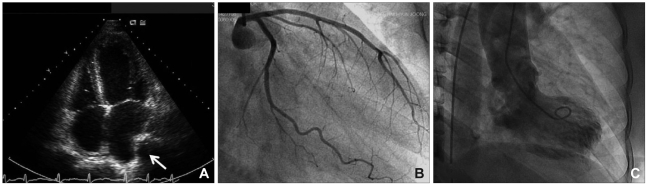

A 52-year-old man was transferred to the emergency room presenting with decreased mentality, chest pain, speech disturbance, and right hemiparesis. His medical history was unremarkable except for a 30-pack-year history of current smoking. His initial blood pressure and heart rate were 132/100 mmHg and 78 bpm, respectively. Phonemic paraphasia, left gaze preponderance, and right hemiparesis were noted on neurological examination. Diffusion weighted magnetic resonance (MR) imaging revealed a hyperintense lesion over the left frontoparietal lobe including the insular cortex, and MR angiography revealed no significant stenosis in the relevant arteries (Fig. 1). On admission, the patient complained of anterior chest pain and an irregular heart rate (110-140 bpm). Levels of the myocardial enzyme levels creatine phosphokinase and troponin I were increased to 424 U/l (normal range 58-348 U/l) and 12.09 ng/mL (normal range 0-2 ng/mL), respectively. Electrocardiography (ECG) revealed atrial fibrillation and ST-segment elevation at leads I, aVL, and V2-5, suggesting anterolateral wall ischemia (Fig. 2). Emergent transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated hypokinesia of the middle and apical walls of the left ventricle (LV) and an ejection fraction of 36% (Fig. 3A). We concluded that the patient had experienced an acute myocardial infarction with new onset atrial fibrillation and cardioembolic stroke. Digitalization and heparinization were commenced. However, subsequent coronary angiography did not disclose any stenosis within the coronary arteries (Fig. 3B). Left ventriculography revealed severe hypokinesia of the anterolateral and apical walls of the LV with vigorous contraction of the basal segment, mimicking a takotsubo, a round-bottomed, narrow-necked Japanese fishing pot used for trapping octopus (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 1.

Brain magnetic resonance image and angiography of the patient. A: Acute infarction of the middle cerebral artery territory involving the left insular cortex. B and C: No significant stenosis was noted in relevant arteries on magnetic resonance angiography.

Fig. 2.

Electrocardiography showing atrial fibrillation with ST-segment elevation at leads I, aVL, and V2-5, suggesting acute anterolateral wall ischemia.

Fig. 3.

Echocardiography showing hypokinesia of the middle and apical walls of the left ventricle (A); no stenotic lesion was found on coronary angiography (B). Note the characteristic appearance of "apical ballooning" on the left ventriculogram (C), which is similar to that of a takotsubo, a Japanese octopus-trapping pot.

The patient's condition had improved with the cardiac enzyme levels having declined to within the normal range by 4 days after the initial event. A follow-up echocardiography performed 6 days after the attack demonstrated improved wall motion of the apical LV. ECG performed on the same day showed T wave inversion and QTc prolongation at the anterolateral leads. The patient was discharged 2 weeks after the initial event after achieving an International Normalized Ratio within the therapeutic range.

Discussion

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a rare syndrome that mimics acute myocardial infarction with chest pain, dyspnea, electrocardiographic ST-segment changes, elevated troponin, and left ventricular dysfunction. Cardiac catheterization should reveal a typical left ventricular wall motion pattern without any sign of coronary heart disease. A hypokinetic apical segment and hyperkinetic basal segment, which looks like a takotsubo, is observed on end-systolic ventriculography.1

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is observed in 0.7-2.5% of patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome, affecting postmenopausal women in most cases.1,2 Although the exact mechanism underlying this pathology is not clear, reduced estrogen levels seem to cause endothelial dysfunction or changes in catecholamine metabolism.2

The prognosis seems to be favorable and recurrence occurs in <10% of patients.2 The common complication is left-heart failure, left ventricular intracavitary obstruction, and arrhythmia.1 In extreme and neglected cases it can lead to sudden and unexpected death.

The etiology of this syndrome is still unclear, but catecholamine-mediated neurogenic myocardial stunning has been proposed,3 given that physical or emotional stress usually provokes this syndrome.4,5 Some medicolegal problems associated with any procedure-related cardiac complication is suspected with this emotional or physical stress-induced cardiomyopathy.

Serum catecholamine levels are elevated, even beyond those of patients with acute myocardial infarction6 and abnormal sympathetic nerve function, as shown by single-photon-emission computed tomography using 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine, a radioiodinated analog of norepinephrine.7 No consensus or guideline for treatment exists; however, beta-blocker administration can be helpful, given that emotional-stress-induced apical LV ballooning was normalized by pretreatment with adrenoreceptor blockade.8

Our patient had chest pain on admission, which indicates takotsubo cardiomyopathy preceding ischemic infarction as a possible scenario. However, this patient had no other underlying cardiac or systemic disease or stressful emotional event that could have caused left ventricular dysfunction. In addition, atrial fibrillation had resolved by the follow-up ECG and cardiac wall motion had improved, suggesting a condition of a transient rather than a permanent nature. Therefore, we postulate that autonomic imbalance secondary to infarction involving the insular cortex might have caused the transient left ventricular dysfunction observed in this patient.

Whilst cardiac abnormalities including takotsubo cardiomyopathy have been reported in cases of all types of massive ischemic stroke, the insular cortex has attracted the attention of physicians. The reason for this is that the viscerotopic sensory area of the insular cortex is a convergent center that receives input from the limbic and autonomic systems in the brain.9 Lesion or stimulation of the insular cortex causes various cardiovascular responses, including changes in blood pressure, QT dispersion, T wave inversion, and elevated troponin levels.10-13

Sympathetically mediated takotsubo-like syndrome has been reported in a few cases of subarachnoid hemorrhage.14,15 However, takotsubo cardiomyopathy following cerebral infarction has been reported only rarely. The mechanism underlying the pathology of each case might be different.15 In addition, neurologists tend to assign a chest pain in recent stroke patients to concurrent acute myocardial ischemia.

Cardiac autonomic dysfunction in various neurological and medical conditions has not attracted the neurologists' attention. We believe that research into and treatment of these dysfunctions by neurologists is necessary, because the human cardiac organ is simple and regulated only by the nervous system. More precise studies of the neural regulation of cardiac function would elucidate the underlying pathophysiologic mechanism of this enigmatic syndrome, enabling the development of a therapeutic regimen.

Acknowledgements

The work described in this paper was supported by Konkuk University in 2006.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pilgrim TM, Wyss TR. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome: A systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2008;124:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prasad A, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Apical ballooning syndrome (Tako-Tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): a mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2008;155:408–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kume T, Kawamoto T, Okura H, Toyota E, Neishi Y, Watanabe N, et al. Local release of catecholamines from the hearts of patients with tako-tsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction. Circ J. 2008;72:106–108. doi: 10.1253/circj.72.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bybee KA, Prasad A, Barsness GW, Lerman A, Jaffe AS, Murphy JG, et al. Clinical characteristics and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction frame counts in women with transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:343–346. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parodi G, Del Pace S, Carrabba N, Salvadori C, Memisha G, Simonetti I, et al. Incidence, clinical findings, and outcome of women with left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:182–185. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, Baughman KL, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:539–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akashi YJ, Nakazawa K, Sakakibara M, Miyake F, Musha H, Sasaka K. 123I-MIBG myocardial scintigraphy in patients with "takotsubo" cardiomyopathy. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1121–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ueyama T, Kasamatsu K, Hano T, Yamamoto K, Tsuruo Y, Nishio I. Emotional stress induces transient left ventricular hypocontraction in the rat via activation of cardiac adrenoceptors: a possible animal model of 'tako-tsubo' cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2002;66:712–713. doi: 10.1253/circj.66.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eickhoff SB, Lotze M, Wietek B, Amunts K, Enck P, Zilles K. Segregation of visceral and somatosensory afferents: an fMRI and cytoarchitectonic mapping study. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1004–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colivicchi F, Bassi A, Santini M, Caltagirone C. Cardiac autonomic derangement and arrhythmias in right-sided stroke with insular involvement. Stroke. 2004;35:2094–2098. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000138452.81003.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ay H, Koroshetz WJ, Benner T, Vangel MG, Melinosky C, Arsava EM, et al. Neuroanatomic correlates of stroke-related myocardial injury. Neurology. 2006;66:1325–1329. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000206077.13705.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagaev V, Aleksandrov V. Visceral-related area in the rat insular cortex. Auton Neurosci. 2006;125:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheshire WP, Jr, Saper CB. The insular cortex and cardiac response to stroke. Neurology. 2006;66:1296–1297. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219563.87204.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banki NM, Kopelnik A, Dae MW, Miss J, Tung P, Lawton MT, et al. Acute neurocardiogenic injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Circulation. 2005;112:3314–3319. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.558239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayer SA, Lin J, Homma S, Solomon RA, Lennihan L, Sherman D, et al. Myocardial injury and left ventricular performance after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1999;30:780–786. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.4.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]