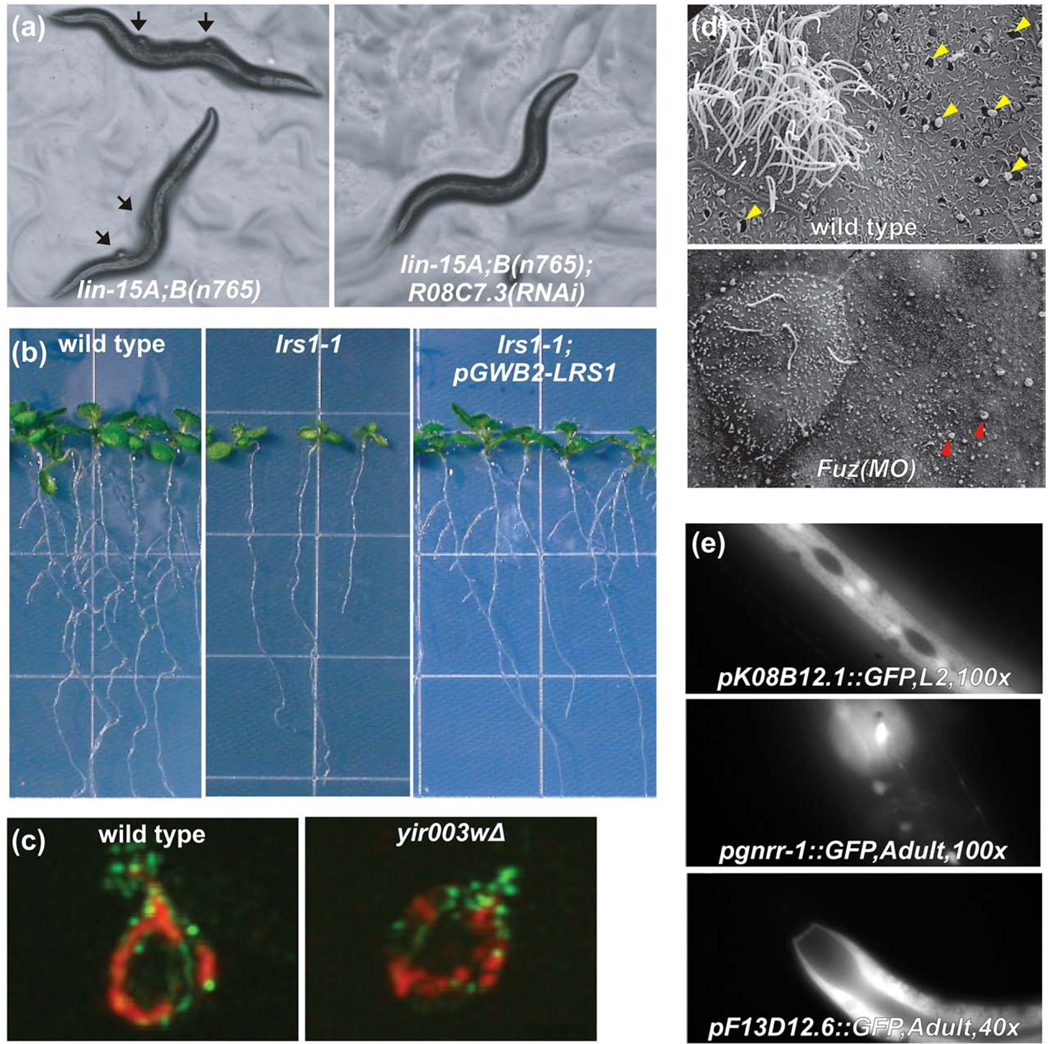

Fig. 5.

Examples of experimentally validated network-guided predictions of genes underlying specific traits in yeast, plants, and animals. (a) The lin-15A;B(n765) strain of C. elegans has inactivated synMuv A and synMuv B retinoblastoma tumor suppressor pathways, causing a synthetic multivulval phenotype, in which altered cell fate specification causes normally epithelial cells to adopt a vulval cell fate, creating ectopic vulvae that are a C. elegans model for tumor formation [105]. RNAi against genes that antagonize the pathways, such as R08C7.3, suppress the phenotype, as predicted by network guilt-by-association. Figure adapted with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: [26], 2008. (b) When the Arabidopsis gene lrs1-1 is disrupted by a T-DNA insertion, the number of lateral roots is strongly reduced (middle panel) compared to wild-type plants (left panel). Reintroduction of the functional gene as a transgene restores wild-type phenotype (right panel), confirming a role in root development predicted from an Arabidopsis gene network. Figure adapted with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: [38], 2010. (c) A confirmed roles for candidate yeast protein YIR003W in mitochondrial biogenesis, predicted using computational methods from proteomics and genomics datasets, can be seen reflected in mitochondrial motility defects in a YIR003W deletion strain, measured by dual channel immunofluorescence of mitochondria (red) and actin (green) (adapted from ref. [81]). (d) A mouse protein network [48] and results of large-scale computational predictions of mouse protein function [62] suggested a role for the birth-defect relevant gene Fuz in vesicle trafficking and biogenesis of cilia that was confirmed by knockdown in developing Xenopus embryos [89]. The top panel shows a wild-type multiciliated cell flanked by secretory cells in X. laevis. Note the exocytotic pits indicated by the yellow arrowheads. Fuz morphants show ciliogenesis defects as well as failure of exocytosis in secretory cells (bottom); note the apical membrane blebs indicated by green arrowheads. Figure adapted with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: [89], 2009. (e) Using GFP-reporter constructs, C. elegans gene network-predicted tissue-specific gene expression was verified in the hypodermis, intestine, hypodermis, neurons, and muscle of worms by Chikina et al. (adapted from Ref. [82]).