Abstract

Stroke is a leading cause of mortality and long-term morbidity. As a means for stroke prevention, an estimated 99,000 carotid endarterectomy procedures were performed in the USA in 2006. Traditionally, the degree of luminal stenosis has been used as a marker of the stage of atherosclerosis and as an indication for surgical intervention. However, prospective clinical trials have shown that the majority of patients with a history of recent transient ischemic attack or stroke have mild-to-moderate carotid stenosis. Using stenosis criteria, many of these symptomatic individuals would be considered to have early-stage carotid atherosclerosis. It is evident that improved criteria are needed for identifying the high-risk carotid plaque across a range of stenoses. Histological studies have led to the hypothesis that plaques with larger lipid-rich necrotic cores, thin fibrous cap rupture, intraplaque hemorrhage, plaque neovasculature and vessel wall inflammation are characteristics of the high-risk, ‘vulnerable plaque’. Despite the widespread consensus on the importance of these plaque features, testing the vulnerable plaque hypothesis in prospective clinical studies has been hindered by the lack of reliable imaging tools for in vivo plaque characterization. MRI has been shown to accurately identify key carotid plaque features, including the fibrous cap, lipid-rich necrotic core, intraplaque hemorrhage, neovasculature and vascular wall inflammation. Thus, MRI is a histologically validated technique that will permit prospective testing of the vulnerable plaque hypothesis. This article will provide a summary of the histological validation of carotid MRI, and highlight its application in prospective clinical studies aimed at early identification of the high-risk atherosclerotic carotid plaque.

Keywords: carotid atherosclerosis, early-stage atherosclerosis, high-risk plaque, MRI, stroke, vulnerable plaque

Stroke is the leading cause of long-term disability as well as the third most common cause of mortality in the USA. Approximately 795,000 individuals experience a new or recurrent stroke each year in the USA, that is one person every 40 s [1]. The estimated direct and indirect cost of stroke for 2009 is US$68.9 billion [1], and the projected costs for 2050 exceed $2.2 trillion, leading to a call for a greater focus on stroke prevention and improvement in the treatment of patients with acute stroke [2].

A number of randomized trials have documented the clinical benefit of carotid endarterectomy (CEA) for secondary stroke prevention among recently symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis [3-5]. In the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET), patients with carotid atherosclerosis who had a recent history of transient ischemic attack (TIA) or nondisabling stroke were randomized to optimal medical therapy or CEA. In the subgroup with 70–99% stenosis, CEA was associated with an absolute risk reduction of 17% for ipsilateral stroke over 2 years [3].

The role of CEA in symptomatic patients with less than 70% carotid disease is less clear. In this more moderate stenosis group, CEA afforded an absolute risk reduction of only 6.5% for stroke over the following 5 years, compared with best medical therapy. As such, 15 CEA procedures would need to be performed to prevent one stroke over 5 years.

While results from NASCET and other prospective trials indicate a higher risk for stroke with severe carotid stenosis [6], it is noteworthy that the large majority of the subjects in these trials who presented with recent carotid territory ischemic events were found to have mild-to-moderate stenosis. The European Carotid Surgery Trial reported that 43.8% of the 3018 individuals with symptomatic carotid disease had less than 30% stenosis on angiography [7]. NASCET reported that 61% of the 2226 recently symptomatic subjects had less than 50% carotid stenosis [8]. Also of note, the risk for stroke in NASCET was similar amongst those with 50–69% stenosis (22.2% at 5 years) and those with 0–49% stenosis (18.7% at 5 years) [8]. These findings suggest that severity of carotid stenosis is a poor discriminator of stroke risk amongst those with mild-to-moderate luminal narrowing.

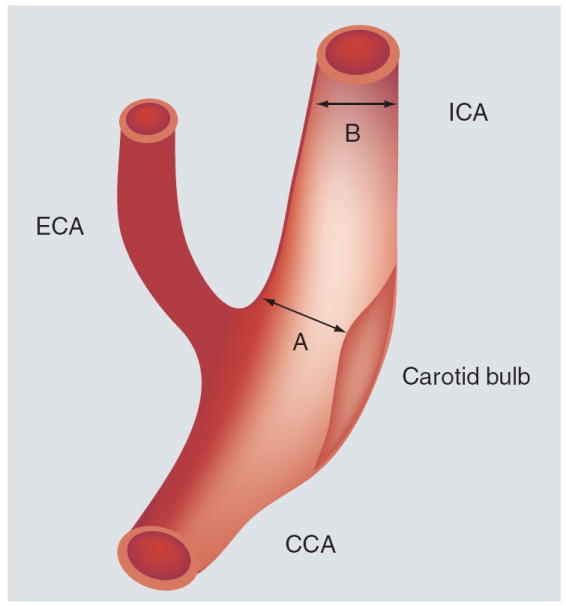

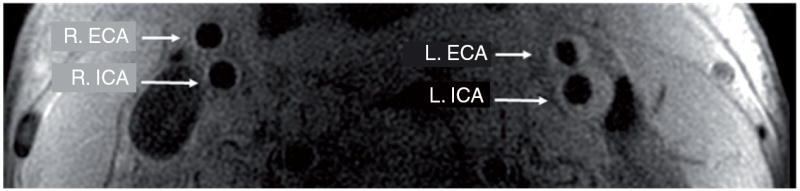

Based on these observations, additional criteria have been sought to better identify patients most at risk for complications from carotid atherosclerosis. Wasserman, Virmani and colleagues have advocated looking beyond luminal narrowing to identify the high-risk carotid plaque. They and others have shown that measurement of stenosis, using the method described in NASCET, underestimates plaque burden [9-11]. This is likely related to the geometry of the carotid bulb, which is normally larger than the more distal internal carotid artery (Figure 1), as well as the phenomenon of expansive remodeling, originally described by Glagov (Figure 2) [12]. Based on the geometry of the bulb, it is possible to have an eccentric plaque opposite the flow divider, despite measurement of a 0% stenosis, using the method described in NASCET (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Scheme demonstrating the typical geometry of the carotid bulb.

The percent stenosis, measured using the NASCET method = [1 – (A/B)] *100%.

CCA: Common carotid artery; ECA: External carotid artery; ICA: Internal carotid artery.

Figure 2. T1-weighted MRI of the carotid arteries just cephalad to the carotid bifurcation.

The R. ICA and R. ECA are normal. The L. ICA and L. ECA demonstrate evidence of expansive remodeling and eccentric plaque. Note that the lumen diameters in the R. ICA and L. ICA are the same.

ECA: External carotid artery; ICA: Internal carotid artery; L.: Left; R.: Right.

Beyond simple plaque burden, a number of investigators have hypothesized that specific compositional features of the plaque also distinguish the high-risk, ‘vulnerable plaque’ from the stable, clinically silent lesion. Analysis of histological findings in CEA specimens has shown that fibrous cap (FC) rupture, intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH), large lipid-rich necrotic cores, erosions with overlying mural thrombus, plaque neovasculature and inflammatory cell infiltration are more commonly observed in plaques removed from previously symptomatic patients [13-19].

In summary, findings from the symptomatic carotid clinical trials indicate that the majority of patients with recent carotid territory ischemic events have mild (<30%) to moderate (30–69%) carotid stenosis. Additional plaque parameters, other than quantification of stenosis, are needed to identify the high-risk plaque amongst these individuals who are presumed to have early-stage carotid atherosclerosis.

Role of imaging

Progress toward prospectively testing the ‘vulnerable plaque hypothesis’ has been hampered by the inability to accurately and reproducibly identify key plaque features that are believed to represent the high-risk lesion in vivo. Transcutaneous B-mode ultrasonography provides a relatively inexpensive method for imaging carotid plaque with high resolution. Studies dating back to the early 1980s have shown that plaques with an echolucent, heterogeneous or ulcerated appearance are associated with TIA or stroke [20-27]. Challenges for ultrasound include acoustical shadowing from calcification, anisotropic effects (where the appearance of the lesion can vary depending on the angle of insonation) [28-30], operator variability, lack of specificity for distinguishing lipid core from IPH and modest reader reproducibility [27,31-34]. CT and PET are promising modalities to quantify atherosclerotic carotid artery lesion size and compositional features, particularly calcification (CT) [35-39] and vessel wall inflammation (PET) [40-43]. Advantages of MRI include its superior specificity for characterizing tissue composition, image generation without ionizing radiation and extensive histological validation for characterizing carotid atherosclerosis. Multiple centers have shown that MRI can reliably identify FC status [44-48], plaque composition [49-58], neovasculature and vascular wall inflammation [59,60] using histology as the gold standard. This has been achieved via the development of custom designed surface coils that result in significant improvement in the signal-to-noise ratio, and specialized multicontrast-weighted imaging sequences that include bright-blood time-of-flight (TOF) as well as pre- and postgadolinium contrast-enhanced black-blood imaging, which provide submillimeter (~0.6 mm) in-plane resolution. Details of hardware development, pulse-sequence design and MRI criteria for carotid plaque characterization have been previously published [61-67].

Histological validation of MRI

FC status & lipid-rich necrotic core

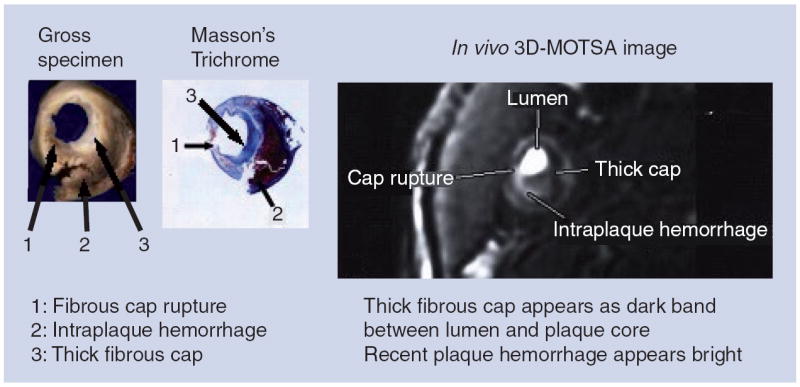

Using a multicontrast-weighted protocol including a 3D TOF bright-blood imaging technique, Yuan et al. described the MRI appearance of intact/thick FC as a continuous hypointense band near the bright lumen on 3D-TOF images, and a smooth luminal surface. Plaques where the hypointense band could not be visualized were categorized as having an intact/thin FC. FC rupture was identified by the absence or discontinuity of the hypointense band, juxtaluminal hyperintense signal in the TOF and T1-weighted (T1W) images (consistent with recent hemorrhage), and/or an irregular lumen surface. In a study comparing in vivo MRI with histology in patients scanned prior to CEA, Yuan found a high level of agreement between the magnetic resonance (MR) findings and the histological state of the FC, with a k value of 0.83 (95% CI: 0.67–1.0) and a weighted k value of 0.87 [44]. The sensitivity and specificity for identifying a thin or ruptured cap was 81 and 90%, respectively [45]. Figure 3 illustrates the appearance of the FC on 1.5 T MRI, and Figure 4 demonstrates FC rupture with ulceration and thrombus formation on 3 T MRI, with corresponding histology. Figure 5 demonstrates cap rupture with ulceration in the common carotid artery on 3 T MRI.

Figure 3. Appearance of the fibrous cap on MRI obtained prior to carotid endarterectomy, with matching gross and histological cross sections of the excised specimen.

Cap rupture is seen at the 8:00–9:00 position (arrow 1) on histology and MRI, with associated recent intraplaque hemorrhage (arrow 2). Adjacent thick cap is seen (arrow 3) as a dark band on magnetic resonance image. Reproduced with permission from [44].

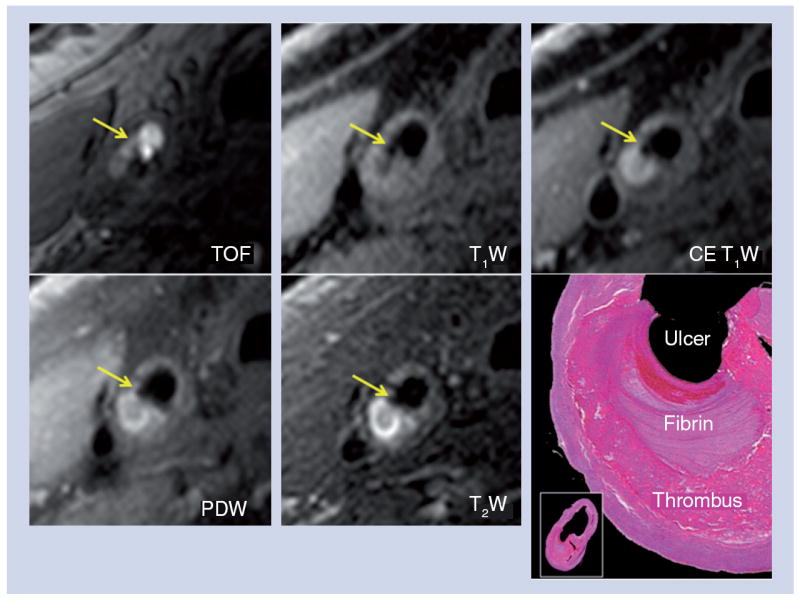

Figure 4. 3 T MRI of a plaque in the right common carotid artery that demonstrates fibrous cap rupture with ulcer formation (yellow arrow).

The crescent-shaped, high-signal region in the PDW, T2W and CE T1W images corresponds to a region of thrombus formation, shown on the matched histology section (hematoxylin and eosin stain).

CE: Contrast enhanced; PDW: Proton density weighted; T1W: T1-weighted; T2W: T2-weighted; TOF: Time-of-flight.

Reproduced with permission from [63].

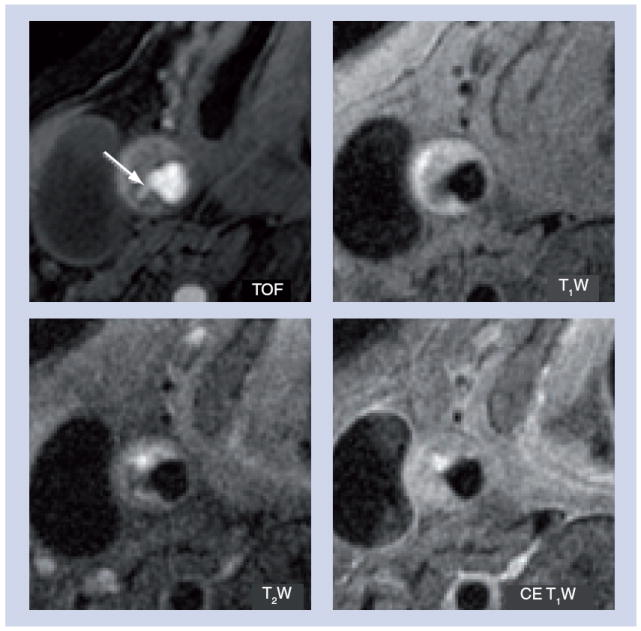

Figure 5. 3 T MRI of a plaque in the right common carotid artery with fibrous cap rupture with ulceration (arrow) on TOF, T1W, T2W, CE T1W images.

CE: Contrast enhanced; T1W: T1-weighted; T2W: T2-weighted; TOF: time-of-flight.

Reproduced with permission from [63].

A more recently published study by Cai et al. [48] demonstrated the utility of gadolinium-based contrast-enhanced MRI for increasing the conspicuity of the FC and the lipid-rich necrotic core (LRNC), permitting more reliable quantification of FC and LRNC dimensions. A total of 108 cross-sectional locations with intact FCs from 21 arteries were matched between MRI and the excised histology specimens. Quantitative measurements of FC length along the lumen circumference, FC area and LRNC area were collected from contrast-enhanced MR images and histology sections (Figure 6). Blinded comparison of corresponding MRI and histology slices showed moderate to good correlation for length (r = 0.73, p < 0.001) and area (r = 0.80, p < 0.001) of the intact FC. The mean percent LRNC areas ([LRNC area divided by the wall area] × 100%) measured by contrast-enhanced MRI and histology were 30.1 and 32.7%, respectively, and were strongly correlated across locations (r = 0.87, p < 0.001). Intraobserver reproducibility was excellent for LRNC area, FC area and FC length (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.87, 0.72 and 0.80, respectively). Interobserver reproducibility was also excellent for LRNC area, FC area and FC length (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.89, 0.78 and 0.81, respectively).

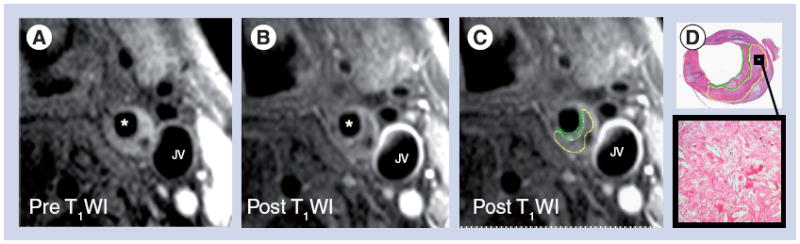

Figure 6. Improved conspicuity of the fibrous cap and lipid-rich necrotic core on postcontrast-enhanced MRI.

(A) Precontrast T1WI acquired at 1.5 T demonstrating a large eccentric plaque in the common carotid artery. (B) Postcontrast T1WI demonstrates differential enhancement of the fibrous cap and underlying lipid-rich necrotic core. (C) Measurement of the fibrous cap (green) and lipid-rich necrotic core (yellow) areas. (D) Matched histological cross-section of the common carotid artery from the excised specimen with fibrous cap (green) and necrotic core (yellow) outlined. Box demonstrates high-power view of the lipid-rich necrotic core demonstrating abundant cholesterol clefts.

*Lumen of common carotid artery.

JV: Jugular vein; T1WI: T1-weighted image.

Reproduced with permission from [48].

Juxtaluminal hemorrhage/mural thrombus

Intraplaque hemorrhage, deep within the core of the lesion, and hemorrhage/thrombus near or on the luminal surface may differ in etiology and clinical implications. In a study of 26 patients scheduled for CEA, Kampschulte et al. compared preoperative carotid MRI findings to the patients’ matched histology to determine whether MRI can distinguish between deep IPH and juxtaluminal hemorrhage/mural thrombus [55]. Hemorrhages were identified using previously established MRI criteria (type I = more recent hemorrhage: hyperintense on TOF and T1W images; type II = older hemorrhage: hyperintense on TOF, T1W, proton density-weighted and T2W images) [68] and their locations were differentiated between intraplaque and juxtaluminal. Corresponding histology was used to confirm the MR findings. Matched sections (n = 190) contained 144 areas of hemorrhage by histology, of which MRI correctly detected 132 areas. The sensitivity and specificity for MRI to correctly identify cross-sections containing hemorrhage was 96 and 82%, respectively. Furthermore, MRI was able to distinguish juxtaluminal hemorrhage/thrombus from IPH with an accuracy of 96%.

Moody and colleagues have shown that the contrast between plaque hemorrhage and other plaque components can be improved using an inversion-prepared rapid 3D gradient-echo sequence, also known as MP-RAGE (Figure 7) [51]. In a study of 63 patients who underwent an MRI scan prior to CEA, the authors reported a sensitivity and specificity of 84%, and very good reproducibility (inter- and intraobserver κ = 0.75 and 0.9, respectively).

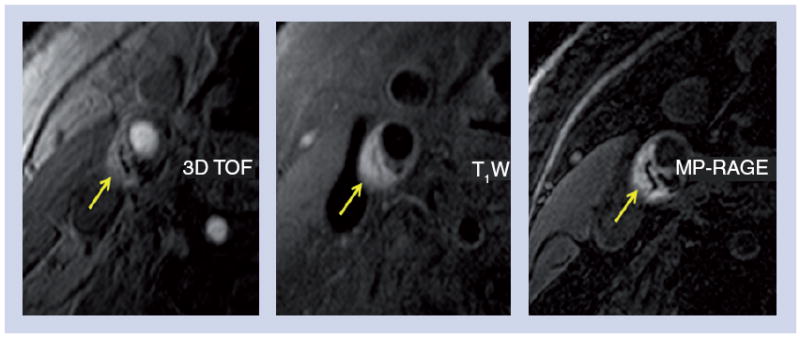

Figure 7. Characteristic appearance of intraplaque hemorrhage with hyperintense signal in the TOF, T1W and MP-RAGE images, acquired on a 3 T MRI scanner.

MP-RAGE: Magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient-echo;

T1W: T1-weighted; TOF: time-of-flight.

Reproduced with permission from [63].

Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, neovasculature & macrophage infiltration of plaque

In the 1930s, Winternitz reported that neovasculature may be involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis [69]. More recently, O’Brien noted that neovasculature within plaques may represent a pathway for the recruitment of macrophage infiltration, and that the endothelial cells lining these microvessels are a site of inflammatory activation [70]. Work by Galis, Libby and Nikkari have shown that macrophages, typically found in the shoulder regions adjacent to the FC, express matrix metalloproteinases that can result in the weakening of the FC, predisposing it to rupture [71-73]. More recently, Levy et al. have suggested that plaque neovasculature may play an important role in the pathogenesis of IPH [74].

Work by a number of investigators have demonstrated differential enhancement of carotid plaque tissues using gadolinium-based MRI contrast agents [50,75,76]. They found that strong enhancement generally suggests the presence of a highly permeable vascular supply within the plaque (neovasculature) and loose extracellular matrix for contrast agent uptake. As neovasculature and increased endothelial permeability are both associated with plaque inflammation [70,77-80], gadolinium enhancement of the vessel wall has been hypothesized to be a marker of the vascular wall inflammation. To probe this hypothesis further using quantitative analyses, Kerwin et al. used dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI to measure the rate of uptake of gadolinium-based contrast, characterized by the transfer constant Ktrans, and compared these measurements to histological measurements of plaque composition and inflammation. The parameter Ktrans is well known in oncology, where it has been used to characterize tumor blood supply and permeability [81].

To measure Ktrans, repeated MRI measurements were made over short intervals to observe the dynamics of enhancement in the tissue of interest and in a reference arterial lumen (the ‘arterial input function’). The arterial input function and tissue-enhancement curves were then fit by a parametric model of contrast agent kinetics. Kerwin utilized the equation:

where Ct, and Cp are the contrast agent concentrations in the tissue (total), and blood plasma, respectively, and υp is the partial volume of blood plasma. This is the standard kinetic model [82] with a vascular term and ignoring reflux. Concentrations were assumed to be proportional to intensity change. The results of this modeling are parametric maps of υp and Ktrans in the plaque that not only quantify the amount of enhancement, but also the rate of enhancement.

Using this dynamic MRI acquisition protocol, Kerwin measured υp and Ktrans in 30 patients scheduled to undergo CEA [60]. The excised specimens were then histologically analyzed to measure neovasculature and macrophage content, expressed as percent area (% neovasculature = [neovasculature area divided by plaque area] × 100%). Measurements of υp correlated with neovasculature content (Figure 8A; r = 0.68, p < 0.001). Ktrans also correlated with neovasculature (Figure 8B; r = 0.71, p < 0.001) and macrophage content (Figure 8C; r = 0.75, p < 0.001). Interestingly, there was a negative correlation between Ktrans and high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol levels (r = -0.66, p < 0.001). Ktrans was also noted to be significantly higher amongst cigarette smokers compared with nonsmokers (mean: 0.134 vs 0.074 min-1; p = 0.01). Both low HDL and smoking have been found to be proinflammatory stimuli for atherosclerosis [83,84].

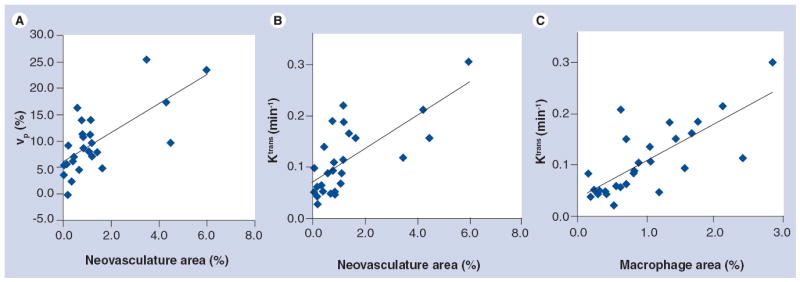

Figure 8. Correlation between plaque neovasculature, macrophage content and quantitative measures of plaque enhancement on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI.

(A) Scatter plots of vp measured using dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI versus histologic measurement of neovasculature content, expressed as percent neovasculature area ([neovasculature area divided by plaque area] × 100%). Pearson r = 0.68, p < 0.001. (B) Scatter plots of Ktrans versus histologic measurement of percent neovasculature area. Pearson r = 0.71, p < 0.001. (C) Scatter plots of Ktrans versus histologic measurement of macrophage content, expressed as percent macrophage area ([macrophage area divided by plaque area] × 100%). Pearson r = 0.75, p < 0.001.

vp: Portal volume of blood plasma.

Reproduced with permission from [60].

In summary, carotid MRI is a histologically validated tool that can identify the key features that are believed to characterize the vulnerable plaque, including FC status, plaque composition, neovasculature and vascular wall inflammation. Furthermore, MRI is ideally suited for serial assessment of temporal changes in the lesion in a noninvasive, nondestructive fashion. Therefore, MRI provides a critical tool to test the vulnerable plaque hypothesis in vivo.

Application of MRI in prospective clinical studies

Prospectively testing the vulnerable plaque hypothesis using carotid MRI

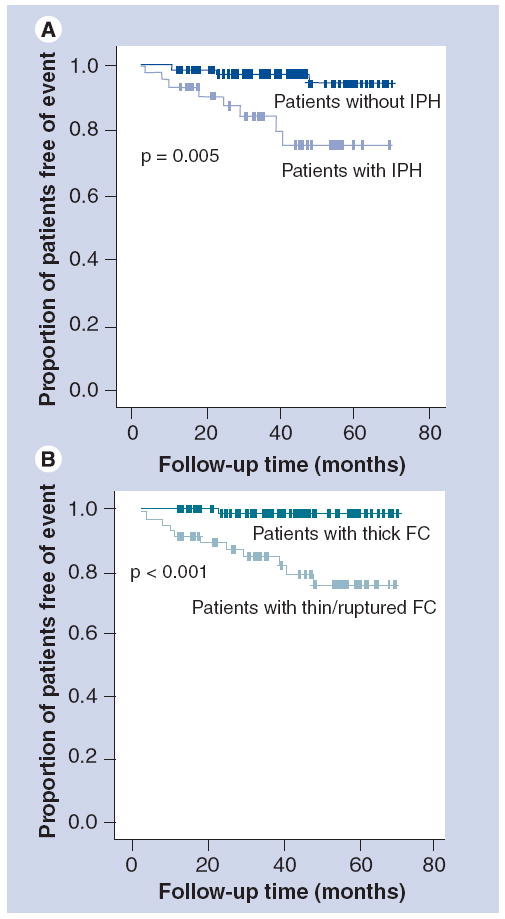

In a prospective, observational study of 154 subjects with 50–79% carotid stenosis who were asymptomatic at the time of enrollment, Takaya et al. tested the hypothesis that specific carotid plaque features are associated with a higher risk of subsequent TIA or stroke [85]. Following their baseline carotid MRI examination, subjects were called every 3 months to identify symptoms of new-onset TIA or stroke; 12 cerebrovascular events (four strokes and eight TIAs) that were judged to be carotid related occurred during a mean follow-up period of 38.2 months. Cox regression analysis demonstrated significant associations between ischemic events and presence of a thin or ruptured FC (hazard ratio: 17.0; p < 0.001), IPH (hazard ratio: 5.2; p = 0.005) and larger mean necrotic core area (hazard ratio for 10 mm2 increase: 1.6; p = 0.01) in the carotid plaque (Figure 9A & B).

Figure 9. Transient ischemic attack- and stroke-free survival amongst patients with carotid artery intraplaque hemorrhage and thin/ruptured fibrous cap.

(A) Kaplan–Meier survival estimates of the proportion of patients remaining free of ipsilateral TIA or stroke for subjects with (lower curve) and without (upper curve) IPH. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival estimates of the proportion of patients remaining free of ipsilateral TIA or stroke for subjects with (lower curve) and without (upper curve) thin or ruptured FC.

FC: Fibrous cap; IPH: Intraplaque hemorrhage; TIA: Transient ischemic attack.

Reproduced with permission from [85].

These findings were corroborated in a more recently published study by Singh et al [86]. A total of 91 initially asymptomatic men with 50–70% stenosis were followed for a mean period of 25 months. They reported that of the six cerebrovascular events that occurred, 100% corresponded to arteries with IPH present at baseline (hazard ratio: 3.6; p < 0.001) [86].

The value of MRI in patients who had a recent history of TIA or stroke and moderate carotid stenosis was recently demonstrated by Altaf et al. [87]. Amongst 64 subjects with 30–69% carotid stenosis and a recent carotid territory ischemic event, Altaf performed baseline carotid MRIs to identify IPH and followed the subjects for the development of subsequent TIA or stroke. Of all the index arteries demonstrated, 39 (61%) demonstrated IPH on baseline MRI. Median follow-up was 38 months. A total of 14 ipsilateral ischemic events (nine TIAs and five strokes) were observed during follow-up. Out of the 14 events, 13 occurred ipsilateral to carotid arteries with IPH (hazard ratio: 9.8; 95% CI: 1.3–75.1; p = 0.03).

The small number of ischemic events in these studies [85-87] precluded multivariate analyses. Nonetheless, these findings offer compelling prospective evidence of the potential of carotid MRI for defining the high-risk, vulnerable plaque, and provide a foundation for the design of larger, multicenter studies.

MRI predictors of rapid plaque burden & LRNC progression

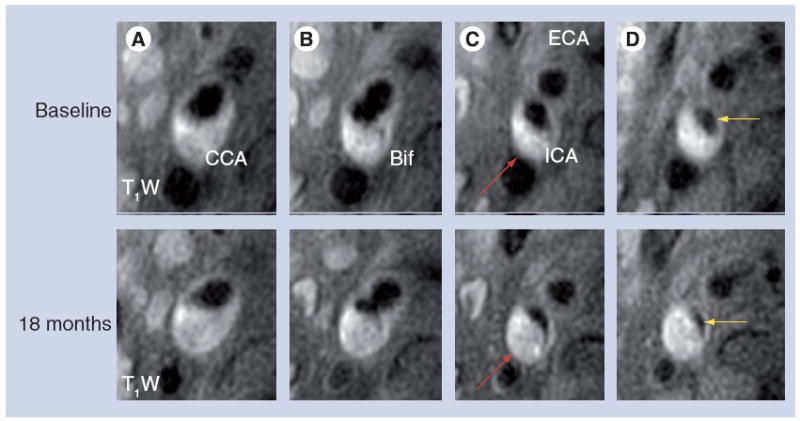

As a noninvasive imaging modality, MRI is ideally suited for serial examination of plaque features that may play a critical role in the pathogenesis of high-risk lesions of atherosclerosis. In a histopathology study of excised coronary arteries, Kolodgie, Virmani and colleagues suggested that IPH may represent a potent atherogenic stimulus by contributing to the deposition of free cholesterol, macrophage infiltration and enlargement of the necrotic core [88]. In a case–control study of 29 subjects participating in a longitudinal, serial MRI progression study, Takaya et al. tested the hypothesis that IPH, as detected by high-resolution MRI, was associated with greater progression in both necrotic core and plaque volume [89]. The volume of wall, lumen, necrotic core and IPH were measured at baseline and follow-up. Carotid arteries with IPH on baseline examination demonstrated markedly accelerated rates of progression in wall volume (6.8% with IPH vs -0.15% without IPH; p = 0.009) and LRNC volume (28.4% with IPH vs -5.2% without IPH; p = 0.001) over the course of 18 months (Figure 10). Furthermore, those with IPH at baseline were much more likely to have new plaque hemorrhages at 18 months compared with controls (43 vs 0%; p = 0.006). Findings from this study strongly suggest that hemorrhage into the carotid atherosclerotic plaque accelerates plaque progression within a relatively short period of 18 months.

Figure 10. T1-weighted magnetic resonance images of a patient with evidence of intraplaque hemorrhage at baseline.

The panels from left to right show cross-sectional images of (A) the CCA, (B) Bif, (C) proximal ICA and (D) the ICA more distally. The lower row shows the matched cross-sectional images on the 18-month follow-up MRI. There is marked decrease in luminal area (yellow arrows) in the internal carotid artery (C & D), and increase in atherosclerotic lesion size in the ICA (red arrows).

BiF: Carotid bifurcation; CCA: Common carotid artery; ECA: External carotid artery; ICA: Internal carotid artery; T1W: T1-weighted.

Reproduced with permission from [89].

Underhill et al. found a similar pattern in individuals with subclinical, earlier-stage carotid atherosclerosis [90]. In a prospective, longitudinal MRI study of 67 asymptomatic subjects with 16–49% stenosis, IPH was associated with accelerated progression in carotid wall volume compared with lesions without IPH (44.1 ± 36.1 vs 0.8 ± 34.5 mm3 per year; p < 0.001). Underhill also found that IPH altered the pattern of arterial remodeling. Lesions without IPH demonstrated outward, expansive remodeling with preservation of luminal dimension, as originally described by Glagov et al. [12]. However, in carotid arteries with IPH, these compensatory mechanisms appeared to be overridden by rapid expansion of the lesion, and was associated with luminal narrowing (-24.9 ± 21.1 mm3 per year; p = 0.002).

MRI predictors of luminal surface disruption

As noted earlier, MRI identification of FC rupture is highly associated with carotid territory ischemic events [85,91]. In a prospective, serial MRI study of 85 subjects with 50–79% stenosis and no luminal surface disruption at baseline, Underhill et al. examined the clinical and baseline carotid MRI plaque features that were associated with new FC disruption on follow-up MRI [92]. They found that the size of the LRNC at baseline was the strongest classifier for development of a new surface disruption at the 36 month follow-up scan (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.95). Presence of IPH was also a statistically significant, but weaker, classifier of new surface disruption (AUC = 0.73).

Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI & incident FC rupture

Oikawa et al. examined the relationship between the extent of adventitial vasa vasorum, as measured by Ktrans on baseline dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, and the development of new FC rupture at the 36 month follow-up [93]. Amongst 30 arteries evaluated, baseline mean Ktrans was significantly higher in arteries with FC rupture and/or IPH at baseline (n = 14) compared with those with intact surface without IPH (n = 16) (0.13 ± 0.005/min vs 0.10 ± 0.004/min, respectively; p < 0.001). Furthermore, amongst 23 arteries with an intact FC on the initial MRI, baseline mean Ktrans was significantly higher in arteries that developed MRI evidence of new FC rupture at 3 years (n = 4) compared with those with intact surface at follow-up (n = 19) (0.14 ± 0.009/min vs 0.10 ± 0.004/min, respectively; p = 0.004). A total of 50% of the arteries with a baseline mean Ktrans > 0.114/min developed FC rupture during follow-up (AUC = 0.91). These results suggest a potential role of adventitial neovasculature in the pathogenesis of plaque disruption. However, these preliminary findings require further investigation in larger studies.

Prevalence of high-risk plaque features in arteries with minimal-to-moderate stenosis

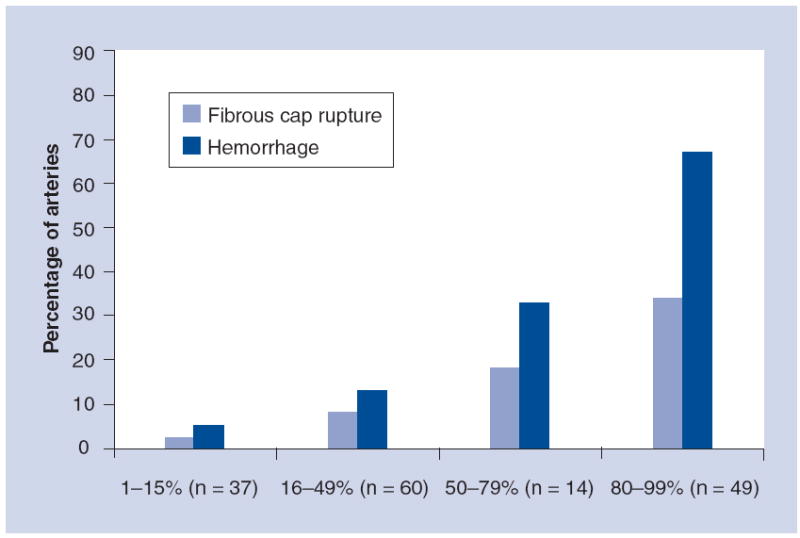

MRI studies have shown that presumptive high-risk plaque features, such as IPH and FC rupture, are commonly identified in carotid arteries with minimal-to-moderate stenosis [94,95]. In a review of 260 carotid MRI examinations performed in asymptomatic subjects, the prevalence of plaques with MRI evidence of IPH or FC rupture across a range of luminal stenoses was assessed by Saam et al. [94]. Up to a third of subjects with asymptomatic 50–79% stenosis and approximately 10% with 16–49% stenosis have evidence of cap rupture or IPH (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Prevalence of MRI identified fibrous cap rupture and intraplaque hemorrhage by degree of stenosis in carotid plaques (n = 260) of asymptomatic volunteers.

The degree of stenosis was determined by duplex ultrasound.

Adapted with permission from [94].

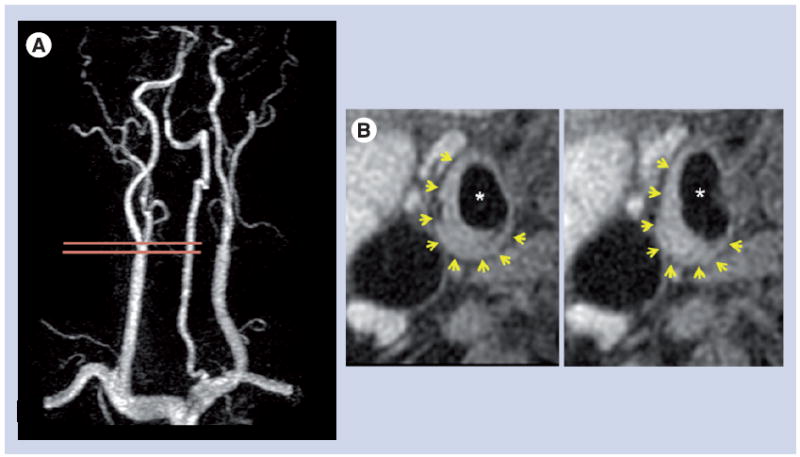

In a more recent study of subjects undergoing gadolinium contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (CE-MRA) and high-resolution carotid MRI at 3 T, Dong et al. found a surprisingly high prevalence of complex plaque features in arteries with 0% stenosis [96]. A total of 72 individuals with more than 50% carotid stenosis in at least one carotid artery by duplex ultrasonography were recruited for MRI of their bilateral carotid arteries. For each artery, the percent wall volume (wall volume/[lumen volume + wall volume] × 100%) and the prevalence of LRNC, calcification, IPH and FC rupture were recorded. Of the 144 arteries available for analysis, 133 had interpretable image quality, and 36.1% of the remaining arteries had a 0% stenosis on CE-MRA, as measured using NASCET criteria. Amongst arteries found to have a 0% stenosis by CE-MRA, the mean percent wall volume was 43.0 ± 6.9% with a range from 31.6 to 60.1%. LRNC was present in 67.4% (31 out of 46) of arteries, calcification was present in 65.2% (30 out of 46), IPH was present in 8.7% (4 out of 46), and FC rupture was present in 4.3% (2 out of 46). While selection criteria for the study limit extrapolation of these results to the general population, the findings confirm that angiography underestimates carotid plaque burden (Figure 12) [9,10] and is ineffective in detecting the presence of complex plaque.

Figure 12. Angiography underestimates carotid plaque burden.

(A) Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography demonstrates a right carotid artery with 0% stenosis. The two horizontal lines indicate the location of the cross-sectional black-blood magnetic resonance images (T1 weighted) shown in (B), which document the presence of a large eccentric plaque (yellow arrows). *Lumen.

Future perspective

The clinical studies reviewed herein demonstrate the potential prognostic value of carotid MRI for subsequent TIA or stroke in asymptomatic and recently symptomatic individuals with moderate carotid stenosis. Furthermore, MRI may play a valuable role in examining mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of the high-risk carotid plaque. While the results from these initial studies are promising, the small number of events precluded multivariate analysis of the data, and highlights the need for larger, multicenter studies.

Additionally, initial findings suggest the need for imaging criteria in the form of a comprehensive plaque score that would provide greater positive predictive value for future events. In the study by Altaf et al. [87], IPH was equally prevalent in the contralateral (nonindex) carotid artery, yet there was only one TIA and no strokes referable to the nonindex side during follow-up. This suggests that factors other than the sole presence of IPH may also be important, such as FC status, size of the LRNC and IPH, the location of IPH (juxtaluminal or deep within the plaque) and degree of neovasculature. Larger studies are needed to test the hypothesis that specific baseline plaque features, independently or in combination, are associated with an increased risk for future ischemic events.

Validation of a comprehensive plaque score in prospective observational studies will provide the foundation for future randomized clinical trials. These trials will be needed to assess whether new plaque imaging-based selection criteria, by identifying individuals at higher risk than those identified by current stenosis-based criteria, will yield a greater absolute risk reduction that will be sufficient to justify carotid surgery or stenting in patients with moderate carotid stenosis.

Finally, the development of novel, molecular imaging techniques will advance the MRI field to the next critical level. The current clinically available MRI techniques described in this article provide important information regarding the structure and composition of human carotid atherosclerosis in vivo. Furthermore, dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI shows promise for providing an indirect measure of plaque neovasculature and the inflammatory activity of the plaque. The development of probes that package MRI contrast agents with targeted lipid-based nanoparticles [97-99] or HDLs [100] show great promise for providing a direct measure of plaque activity and function at a molecular level [101].

Conclusion

Carotid MRI has been extensively validated and provides quantitative information regarding the morphology and composition of human carotid atherosclerosis in vivo. Therefore, it provides an essential tool that will allow prospective studies to test the vulnerable plaque hypothesis.

Currently, there is a lack of consensus in the management of recently symptomatic patients with moderate carotid stenosis. Furthermore, improved methods of plaque imaging have documented that stenosis severity underestimates carotid plaque burden and plaque complexity, including those with angiographically normal appearing arteries. It is critical that we develop better plaque imaging-based methods for stroke risk stratification so that individuals with stable plaques will be spared from unnecessary surgery or stenting, and individuals with unstable, high-risk lesions who would be appropriately referred.

Finally, a better understanding of the characteristics of the vulnerable plaque will provide a foundation for further research on the pathogenesis of high-risk lesions, and perhaps lead to development of novel pharmacological therapy.

Executive summary

Amongst asymptomatic and symptomatic individuals with moderate carotid stenosis, specific MRI-identified carotid plaque features (e.g., intraplaque hemorrhage) are associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent transient ischemic attack or stroke. However, larger studies are needed to confirm these promising initial findings.

Measurement of stenosis underestimates carotid plaque burden. Furthermore, MRI studies have shown that complex plaque features, such as the lipid-rich necrotic core, intraplaque hemorrhage and fibrous cap rupture, are prevalent in carotid arteries with minimal stenosis – including those with angiographically normal appearing arteries.

Improved criteria for individual risk stratification will reduce overall healthcare costs by avoiding interventions that unnecessarily put individuals with stable plaques at risk for procedure-related complications, and appropriately select individuals with unstable, high-risk lesions for surgery or stenting.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge and are extremely grateful to their collaborators and colleagues, whose guidance, support and effort has been invaluable: N Balu, B Chu, M Ferguson, WS Kerwin, HR Underhill, D Xu, V Yarnykh, SC Cramer, G Garden, GP Jarvik, K O’Brien, NL Polissar, R Ross, S Schwartz, R Virmani, J Cai, G Canton, L Dong, A Kampschulte, F Li, M Oikawa, H Ota, T Saam, N Takaya, W Yu, X Zhao, H Chen, F Liu, J Wang, W Hamar, D Hippe, C Isaac, D Jensen, Z Miller, R Small, R Smith and T Zhu.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have received grant funding in the past from the NIH (R01 HL073401, P01 HL072262, R01 HL61851 and R01 HL56874), which has supported some of the work reviewed in this manuscript. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

-

▪

of interest

-

▪▪

of considerable interest

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119(3):e21–e181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown Dl, Boden-Albala B, Langa KM, et al. Projected costs of ischemic stroke in the United States. Neurology. 2006;67(8):1390–1395. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000237024.16438.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NASCET. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(7):445–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ECST. MRC European carotid surgery trial: interim results for symptomatic patients with severe (70–99%) or with mild (0–29%) carotid stenosis. Lancet. 1991;337(8752):1235–1243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayberg MR, Wilson SE, Yatsu F, et al. Carotid endarterectomy and prevention of cerebral ischemia in symptomatic carotid stenosis. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program 309 Trialist Group. JAMA. 1991;266(23):3289–3294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eliasziw M, Streifler JY, Fox AJ, Hachinski VC, Ferguson GG, Barnett HJ. Significance of plaque ulceration in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. Stroke. 1994;25(2):304–308. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothwell PM, Gutnikov SA, Warlow CP. Reanalysis of the final results of the European Carotid Surgery Trial. Stroke. 2003;34(2):514–523. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000054671.71777.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnett HJ, Taylor DW, Eliasziw M, et al. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(20):1415–1425. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811123392002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wasserman BA, Wityk RJ, Trout HH, 3rd, Virmani R. Low-grade carotid stenosis: looking beyond the lumen with MRI. Stroke. 2005;36(11):2504–2513. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185726.83152.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babiarz LS, Astor B, Mohamed MA, Wasserman BA. Comparison of gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance angiography with high-resolution black blood cardiovascular magnetic resonance for assessing carotid artery stenosis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2007;9(1):63–70. doi: 10.1080/10976640600843462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida K, Endo H, Sadamasa N, et al. Evaluation of carotid artery atherosclerotic plaque distribution by using long-axis high-resolution black-blood magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(6):1042–1048. doi: 10.3171/JNS.2008.109.12.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glagov S, Weisenberg E, Zarins CK, Stankunavicius R, Kolettis GJ. Compensatory enlargement of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(22):1371–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198705283162204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carr S, Farb A, Pearce WH, Virmani R, Yao JST. Atherosclerotic plaque rupture in symptomatic carotid artery stenosis. J Vasc Surg. 1996;23:755–766. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(96)70237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carr SC, Farb A, Pearce WH, Virmani R, Yao JST. Activated inflammatory cells are associated with plaque rupture in carotid artery stenosis. Surgery. 1997;122(4):757–763. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90084-2. discussion 763–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bassiouny HS, Sakaguchi Y, Mikucki SA, et al. Juxtalumenal location of plaque necrosis and neoformation in symptomatic carotid stenosis. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26(4):585–594. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mccarthy MJ, Loftus IM, Thompson MM, et al. Angiogenesis and the atherosclerotic carotid plaque: an association between symptomatology and plaque morphology. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(2):261–268. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mofidi R, Crotty TB, Mccarthy P, Sheehan SJ, Mehigan D, Keaveny TV. Association between plaque instability, angiogenesis and symptomatic carotid occlusive disease. Br J Surg. 2001;88(7):945–950. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redgrave JN, Lovett JK, Gallagher PJ, Rothwell PM. Histological assessment of 526 symptomatic carotid plaques in relation to the nature and timing of ischemic symptoms: the Oxford Plaque Study. Circulation. 2006;113(19):2320–2328. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.589044.. ▪▪ Largest series published to date describing the histological features of carotid plaques that are associated with recent transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke.

- 19.Spagnoli LG, Mauriello A, Sangiorgi G, et al. Extracranial thrombotically active carotid plaque as a risk factor for ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2004;292(15):1845–1852. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.15.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson JM, Kennelly MM, Decesare D, Morgan S, Sparrow A. Natural history of asymptomatic carotid plaque. Arch Surg. 1985;120(9):1010–1012. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390330022004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Holleran LW, Kennelly MM, McClurken M, Johnson JM. Natural history of asymptomatic carotid plaque. Five year follow-up study. Am J Surg. 1987;154(6):659–662. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(87)90238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sterpetti AV, Hunter WJ, Schultz RD. Importance of ulceration of carotid plaque in determining symptoms of cerebral ischemia. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;32(2):154–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sterpetti AV, Schultz RD, Feldhaus RJ, et al. Ultrasonographic features of carotid plaque and the risk of subsequent neurologic deficits. Surgery. 1988;104(4):652–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langsfeld M, Gray WAC, Lusby RJ. The role of plaque morphology and diameter reduction in the development of new symptoms in asymptomatic carotid arteries. J Vasc Surg. 1989;9(4):548–557. doi: 10.1067/mva.1989.vs0090548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belcaro G, Laurora G, Cesarone MR, et al. Ultrasonic classification of carotid plaques causing less than 60% stenosis according to ultrasound morphology and events. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;34(4):287–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bock RW, Gray-Weale AC, Mock PA, et al. The natural history of asymptomatic carotid artery disease. J Vasc Surg. 1993;17(1):160–169. doi: 10.1067/mva.1993.43142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manolio TA, Burke GL, O’Leary DH, et al. Relationships of cerebral MRI findings to ultrasonographic carotid atherosclerosis in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. CHS Collaborative Research Group. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(2):356–365. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Insana MF, Hall TJ, Fishback JL. Identifying acoustic scattering sources in normal renal parenchyma from the anisotropy in acoustic properties. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1991;17(6):613–626. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(91)90032-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin JM, Carson PL, Meyer CR. Anisotropic ultrasonic backscatter from the renal cortex. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1988;14(6):507–511. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(88)90112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hatsukami TS, Thackray BD, Primozich JF, et al. Echolucent regions in carotid plaque: preliminary analysis comparing three-dimensional histologic reconstructions to sonographic findings. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1994;20(8):743–749. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Widder B, Paulat K, Hackspacher J, et al. Morphological characterization of carotid artery stenoses by ultrasound duplex scanning. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1990;16(4):349–354. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(90)90064-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feeley TM, Leen EJ, Colgan MP, Moore DJ, Hourihane DO, Shanik GD. Histologic characteristics of carotid artery plaque. J Vasc Surg. 1991;13(5):719–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Leary DH, Holen J, Ricotta JJ, Roe S, Schenk EA. Carotid bifurcation disease: prediction of ulceration with B-mode US. Radiology. 1987;162(2):523–525. doi: 10.1148/radiology.162.2.3541034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Leary DH, Bryan FA, Goodison MW, et al. Measurement variability of carotid atherosclerosis: real-time (B-mode) ultrasonography and angiography. Stroke. 1987;18(6):1011–1017. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.6.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serfaty JM, Nonent M, Nighoghossian N, et al. Plaque density on CT, a potential marker of ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2006;66(1):118–120. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000191391.71614.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nandalur KR, Baskurt E, Hagspiel KD, et al. Carotid artery calcification on CT may independently predict stroke risk. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(2):547–552. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miralles M, Merino J, Busto M, Perich X, Barranco C, Vidal-Barraquer F. Quantification and characterization of carotid calcium with multi-detector CT-angiography. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;32(5):561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaalan WE, Cheng H, Gewertz B, et al. Degree of carotid plaque calcification in relation to symptomatic outcome and plaque inflammation. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40(2):262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Weert TT, Ouhlous M, Meijering E, et al. In vivo characterization and quantification of atherosclerotic carotid plaque components with multidetector computed tomography and histopathological correlation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(10):2366–2372. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000240518.90124.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tawakol A, Migrino RQ, Bashian GG, et al. In vivo18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging provides a noninvasive measure of carotid plaque inflammation in patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(9):1818–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davies JR, Rudd JH, Fryer TD, et al. Identification of culprit lesions after transient ischemic attack by combined 18F fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography and high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke. 2005;36(12):2642–2647. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000190896.67743.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudd JH, Myers KS, Bansilal S, et al. 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging of atherosclerotic plaque inflammation is highly reproducible: implications for atherosclerosis therapy trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(9):892–896. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calcagno C, Cornily JC, Hyafil F, et al. Correlation between plaque neovascularization, 18F-FDG-PET uptake and dynamic contrast enhanced MRI perfusion parameters in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis. Presented at: International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; Berlin, Germany. 19–25 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hatsukami TS, Ross R, Polissar NL, Yuan C. Visualization of fibrous cap thickness and rupture in human atherosclerotic carotid plaque in vivo with high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2000;102(9):959–964. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.9.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitsumori LM, Hatsukami TS, Ferguson MS, Kerwin WS, Cai J, Yuan C. In vivo accuracy of multisequence MRI for identifying unstable fibrous caps in advanced human carotid plaques. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;17(4):410–420. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trivedi RA, U-King-Im J, Graves MJ, et al. Multi-sequence in vivo MRI can quantify fibrous cap and lipid core components in human carotid atherosclerotic plaques. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;28(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trivedi RA, U-King-Im J, Graves MJ, et al. MRI-derived measurements of fibrous-cap and lipid-core thickness: the potential for identifying vulnerable carotid plaques in vivo. Neuroradiology. 2004;46(9):738–743. doi: 10.1007/s00234-004-1247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cai J, Hatsukami TS, Ferguson MS, et al. In vivo quantitative measurement of intact fibrous cap and lipid-rich necrotic core size in atherosclerotic carotid plaque: comparison of high-resolution, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and histology. Circulation. 2005;112(22):3437–3444. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.528174.. ▪ Demonstrates the added value of gadolinium contrast for MRI plaque characterization.

- 49.Shinnar M, Fallon JT, Wehrli S, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of ex vivo MRI for human atherosclerotic plaque characterization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(11):2756–2761. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.11.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wasserman BA, Smith WI, Trout HH, 3, Cannon RO, 3, Balaban RS, Arai AE. Carotid artery atherosclerosis: in vivo morphologic characterization with gadolinium-enhanced double-oblique MRI initial results. Radiology. 2002;223(2):566–573. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2232010659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moody AR, Murphy RE, Morgan PS, et al. Characterization of complicated carotid plaque with magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging in patients with cerebral ischemia. Circulation. 2003;107(24):3047–3052. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000074222.61572.44.. ▪ Histological validation of MRI identification of carotid plaque hemorrhage.

- 52.Toussaint JF, Lamuraglia GM, Southern JF, Fuster V, Kantor HL. Magnetic resonance images lipid, fibrous, calcified, hemorrhagic, and thrombotic components of human atherosclerosis in vivo. Circulation. 1996;94(5):932–938. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fayad ZA, Fuster V. Characterization of atherosclerotic plaques by magnetic resonance imaging. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;902:173–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saam T, Ferguson MS, Yarnykh VL, et al. Quantitative evaluation of carotid plaque composition by in vivo MRI. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(1):234–239. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000149867.61851.31.. ▪ Histological validation of MRI quantification of carotid plaque composition.

- 55.Kampschulte A, Ferguson MS, Kerwin WS, et al. Differentiation of intraplaque versus juxtaluminal hemorrhage/thrombus in advanced human carotid atherosclerotic lesions by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2004;110(20):3239–3244. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147287.23741.9A.. ▪ Histological validation of MRI quantification of carotid plaque composition.

- 56.Yuan C, Mitsumori LM, Ferguson MS, et al. In vivo accuracy of multispectral magnetic resonance imaging for identifying lipid-rich necrotic cores and intraplaque hemorrhage in advanced human carotid plaques. Circulation. 2001;104(17):2051–2056. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takaya N, Cai J, Ferguson MS, et al. Intra- and interreader reproducibility of magnetic resonance imaging for quantifying the lipid-rich necrotic core is improved with gadolinium contrast enhancement. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24(1):203–210. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oppenheim C, Naggara O, Touze E, et al. High-resolution MRI of the cervical arterial wall: what the radiologist needs to know. Radiographics. 2009;29(5):1413–1431. doi: 10.1148/rg.295085183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kerwin W, Hooker A, Spilker M, et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging analysis of neovasculature volume in carotid atherosclerotic plaque. Circulation. 2003;107(6):851–856. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048145.52309.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kerwin WS, O’Brien KD, Ferguson MS, Polissar N, Hatsukami TS, Yuan C. Inflammation in carotid atherosclerotic plaque: a dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI study. Radiology. 2006;241(2):459–468. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2412051336.. ▪ Histological validation of dynamic contrast enhanced MRI for quantifying neovasculature and macrophage content in carotid atherosclerosis.

- 61.Hayes CE, Mathis CM, Yuan C. Surface coil phased arrays for high resolution imaging of the carotid arteries. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1996;1:109–112. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880060121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fayad ZA, Fuster V. Clinical imaging of the high-risk or vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque. Circ Res. 2001;89(4):305–316. doi: 10.1161/hh1601.095596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chu B, Ferguson MS, Chen H, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance features of the disruption-prone and the disrupted carotid plaque. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(7):883–896. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yuan C, Kerwin WS, Yarnykh VL, et al. MRI of atherosclerosis in clinical trials. NMR Biomed. 2006;19(6):636–654. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saam T, Hatsukami TS, Takaya N, et al. The vulnerable, or high-risk, atherosclerotic plaque: noninvasive MRI for characterization and assessment. Radiology. 2007;244(1):64–77. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2441051769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yuan C, Kerwin WS. MRI of atherosclerosis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;19(6):710–719. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fayad ZA, Fuster V, Fallon JT, et al. Noninvasive in vivo human coronary artery lumen and wall imaging using black-blood magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2000;102(5):506–510. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.5.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chu B, Kampschulte A, Ferguson MS, et al. Hemorrhage in the atherosclerotic carotid plaque: a high-resolution MRI study. Stroke. 2004;35(5):1079–1084. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000125856.25309.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Winternitz MC, Thomas RM, Le Compte PM. The Biology of Arterioscleriosis. CC Thomas; Springfield, IL, USA: 1938. [Google Scholar]

- 70.O’Brien KD, McDonald TO, Chait A, Allen MD, Alpers CE. Neovascular expression of e-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in human atherosclerosis and their relation to intimal leukocyte content. Circulation. 1996;93:672–682. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.4.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Galis ZS, Muszynski M, Sukhova GK, et al. Cytokine-stimulated human vascular smooth muscle cells synthesize a complement of enzymes required for extracellular matrix digestion. Circ Res. 1994;75(1):181–189. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Galis ZS, Sukhova GK, Lark MW, Libby P. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases and matrix degrading activity in vulnerable regions of human atherosclerotic plaques. J Clin Invest. 1994;94(6):2493–2503. doi: 10.1172/JCI117619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nikkari ST, O’Brien KD, Ferguson M, et al. Interstitial collagenase (MMP-1) expression in human carotid atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1995;92(6):1393–1398. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.6.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Levy AP, Moreno PR. Intraplaque hemorrhage. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6(5):479–488. doi: 10.2174/156652406778018626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yuan C, Kerwin WS, Ferguson MS, et al. Contrast-enhanced high resolution MRI for atherosclerotic carotid artery tissue characterization. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;15(1):62–67. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moreno PR, Purushothaman KR, Sirol M, Levy AP, Fuster V. Neovascularization in human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2006;113(18):2245–2252. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.578955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.O’Brien KD, Allen MD, Mcdonald TO, et al. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 is expressed in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques. Implications for the mode of progression of advanced coronary atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(2):945–951. doi: 10.1172/JCI116670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.De Boer OJ, Van Der Wal AC, Teeling P, Becker AE. Leucocyte recruitment in rupture prone regions of lipid-rich plaques: a prominent role for neovascularization? Cardiovasc Res. 1999;41(2):443–449. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moulton KS, Vakili K, Zurakowski D, et al. Inhibition of plaque neovascularization reduces macrophage accumulation and progression of advanced atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(8):4736–4741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730843100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Celletti FL, Waugh JM, Amabile PG, Kao EY, Boroumand S, Dake MD. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated neointima progression with angiostatin or paclitaxel. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13(7):703–707. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61847-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Padhani AR. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in clinical oncology: current status and future directions. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16(4):407–422. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tofts PS, Brix G, Buckley DL, et al. Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: standardized quantities and symbols. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;10(3):223–232. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199909)10:3<223::aid-jmri2>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Barter PJ, Nicholls S, Rye KA, Anantharamaiah GM, Navab M, Fogelman AM. Anti-inflammatory properties of HDL. Circ Res. 2004;95(8):764–772. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146094.59640.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Botti TP, Amin H, Hiltscher L, Wissler RW. A comparison of the quantitation of macrophage foam cell populations and the extent of apolipoprotein E deposition in developing atherosclerotic lesions in young people: high and low serum thiocyanate groups as an indication of smoking. PDAY Research Group. Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth. Atherosclerosis. 1996;124(2):191–202. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(96)05825-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Takaya N, Yuan C, Chu B, et al. Association between carotid plaque characteristics and subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular events: a prospective assessment with MRI – initial results. Stroke. 2006;37(3):818–823. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000204638.91099.91.. ▪▪Prospective MRI study examining baseline plaque characteristics that are associated with a higher risk of future TIA or stroke.

- 86.Singh N, Moody AR, Gladstone DJ, et al. Moderate carotid artery stenosis: MRI-depicted intraplaque hemorrhage predicts risk of cerebrovascular ischemic events in asymptomatic men. Radiology. 2009;252(2):502–508. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2522080792.. ▪▪Prospective study examining the risk of TIA or stroke in initially asymptomatic individuals with moderate carotid stenosis with and without intraplaque hemorrhage.

- 87.Altaf N, Daniels L, Morgan PS, et al. Detection of intraplaque hemorrhage by magnetic resonance imaging in symptomatic patients with mild to moderate carotid stenosis predicts recurrent neurological events. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47(2):337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.064.. ▪▪Prospective study examining the risk of TIA or stroke in symptomatic individuals with mild-to-moderate carotid stenosis with and without intraplaque hemorrhage.

- 88.Kolodgie FD, Gold HK, Burke AP, et al. Intraplaque hemorrhage and progression of coronary atheroma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(24):2316–2325. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Takaya N, Yuan C, Chu B, et al. Presence of intraplaque hemorrhage stimulates progression of carotid atherosclerotic plaques: a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging study. Circulation. 2005;111(21):2768–2775. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.504167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Underhill HR, Yuan C, Yarnykh VL, et al. Arterial remodeling in the subclinical carotid artery: a natural history study. JACC. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.08.007. In Press.. ▪ Prospective study examining the clinical and carotid plaque features associated with plaque progression and remodeling patterns.

- 91.Yuan C, Zhang SX, Polissar NL, et al. Identification of fibrous cap rupture with magnetic resonance imaging is highly associated with recent transient ischemic attack or stroke. Circulation. 2002;105(2):181–185. doi: 10.1161/hc0202.102121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Underhill HR, Yuan C, Yarnykh VL, et al. Predictors of surface disruption with MRI in asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Am J Neuroradiol. 2009 doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1842. In Press.. ▪ Prospective study examining the clinical and carotid plaque features associated with subsequent plaque disruption.

- 93.Oikawa M, Kerwin W, Underhill H, Yuan C, Polissar N, Hatsukami T. Association between adventitial vaso vasorum and incident fibrous cap rupture: a prospective, longitudinal dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI study. Circulation. 2007;116(Suppl. II):410. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Saam T, Underhill HR, Chu B, et al. Prevalence of American Heart Association type VI carotid atherosclerotic lesions identified by magnetic resonance imaging for different levels of stenosis as measured by duplex ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(10):1014–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.054.. ▪▪ MRI study examining the prevalence of intraplaque hemorrhage, fibrous cap rupture, lipid-rich necrotic core across all stenoses.

- 95.Dong L, Hatsukami T, Ota H, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography measurement of carotid stenosis underestimates plaque burden identified by magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2008;118(18 Suppl. 2):S757–S758. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dong L, Underhill HR, Yu W, et al. Geometric and compositional appearance of atheroma in an angiographically normal carotid artery in patients with atherosclerosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009 doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1793. Epub ahead of print.. ▪ MRI study examining the prevalence of plaque and compostional features in angiographically normal appearing carotid arteries.

- 97.Briley-Saebo KC, Mulder WJ, Mani V, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques: current imaging strategies and molecular imaging probes. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26(3):460–479. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Briley-Saebo KC, Shaw PX, Mulder WJ, et al. Targeted molecular probes for imaging atherosclerotic lesions with magnetic resonance using antibodies that recognize oxidation-specific epitopes. Circulation. 2008;117(25):3206–3215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.757120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Amirbekian V, Lipinski MJ, Briley-Saebo KC, et al. Detecting and assessing macrophages in vivo to evaluate atherosclerosis noninvasively using molecular MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(3):961–966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606281104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chen W, Vucic E, Leupold E, et al. Incorporation of an apoE-derived lipopeptide in high-density lipoprotein MRI contrast agents for enhanced imaging of macrophages in atherosclerosis. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2008;3(6):233–242. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sanz J, Fayad ZA. Imaging of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2008;451(7181):953–957. doi: 10.1038/nature06803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]