Abstract

Type III/λ interferons (IFNs) were discovered less than a decade ago and are still in the process of being characterized. Although previous studies have focused on the function of IFN-λ3 (also known as interleukin (IL)-28B) in a small animal model, it is unknown whether these functions would translate to a larger, more relevant model. Thus in the present study, we have used DNA vaccination as a method of studying the influence of IFN-λ3 on adaptive immune responses in rhesus macaques. Results of our study show for the first time that IFN-λ3 has significant influence on antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell function, especially in regards to cytotoxicity. Peripheral CD8+ T cells from animals that were administered IFN-λ3 showed substantially increased cytotoxic responses as gauged by CD107a and granzyme B coexpression as well as perforin release. Moreover, CD8+ T cells isolated from the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) of animals receiving IFN-λ3 loaded significant amounts of granzyme B upon extended antigenic stimulation and induced significantly more granzyme B-mediated cell death of peptide pulsed targets. These data suggest that IFN-λ3 is a potent effector of the immune system with special emphasis on CD8+ T-cell killing functions which warrants further study as a possible immunoadjuvant.

Introduction

Interferons (IFNs) are cytokines that play important roles in both innate and adaptive responses to viral infections and are currently classified into three main types, known as type I, type II, or type III IFNs.1,2,3,4,5 Each type consists of unique members produced from varying cell types and each has its own unique receptor.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 The type III IFN family (also known as the λ-IFNs) has only recently been identified4 and is comprised of three members known as IFN-λ1, -λ2 and -λ3, or interleukin (IL)-29, IL-28A, and IL-28B, respectively.4

Initial study of type III IFNs suggest that IL-28B/IFN-λ3, in particular, may harbor the ability to induce potent innate antiviral responses in vitro9,10 via signaling through the IL-28 receptor complex, whose expression has been verified on a variety of cells, including lymphocytes.11 However, few studies have been performed in effort to elaborate how IL-28B/IFN-λ3 influences the adaptive immune response in vivo.12,13 In our own previous study, we performed an initial characterization of the ability of this IFN to influence adaptive cellular immunity in a small animal model. That study suggested that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 had the potential to induce helper T-cell type 1-biased adaptive cellular immune responses in vivo, as evidenced by increased antigen-specific IFN-γ release when compared with responses generated to antigen alone.12

Although there are limited studies of IL-28B/IFN-λ3 in mouse models, to date there are no studies of this IFN using a nonhuman primate model, a point which underscores the fact that our understanding of type III IFNs in relevant in vivo models is severely lacking. Additionally, while cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL)-related phenotyping of CD8+ T cells had been previously performed in a small animal model, no assay for effector activity nor analysis of CD4+ T-cell function had been reported.12 Thus, further characterization of this novel IFN and determination of its influence on adaptive immunity in relevant models is important. In order to address this, we have employed rhesus macaques in an human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) DNA immunization model consisting of three regimens; one using HIV antigen only, one consisting of antigen delivered in combination with IL-12 (a previously established, potent immune modulator12,14,15,16,17), and a third comprised of antigen in combination with IL-28B/IFN-λ3. The use of an immunization model allows not only for the characterization of IL-28B/IFN-λ3 in vivo in a nonhuman primate system, but also provides insight as to its possible utility as a vaccine adjuvant. Results of this study indicate that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 has comparatively little impact on CD4+ T-cell function, but is able to drive the generation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in macaques that exhibit considerable cytotoxicity as measured by CD107a and granzyme B coexpression as well as perforin release. When compared to IL-12, IL-28B/IFN-λ3 also increases long-lived responses in CD8+ T cells, suggesting that this IFN may drive the generation of memory more effectively than IL-12. Most importantly, IL-28B/IFN-λ3 endows CD8+ T cells from the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) of immunized animals with the ability to efficiently load granzyme B and imparts a significant ability to kill target cells displaying cognate peptide. These results show for the first time that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 exhibits an impressive influence on CD8+ T cells in a nonhuman primate model and is the first study to describe the ability of IL-28B/IFN-λ3 to significantly augment CTL effector functions.

Results

Study design and construct expression

We have previously shown that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 can skew adaptive immunity toward a helper T-cell type 1 bias in a small animal model.12 In the present study, we set out to determine what influences IL-28B/IFN-λ3 had in a nonhuman primate model as well as further the characterization of this IFN in reference to specific effector functions of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. In order to accomplish this, we employed an immunization model using multiclade consensus HIV Gag and Pol antigens in the presence or absence of IL-28B/IFN-λ3 or IL-12, which is another well-characterized immune modifier12,14,15,16,17 (Figure 1a). These cytokines were cloned into separate plasmids (Figure 1b) and expression of cytokine protein and it's secretion to the extracellular environment were verified by in vitro transfection of human embryonic kidney 293T cells (Figure 1c). Upon verification of adjuvant expression and secretion, groups of rhesus macaques (n = 4) were immunized with different immunization regimens using the schedule shown in Figure 1d.

Figure 1.

Group design, plasmid construction, and immunization schedule. (a) Rhesus macaques were divided into four groups of varying immunizations consisting of (b) HIV antigens with or without IL-12 or IL-28B/IFN-λ3 constructs. (c) IL-12 and IL-28B/IFN-λ3 expression and secretion were verified after in vitro transfection. (d) Animals were immunized and analysis was performed at indicated time points. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

IL-28B/IFN-λ3 increases type-1 cellular immune responses from PBMCs

In order to determine whether IL-28B/IFN-λ3 could drive antigen-specific helper T-cell type 1-biased responses, we employed a standard IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISpot) assay. We characterized responses over the course of the immunization period by assaying for IFN-γ 2 weeks after each immunization, analyzing the results on a per-animal basis (Figure 2a) as well as on a group-wide basis (Figure 2b). On a per-monkey basis within each group, all immunized animals responded strongly and exhibited robust ELISpot responses (Figure 2a). Analyzing responses averaged on a group-wide basis (Figure 2b) shows that after three immunizations the HIV Gag/Pol group exhibited 4,000 spot-forming units per million peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) whereas the IL-12 group averaged just over 4,500 spots. The IL-28B/IFN-λ3 group had a robust response with just over 5,000 spot-forming units per million PBMC which was the highest of any group. Taken together, these data show a trend in which the group that received IL-28B/IFN-λ3 showed the greatest T-cell benefit in antigen-specific IFN-γ production.

Figure 2.

Interferon-γ ELISpot responses. HIV-specific interferon-γ secretion induced by immunization with or without IL-12 or IL-28B/IFN-λ3 was measured via ELISpot over the course of the immunization period and analyzed on per (a) animal basis as well as on (b) a group-wide basis. ELISpot, enzyme-linked immunospot assay; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; SFU, spot-forming units.

As our previous small animal study has suggested possible modulation of the antibody response induced by these adjuvants during vaccination,12 we also assayed for p24-specific antibodies in the plasma of immunized animals (Supplementary Materials and Methods). No difference was seen in antibody titers (Supplementary Figure S1), suggesting that while both the IL-12 and IL-28B/IFN-λ3 adjuvants may influence cellular responses in immunized animals, antibody responses do not see this same benefit.

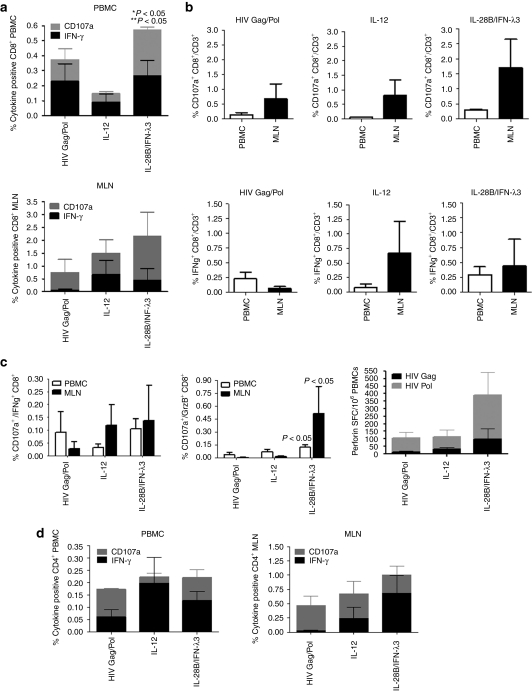

IL-28B/IFN-λ3 elicits robust long-lived CD8+ T-cell CD107a responses in peripheral blood and lymph nodes

A recent study has highlighted differences between IL-12 and IFN-α in regards to their ability to drive long-term memory in human CD8+ T cells18 and studies of IFN-α in the nonhuman primate system have revealed a number of similarities to human IFN-α.19 In the present study, we were interested in determining whether any difference existed between IL-12 and IL-28B/IFN-λ3 in regards to their ability to drive long-lasting responses. In order to asses this, we allowed 3 months to pass between the final immunization and our next subsequent immune analysis. By allowing this length of time to pass, we effectively permitted the primary response to the antigen expressed during the immunization period to wane, and thus responses seen at this later time point would reflect long-lived antigen-specific lymphocytes. After the 3-month rest period, we began our analysis by measuring antigen-specific IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells taken from peripheral blood. Results of this analysis show that antigen-specific IFN-γ production from the group that received IL-12 during immunization was 50% lower than any other group (Figure 3a). Additionally, CD107a expression in response to cognate antigens was higher in the IL-28B/IFN-λ3 group to a statistically significant degree when compared with either of the other two groups (Figure 3a), with an average response rate that was greater than threefold higher than the HIV Gag/Pol group and greater than fivefold higher than the group that received IL-12. In total, the group that received IL-12 had the poorest response rate of any group when analyzing CD8+ T cells exhibiting one or both of the functions tested, and response rates in animals receiving IL-28B/IFN-λ3 during immunization were higher than those receiving IL-12 to a statistically significant degree (Figure 3a). These results suggest that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 induces robust and long-lived immune responses from CD8+ T cells in the periphery, especially in regards to cytolytic potential.

Figure 3.

Analysis of T-cell function in the periphery (PBMC) and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) 3 months after immunization. (a) Interferon γ and CD107a responses were measured from peripheral (PBMC—top) and mesenteric (MLN—bottom) CD8+ T cells 3 months after vaccination. *P < 0.05 for CD107a responses between IL-28B/IFN-λ3 group and any other group. **P < 0.05 for summed responses between IL-28B/IFN-λ3 and IL-12. (b) Analysis of CD8+ T-cell responses are shown by group in the periphery (PBMC) and MLN. (c) Long-lived CD8+ T cells were analyzed for multiple functions including coexpression of CD107a and interferon γ (PBMC and MLN), CD107a and granzyme B (PBMC and MLN) or perforin release (PBMC). The P value shown is for comparison of CD107a/GrzB+ CD8+ T cells in the IL-28B/IFN-λ3 group compared with each of the other vaccination groups when looking in the PBMC subset. (d) Long-lived CD4+ T-cell function was measured in both the periphery (PBMC) and lymph nodes (MLN). HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

We next turned our analysis of antigen-specific immune responses to cells obtained from the MLN of the immunized animals using the same assays applied to PBMCs. Analysis of cells obtained from this compartment may be of particular importance in determining the potential efficacy of an HIV vaccine, as the MLN drain the intestinal mucosa, which is where HIV infection is first established.20,21 A detailed breakdown of the data reveals a trend between groups that was similar to what was seen in the periphery, as CD107a responses from CD8+ T cells taken from the MLN were twofold higher in the group that received IL-28B/IFN-λ3 as compared with antigen alone or antigen in combination with IL-12 (Figure 3a,b). Analysis of IFN-γ production in CD8+ T cells isolated from the MLN show that both IL-12 and IL-28B/IFN-λ3 afforded an impressive benefit to responding cells as compared to immunization with antigen alone (Figure 3a,b). When analyzing CD8+ T cells exhibiting one or both of these functions, the animals that received IL-28B/IFN-λ3 had the highest total responses, followed by IL-12 and antigen alone (Figure 4a). Taken together these data suggest that, as in the periphery, IL-28B/IFN-λ3 had the most significant impact on long-lived antigen-specific immune responses in CD8+ T cells in the MLN, and was more specifically able to generate a greater induction of cytolytic degranulation.

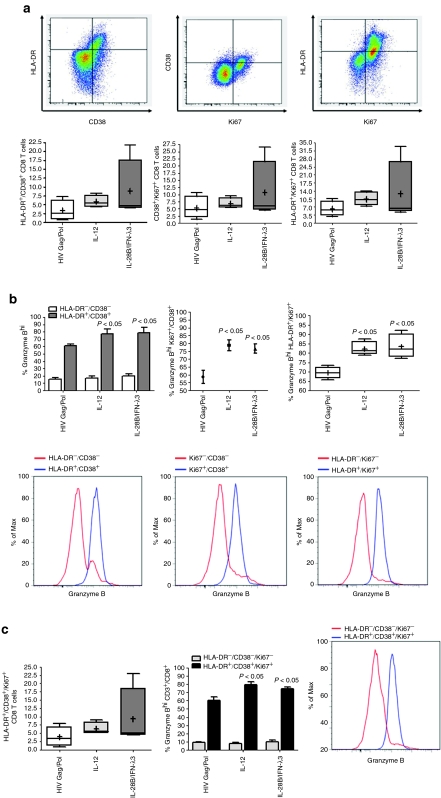

Figure 4.

Lytic granule loading assay of CD8+ T cells from mesenteric lymph nodes. Cells isolated from MLN of animals 3 months postimmunization were incubated with HIV Gag and Pol peptides for 6 days, at the end of which time cells were stained for activation markers CD38, HLA-DR, and Ki67. Representative staining is shown in a. (b) After the 6 day stimulation, CD8+ T cells from MLN exhibiting activation as determined from two-marker positivity were assayed for granzyme B content. (c) A more restrictive triple-positive activation requirement was applied to the stimulated CD8+ MLN T cells, and granzyme B content was again determined. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HLA, human leucocyte antigen; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; MLN, mesenteric lymph nodes; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

IL-28B/IFN-λ3 but not IL-12 creates robust 2-function responses and increases perforin release from long-lived antigen-specific PBMCs

Upon determining that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 was inducing long-lived monofunctional responses (Figure 3a,b), we turned our attention toward assaying for the presence of CD8+ T cells that were able to exhibit more than one function. By employing a Boolean gating method, we were able to compare the relative abilities of the different cytokines to induce the generation of CD8+ T cells that were positive for both IFN-γ production and CD107a expression in peripheral blood as well as the MLN. Results of this analysis show no significant functional difference in CD8+ T cells isolated from peripheral blood, but increased responses in CD8+ T cells taken from the MLN of animals in both the IL-12 and IL-28B/IFN-λ3 groups (Figure 3c). We next analyzed CD8+ T cells by assaying for CD107a expression in conjunction with examining intracellular granzyme B content. Cells that fall into this category have theoretically degranulated and been able to resynthesize a considerable amount of granzyme B within the 5 hours stimulation period of the assay. Only IL-28B/IFN-λ3 was able to induce CD8+ T cells that degranulated (CD107a+) but were able to rapidly resynthesize granzyme B (granzyme Bhi) to a statistically significant extent in peripheral blood (Figure 3c, white bars in the middle panel). Additionally, animals receiving IL-28B/IFN-λ3 exhibited an impressive and statistically significant increase in CD107a+/granzyme Bhi CD8+ T cells in the MLN as compared with any other group (Figure 3c, black bars in the middle panel). As CD107a expression is a measure of a cell's potential for cytolytic degranulation, but not an actual measure of lytic granule release, we further subjected PBMCs from each vaccinated group to a perforin ELISpot assay. By employing this assay, we were able to determine actual lytic granule release from cells taken from immunized animals, as well as analyzing group-wise differences in perforin, which we had not yet examined. Results from this assay show striking differences in the influence of the cytokines, with the IL-28B/IFN-λ3 group showing a fourfold increase in antigen-specific perforin release as compared to any other group (Figure 3c, right panel). These results suggest that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 induces strong, long-lived antigen-specific cytotoxic responses in CD8+ T cells, as exemplified by the presence of CD107a+/granzyme Bhi cells from both lymph nodes and peripheral blood as well as a fourfold increase in cytolytic granule release from PBMCs as determined by perforin ELISpot.

IL-12 and IL-28B/IFN-λ3 induce different response patterns in long-lived CD4+ T cells from the periphery and lymph nodes

Since our analysis suggested that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 was having a robust impact on CD8+ T-cell function both from the peripheral blood and from MLN 3 months after immunization, we decided to additionally analyze CD4+ T-cell function. CD4+ T cells harvested from peripheral blood and MLN were therefore assayed for IFN-γ production and CD107a expression in response to cognate peptides. Analysis of this data showed little impact of either cytokine on total CD4+ T-cell responses in peripheral blood, although responses in the IL-12 group were more skewed toward IFN-γ production than either of the other groups (Figure 3d, left panel). Responses seen in the MLN, however, showed a different pattern than what was seen in peripheral blood as IFN-γ production was higher in both groups receiving cytokine than in the group that received antigen alone (Figure 3d, right panel). Neither cytokine had a significant impact on CD107a expression in CD4+ T cells. A collective analysis of these data suggest a profile where neither cytokine had a significant impact on total responding CD4+ T cells in the periphery, but both were able to increase responses in the MLN, primarily by increasing IFN-γ production from these cells.

IL-28B/IFN-λ3 and IL-12 induce significant granzyme B loading of CD8+ T cells from MLN

Our analysis to this point had focused on short-term, rapid responses to peptide but had not yet examined CTL-related parameters in response to more prolonged antigen exposure. In order to address this, we cultured cells isolated from the MLN of immunized animals in vitro for 6 days in the presence or absence of cognate antigens. At the end of the 6-day incubation period, cells were stained for flow cytometric analysis to asses their relative abilities to load granzyme B. In order to identify our antigen-specific cells, we stained with a series of activation markers (CD38, human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR, and Ki6722,23,24) at the end of the stimulation period.24 Results of CD8+ T-cell staining for CD38, HLA-DR, or Ki67 are shown in Figure 4a. Regardless of which two-marker combination was used, trends of the average number of activated CD8+ T cells were similar: the group receiving the HIV Gag/Pol antigens alone during immunization showed the lowest activation, followed by the group that received IL-12. The group receiving IL-28B/IFN-λ3 consistently showed the highest percentage of activated CD8+ T cells at the end of the stimulation period (Figure 4a). We further analyzed these different subsets of activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells to asses how efficiently they had loaded granzyme B. At the end of the 6-day stimulation period, regardless of which two-marker system was used for analysis, both adjuvants were found to increase the granzyme B content of activated CD8+ T cells from the MLN (Figure 4b). Upon seeing significant granzyme B loading in CD8+ T cells from animals receiving cytokine using two-marker combinations, we decided to determine whether this trend persisted in a more restrictive setting in which CD8+ T cells subsets were required to express all three markers (CD38+/HLA-DR+/Ki67+) (Figure 4c). The trends of granzyme B loading were similar to the two-marker staining, as CD8+ T cells from the group receiving antigen alone exhibited a statistically lower percentage of cells staining granzyme Bhi when compared with the IL-12 and IL-28B/IFN-λ3 groups. Analysis of these data suggest that both IL-12 and IL-28B/IFN-λ3 have the ability to drive significantly increased granzyme B loading of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells upon extended antigenic stimulation.

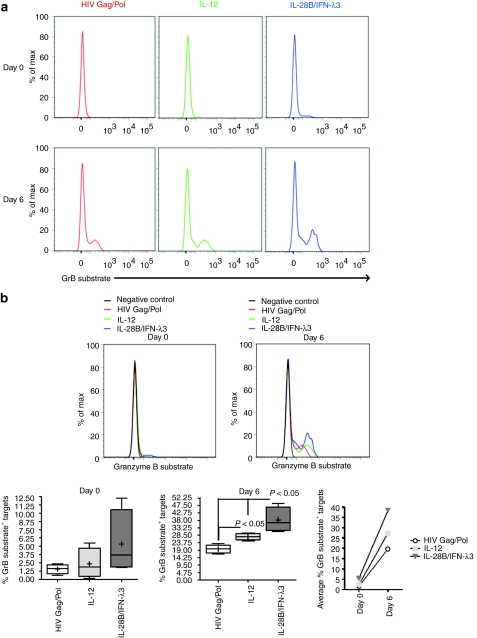

IL-28B/IFN-λ3 imparts significant cytotoxicity to CD8+ T cells from MLN after immunization

Although our analysis to this point had included phenotypic markers of CTLs (CD107a) or loading of cytolytic granules (granzyme B), we had not yet compared the relative abilities of IL-12 or IL-28B/IFN-λ3 to influence cell killing in a functional assay. In order to accomplish this, we employed a flow cytometric-based assay that measures the amount of active granzyme B delivered to target cells. Targets were pulsed with HIV antigens and coincubated with effectors (cells harvested from MLN) that had been stimulated with HIV Gag and Pol peptides for 6 days (day 6) or rested overnight without antigen stimulation (day 0). In order to normalize the number of effectors used, the activation markers described above (CD38/HLA-DR/Ki67) were employed to determine the number of antigen-specific cells to be added to the targets to achieve a 15:1 effector-to-target ratio. Analysis of granzyme B activity in targets incubated with day 0 effectors or day 6 effectors yielded different results based on immunization regimen or before stimulation with HIV antigen (Figure 5a). Day 0 effectors from animals receiving HIV Gag/Pol or receiving IL-12 mediated little cytotoxicity (1.59 and 2.3%), whereas the cytotoxic activity from animals receiving IL-28B/IFN-λ3 during immunization was two- to threefold higher at 5.3% (Figure 5b). Incubating effectors with cognate antigen for 6 days before exposure to targets lead to impressive increases in cytotoxic activity over day 0 cells (Figure 5b). Day 6 effectors from animals receiving antigen only delivered active granzyme B to an average of 19.8% of the targets (Figure 5b). Animals receiving cytokines in addition to antigen showed more impressive cytotoxic activity, with effectors from animals that were administered IL-12 delivering active granzyme B to 27.5% of targets, which was a statistically significant increase over effectors from animals receiving HIV Gag/Pol. Day 6 effectors from animals that received IL-28B/IFN-λ3 during immunization showed the highest cytotoxic activity, delivering active granzyme B to roughly two times as many targets as the group receiving antigens only (19.8 versus 38.3%) and was a statistically significant increase over both the HIV Gag/Pol and the IL-12 immunization groups. Collectively these data suggest that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 clearly exhibits a robust and significant increase in cell killing after antigenic stimulation when compared with antigen alone or even with the addition of the robust IL-12 adjuvant. These data suggest that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 is a potent driver of CTL-mediated killing activity that may, in some cases, rival those induced by IL-12.

Figure 5.

Activated granzyme B delivery from antigen-specific CTLs to targets. CD8+ T cells (CTLs) from MLN left unstimulated (day 0) or stimulated for 6 days (day 6) with HIV Gag and Pol in the same fashion as the lytic granule loading assay were incubated with autologous targets for 1 hour. The presence of active granzyme B was determined by assaying for fluorescent granzyme B substrate in target cells. Representative staining is shown in a. (b) Overlays of CTL-based killing via delivery of active granzyme B from day 0 and day 6 cells, as well graphical representations of killing on day 0, day 6, or the average increase in killing from day 0 to day 6. CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocytes; GrB, granzyme B; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HLA, human leucocyte antigen; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; MLN, mesenteric lymph nodes;PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Discussion

The λ IFNs represent a novel class of cytokine whose use in nonhuman primate vaccination settings has not been previously studied. Our previous study of IL-28B/IFN-λ3 in a small animal model allowed for analysis of its impact on adaptive immune responses, and results of that study suggested that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 could drive the production of CD8+ T cells that exhibited activities associated with improved CTL activity.12 Although these types of influences induced by cytokine adjuvants in small animal models often do not translate to nonhuman primate models,25 we show here that this is not the case for IL-28B/IFN-λ3. Results of the present study using IL-28B/IFN-λ3 as an adjuvant in HIV DNA vaccination in rhesus macaques show that it is a potent inducer of CD8+ T cells in both peripheral blood as well as MLN that exhibit significant CTL activity as determined by CD107a expression, perforin ELISpot, granzyme B loading and, most importantly, delivery of active granzyme B to target cells displaying cognate peptide. Taken together, these data suggest that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 is a strong candidate for further testing in vaccine studies.

This is the first study of IL-28B/IFN-λ3 in nonhuman primates and the first to suggest that, when used as an adjuvant in a DNA vaccine in rhesus macaques, this IFN is able to drive robust IFN-γ responses as well as statistically significant levels of antigen-specific CTL-based cell killing. In this regard, differences in cell killing induced by the IL-12 or IL-28B/IFN-λ3 adjuvants are intriguing, especially when one considers that both adjuvants were able to induce better loading of granzyme B in CD8+ T cells as compared with vaccination using antigen alone. The difference, then, may be connected to the differential expression of CD107a between the vaccination groups. When analysis of CD8+ T-cell function is performed using both CD107a responses as well as granzyme B loading, the pattern of cell killing from each group becomes clearer. When analyzing cells isolated from the MLN, the data shows that the group that received antigen only showed the lowest CD107a expression in addition to the poorest loading of granzyme B of any group. These two factors resulted in the CTL activity from this group being lower than that of the groups that received IL-12 or IL-28B/IFN-λ3. IL-12 did not significantly augment HIV-specific CD107a expression when compared with the antigen only group, but it did allow for greater granzyme B loading of CD8+ T cells. Thus, CTLs from animals receiving the IL-12 adjuvant may have showed better cell-killing activity than the group receiving antigen alone due to the fact that they had more granzyme B to deliver to targets and thus were more efficient killers. The group that received IL-28B/IFN-λ3 as an adjuvant exhibited the most impressive induction of CD8+ T cells displaying CD107a in addition to a significantly increased ability to load granzyme B. This data would suggest that this group exhibited the greatest number of CD8+ T cells that were able to load granzyme B in addition to having the greatest number of cells degranulating (CD107a+) which resulted in this group showing the best cell killing of any group. The phenomenon of cytokines being able to upregulate lytic granules while failing to induce degranulation is not unheard of, as a similar pattern was observed using IL-12 and IL-28B/IFN-λ3 in small animal model and a previous study of CD8+ T cells isolated from HIV-infected patients showed that treatment with IL-15 upregulated both perforin and CD107a, whereas treatment with IL-21 upregulated only perforin, without increasing degranulation capacity.26 A similar phenomenon seems to be at work in our present work, although the specific mechanisms for this difference require further study.

The data presented here also show that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 induced more robust long-lived CD8+ T cells, whereas IL-12 seemed to drive the generation of effector T cells that were not observed at more distant time points, such as 3 months after vaccination. This difference may be related to a recent study that highlighted the ability of IL-12 to drive a short-lived effector CD8+ T-cell phenotype, whereas the type I IFN drove these cells toward a differentiation pathway that suggested a long-lived memory phenotype,18 although additional study is required to verify this possibility. This may also suggest that inclusion of IL-28B/IFN-λ3 is of great importance during the first and possibly second immunization, as its activity may be expanding the pool of antigen-specific cells that are programmed to convert to a long-lived memory phenotype. Also of considerable interest is the fact that although our previous study using a small animal model showed that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 was able to exert some influence on CD4+ T-cell responses,12 this influence was not observed in the present study. The reasons behind this difference are currently unclear, but may be related to differential expression of the IL-28 receptor complex on macaque CD4+ T cells as compared with mouse CD4+ T cells. Indeed, comparative lymphocyte phenotyping for the IL-28 receptor complex has not yet been extensively performed in macaques, and may be of significant value for studies of immunological function in the nonhuman primate model.

The type of influence exerted by IL-28B/IFN-λ3 may make it an attractive vaccine adjuvant when viewed in the context of viral infections. This may be specifically true in the case of HIV infection, as a recent report on the CTL activities of HIV-infected long-term nonprogressors and progressors has shown that robust granzyme-B-mediated killing of target cells is seen in long-term nonprogressors but not in patients that have progressed to AIDS.27 Additionally, the data presented here suggest that IL-28B/IFN-λ3 is attractive for continued study in vivo where CTL activity may be of great importance in treatments of other pathologies such as other chronic infections or cancer.

Materials and Methods

Animals. Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were housed at BIOQUAL (Rockville, MD), in accordance with the standards of the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Animals were allowed to acclimate for at least 30 days in quarantine prior to any experimentation.

Plasmids. Both the HIV Gag (pGag4Y) and HIV Pol (pMPol) antigen constructs were expressed using a pVAX1 plasmid backbone (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Both Gag and Pol were constructed as consensus sequences of the respective genes from HIV-1 inclusive of clades A–D with several modifications including: the addition of a kozak sequence, a substituted immunoglobulin secretory leader sequence, and codon as well as RNA optimization for expression in Homo sapiens.17,28,29,30,31 Additionally, small deletions were made in seven different locations within the Pol construct in order to inactivate HIV protease, reverse transcriptase, RNAse H and integrase for safety measures.

The IL-28B adjuvant construct was created by back-translating the M. mulatta protein listed in the NCBI Protein Database (Locus XP_001086865) to DNA and inserting the resulting gene into a pVAX1 plasmid backbone (GeneArt, Renensberg, Germany). The IL-12 construct was constructed in the dual-promoter WLV104M backbone to allow the p35 and p40 subunits to be encoded into a single plasmid.12 Both constructs were optimized for expression in H. sapiens in addition to other optimization techniques including the addition of a kozak sequence and an added leader sequence. Plasmids were expanded and formulated at Inovio Pharmaceuticals (The Woodlands, TX), in sterile water for injection.

Immunization. Animals were divided to include four rhesus macaques per group. All immunized macaques received plasmid injections intramuscularly in the quadriceps muscle at weeks 0, 4, and 8 of 0.5 mg of each HIV Gag (pGag4Y) and HIV Pol (pMPol) with or without adjuvant followed by electroporation using the Cellectra electroporation device (Inovio Immune Therapeutics Division of VGX Pharmaceuticals). Groups were divided by the presence or absence of cytokine adjuvants. One group received 0.3 mg of optimized macaque IL-12, whereas others received 0.3 mg of optimized macaque IL-28B/IFN-λ3. All plasmids, regardless of the inclusion of adjuvant or not, were delivered to the same site.

PBMC and MLN isolation. Animals were bled every 2 weeks for the duration of the study, including 2 weeks before the initiation of immunization. Ten milliliter of blood were collected via venipuncture in tubes containing EDTA. PBMCs were isolated by standard Ficoll–Hypaque centrifugation and then resuspended in complete culture medium (RPMI 1640 with 2 mmol/l, l-glutamine supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 55 µmol/l β-mercaptoethanol). Red blood cells were lysed with ammonium chloride–potassium lysis buffer (Cambrex Bio Science, East Rutherford, NJ). Lymphocytes were isolated from MLN by crushing the nodes in a small volume of 1× phosphate-buffered saline and running the resulting cell suspension through a 0.5-µm filter. Cells were pelleted and ammonium chloride–potassium lysis buffer was added as above to remove any contaminating red blood cells. Resulting lymphocytes were resuspended in culture media in the same fashion as PBMCs.

ELISpot assay for IFN-γ and perforin. ELISpot were performed as previously described.32,33 Antigen-specific responses were determined by subtracting the number of spots in the negative control wells from the wells-containing peptides. Results are shown as the mean value (spots/million PBMC) obtained for triplicate wells.

Immunoglobulin G end-point titers were defined as the reciprocal serum dilution that resulted in optical density values that were greater than twice the average of optical density value of the bovine serum albumin wells.

Intracellular cytokine staining antibodies. The following antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA): CD3 (allophycocyanin-Cy7), IFN-γ (phycoerythrin-Cy7), CD8 (allophycocyanin), CD4 (PerCP-Cy5.5), CD107a (fluorescein isothiocyanate), CD14 (Pacific Blue), CD16 (Pacific Blue), CD19 (Pacific Blue), HLA-DR (Alexa Flour 700), Ki67 (fluorescein isothiocyanate). Granzyme B (phycoerythrin-Texas Red) was obtained from Invitrogen. CD38 (allophycocyanin) was obtained from the National Institutes of Health NonHuman Primate Reagent Resource.

Cell stimulation and intracellular cytokine staining. PBMCs were resuspended to 1 × 106 cells/100 µl in complete RPMI and plated in 96-well plates with stimulating peptides 100 µl at 1:200 dilutions in the presence of protein transport inhibitors, GolgiStop and GolgiPlug (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). An unstimulated (media alone) and positive control (Staphylococcus enterotoxin B, 1 µg/ml; Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was included in each assay. Cells were incubated for 5.5 hours at 37 °C. Following incubation, cells were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline and stained with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies to cell surface antigens. The cells were then washed and fixed using the Fixation and Permeabilization Kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Following fixation, cells were washed twice and stained with antibodies against intracellular targets. Following staining, the cells were again washed, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed on a flow cytometer.

Lytic granule loading assay and granzyme B cell-killing assay. The lytic granule loading assay was performed by plating 1 × 106 cells into a 96-well plate with the addition of HIV Gag and Pol Consensus Clade B and Pol 15-mer peptides (National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Program, Bethesda MD, catalogue numbers 8,117 and 6,208, respectively) or with dimethyl sulfoxide (control). Cells were incubated for 6 days, at the end of which time they were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and subjected to staining for CD3, CD4, CD8, CD38, HLA-DR, Ki67, and granzyme B using the same protocol as listed above.

The granzyme B cell-killing assay was performed using GranToxiLux PLUS (OncoImmunin, Gaithersburg, MD) per manufacturer's instructions. Day 0 or day 6 cells from the lytic granule loading assay were used as effectors to combine with autologous targets that had been pulsed with HIV Gag and Pol peptides for 1 hour at 37 °C. Effector-to-target ratio was normalized for all animals based on expression of CD38, HLA-DR, and Ki67 on effectors. Final effector-to-target ratios were 15:1.

Flow cytometry. Cells were analyzed on a modified LSR II flow cytometer (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo version 7.2.5 (TreeStar, San Carlos, CA). Data are reported after background correction.

Statistics. The statistical difference between immunization groups was assessed using a paired Student t-test or analysis of variance where appropriate and yielded a specific P value for each experimental group. Comparisons between samples with a P value <0.05 were considered statistically different and therefore significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. HIV-p24-specific plasma antibodies. Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported in part by funding from the NIH to D.B.W. and to M.P.M. from grant T32-AI070099 and by NIH/NIAID/DAIDS under an HVDDT contract award: HHSN272200800063C to Inovio Biomedical as well as HIVRAD grant P01-AI071739 to D.B.W. We thank Jake Yalley-Ogunro and Matt Collins at BIOQUAL for their help with animal handling and immunizations. The laboratory of D.B.W. has grant funding and collaborations or consulting including serving on scientific review committees for commercial entities and in the interest of disclosure therefore notes potential conflicts associated with this work with Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, VIRxSYS, Ichor, Inovio, Merck, Althea, Aldevron, and possibly others. The remaining authors declared no competing financial interests.

Supplementary Material

HIV-p24-specific plasma antibodies.

REFERENCES

- Ank N, West H., and, Paludan SR. IFN-λ: novel antiviral cytokines. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:373–379. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher SG, Sheikh F, Scarzello AJ, Romero-Weaver AL, Baker DP, Donnelly RP, et al. IFNα and IFNλ differ in their antiproliferative effects and duration of JAK/STAT signaling activity. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1109–1115. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.7.6192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A, Ohtsuki M, Hata M, Kobayashi E., and, Murakami T. Antitumor activity of IFN-λ in murine tumor models. J Immunol. 2006;176:7686–7694. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard P, Kindsvogel W, Xu W, Henderson K, Schlutsmeyer S, Whitmore TE, et al. IL-28, IL-29 and their class II cytokine receptor IL-28R. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:63–68. doi: 10.1038/ni873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzé G., and, Monneron D. IL-28 and IL-29: newcomers to the interferon family. Biochimie. 2007;89:729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach EA, Aguet M., and, Schreiber RD. The IFNγ receptor: a paradigm for cytokine receptor signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:563–591. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chill JH, Quadt SR, Levy R, Schreiber G., and, Anglister J. The human type I interferon receptor: NMR structure reveals the molecular basis of ligand binding. Structure. 2003;11:791–802. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzé G, Schreiber G, Piehler J., and, Pellegrini S. The receptor of the type I interferon family. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;316:71–95. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-71329-6_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ank N, West H, Bartholdy C, Eriksson K, Thomsen AR., and, Paludan SR. λ Interferon (IFN-λ), a type III IFN, is induced by viruses and IFNs and displays potent antiviral activity against select virus infections in vivo. J Virol. 2006;80:4501–4509. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4501-4509.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellgren, C, Gad H, Hamming OJ, Melchjorsen J., and, Hartmann R. Human interferon-λ3 is a potent member of the type III interferon family. Genes Immun. 2009;10:125–131. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebler J, Wirtz S, Weigmann B, Atreya I, Schmitt E, Kreft A, et al. IL-28A is a key regulator of T-cell-mediated liver injury via the T-box transcription factor T-bet. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:358–371. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow MP, Pankhong P, Laddy DJ, Schoenly KA, Yan J, Cisper N, et al. Comparative ability of IL-12 and IL-28B to regulate Treg populations and enhance adaptive cellular immunity. Blood. 2009;113:5868–5877. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numasaki, M, Tagawa M, Iwata F, Suzuki T, Nakamura A, Okada M, et al. IL-28 elicits antitumor responses against murine fibrosarcoma. J Immunol. 2007;178:5086–5098. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer JD, Robinson TM, Kutzler MA, Parkinson R, Calarota SA, Sidhu MK, et al. SIV DNA vaccine co-administered with IL-12 expression plasmid enhances CD8 SIV cellular immune responses in cynomolgus macaques. J Med Primatol. 2005;34:262–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2005.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong SY, Egan MA, Kutzler MA, Megati S, Masood A, Roopchard V, et al. Comparative ability of plasmid IL-12 and IL-15 to enhance cellular and humoral immune responses elicited by a SIVgag plasmid DNA vaccine and alter disease progression following SHIV(89.6P) challenge in rhesus macaques. Vaccine. 2007;25:4967–4982. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Maguire HC, Jr, Nottingham LK, Morrison LD, Tsai A, Sin JI, et al. Coadministration of IL-12 or IL-10 expression cassettes drives immune responses toward a Th1 phenotype. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1998;18:537–547. doi: 10.1089/jir.1998.18.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin JI, Kim JJ, Arnold RL, Shroff KE, McCallus D, Pachuk C, et al. IL-12 gene as a DNA vaccine adjuvant in a herpes mouse model: IL-12 enhances Th1-type CD4+ T cell-mediated protective immunity against herpes simplex virus-2 challenge. J Immunol. 1999;162:2912–2921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos HJ, Davis AM, Cole AG, Schatzle JD, Forman J., and, Farrar JD. Reciprocal responsiveness to interleukin-12 and interferon-α specifies human CD8+ effector versus central memory T-cell fates. Blood. 2009;113:5516–5525. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-188458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung E, Amrute SB, Abel K, Gupta G, Wang Y, Miller CJ, et al. Characterization of virus-responsive plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the rhesus macaque. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:426–435. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.3.426-435.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veazey RS, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV, Shvetz DE, Pauley DR, Knight HL, et al. Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science. 1998;280:427–431. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T, Jahn HU, Schmidt W, Riecken EO, Zeitz M., and, Ullrich R. Loss of CD4 T lymphocytes in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is more pronounced in the duodenal mucosa than in the peripheral blood. Berlin Diarrhea/Wasting Syndrome Study Group. Gut. 1995;37:524–529. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.4.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullwinkel, J, Baron-Luhr B, Lüdemann, A, Wohlenberg, C, Gerdes, J., and, Scholzen T. Ki-67 protein is associated with ribosomal RNA transcription in quiescent and proliferating cells. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:597–606. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatt NR, Villinger F, Bostik P, Gordon SN, Pereira L, Engram JC, et al. Availability of activated CD4+ T cells dictates the level of viremia in naturally SIV-infected sooty mangabeys. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2039–2049. doi: 10.1172/JCI33814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querec TD, Akondy RS, Lee EK, Cao W, Nakaya HI, Teuwen D, et al. Systems biology approach predicts immunogenicity of the yellow fever vaccine in humans. 2009. Nat Immunol. 10:116–125. doi: 10.1038/ni.1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow MP., and, Weiner DB. Cytokines as adjuvants for improving anti-HIV responses. AIDS. 2008;22:333–338. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f42461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L, Krishnan S, Strbo N, Liu H, Kolber MA, Lichtenheld MG, et al. Differential effects of IL-21 and IL-15 on perforin expression, lysosomal degranulation, and proliferation in CD8 T cells of patients with human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV) Blood. 2007;109:3873–3880. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-045278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migueles SA, Osborne CM, Royce C, Compton AA, Joshi RP, Weeks KA, et al. Lytic granule loading of CD8+ T cells is required for HIV-infected cell elimination associated with immune control. Immunity. 2008;29:1009–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schadeck EB, Sidhu M, Egan MA, Chong SY, Piacente P, Masood A, et al. A dose sparing effect by plasmid encoded IL-12 adjuvant on a SIVgag-plasmid DNA vaccine in rhesus macaques. Vaccine. 2006;24:4677–4687. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Hokey DA, Morrow MP, Corbitt N, Harris K, Harris D, et al. Novel SIVmac DNA vaccines encoding Env, Pol and Gag consensus proteins elicit strong cellular immune responses in cynomolgus macaques. Vaccine. 2009;27:3260–3266. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Reichenbach DK, Corbitt N, Hokey DA, Ramanathan MP, McKinney KA, et al. Induction of antitumor immunity in vivo following delivery of a novel HPV-16 DNA vaccine encoding an E6/E7 fusion antigen. Vaccine. 2009;27:431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JS, Kim JJ, Hwang D, Choo AY, Dang K, Maguire H, et al. Induction of potent Th1-type immune responses from a novel DNA vaccine for West Nile virus New York isolate (WNV-NY1999) J Infect Dis. 2001;184:809–816. doi: 10.1086/323395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao LA, Wu L, Khan AS, Hokey DA, Yan J, Dai A, et al. Combined effects of IL-12 and electroporation enhances the potency of DNA vaccination in macaques. Vaccine. 2008;26:3112–3120. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calarota SA, Hokey DA, Dai A, Jure-Kunkel MN, Balimane P., and, Weiner DB. Augmentation of SIV DNA vaccine-induced cellular immunity by targeting the 4-1BB costimulatory molecule. Vaccine. 2008;26:3121–3134. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

HIV-p24-specific plasma antibodies.