Abstract

Background

Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is a life-shortening genetic disease in which ~80% of deaths result from loss of lung function linked to inflammation due to chronic bacterial infection (principally Pseudomonas aeruginosa). Pulmonary exacerbations (intermittent episodes during which symptoms of lung infection increase and lung function decreases) can cause substantial resource utilization, morbidity, and irreversible loss of lung function. Intravenous antibiotic treatment to reduce exacerbation symptoms is standard management practice. However, no prospective studies have identified an optimal antibiotic treatment duration and this lack of objective data has been identified as an area of concern and interest.

Methods

We have retrospectively analyzed pulmonary function response data (as forced expiratory volume in one second; FEV1) from a previous blinded controlled CF exacerbation management study of intravenous ceftazidime/tobramycin and meropenem/tobramycin in which spirometry was conducted daily to assess the time course of pulmonary function response.

Results

Ninety-five patients in the study received antibiotics for at least 4 days and were included in our analyses. Patients received antibiotics for an average of 12.6 days (median = 13, SD = 3.2 days), with a range of 4 to 27 days. No significant differences were observed in mean or median treatment durations as functions of either treatment group or baseline lung disease stage. Average time from initiation of antibiotic treatment to highest observed FEV1 was 8.7 days (median = 10, SD = 4.0 days), with a range of zero to 19 days. Patients were treated an average of 3.9 days beyond the day of peak FEV1 (median = 3, SD = 3.8 days), with 89 patients (93.7%) experiencing their peak FEV1 improvement within 13 days. There were no differences in mean or median times to peak FEV1 as a function of treatment group, although the magnitude of FEV1 improvement differed between groups.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that antibiotic response to exacerbation as assessed by pulmonary function is essentially complete within 2 weeks of treatment initiation and relatively independent of the magnitude of pulmonary function response observed.

Introduction

Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is a life-shortening genetic disease in which ~80% of deaths result from loss of lung function linked to inflammation caused by chronic bacterial lung infection (principally Pseudomonas aeruginosa) [1,2]. Pulmonary exacerbations (intermittent episodes during which symptoms of lung infection increase and lung function decreases) can cause substantial resource utilization [3], morbidity [4], and irreversible loss of lung function [5].

A number of different signs, symptoms, and test results can contribute to the diagnosis of CF pulmonary exacerbation [2,4], with precipitous loss of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) most strongly associated with exacerbation diagnosis in patients old enough to reliably perform spirometry [6]. Because loss of lung function is the underlying cause of a majority of CF deaths [1], management of CF exacerbations includes an understandable emphasis on recovery of lung function [7]. Unfortunately, many patients fail to fully recover lost lung function despite this emphasis. One study has shown that 43% of patients treated for pulmonary exacerbation failed to completely reach their pre-exacerbation pulmonary function, and 24% failed to achieve even 95% of their pre-exacerbation function [5].

Administration of systemic antibiotics is an essential component of CF exacerbation management, particularly in patients chronically infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa [7,8]. Three blinded placebo-controlled clinical studies failed to demonstrate a significant antipseudomonal antibiotic effect on increased respiratory signs and symptoms associated with exacerbation [9-11] and only one of these studies could attribute a significant improvement in FEV1 % predicted to antibiotic treatment [11]. Regardless, treatment guidelines suggest that antibiotics be administered for a CF exacerbation "for a minimum of 10 days but often will be extended depending on the time course until clinical improvement is seen and the improvement or lack thereof, of pulmonary function tests" [7]. This guidance, which is based more on experience and consensus than evidence, does not address the question of when antibiotic regimens should be adjusted or abandoned entirely in the absence of complete recovery after extended treatment. A recent Cochrane review noted this problem and suggested that a randomized controlled trial comparing different antibiotic treatment durations could have important clinical and financial implications [12]. Similarly, a recent CF Foundation consensus document concluded that "there is insufficient evidence to recommend an optimal duration of antibiotic treatment of an acute exacerbation," noting that duration of therapy is "an important question that should be studied further" [8].

We have retrospectively analyzed data from a previous study of antibiotic treatment of CF exacerbation in which spirometry was conducted daily [13]. In this multicenter study, treatment duration was left to the individual investigator's discretion based upon their current standards of exacerbation management. Our purpose was to characterize FEV1 response to antibiotic therapy as a function of time to determine if FEV1 response continued or was attenuated with extended treatment.

Methods

Data were obtained from a previous blinded, randomized study comparing treatment with intravenous ceftazidime plus tobramycin (ceftaz/tobra) to treatment with meropenem plus tobramycin (mero/tobra) for acute pulmonary exacerbation [13]. This previous study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations found in the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. The study protocol and informed consent were approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Studies at each site. Informed consent was obtained from each subject. To be included in the current analyses, patients had to have been enrolled in the blinded, randomized portion of the previous study, have had spirometry performed at treatment initiation (Day 0) and have received four or more consecutive days of treatment with ceftaz/tobra or mero/tobra from initiation. Baseline lung disease stage ("early," FEV1 ≥ 70% predicted; "intermediate," FEV1 between 40% and 69% predicted; "advanced," FEV1 < 40% predicted), antibiotic treatment assignments, and all available daily spirometric measures beginning at Day 0 were collected for each patient. Relative change in FEV1 was calculated by subtracting a patient's Day 0 FEV1 value from the FEV1 value on any subsequent treatment day, and then dividing by the Day 0 value. Relative change values were expressed as percentages. Peak change in FEV1 was defined as the largest relative increase in FEV1 observed after initiation of treatment for each subject. Differences in median treatment durations and elapsed times from treatment initiation to observation of peak FEV1 were studied as functions of antibiotic treatment received and baseline lung disease stage by Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Differences in absolute and relative change in FEV1 from baseline between groups were analyzed by t tests.

Results

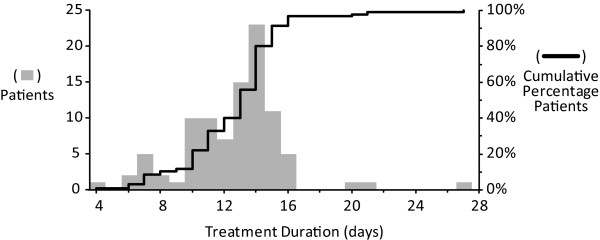

Ninety-five patients (50 treated with ceftaz/tobra and 45 treated with mero/tobra) met inclusion criteria and were included in this retrospective analysis. At initiation of treatment, 11 patients (11.6%) had an FEV1 of ≥70% predicted, 46 (48.4%) had an FEV1 of between 40% and 70% predicted, and 38 (40.0%) had an FEV1 of < 40% predicted. Baseline FEV1 values (in liters) for subgroups are provided in Table 1. Patients were treated with antibiotics for an average of 12.6 days (median = 13, SD = 3.2 days), with a range of 4 to 27 days (Table 1). Seventy-six patients (80%) had completed antibiotic treatment by 14 days, and 96.8% had completed treatment by 16 days (Figure 1). No significant differences were observed in mean or median antibiotic treatment durations as functions of either antibiotic treatment received or baseline lung disease stage, although there was a trend towards longer median treatment durations with mean greater impairment of baseline FEV1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Treatment Duration and Time to Peak FEV1 Measure

| Mean, days ± SD | Median, days | Range, days (min - max) | Interquartile Range, days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Antibiotic Treatment Duration |

||||

| All patients (n = 95) |

12.6 ± 3.2 |

13 |

23 (4 - 27) |

3 |

| ceftaz/tobra treated (n = 50) |

12.5 ± 2.8 |

12.5 |

12 (4 - 16) |

3.75 |

| mero/tobra treated (n = 45) |

12.8 ± 3.6 |

13 |

21 (6 - 27) |

3 |

| FEV1 ≥ 70% predicted (n = 11) |

11.9 ± 2.4 |

12 |

8 (7 - 15) |

3 |

| FEV1 40% - 69% predicted (n = 46) |

12.3 ± 2.8 |

13 |

15 (6 - 21) |

3 |

| FEV1 < 40% predicted (n = 38) |

13.2 ± 3.8 |

14 |

23 (4 - 27) |

3 |

|

Time to Peak FEV1 Measure |

||||

| All patients |

8.7 ± 4.0 |

10 |

19 (0 - 19) |

6.5 |

| ceftaz/tobra treated |

8.9 ± 4.0 |

10 |

15 (1 - 16) |

6.75 |

| mero/tobra treated |

8.5 ± 4.3 |

9 |

19 (0 - 19) |

5 |

| FEV1 ≥ 70% predicted |

7.9 ± 3.3 |

7 |

12 (4 - 15) |

5 |

| FEV1 40% - 69% predicted |

8.0 ± 4.2 |

9.5 |

15 (0 - 15) |

6 |

| FEV1 < 40% predicted | 9.9 ± 3.6 | 10 | 16 (3 - 19) | 4.75 |

Figure 1.

Distribution of antibiotic treatment durations. The gray bars show the distribution of antibiotic treatment duration in days for the 95 study patients (left vertical axis). The black line represents the cumulative percentage of patients having completed treatment by a given duration (right vertical axis).

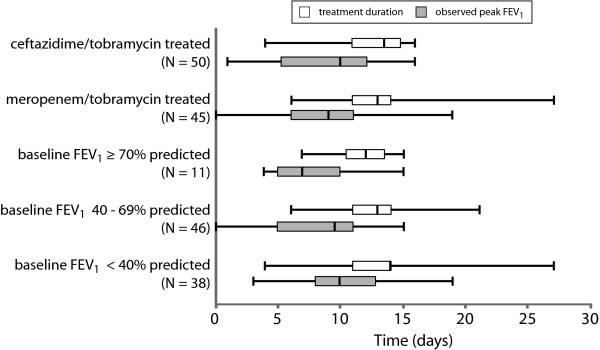

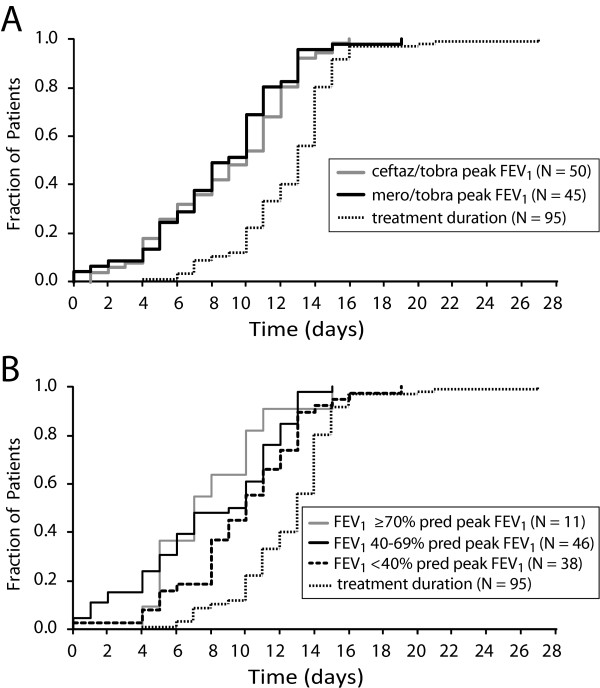

The average time from initiation of antibiotic treatment to the highest observed FEV1 for all patients was 8.7 days (median = 10, SD = 4.0 days), with a range of zero to 19 days (Table 1). Two patients (2.1%) did not experience an increase in FEV1 over their baseline values, despite being treated with antibiotics for 8 and 15 days. Twelve patients (12.6%) experienced their greatest relative improvement in FEV1 on their final day of antibiotic treatment, which occurred on average 11.5 days after initiation (median = 11, SD = 3.1 days). Patients were treated with antibiotics for an average of 3.9 days beyond the day that their peak FEV1 was observed (median = 3, SD = 3.8 days). The patient treated for the longest duration (27 days) was also the patient treated for the longest period after recording his or her peak FEV1 (at day 5). In all, 70 patients (73.7%) had already experienced their peak improvement in FEV1 by 11 days of antibiotic treatment, and 89 patients (93.7%) had experienced their peak improvement in FEV1 by 13 days of treatment. There was no significant difference observed in median time to peak FEV1 response observed between patients treated with ceftaz/tobra and those treated with mero/tobra (10 versus 9 days, P = 0.52)(Figures 2 and 3A). In contrast, mean time to peak FEV1 response was impacted by baseline lung disease stage, with patients entering the study with an FEV1 < 40% predicted requiring a significantly longer median treatment duration to achieve their peak FEV1 response compared with those patients with a baseline FEV1 between 40% and 69% predicted (8.0 versus 9.9 days, P = 0.041) (Figures 2 and 3B).

Figure 2.

Treatment duration and time to peak response by subgroups. Box and whisker plots of antibiotic treatment duration (white boxes) and time to peak observed FEV1 measure (gray boxes) among patients stratified by antibiotic treatment (ceftaz/tobra and mero/tobra) and by lung disease stage (FEV1 ≥ 70% predicted, 40- 69% predicted, and <40% predicted).

Figure 3.

Time from antibiotic treatment initiation to peak FEV1 measure for subgroups. Panel A, Time to peak FEV1 measure stratified by antibiotic treatment assignment. Gray line, ceftaz/tobra; black line, mero/tobra; dotted line, population treatment duration. Panel B. Time to peak FEV1 measure stratified by baseline lung function. Gray line, patients with baseline FEV1 ≥ 70% predicted, black line, patients with baseline FEV1 between 40% and 69% predicted; dashed line, patients with baseline FEV1 < 40% predicted; dotted line, population treatment duration.

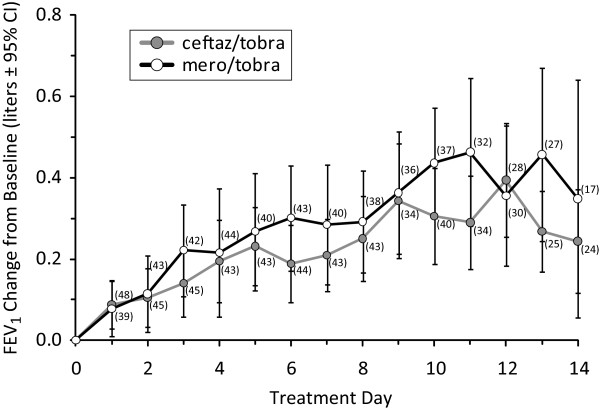

For the entire population, patients experienced an average peak increase in FEV1 of 0.55 liters, from a baseline average of 1.40 liters to a peak average of 1.95 liters (Table 2). In relative terms, patients experienced an average 47.2% increase over their baseline FEV1 at peak. Patients receiving mero/tobra experienced a greater average increase in FEV1 from baseline to their peak measure than patients receiving ceftaz/tobra (0.65 liters versus 0.46 liters; p = 0.033). However, when individual peak FEV1 increases were normalized for baseline FEV1 values, the 55.9% relative increase experienced by mero/tobra patients was not significantly different (p = 0.056) than the 39.3% relative increase experienced by ceftaz/tobra patients. Average peak increases in FEV1 were not significantly different for patients with different baseline lung disease stages, ranging from 0.51 liters to 0.70 liters (Table 2).

Table 2.

FEV1 Measures

| Subject Group | Mean, liters ± SD | Median, liters | Range, liters (min - max) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Baseline FEV1 |

|||

| All patients (n = 95) |

1.40 ± 0.71 |

1.19 |

3.09 (0.44 - 3.53) |

| ceftaz/tobra treated (n = 50) |

1.37 ± 0.71 |

1.13 |

3.09 (0.44 - 3.53) |

| mero/tobra treated (n = 45) |

1.44 ± 0.71 |

1.37 |

2.99 (0.48 - 3.47) |

| FEV1 ≥ 70% predicted (n = 11) |

2.46 ± 0.87 |

2.72 |

2.38 (1.15 - 3.53) |

| FEV1 40% - 69% predicted (n = 46) |

1.54 ± 0.56 |

1.47 |

2.52 (0.56 - 3.08) |

| FEV1 < 40% predicted (n = 38) |

0.93 ± 0.30 |

0.90 |

1.43 (0.44 - 1.87) |

|

Observed Peak FEV1 |

|||

| All patients |

1.95 ± 0.87 |

1.72 |

3.62 (0.67 - 4.29) |

| ceftaz/tobra treated |

1.83 ± 0.85 |

1.55 |

3.29 (0.67 - 3.96) |

| mero/tobra treated |

2.09 ± 0.88 |

1.78 |

2.99 (0.48 - 4.29) |

| FEV1 ≥ 70% predicted |

3.17 ± 1.01 |

3.71 |

2.99 (1.30 - 4.29) |

| FEV1 40% - 69% predicted |

2.05 ± 0.71 |

2.05 |

2.76 (0.84 - 3.60) |

| FEV1 < 40% predicted |

1.48 ± 0.59 |

1.39 |

2.44 (0.67 - 3.11) |

|

FEV1 Change, Baseline to Peak |

|||

| All patients |

0.55 ± 0.43 |

0.46 |

2.19 (0.0 - 2.19) |

| ceftaz/tobra treated |

0.46 ± 0.36 |

0.39 |

1.50 (0.05 - 1.55) |

| mero/tobra treated |

0.65 ± 0.49 |

0.55 |

2.19 (0.0 - 2.19) |

| FEV1 ≥ 70% predicted |

0.70 ± 0.46 |

0.43 |

1.40 (0.15 - 1.55) |

| FEV1 40% - 69% predicted |

0.51 ± 0.41 |

0.46 |

2.19 (0.0 - 2.19) |

| FEV1 < 40% predicted | 0.56 ± 0.45 | 0.43 | 1.93 (0.01 - 1.94) |

Discussion

There may be no more challenging aspect of CF exacerbation management than determining an "appropriate" or "optimal" use of systemic antibiotics [8]. In addition to the question of which organisms within complex multispecies lung infections should be targeted (and by extension, which specific antibiotics should be chosen), the question of how long antibiotics should be administered has yet to be meaningfully explored [8,12]. In the past, CF treatment guidelines have suggested that treatment duration should be determined empirically by "the improvement, or lack thereof" of pulmonary function [7]. This suggestion is logical, in that loss of FEV1 is a strong predictor of exacerbation diagnosis [6], and antibiotic therapy has been shown to significantly improve lung function in CF patients experiencing an exacerbation [11]. Unfortunately, many patients treated for a CF exacerbation do not fully recover lung function lost immediately prior to intervention [5], creating a dilemma for the treating clinician: if a patient has not fully recovered lost lung function following weeks of antibiotic treatment, should treatment be extended? At what point does the clinician accept that the patient will not fully recover lung function on the current regimen, and that continued antibiotic treatment may be futile and possibly deleterious?

The reasons that some patients fail to completely recover lost lung function following exacerbation [5] remain unknown. It may be that antibiotic choices and/or treatment durations made for some patients have been suboptimal, or simply that irreversible lung damage has occurred in some patients, or both. It can be argued, however, that an "optimal" duration for any antibiotic therapy would be one that includes an observed peak increase in FEV1, regardless of the magnitude of the increase observed. In practice, it is impossible to recognize that moment in time when a patient is experiencing his or her peak FEV1 improvement, as this is an inherently retrospective analysis. It is possible, however, to retrospectively review a series of treatment courses and ask whether the timing of peak responses adhere to a consistent pattern that could be useful in predicting future response time courses. Recently, a retrospective analysis of 1,535 patients treated for exacerbation while participating in the US CF Twin and Sibling Study between 2000-2007 showed that, on average, lung function recovery reached a plateau after 8 and 10 days of treatment [14] a result similar to that observed in a small prospective study by Regelmann et al. [11] two decades earlier. Our results compliment and expand on these earlier findings, in that we have been able to analyze daily PFT measures for individual patients to confirm that attainment of peak FEV1 occurs fairly consistently within 2 weeks of initiation of antibiotic treatment.

There are several limitations to the current analysis, not the least of which is that patients were not consistently treated for an extended duration (e.g., 3 or more weeks) in order to derive more accurate time to peak FEV1 response curves. It is possible that if all patients (and particularly those treated for the shortest durations) had been treated longer, they may have experienced higher peak FEV1 values later in treatment. For instance, the mean peak improvement in FEV1 for the 10 patients treated between 4 and 8 days was only 0.46 liters (median = 0.26, SD = 0.64 liters) (Table 3), lower than the population average of 0.55 liters (Table 2). However, only 2 of these patients experienced their peak FEV1 on their final day of treatment, and although the median treatment duration within this subgroup was 7 days, the median time to peak FEV1 response among these patients was only 4.5 days. Comparison of outcomes for the 43 patients treated between 9 and 13 days with the 42 patients treated for 14 days or longer suggests that little advantage was obtained by extended treatment, with 85.7% of patients treated for greater than 14 days experiencing their peak FEV1 before 14 days treatment (Table 3). Average peak FEV1 improvement trended lower in patients treated for more than 14 days compared to those treated for 9 to 13 days (0.50 versus 0.62 liters; P = 0.17). Average peak FEV1 improvement for the 8 patients treated for at least 16 days was 0.40 liters (median = 0.36, SD = 0.20 liters), with half experiencing their peak FEV1 by day 12. Although investigators may have extended the treatment of these patients on the basis of a poor initial FEV1 response, extending treatment did not result with these patients having a higher overall FEV1 response than others in the study.

Table 3.

Relationships between Treatment Duration and Observed Peak FEV1

| Treatment Duration Window |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 4-8 Days | 9-13 Days | 14+ Days | |

| Patients, n |

10 |

43 |

42 |

| Median Treatment Duration, days |

7 |

12 |

14 |

| Median Peak FEV1 Observation, days |

4.5 |

8 |

11.5 |

| Mean Peak FEV1 Increase, liters ± SD |

0.46 ± 0.64 |

0.62 ± 0.43 |

0.50 ± 0.38 |

| Patients Reaching Peak FEV1 before Duration Window, n (%) | 3 (30.0%) | 22 (51.2%) | 36 (85.7%) |

A caveat of this retrospective study is that patients had to have had at least one ceftazidime and meropenem susceptible strain of P. aeruginosa isolated from their respiratory secretions at baseline in order to be eligible for randomization [13]. Although it has been suggested previously that response to antipseudomonal antibiotics (and particularly to ceftazidime plus tobramycin) is independent of in vitro susceptibility test results in CF [15], it may be that time to peak FEV1 response may be impacted by the absence of antibiotic susceptible strains in patients experiencing an exacerbation.

It is not our intention to discourage treating physicians from diligently pursuing other treatable causes of failure to improve FEV1 to pre-exacerbation average or recent best FEV1 in patients who have experienced pulmonary exacerbation. However, these data suggest that continued application of a given antibiotic intervention beyond approximately two weeks is unlikely to result in additional patient benefit with respect to FEV1. Results from this retrospective analysis suggest hypotheses that might be tested in prospective CF exacerbation clinical trials. First, median times to peak FEV1 response for the two antibiotic treatments were not significantly different (Figures 2 and 3A) despite a suggestion of a difference in the magnitude of peak FEV1 response to each treatment (Table 2 and Figure 4). This result implies that antibiotic treatment duration and FEV1 response magnitude may be relatively independent, and that the magnitude of an antibiotic response is unlikely to be improved by extending treatment beyond 14 days. The profiles of mean daily changes in FEV1 from baseline through day 14 by treatment group are consistent with this hypothesis, in that the relative amplitudes of the profiles differ but their shapes are similar (Figure 4). A blinded study in which subjects are randomized to receive either 14 days of treatment or the current practice of extended treatment at clinician discretion [7] could address the question of whether additional benefit (or harm) is associated with extended treatment. Second, 89 of 95 patients (93.7%) experienced their highest FEV1 on or before day 13 of treatment, and only 12 (12.6%) patients experienced their peak FEV1 on their last day of treatment, including 7 who were treated less than 12 days. These results suggest that limiting treatment protocols to 14 days duration for the purposes of comparing responses to different antibiotic treatments would be both ethical and likely to detect true differences between treatments. Third, there was a noticeable trend with respect to the impact of baseline lung function on time to peak FEV1 response, with patients having a baseline FEV1 ≥ 70% predicted having a significantly shorter median time to peak response (7 days) when compared to patients with baseline FEV1 < 40% predicted (10 days, P = 0.041) (Table 1; Figures 2 and 3B). Interestingly, the magnitude of improvement in FEV1 (in liters) was fairly consistent across lung disease stages (Table 2). These results suggest that baseline lung disease stage should be accounted for in the design and analysis of prospective exacerbation studies. Finally, our analyses have necessarily been limited to the question of when peak FEV1 was observed during antibiotic treatment, but the implication that FEV1 increase following exacerbation is limited to that period when antibiotics are administered may not be justified. Unfortunately, subject spirometry after cessation of antibiotics was not available for this retrospective analysis, but a prospective trial of antibiotic treatment duration should consider the possibility that additional recovery of FEV1 may occur after antibiotic treatment is halted.

Figure 4.

Average daily change in FEV1 from baseline by treatment group. Gray circles, patients treated with ceftaz/tobra. Open circles, patients treated with mero/tobra. Sample sizes for measures are in parentheses.

Abbreviations Used

Ceftaz: ceftazidime; CF: cystic fibrosis; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; mero: meropenem; PFT: pulmonary function test; tobra: tobramycin

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JB was the principal investigator on the original randomized controlled trial. DV and MK conceived of the retrospective study and DV conducted the analyses and constructed the figures. MO provided data management support and reviewed/contributed to the statistical analysis plan. DV drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed to the revision and finalization of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Donald R VanDevanter, Email: enigmaster@comcast.net.

Mary A O'Riordan, Email: MaryAnn.ORiordan@UHhospitals.org.

Jeffrey L Blumer, Email: Jeffrey.Blumer@UHhospitals.org.

Michael W Konstan, Email: Michael.Konstan@UHhospitals.org.

References

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry: 2008 Annual Data Report. Bethesda, MD: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey BW. Management of pulmonary disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:179–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607183350307. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang L, Grosse SD, Amendah DD, Schechter MS. Healthcare expenditures for privately insured people with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44:989–96. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferkol T, Rosenfeld M, Milla CE. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations. J Pediatr. 2006;148:259–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.019. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders DB, Hoffman LR, Emerson J, Gibson RL, Rosenfeld M, Redding GJ, Goss CH. Return of FEV(1) after pulmonary exacerbation in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45:127–34. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin HR, Butler SM, Wohl ME, Geller DE, Colin AA, Schidlow DV, Johnson CA, Konstan MW, Regelmann WE. Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis. Pulmonary exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37:400–6. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Clinical practice guidelines for cystic fibrosis. Bethesda, MD: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Flume PA, Mogayzel PJ Jr, Robinson KA, Goss CH, Rosenblatt RL, Kuhn RJ, Marshall BC. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pulmonary Therapies Committee. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: treatment of pulmonary exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:802–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200812-1845PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wientzen R, Prestidge CB, Kramer RI, McCracken GH, Nelson JD. Acute pulmonary exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. A double-blind trial of tobramycin and placebo therapy. Am J Dis Child. 1980;134:1134–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1980.02130240018007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold R, Carpenter S, Heurter H, Corey M, Levison H. Randomized trial of ceftazidime versus placebo in the management of acute respiratory exacerbations in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 1987;111:907–13. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(87)80217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regelmann WE, Elliott GR, Warwick WJ, Clawson CC. Reduction of sputum Pseudomonas aeruginosa density by antibiotics improves lung function in cystic fibrosis more than do bronchodilators and chest physiotherapy alone. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:914–21. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.4_Pt_1.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes BN, Plummer A, Wildman M. Duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy in people with cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008. p. CD006682. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Blumer JL, Saiman L, Konstan MW, Melnick D. The efficacy and safety of meropenem and tobramycin vs ceftazidime and tobramycin in the treatment of acute pulmonary exacerbations in patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2005;128:2336–46. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaco JM, Green DM, Cutting GR, Naughton KM, Mogayzel PJ. , JrLocation and duration of treatment of cystic fibrosis respiratory exacerbations do not affect outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Smith AL, Fiel S, Mayer-Hamblett N, Ramsey B, Burns JL. Susceptibility testing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates and clinical response to parenteral antibiotic administration: lack of association in cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2003;123:1495–1502. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.5.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]