Summary

Quality improvement programs for depression in primary care can reduce disparities in outcomes. We describe how community-partnered participatory research was used to design Community Partners in Care, a randomized trial of community engagement to activate a multiple-agency network versus support for individual agencies to implement depression QI in underserved communities.

Keywords: Major depression, quality improvement, community-based participatory research, health disparities, intervention studies, minority health

Community…is… about where you live – where there are lots of diverse people — some you like, some not – but you have to respect them all.

—Participant at dinner sponsored by QueensCare Health and Faith Partnership

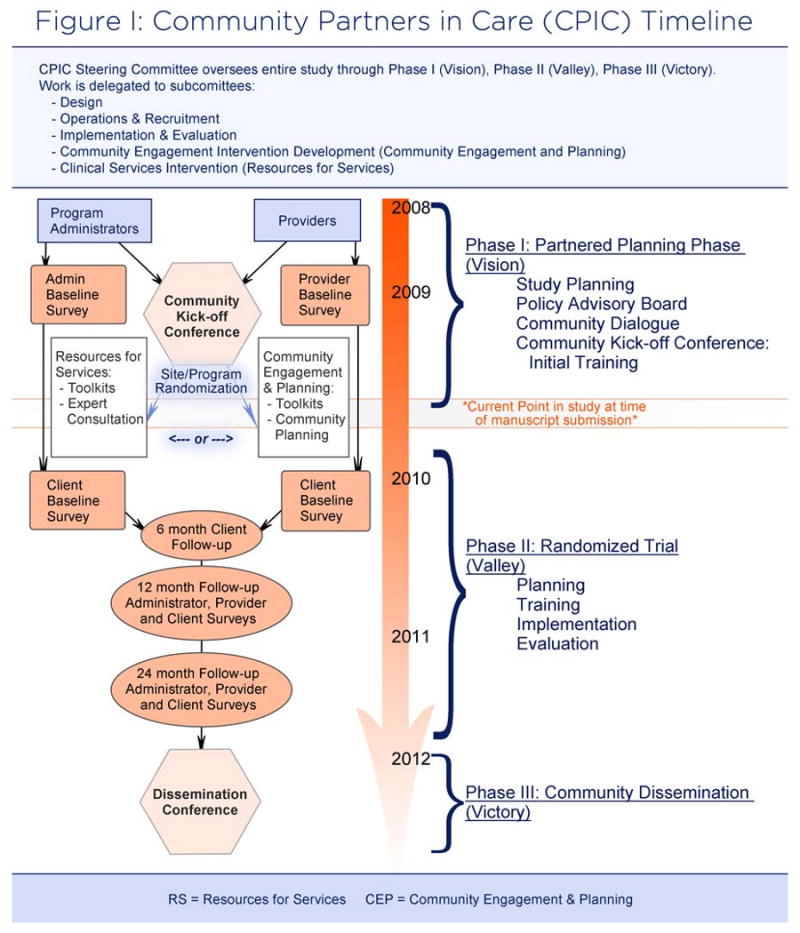

Depression is a common health condition, associated with limitations in multiple domains of daily functioning.1-4 Minority groups have lower rates of appropriate care for depression than Whites.5-12 There are evidence-based programs based on the collaborative care model that improve quality of care for depressed primary care patients. The Partners in Care study found such programs can improve health outcomes for minorities over 5-10 years, leading to reducing outcome disparities relative to Whites, in addition to improving employment over two years.13-18 Implementation of these interventions is challenging in underserved urban communities due to limited resources.19 To explore how to promote implementation of such programs to improve depression care in underserved communities, a community-academic partnership was established based on the principles and structure of community-partnered participatory research (CPPR). CPPR is a variant of Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) that emphasizes true power sharing and collaboration in all phases of research.20 CBPR is a well-established approach recommended as a method to address health disparities by enhancing trust in research and engaging minorities around health issues.21-26 The CPIC study is designed to reflect the three phases of a CPPR initiative (Figure 1).29-32 Such a partnership led to the Witness for Wellness (W4W) initiative, a large intervention development project to develop community-driven strategies to reduce stigma, improve services quality, and promote policies to reduce the burden of depression in South Los Angeles.27-31 W4W demonstrated underserved, urban minority community members view depression as an issue of collective concern, particularly when information is presented using culturally relevant approaches, such as the arts.27,31 There are few randomized trials of community engagement compared with other strategies 32-34 and none that we are aware of attempting to improve depression care or outcomes in underserved communities.

Figure 1. Timeline for CPIC [author: all figures must be provided in black and white].

In this paper, we describe the design-planning phase (Vision) of a randomized trial, Community Partners in Care (CPIC), which like W4W was also conducted using CPPR principles and structure. At the time of writing this article, the study is transitioning to the implementation of the trial itself (Valley).

The randomized trial, CPIC, compares a low impact intervention, Resources for Services (RS) with a CPPR planning process, Community Engagement and Planning (CEP), as approaches to implement depression care in agencies and programs. The study assesses the impact of the different implementation approaches on community agency administrator, provider and client outcomes for depression. Both RS and CEP groups are exposed to an initial conference that trains recruited agencies, programs, and providers in the CPIC toolkit, consisting of components found in a depression collaborative care model, which includes care management support, medication management training, cognitive behavioral therapy, and administrator support for implementation. RS adds to the initial community conference by providing four, 90 minute technical assistance phone calls to agency administrators and providers on how to implement elements of collaborative care for depression in their agencies. CEP initiates a community planning process to develop a community wide plan for depression care, based on the materials presented at the initial CPIC Conference. The elements of a community plan for depression care are: screening, patient education, care management, and referrals for medications and therapy.

CPPR

CPPR has a structure, a set of principles, and a staged implementation approach assuring equal participation and leadership of community and academic partners while promoting capacity development and productivity. The structure consists of a steering council of relevant stakeholders, co-chaired by community and academic leaders. The council supports several workgroups that develop and implement action plans, approved by broader community input through large community forums. This structure facilitates respect for community and academic expertise ensuring Community Engagement principles (e.g., power-sharing, mutual respect, two-way capacity building) are integrated with scientific rigor. Much effort in a CPPR initiative is spent building and maintaining relationships through sharing perspectives and joint activities. Both partnership structures and principles are reinforced in a memorandum of understanding signed by all partners. CPPR initiatives have three phases. The CPIC study is designed to reflect the three phases of a CPPR initiative (Figure 1).35-44

Phase one is the partnered planning of the initiative (Vision), the subject of this article. Phase two is the randomized trial (Valley), which from a community perspective is a pilot to determine what works in the community. Phase three is the initiation of community dissemination beyond agencies in the trial phase based on a partnered analysis of the trial's results (Victory). Each phase has a cycle of activities that we refer to as the plan-do-evaluate cycle.

The community engagement intervention uses a W4W-like structure and set of principles to develop community-based strategies to implement the same toolkits in a culturally appropriate manner. We planned to recruit 60-80 agencies/sites across South Los Angeles and Hollywood-Metro Los Angeles. From these sites, we planned to recruit 60-100 administrators, 150-200 providers. We proposed to approach 6,000 clients in those agencies about being screened for depression, and planned to enroll about 500 that screened as potentially having depression. We plan to examine quality of depression care and depression outcomes at six months for clients and changes in use of toolkits, depression resources and services provision, and attitudes and knowledge about depression care, at 12 and 24 months for providers and administrators.

Leadership structure

The leadership body for the design phase was the CPIC Steering Council, which comprises community-based agencies and academic institutions that agreed to provide the leadership for the initiative. Council members for the Vision phase are listed in the Acknowledgements. The lead academic partners for this initiative were RAND Health (RAND) and the UCLA Health Services Research Center (UCLA). The lead community partners were Healthy African American Families II (HAAF), QueensCare Health and Faith Partnerships (QHFP), the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health (LAC DMH), and Behavioral Health Services. All study decisions are considered and voted upon by the CPIC Steering Council which meets twice monthly, communicating via conference and e-mail as needed.

The CPIC Steering Council focuses on study goals, project oversight and planning, budget allocation, and partnership development. Much of the work for CPIC is delegated to subcommittees of academic and community partners. The CPPR working groups for the Vision (design) phase were the CPIC Council's design committees. The CPIC committees, meeting frequency, and tasks are summarized in Box 1.

All study protocols were approved by the RAND Institutional Review Board (IRB) including the documentation of the Vision phase. UCLA deferred review to RAND under a joint IRB deferral memorandum of understanding.

Community input into CPIC design

Box 2 summarizes elements of the CPIC design, highlights input from community members (through Council or committee meetings, or the broader community dialogue or policy board input) and describes design adaptations approved by the Council.

Study measures

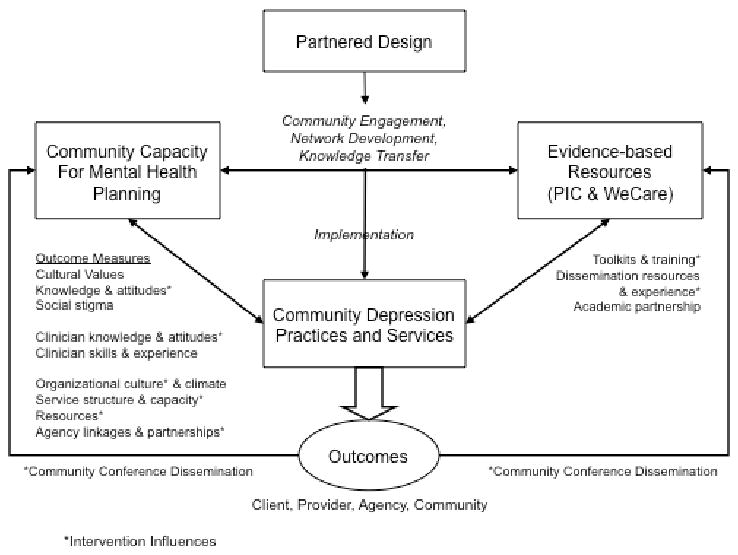

The study data are from administrators, providers, and clients; they were collected at baseline and two follow-up time points (6 and 12 months for clients; 12 and 24 months for providers and administrators). The study obtained qualitative data on implementation from meeting minutes, items within the main surveys, and other sources (see Figure 1). A summary of key constructs for client, organizational, implementation, and provider measures is found under “Community Capacity for Mental Health Planning” in Figure 2. Council community leaders interest in sustainability of change at the organizational level led to a proposal to add a wave of administrator and provider surveys (changing outcome from 18 months to 12 and 24).

Figure 2. Framework for Partnered Design, Community Engagement Implementation and Dissemination of Evidence Based, Quality Improvement.

Randomized trials designed under CPPR can enhance relevance and community ownership while maintaining scientific rigor. Over the last six years, our community-academic partnership developed the design for a randomized comparison trial, using a CPPR approach. Our partnership strove to develop the study to improve the quality of data to inform community planning about how best to improve services for depression in underserved communities and to provide data to the scientific community on the effectiveness of community engagement as an intervention strategy to promote evidence-based care for depression. We found that using a CPPR approach in the design phase (Vision) led to many changes in study design that potentially improve the fit of the study with community priorities (e.g., aligning community boundaries with existing county service planning areas), as well as enrich the study's potential scientific contributions (e.g., through expanded outcomes of community and policy relevance). Moreover, some of the changes, such as shifting the time of randomization to after the kick-off conference introducing the clinical intervention toolkits, improved internal validity by removing a potential source of bias (knowledge of intervention assignment, which could have led to differential conference attendance by intervention condition).

The strengthening of the study's overall focus on community engagement across intervention conditions, while potentially reducing the difference between intervention conditions, has improved the community support for the study. At the time of manuscript submission, we are moving from the Vision (phase 1) to the Valley (phase 2) of this CPPR initiative. To date, we have recruited 110 agency programs and sites, having randomized 74 in South Los Angeles to the two study conditions.

Overall, the changes to the design and measures in response to community input improved the external validity of the study such as including more vulnerable populations (such as people who are homeless), enhancing its relevance for underserved communities, while increasing study scope and costs. By structuring the study to respond to community input regularly, this initiative attempts to fulfill its mission as a community capacity-building and program development activity.

The CPIC design is complex, including multi-level sampling and group-level randomization. Participation in the study places a considerable demand on participating agencies without directly compensating them for services in a declining economy. Even though the scope of the randomized phase of the study in any one agency is relatively small, the economic depression in California, with a record 11.2% unemployment rate, has severely strained safety-net agencies, many of which have lost staff and infrastructure support while facing increased community needs.45,46 Yet, we have learned while both participating and non-participating agencies are concerned about the implications of participation, most agree with the importance of the study goals and appreciate the spirit of collaboration offered in the project.

The CPIC study is community-owned, in that the community is contributing time and effort and is not directly compensated. Some design features, nevertheless, make CPIC a good fit with community priorities. For example, the study supports a choice-based model, in which agencies, providers, and clients are supported in deciding which depression treatments they prefer, if any. Participants can refuse to use any intervention resources and remain in the trial. This means the study will generate findings about the effects of feasible implementation strategies, a different goal than understanding the effects of optimal treatment under a strict protocol. Because of the community's risk-taking and investment in participation, we hope that the study findings will provide important information to the community about what their collaboration achieves in terms of client and community member outcomes.

Because it takes time to obtain partnership input, studies like CPIC take time to design and revise.20-25,29-32 Despite the greater complexity of decision making, the colead CPIC committee composition and structure makes the consideration and adjustment of study protocols feasible.

Our partnership's focus has been on clinical depression, a topic that has drawn a high level of interest from all community participants, some of whom have personal concerns about depression. These distinct voices add a personal urgency to the social justice perspective of CPPR, and motivate the partnership to work hard to achieve our goals. Cashman et al. suggested that including community partners in data analysis and interpretation can enrich insights on the findings for academic and community partners.47 Building on this theme, we hope that participation of diverse stakeholders in the CPIC initiative yields findings supporting sustainable improvements in depression outcomes in our communities.48

Box 1: CPIC Committees, Meeting Frequency, and Tasks.

| Committee | Meeting Frequency | Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| Steering Council | 2 × / month | Study Goals Project oversight and planning Budget Allocation Partnership Development |

| Design | 2 × / month | Sampling Design Randomization procedures |

| Operations and Recruitment | 1 × / week | Day-to-day project management Agency, program, administrator, provider, client recruitment Survey administration and data collection |

| Implementation Evaluation | 2 × / month | Training and Conference Evaluation CEP Workgroup Evaluation Evaluation of agency implementation of CEP & RS Plans |

| Measures | As needed | Administrator, provider, and client survey development |

| Community Engagement and Planning | 1× / month | Development of CEP manual for use in CEP Workgroups Oversees CEP workgroups, CEP plan development and CEP trainings |

| Clinical Services Intervention | As needed | Oversees PIC training and supervision for administrator and providers (cognitive behavioral therapy, medication management, care manager) |

Box 1: Adaptations to Design Based on Community – Academic Partnered Solutions.

| Design Component | Original Study Goal | Community Feedback | Partnered Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study Goals | To demonstrate effectiveness of a community engagement and planning approach to disseminating evidence-based programs to improve depression care, versus technical assistance. | The win for agencies is not clear. Technical assistance suggests that study leaders are experts and not the community. | Study re-framed to offer two-way knowledge-exchange: 1) resources (academic and community) for individual agencies to improve services for depression; 2) those resources plus a mulit-agency community-academic planning process to promote sharing resources and adapting programs to the community to expand the reach of programs to all. We also emphasized the post-trial dissemination phase. |

| Sampling Design and Procedures | |||

| Definition of Community | Hollywood and South Los Angeles. | Base on Los Angeles County service areas but also follow clients along referral lines. | Expand to include full county service planning areas plus surrounding areas; study priorities for agency recruitment based on community knowledge of use and referral patterns; |

| Agency Sample | Primary care/community clinics, mental health clinics, Social service agencies | Expand locations to include “community trusted locations” | Expand to include churches and church health fairs, community centers and senior centres of parks and recreation, barber/beauty shops, women's gyms |

| Provider Sample | Service providers and case workers in recruited agencies | A range of leaders in the community and staff at agencies can influence clients | Expand to include faith-based leaders, community center program staff, staff at other community locations such as exercise clubs |

| Patient/Client Sample | Adults receiving services in established agencies. | Include the most vulnerable community members if possible and those not receiving services. | Agencies added that serve transitional age youth, elderly, homeless, and prison/jail release populations. |

| Randomization Procedure | Group-level (site, program, or clinical team as unit), randomized controlled (comparison) design with assignment to resources and encouragement for services (choice-based model); wait list for effective intervention at dissemination phase; randomization before kickoff conference | Choice-based model (agencies, providers, and clients are free to choose treatments or no treatment) and wait list for resources are valued types of design in the community. Acceptability of randomization in the community remains somewhat uncertain. | Provide clear explanations of this complex design (transparency). Involve community partners in implementing the randomization procedure. All respondents are free to participate or not as they choose. Those who do not want services or choose the treatments can remain in the study. Randomization will take place after kick-off conference. |

| Theory Basis of Intervention Implementation Evaluation | Diffusion of Innovation Theory, Quality improvement frameworks, Organizational Learning, Communities of Practice | Use community knowledge of services, practice, and populations; select theories that reflect the group or community values | Expand theory to include Collective Efficacy. Expand community input into concepts based on the principles of Community-Partnered Participatory Research. |

| Intervention Design | |||

| Resources for Services | Standard components of collaborative care for depression: Resources for primary care providers, nurse care managers, psychotherapists and counselors, patient education and activation, tracking and coordination, and team management/quality review | Resources are limited, especially primary care clinician time for training and services; few community clinics have available nurse or other trained staff for care manager roles | Train-the-trainers approach to training; identify potential community leaders for training early on. Simplify and clarify care manager materials for a range of staff levels |

| Community Engagement and Planning | Manual to guide use of action plans to review resources and adapt for agencies, plan trainings, and develop a collaboration plan | Communities of color may be reluctant to engage in more traditional or Western treatment models Many value alternative therapies Community-trusted locations such as parks do not have staff with clinical backgrounds; develop outreach. | Collaborate with community agencies to identify cultural competence resources Identify outreach models for mental health and supplement with locally-developed materials for diverse cultural groups |

| Outcome Measures (Clients) | See Figure One | Relevance of economic stress and strain with job losses Other outcomes of interest such as housing stability |

Expand to include employment status/workforce participation outcomes; and housing, recent victimization, and other common sources of stress in the community |

| Survey payments | Checks | Many community members do not use banks, and check cashing locations charge fees. | Cash or gift cards instead of checks. |

Box 2: Timeline of Intervention Planning and Training Activities.

| CPIC Kick-Off Conference (participants) | Timeframe | Activities | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| RS CEP | One day | Overview of CPIC materials | Introductory Materials: Improving Depression Outcomes in Primary Care: A User's Guide to Implementing the Partners in Care Approach (PIC); Training Materials: Training Agendas and Materials for Expert Leaders, Depression Nurse Specialists, and Psychotherapists, Videotape of Nurse Specialist Assessment; Materials for Primary Care Physicians & Care Managers: Clinician Guide to Depression Assessment & Management (PIC), Physician Pocket Reminder Cards, Guidelines/Resources for Depression Nurse Specialist (PIC); Psychotherapy Materials: Guidelines for the Study Therapist Group and Individual CBT Therapy Manuals for clinicians and clients (PIC, WE Care), Modified manuals for nurses, substance abuse counselors, and lay coaches; Materials for Patients: Patient Education Brochure in English and Spanish), Patient and Family Education Videotape (English and Spanish) including relapse prevention plan. All PIC / We Care materials have been culturally and linguistically adapted for African American and Latinos. |

| Resources for Services (participants) | |||

| RS | same timeframe as CEP Intervention (18 months) | Training resources from CPIC Kick-Off Conference and technical assistance follow-up phone calls on medication management, cognitive behavioral therapy, care management | |

| Community Engagement and Planning Orientation (Participants) | |||

| CEP | Two hours | Introduction to goals and resources of intervention condition | CEP Manual, Sample Action Plans, CPIC Organizational Plans |

| Community Engagement and Planning Workgroups (Participants) | |||

| CEP | Two meetings per month for Four to Five months | Workgroups will develop a written plan for coordinated delivery for depression for implementation in the pilot phase. | In addition to the materials in CEP orientation, the workgroups will receive administrative support and small pilot funds to develop plans. |

| Community Engagement and Planning Training (Participants) | |||

| CEP | One day – to be modified by the CEP workgroups | Training based on CEP workgroup planning and adaptation of materials from PIC / WE Care | Community Plan and Adapted materials from Initial CPIC Kick-off Conference |

| Pilot Implementation (Participants) | |||

| CEP | One year | Refine Interventions based on feedback from agency administrators, providers, community leaders, community members, and patients. | Outcome measures of successful implementation (providing supervision of therapy models such as cognitive behavioral therapy, new outreach roles, adjustments to collaboration agreements) |

| Community Dialogue | |||

| RS CEP |

One day | CPIC Council and Policy Advisory Board | Comparisons of CEP and RS interventions; Discussions of findings; Recommendations for community-wide plan for reducing impact of depression in the community; Sharing of testimonials from leadership of interventions conditions. |

| Community Dissemination | |||

| RS CEP |

CPIC Council and intervention working groups | CPIC plan for dissemination of study findings and resources. |

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest: The study investigators have no financial conflicts of interest to report.

Appendix Table One: Outcome Measures

| Potential Client Measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Client Characteristics | Process of Depression Care | Outcomes of Care | |

| Sociodemographics (0) | Assessment a | *Depression diagnosis (0) | |

| Insurance status (0,6,12,24) | *Current symptoms | *Depressive symptoms (0,6,12,24) | |

| Family members (0,6, 12,24) | Previous episodes | Household or work productivity (0,6,12,24) | |

| †Physical comorbidities | *Suicidal ideation | *Physical and Emotional functioning | |

| †Psychiatric comorbidities | *Substance use | (0,6,12,24) | |

| †Lifetime schizophrenia, †hospitalization for psychosis(0) | *Probable depression (0,6,12,24) | ||

| † One year | Treatment | Treatment compliance (0,6,12,24) | |

| PTSD screener (0) | *Use of psychotropic medications (0,6,12,24) | Satisfaction with treatment (6,12,24) | |

| Panic screener (0, 6, 12,24) | Treatment at index visit (0) | *Unmet Need (6,12,24) | |

| Alcohol screener (0, 6, 12,24) | *Primary care counseling (0,6,12,24) | ||

| Use of illicit substances (0) | *Specialty care referral and | ||

| Stressful life events (0,6, 12,24) | counseling (0,6,12,24) | ||

| Social supports (0) | Prior treatment (0) | ||

| Active/passive coping (0,6, 12,24) | |||

| Ethnicity/acculturation (0) | |||

| Depression knowledge (0,6) | |||

| Stigma concerns (0) | |||

| Treatment Preferences (0,6) | |||

| Readiness for treatment (0) | |||

| Organizational Measures (baseline,1st, 2nd, 3rd follow-up administrator/clinician surveys as indicated below) | |||

| Organizational Background | Services | Resources | Inter-Agency Linkages & Partnerships |

| Structure & Capacity | |||

| *Organization typea | *Services offeredc | *Fundingc | *Inter-agency linkages d |

| *Ownership/legal statusa | *Client size and compositionc | Staffing levelsc | Experiences & interest in partneringd |

| Organizational structurea | *Staff qualifications for depression cared | Physical space Information technologyc | Perceived barriers to partneringd |

| Organizational | *Experience with depression QI interventionsc | ||

| Culture & Climate | |||

| *Mission and prioritiesb | |||

| Receptivity to innovationb | |||

| Support for QIb & *PIC/WE Care interventionsd | |||

| Implementation Measures | |||

| Group dynamics of partnership | Exposure to training materials and roles | ||

| *Perceived level of participation | *Implementation activities | ||

| Communication & decision-making process | *Model adaptation | ||

| *Perceived level of trust | *Clinical use of PIC/WE Care | ||

| Intermediate partnership effectiveness | *Perceptions of PIC/WE Care interventions | ||

| Perceived accomplishments | Expansion of implementation/intent to spread | ||

| *Perceived empowerment & ownership | |||

| *Network development | |||

| Provider Measures and Timeframe (baseline-0, 12,24,36-month follow-up) | |||

| Occupation background (0) | *Depression treatment practices (0, 12, 24, 36) | Depression treatment proclivity (0,12,24,36) | |

| Demographics: Age, gender, ethnicity (0) | *Depression treatment knowledge (0, 12,24,36) | Readiness to change (0, 12, 24, 36) | |

| Workload (0) | Quality improvement experience (0, 12,24,36) | Perceived barriers to treatment (0, 12, 24, 36) | |

| Skill level with depression services (0, 12,24,36) | Satisfaction with work environment (0, 12, 24 36) | ||

Indicates priority measures.

0=baseline or screening, 6 or 12 = followup month.

available from CPI study or agency recruitment phase and highly stable;

assessed at baseline only and highly stable;

assessed at baseline, moderately stable and updated at baseline and 3rd follow-up.

assessed at all waves and related to implementation measures

References

- 1.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007 Sep 8;370(9590):851–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004 Jun 2;291(21):2581–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young AS, Klap R, Shoai R, Wells KB. Persistent depression and anxiety in the United States: prevalence and quality of care. Psychiatr Serv. 2008 Dec;59(12):1391–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.12.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):603–13. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook BL, McGuire T, Miranda J. Measuring trends in mental health care disparities, 2000 2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2007 Dec;58(12):1533–40. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagomasino IT, Dwight-Johnson M, Miranda J, et al. Disparities in depression treatment for Latinos and site of care. Psychiatr Serv. 2005 Dec;56(12):1517–23. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.12.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stockdale SE, Lagomasino IT, Siddique J, McGuire T, Miranda J. Racial and ethnic disparities in detection and treatment of depression and anxiety among psychiatric and primary health care visits, 1995-2005. Med Care. 2008 Jul;46(7):668–77. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181789496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi DT, Hong S, et al. Use of mental health-related services among immigrant and US-born Asian Americans: results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. Am J Public Health. 2007 Jan;97(1):91–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, et al. Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatr Serv. 2002 Dec;53(12):1547–55. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neighbors HW, Caldwell C, Williams DR, et al. Race, ethnicity, and the use of services for mental disorders: results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 Apr;64(4):485–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miranda J, Schoenbaum M, Sherbourne C, Duan N, Wells K. Effects of primary care depression treatment on minority patients' clinical status and employment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:827–834. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, et al. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:57–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells K, Sherbourne C, Duan N, et al. Quality improvement for depression in primary care: do patients with subthreshold depression benefit in the long run? Am J Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;162(6):1149–1157. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression: results of a group-level randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004 Apr;61(4):378–386. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Duan N, Meredith L, Unützer J, Miranda J, Carney MF, Rubenstein LV. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000 Jan 12;283(2):212–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Miranda J, Tang L, Benjamin B, Duan N. The cumulative effects of quality improvement for depression on outcome disparities over 9 years: results from a randomized, controlled group-level trial. Med Care. 2007 Nov;45(11):1052–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31813797e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel KK, Butler B, Wells KB. What is necessary to transform the quality of mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006 May-Jun;25(3):681–93. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallerstein N. Commentary: Challenges for the Field in Overcoming Disparities Through a CBPR Approach. Ethn Dis. 2006 Winter;16(1 Suppl 1):S146–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Garlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, Rhodes S, Samuel-Hodge C, Maty S, Lux L, Webb L, Sutton SF, Swinson T, Jackman A, Whitener L. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2004 Aug;:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7:312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seifer SD. Building and sustaining community-institutional partnerships for prevention research: findings from a national collaborative. J Urban Health. 2006;83:989–1003. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9113-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institute of Medicine. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies From Social and Behavioral Research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung B, Corbett CE, Boulet B, et al. Talking Wellness: a description of a community-academic partnered project to engage an African-American community around depression through the use of poetry, film, and photography. Ethn Dis. 2006 Winter;16(1 Suppl 1):S67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones D, Franklin C, Butler BT, et al. The Building Wellness project: a case history of partnership, power sharing, and compromise. Ethn Dis. 2006 Winter;16(1 Suppl 1):S54–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bluthenthal R, Jones L, Fackler-Lowrie N, et al. Witness for Wellness: preliminary findings from a community-academic participatory research mental health initiative. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(suppl 1):S18–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stockdale S, Patel K, Gray R, et al. Supporting wellness through policy and advocacy: a case history of a working group in a community partnership initiative to address depression. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(Suppl 1):S43–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung B, Jones L, Jones A, et al. Using community arts to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement as a means of addressing depression in an African American Community. Am J Public Health. 2009 Feb;99(2):237–44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141408. Epub 2008 Dec 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ammerman A, Corbie-Smith G, St George DM, et al. Research expectations among African American church leaders in the PRAISE! project: a randomized trial guided by community-based participatory research. Am J Public Health. 2003 Oct;93(10):1720–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pazoki R, Nabipour I, Seyednezami N, et al. Effects of a community-based healthy heart program on increasing healthy women's physical activity: a randomized controlled trial guided by Community-based Participatory Research (CBPR) BMC Public Health. 2007 Aug 23;7:216. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker EA, Israel BA, Robins TG, et al. Evaluation of Community Action Against Asthma: a community health worker intervention to improve children's asthma-related health by reducing household environmental triggers for asthma. Health Educ Behav. 2008 Jun;35(3):376–95. doi: 10.1177/1090198106290622. Epub 2007 Aug 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones L. Preface: Community-Partnered Participatory Research: How we can work together to improve community health. Ethn Dis. 2009 Autumn;19(1 Suppl 6):S6-1–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones L, Wells K, Norris K, Meade B, Koegel P. Chapter 1. The Vision, Valley, and Victory of Community Engagement. Ethn Dis. 2009 Autumn;19(1 Suppl 6):S6-3–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones L, Meade B, Forge N, et al. Chapter 2. Begin Your Partnership: The Process of Engagement. Ethn Dis. 2009 Autumn;19(1 Suppl 6):S8–1638. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones L, Meade B, Norris K, Lucas-Wright A, Jones F, Moini M, Jones A, Koegel P. Chapter 3: Develop a vision. Ethn Dis. 2009 Autumn;19(1 Suppl 6):S6-17–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones L, Meade B, Koegel P, Lucas-Wright A, Young-Brinn A, Terry C, Norris K. Chapter 4: Work through a plan. Ethn Dis. 2009 Autumn;19(1 Suppl 6):S6-31–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones L, Wells K, Meade B, Forge N, Lucas-Wright A, Jones F, Young-Brinn A, Jones A, Norris K. Chapter 5: Work through the valley: do. Ethn Dis. 2009 Autumn;19(1 Suppl 6):S6-39–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wells K, Koegel P, Jones L, Meade B. Chapter 6: Work through the valley: evaluate. Ethn Dis. 2009 Autumn;19(1 Suppl 6):S6-47–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones L, Wells K, Meade B. Chapter 7: Celebrate victory. Ethn Dis. 2009 Autumn;19(1 Suppl 6):S6-59–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones L, Koegel P, Wells KB. Bringing Experimental Design to Community-Partnered Participatory Research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Heatlh: From Process to Outcomes. 2nd. San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297:407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lifsher M, White RD. California unemployment rate reaches 11.2%. Los Angeles Times; Apr 18, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Decker c. Recession can be fatal for those too poor for insurance. Los Angeles Times; Apr 12, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cashman SB, Adeky S, Allen AJ, 3rd, Corburn J, Israel BA, Montano J, Rafelito A, Rhodes SD, Swanston S, Wallerstein N, Eng E. The power and the promise: working with communities to analyze data, interpret findings, and get to outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2008 Aug;98(8):1407–17. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113571. Epub 2008 Jun 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wells KB, Miranda J. Reducing the burden of depression. JAMA. 2007;298:1451–1452. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.12.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]