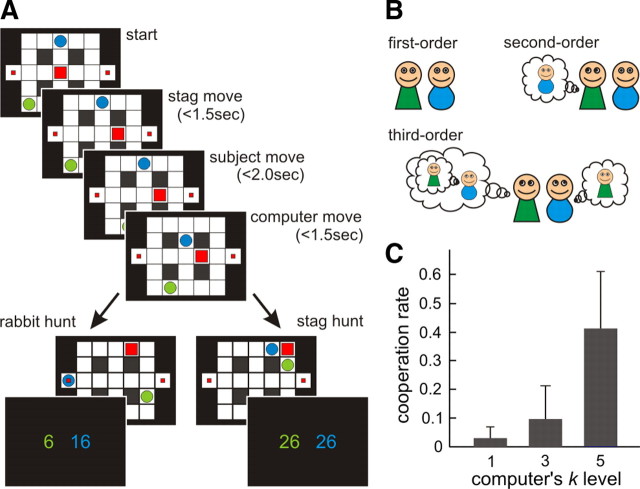

Figure 1.

Stag hunt game and theory of mind model. A, Two players (hunters), a subject (green circle) and a computer agent (blue circle), try to catch prey: a mobile stag (big square) or two stationary rabbits (small squares), in a maze. From an arbitrary initial state, they move to the adjacent states in sequential manner in each trial; the stag moves first, the subject moves, and then the computer agent moves. The players can capture either a small payoff (rabbit hunt; bottom left) or a big payoff (stag hunt, bottom right). Cooperation is necessary to hunt a stag successfully. At the end of each game, both players receive points equal to the sum of prey and points relating to the remaining time (see Materials and Methods). B, In our theory of mind model, the optimal strategies differ in the degree of recursion (i.e., sophistication): first-order strategies assume that other players behave randomly, second-order strategies are optimized under the assumption that other players use a first-order strategy, and third-order strategies pertain to an assumption that the other player assumes you are using a first-order strategy, and so on. Here, we assume bounds or constraints on the strategies available to each player and their prior expectations about these constraints. C, The subjects change their behavior based on the other player's sophisticated level (k) which was unknown. When the computer agents used fifth-order strategies, the rate of cooperative games (stag hunt) out of the total (mean ± variance = 0.405 ± 0.034) was significantly higher than when they used the lower third-order strategies (mean ± variance = 0.089 ± 0.012, p < 0.0001) and first-order strategies (mean ± variance = 0.026 ± 0.002, p < 0.00001).