Introduction

The evolutionary development of bacterial cell-to-cell communication, a process termed “quorum sensing” (QS), enabled coordinated behavioral efforts of bacterial populations, thus providing for microbial interaction with higher organisms. QS signaling defines the process of bacteria secreting and responding to small diffusible chemical signals, or autoinducers, in a cell density-dependent process.1 As the number of cells, and thus autoinducer concentrations, increase, bacteria synchronize their gene expression to behave as a unified group. These concerted efforts are beneficial to the bacterial population, but often come at the expense of human health, as QS has been shown to regulate functions such as biofilm formation and the expression of virulence factors. Consequently, the modulation of QS has emerged as a prophylactic and therapeutic anti-virulence target of considerable interest.2,3

QS signaling is mediated by autoinducing molecules that can be categorized into three major classes:4–7: i) N-acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs), ii) oligopeptides, and iii) autoinducer-2 (AI-2).8,9 AHLs are produced by many Gram-negative bacterial species, and signals are differentiated by acyl chain length and oxidation patterns. Likewise, oligopeptides, such as staphylococcal auto-inducing peptides (AIPs), are the signals employed by Gram-positive bacteria, and are often chemically posttranslationally modified. Lastly, the AI-2 class of signals is derived from the precursor 4,5-dihydroxy-2,3-pentanedione (DPD) and has been shown to signal in both Gram-positive and –negative bacteria. Because of the shared DPD core of the known AI-2 signaling molecules, and the ubiquity of the DPD synthase in the bacterial kingdom, AI-2 has been suggested as a language of interspecies communication. In addition to these three classes, other small molecules including the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS)10, 3-hydroxypalmitic acid methyl ester11, bradyoxetin12, and (S)-3-hydroxytridecan-4-one13 have also been identified. In general, individual species rely on chemically distinct signals to avoid interspecies cross-talk or interference. However, as discussed in this Perspective, the signals of one species often exert agonistic or antagonistic effects on the QS systems of other species.

Three main paradigms have been explored for the development of QS modulators as potential therapeutics: i) interference with the signal synthase, ii) sequestration of the autoinducer, and iii) antagonism of the receptor, with receptor antagonism having received the most attention to date for the discovery of QS modulators. Additionally, other modes of actions, such as prevention of signal secretion or inhibition of downstream signaling events, have also been examined. In this Perspective, we will focus on the third approach towards QS modulators, and review their development from a medicinal chemical perspective with a focus on the methods and rationale used for their discovery and/or design and synthesis. We will discuss agonists as well as antagonists of QS systems, and have included relative potencies (EC50values for agonists and IC50values for antagonists) where given in the original literature. In consideration of these values, it is important to state that strict comparisons may only be applied within a set of analogs examined in a particular assay, largely due to variations in reporter assays used for analog evaluation. Finally, we will discuss studies that have strived to establish QS as a viable target for the development of antimicrobial therapies.

AHLs

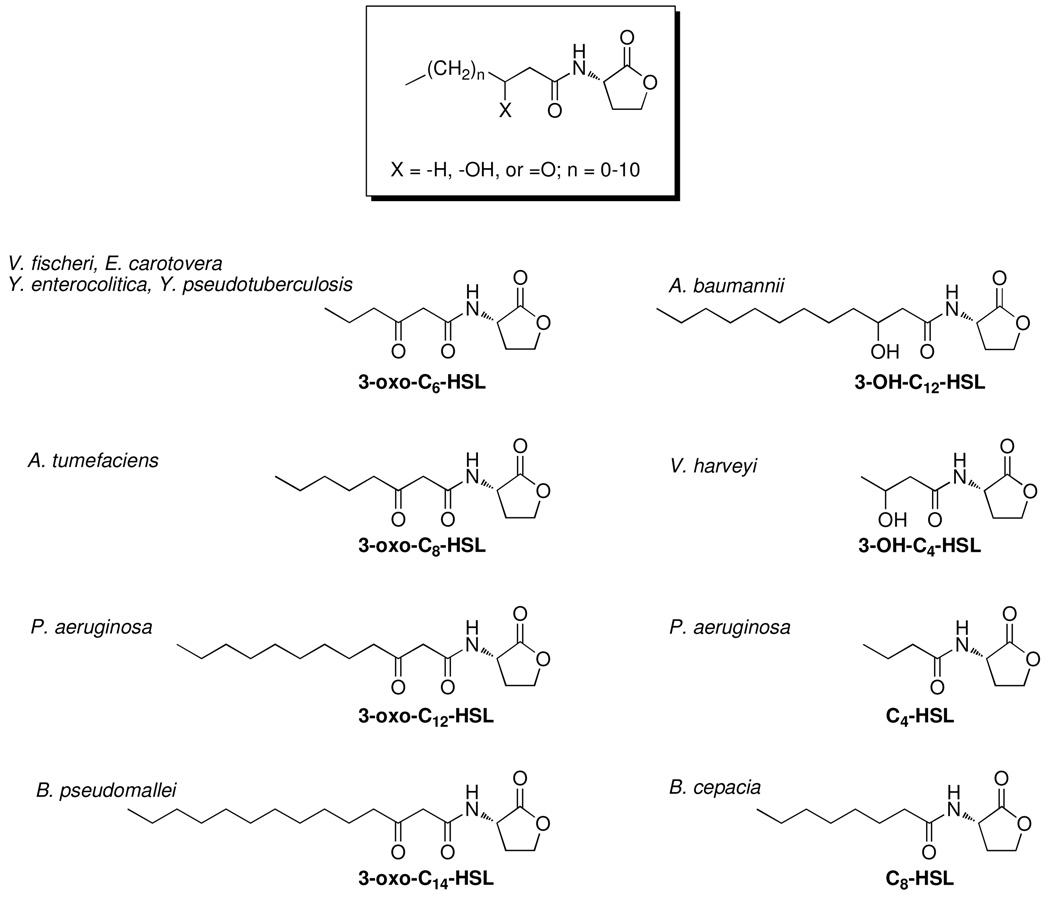

The best-studied QS circuits are the AHL-based systems employed by Gram-negative bacteria, and consequently, a variety of autoinducer analogs have been developed for this system. Historically, QS was first discovered in the marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri, which uses 3-oxo-C6-HSL to regulate the generation of its bioluminescence.14 In general, AHLs are synthesized from two metabolic intermediates, S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) and a fatty acid from the acyl-acyl carrier protein complex, in a reaction that is catalyzed by an AHL-synthase, also known as LuxI-type protein, named after LuxI in V. fischeri. Most AHLs diffuse freely across the bacterial cell membranes, but AHLs with extended acyl chains, such as the 3-oxo-C12-HSL signal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, might require active secretion into the environment.15 Upon reaching a critical threshold concentration, the AHL signal binds its target receptor protein, LuxR-type proteins, and this binding event, in turn, serves to activate the expression of target genes - in the case of V. fischeri, genes responsible for bioluminescence generation located on the lux operon. Interestingly, the initial discovery of QS-dependent bioluminescence regulation in V. fischeri was the first description of a group of bacteria acting in concert to achieve a common goal. Since this seminal discovery, several homologs of the LuxI- and LuxR-type proteins have been identified in other Gram-negative bacteria, such as the LasI/LasR proteins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the TraI/TraR proteins in Agrobacterium tumefaciens.16

A number of 3-oxo-AHLs have been shown to play an important role in processes involved in bacterial pathogenicity, particularly in the case of P. aeruginosa (Figure 1). This common environmental microorganism has acquired the ability to take advantage of weaknesses in the host defenses to become an opportunistic pathogen in humans.17 Most prominent is the role of P. aeruginosa in patients suffering from cystic fibrosis (CF), the most common inherited lethal genetic disorder, which follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern in Caucasian people. Approximately 30,000 people in the United States suffer from CF and due to impaired lung defense function, CF patients are vulnerable targets for P. aeruginosa.18 The QS machinery of P. aeruginosa coordinates the regulation of virulence factors, including elastase, rhamnolipids, and phenazines and also controls biofilm formation, which often has dire ramifications on human health, especially in the lungs of CF patients.

Figure 1.

General structure of the AHL signal and representative examples of naturally occurring signals.

The importance of QS to the virulence of P. aeruginosa is further demonstrated in a study of P. aeruginosa infections in burn wounds by the laboratory of Abdul Hamood.19 A mouse model was used to monitor the spread of the bacteria in burned skin as well as bacterial dissemination throughout the body, and P. aeruginosa mutants lacking QS machinery exhibited reduced spread. QS is also involved in the regulation of pathogenicity in many other human pathogens, such as clumping and motility in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis20 and Yersinia pestis,21 swimming and swarming motility in Yersinia enterocolitica,22 biofilm formation in Acinetobacter baumannii,23,24 virulence factor production in Burkholderia mallei,25 pathogenicity in Burkholderia pseudomallei,26 and protease activity and biofilm formation in the Burkholderia cepacia complex.27,28 Indeed, in several models of B. cenocepacia infection, including mammalian models, AHL-mediated QS was shown to play a central role in the control of pathogenic traits and was required for full pathogenicity in mouse and rat models.29,30 In this light, the potential for therapeutic intervention by targeting QS is evident; however, initial studies aimed towards the development of QS modulators mainly focused on the elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of the QS response.

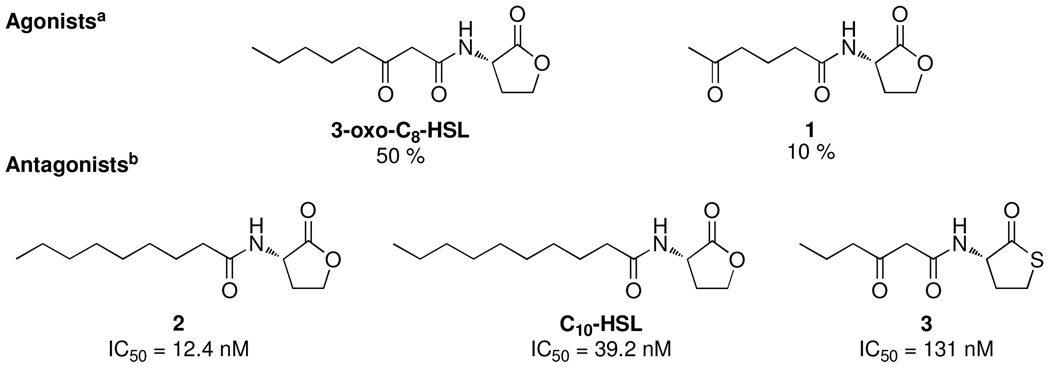

The earliest example of the development of QS modulators was reported over 20 years ago by Anatol Eberhard and coworkers in a study aimed at deciphering the mechanism of luminescence induction in V. fischeri.31 A panel of 19 compounds was synthesized, with variations in chain length and saturation, oxidation pattern at the 3 position, and composition of the lactone ring (Figure 2). From this panel of compounds both agonists and antagonists were identified, and surprisingly only slight variations from the structure of the parent autoinducer, 3-oxo-C6-HSL, produced profound changes in the observed bioluminescence. For example, extension of the carbon chain by 2 methylene units (3-oxo-C8-HSL) still produces 50% bioluminescence, whereas movement of the oxo-functionality from the 3 to 5 position (1) produces only 10% bioluminescence. Interestingly, compound 2 and C10-HSL exhibited minimal agonist activity, but powerful antagonist activity. The conversion of the lactone ring to thiolactone 3 also resulted in antagonistic activity (Figure 2). A similar set of compounds was evaluated as AHL analogs in Erwinia carotovora, which also uses 3-oxo-C6-HSL-dependent QS to regulate carbapenem biosynthesis.32 Again, similar trends were observed, as analogs with slight variations in acyl chain length or rings structure acted as agonists, albeit with diminished potency from the natural signal. From these trends, it was apparent that distinct chemical structures are necessary to induce full QS activity in different bacterial strains; however, it also became clear that small structural changes to the chemical scaffold of the natural autoinducers provide for widely variable biological activities.

Figure 2.

Representative examples of first AHL analogs developed by Eberhard et al.31 aPercentages represent light output induced by analog compared to the natural autoinducer. bConcentration of analog needed to reduce the activity of 46.8 nM of autoinducer to that of 23.4 nM.

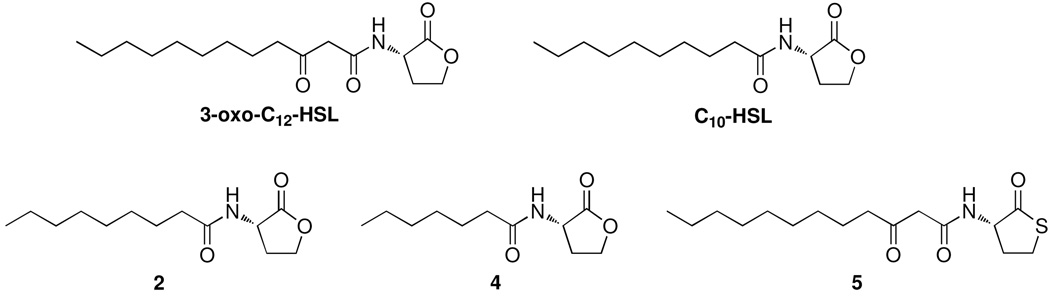

The interactions between AHL analogs and the LuxR receptor were later studied in greater detail using an expanded repertoire of analogs and a recombinant E. coli strain containing the QS-regulon of V. fischeri.33 In this work, the authors used a radiolabeled 3-oxo-C6-HSL analog to investigate the competition for LuxR between the analogs and parent AHL. Any analogs that were found to compete for LuxR binding were subsequently examined for either agonist or antagonist activity. Similar trends were observed with this panel of analogs as described previously by Eberhard et al.,31 in that the 3-oxo and lactone functionalities were required for productive LuxR activation, whereas acyl chains longer than 5 carbons resulted in antagonists of LuxR (Figure 3). These competition experiments, coupled with the QS activity of each analog, strongly supported the now-accepted hypothesis of a binding event between the AHL signal and the LuxR protein. Furthermore, the activity of these analogs was indicative of a certain degree of flexibility within the binding site of the LuxR receptor, thus providing a foundation for the development of more elaborate analogs.

Figure 3.

Examples of antagonists developed by Schaefer et al.33

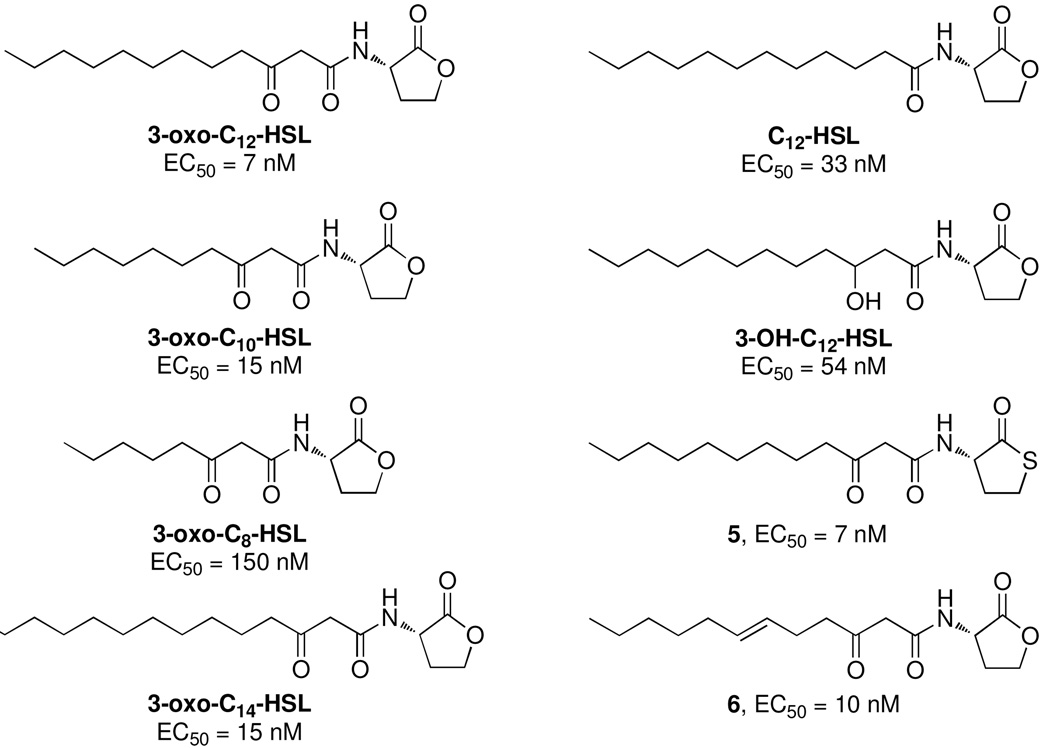

Around the same time, studies were underway in the laboratory of Barbara Iglewski to probe the binding of the P. aeruginosa AHL signal, 3-oxo-C12-HSL, to its cognate receptor LasR.34 A series of structural analogs with varying chain lengths, oxidation patterns, and heterocycle substitutions were synthesized via EDC-coupling of the sodium or lithium salt of the appropriate fatty acid chain with either the 2-amino lactone or amino thiolactone (Figure 4). These analogs were evaluated for agonist activity by monitoring the expression of a lacZ reporter fused to the QS operon of P. aeruginosa. The trends observed with these analogs were similar to those observed with the LuxR-AHL interactions, in that conservative variations of the 3-oxo-C12-HSL parent signal resulted in diminished receptor binding. Interestingly, C10-HSL, 2, and 5, which were found to be inhibitors of QS in V. fischeri (Figure 3), were discovered as agonists of QS in P. aeruginosa. Several antagonists against binding were uncovered in a competitive assay with radiolabeled 3-oxo-C12-HSL; however, no true inhibitors of QS were found, as all analogs that compete for LasR binding were also able to induce QS activity.

Figure 4.

Analogs of 3-oxo-C12-HSL designed to probe the binding interactions of LasR. EC50 values represent concentration needed for 50% activation of lasB.34

These early studies relied on simple analogs that focused on variations in acyl chain length, oxidation pattern, and substitution of the heteroatom in the ring to evaluate the critical functionalities of the AHL signals. Although these efforts did not reveal potent agonists or antagonists of QS, they were crucial in establishing, in principle, that bacterial communication may be modulated with synthetic analogs. Furthermore, these studies were also pivotal in instituting now-accepted concepts concerning signal-receptor interactions, namely the sensitivity of the cognate receptor to structural deviations of the signal. On the other hand, these changes, although rationally-designed from a chemical point-of-view, still provided for unpredictable biological effects.

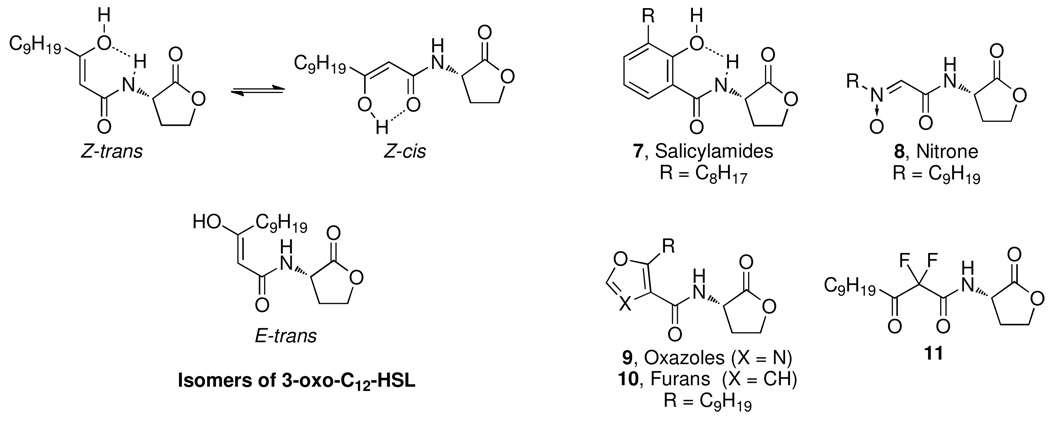

A departure from the standard development of AHL analogs described above was pursued via the synthesis of conformationally constrained analog reported by Kline et al.35 Whereas previous analogs had mostly centered on modifying acyl tail length while keeping the analogs themselves flexible, the authors of this study sought to explore the role of the various tautomers of the β-ketoamide moiety in the QS of P. aeruginosa. This was achieved using four series of compounds to evaluate the biological activity of the E and Z enols, as well as the extended form of the AHL signal. To mimic the Z form, salicylamide 7 and nitrone 8 frameworks were employed (Figure 5). On the other hand, simple heterocycles such as oxazoles 9 and furans 10 were introduced to emulate the E isomer. For the extended forms, gem-difluorosubstituted analog 11 was constructed to effectively prevent enolization and subsequent tautomerization. Compound 11, which displayed agonist activity, was the only active compound identified in this work, implying the necessity of proper acyl-tail geometry for LasR receptor binding. Despite the failure to uncover any analogs with potent activities, this work served to progress the development of AHL analogs past the previous reliance on minute, systematic changes to the AHL signal to incorporate novel chemical motifs.

Figure 5.

Isomers of 3-oxo-C12-HSL and the constrained analogs developed by Kline et al.35

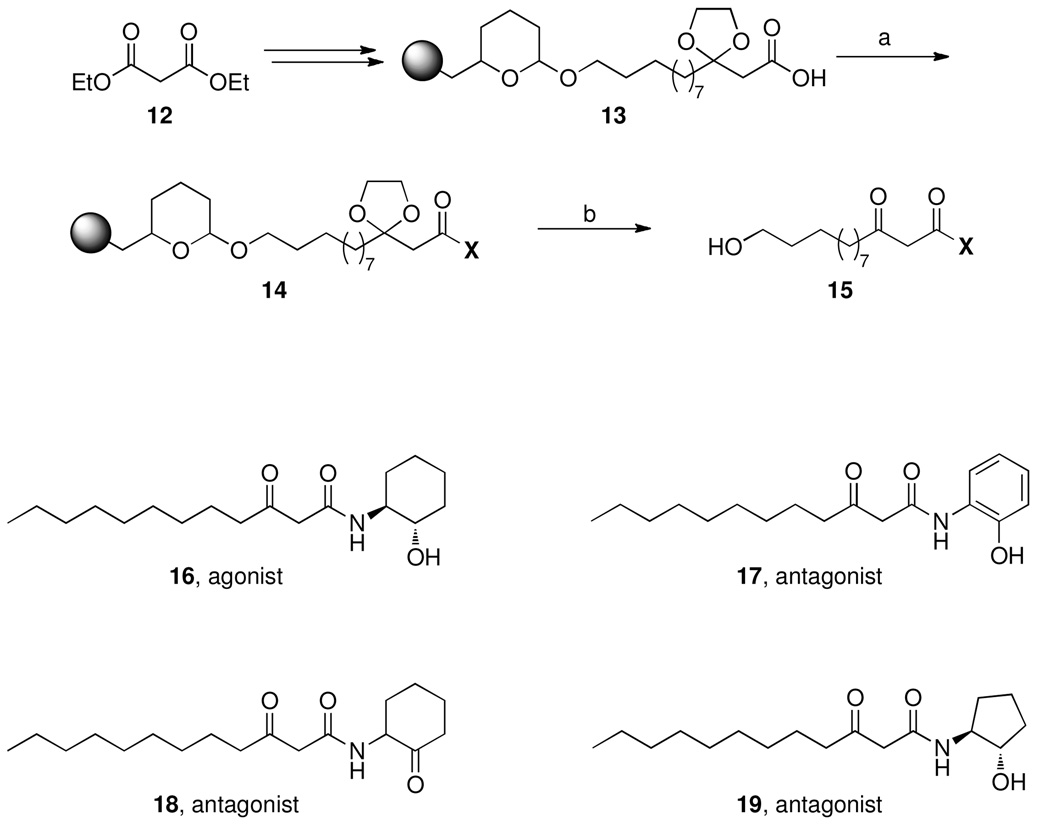

The group of Hiroaki Suga introduced another new paradigm for the discovery of AHL analogs with the synthesis of a library of analogs constructed via solid phase organic synthesis. In doing so, several agonists and antagonists of QS in P. aeruginosa were uncovered from a library of compounds that replaced the homoserine lactone functionality of the 3-oxo-C12-HSL signal with a variety of amines and alcohols. To rapidly generate a large panel of compounds, a solid phase approach was used in which the acyl chain was immobilized on a 3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran resin.36,37 To facilitate immobilization, the terminus of the acyl chain was modified to include a hydroxyl group. Previous work detailing the capacity of the LasR receptor to accommodate longer chains led the authors to reason that the increased length would have little effect on the biological activity. Once the acyl chain was immobilized on the resin, the ester was cleaved to reveal the carboxylic acid group (13), which then underwent reaction with a variety of aminoalcohols or amino ketones (14, Scheme 1). With compounds of type 14, treatment with acid provided for both deprotection of the ketone at the 3 position as well as cleavage from the resin.

Scheme 1.

Solid phase synthesis and representative examples of 3-oxo-C12-HSL analogs developed by the Suga group. Compounds were initially synthesized with a terminal –OH group, and lead compounds resynthesized as shown in 16–19.36,37

Reagents: (a) amine or alcohol, EDC, DMAP, DIPEA, DMF, rt, 72h. (b) 95% TFA, rt, 30 min.

With their library, compounds were evaluated for their activity against the QS of P. aeruginosa using a lasI-dependent gfp reporter assay. From the screening process, five agonists and eight antagonists were discovered, and, importantly, re-synthesis of these lead compounds without the terminal –OH group revealed that this modification did not interfere with the assay results. The series of (ant)agonists were initially identified and characterized using a gene-reporter assay; however, to evaluate the physiological effects of these new compounds, their effects on biofilm formation and the expression of the virulence factors elastase and pyocyanin were evaluated. Treatment of P. aeruginosa with the most potent antagonist (17) resulted in the reduction of elastase production and alterations in the biofilm architecture although actual biofilm levels were not reduced. A few interesting observations can be made from the activity of these analogs: (1) an aminocycloalkane with an H-bond donor at the ortho- position is a shared structural feature of the antagonists, and (2) a cyclohexanol-derived agonist 16 may be converted to an antagonist by simply replacing the cyclohexanol ring with a phenol 17, cyclohexanone 18, or cyclopentanol 19 (Scheme 1). These observations speak to a key advancement put forth by this work: the efficiency of a solid phase approach for the production of a large panel of analogs.

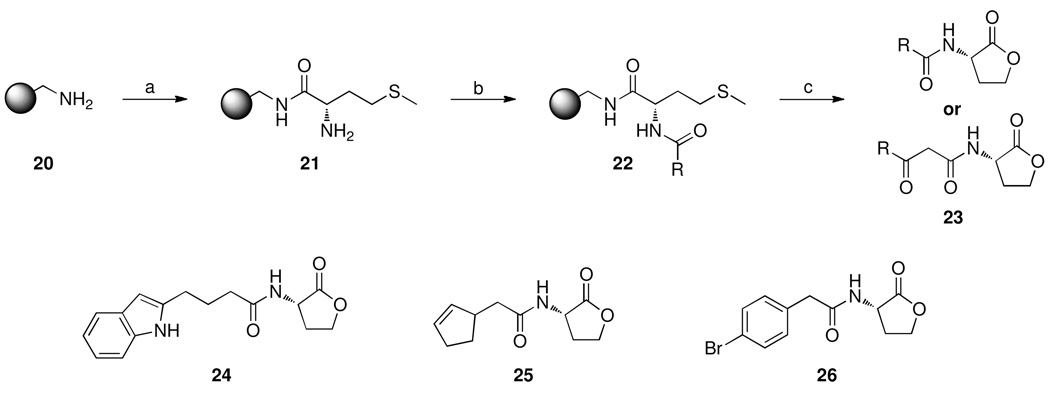

Two years later, Helen Blackwell and coworkers also exploited the power of solid phase synthesis with a series of investigations aimed at the systematic evaluation of non-natural AHL ligands. As a first step, a microwave-assisted solid phase synthesis was devised to provide rapid access to both natural and unnatural AHL analogs (Scheme 2).38 This newly developed synthetic route allows for the introduction of different acyl substituents, whereas the route developed by Suga and coworkers provided rapid access to diversity at the homoserine lactone functionality. The synthesis begins with the addition of methionine to polystyrene resin 20 to yield 21, followed by the introduction of various carboxylic or protected β-keto acids for the generation of diversity in the acyl chain (22). The analogs were then subjected to treatment with cyanogen bromide in a microwave assisted cyclization/resin cleavage reaction to provide the target analogs of type 23, which comprised both 3-oxo and non-3-oxo analogs. This new route was used to rapidly produce a variety of natural AHL signals in high purity, along with a panel of ~15 non-natural AHL analogs, which were subsequently tested, against QS-dependent reporter strains, for both agonist and antagonist activity by measuring β-galactosidase activity in Agrobacterium tumefaciens and GFP fluorescence in P. aeruginosa. The screening revealed three compounds (24-26) that were 1–2 orders of magnitude more potent than the known A. tumefaciens QS inhibitors and about 2-fold more active than known P. aeruginosa QS inhibitors (Scheme 2). Importantly, the inhibition of QS-dependent gene expression in P. aeruginosa by 24–26 also translated to significant activity against biofilm formation. The structural similarities of these new QS modulators suggested similar modes of binding by the receptor proteins of the two organisms studied and provided the Blackwell laboratory with a structural guide for the construction of a larger set of compounds for the study of QS across a range of bacterial species.

Scheme 2.

Solid phase synthesis and representative examples of AHL analogs developed by the Blackwell group.38

Reagents: (a) i) Fmoc-Met-OH, DIC, HOBT, CHCl3/DMF, MW 50 °C (2 ×10 min); ii) DMF, MW 150 °C, 7 min; (b) Various carboxylic / protected β-keto acids, DIC, HOBT, CHCl3/DMF, MW 50 °C (2 ×10 min); (c) CNBr, TFA, CHCl3/H2O, MW 60 °C, 30 min.

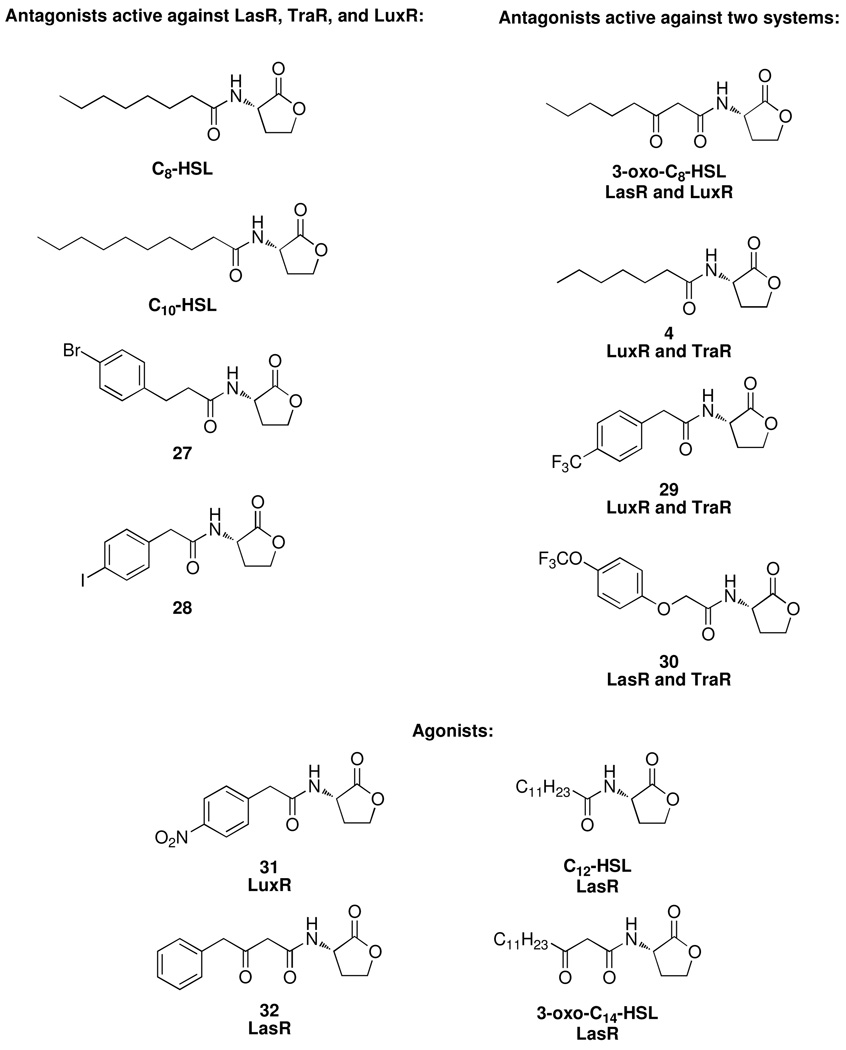

In a recent series of publications, Blackwell and coworkers continued to build upon their previous findings and synthesized another library (~90) of compounds and examined the activity across three bacterial species: A. tumefaciens, P. aeruginosa, V. fischeri.39,40 Rather than focus exclusively on bulky substitutions at the terminus of the acyl chain as before, this library also featured an expanded repertoire of compounds to probe the effects of both chain length and ring stereochemistry in addition to acyl chain substitution. As predicted, the screening of a large focused library revealed both antagonists and agonists against the three strains. One particularly interesting observation came in the discovery of 3-oxo-C8-HSL, the natural ligand for the A. tumefaciens TraR receptor, as a potent inhibitor against the QS of P. aeruginosa and a modest inhibitor against V. fischeri (although no IC50 value was reported), speaking to the potential for QS as a form of interspecies competition as well as cooperation. However, what sets this study apart is the discovery of antagonists (Figure 6 and Table 1) that are active against all three different bacterial species examined, thus allowing the authors to establish a detailed SAR of the active ligands. It should be noted that in the development of all AHL analogs to date, small structural changes to the parent AHL signal resulted in vastly different biological activities. Thus, the pioneering work of Suga and later Blackwell serve to demonstrate the power of efficient synthetic routes to introduce small structural changes to conduct SAR studies as well as the discovery of AHL-based QS modulators. Additionally, the design and synthesis of focused libraries has provided for the rational design and synthesis of haptens by our laboratory, which have been used to generate antibodies against the autoinducers of several bacteria.41,42

Figure 6.

Representative examples of AHL analogs active across multiple species.

Table 1.

IC50 (antagonists) or EC50 (agonists) values for compounds in Figure 6 against three bacterial strains. All values reported in µM. A blank entry indicates the value was not determined.

| Compound |

P. aeruginosa LasRa,d |

A. tumefaciens TraRb |

V. fischeri LuxRc,e |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antagonists | |||

| 3-oxo-C8-HSL | 0.11 | ||

| C10-HSL | 0.25 | 1.05 | 0.40 |

| 27 | 0.34 | 0.92 | 1.35 |

| 28 | 1.72 | 1.25 | 0.86 |

| C8-HSL | 1.75 | 0.77 | 0.77 |

| 30 | 4.67 | 0.46 | |

| 4 | 0.69 | 1.36 | |

| 29 | 0.81 | 0.61 | |

| Agonists | |||

| 3-oxo-C14-HSL | 0.01 | ||

| C12-HSL | 0.04 | ||

| 32 | 0.54 | ||

| 31 |

Antagonism assay performed using an E. coli LasR reporter strain in the presence of 7.5 nM 3-oxo-C12-HSL.

Antagonism assay performed using A. tumefaciens reporter strain in the presence of 100 nM 3-oxo-C8-HSL.

Antagonism assay performed using V. fischeri reporter strain in the presence of 5 µM 3-oxo-C6-HSL.

Agonism assays performed using the appropriate reporter strain in the absence of natural autoinducer.

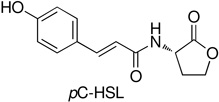

The work from the Blackwell laboratory also confirmed previous findings that the QS signals of one species may act as inhibitors against the QS of other species. Recently, a naturally occurring autoinducer was discovered in the soil bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris with structural similarities to the aryl-derived antagonists developed by Blackwell and coworkers. This new homoserine lactone signal, pC-HSL, is derived from p-coumaric acid rather than cellular fatty acids and reveals that natural homoserine lactone derived signals are not limited to straight chain acyl chains, but may also be comprised of aryl chains (Figure 7).43 Furthermore, two other species of bacteria, the plant symbiont Bradyrhizobium and the marine bacterium Silicibacter pomeroyi, were found to be capable of producing pC-HSL type signals, implying pC-HSL signaling across a wide variety of bacterial species. Structural similarities between pC-HSL and many of the aryl-based antagonists discovered by the Blackwell laboratory suggest a possible role for pC-HSL as an antagonist of the QS of other species; however, to date pC-HSL has not been tested for its activity against the QS of any other species. Such a finding would also speak to a deeper source of QS inhibitors, as the discovery of new QS signals in one species may also result in the discovery of new QS inhibitors against others species in the same manner that the discovery of new bacterial metabolites has produced a vast array of antibiotic compounds.

Figure 7.

Structure of pC- HSL

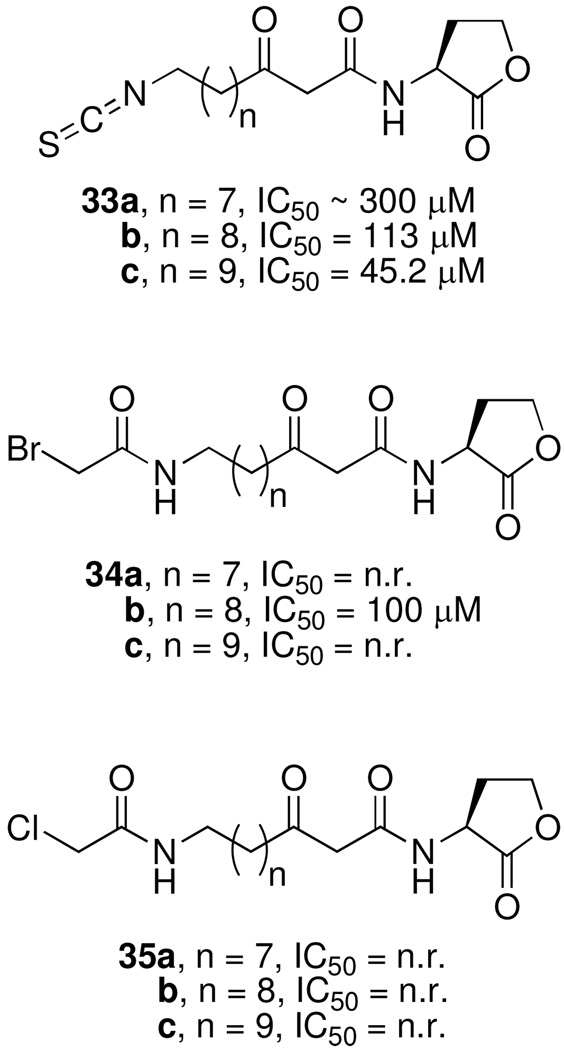

In a different approach, Michael Meijler and coworkers investigated a series of autoinducer analogs, designed with electrophilic functionality for the specific covalent modification of the target protein, with the goal of rendering the receptor protein unable to initiate the QS signaling cascade.44 For the design of the covalent probes, the authors took advantage of the high affinity and specificity of LasR for the natural ligand 3-oxo-C12-HSL and constructed structurally related compounds but containing a diminutive electrophilic group. The authors reasoned that a nucleophilic cysteine residue (Cys79) in the LasR binding pocket would serve as a reactive partner, and thus constructed a series of compounds with three electrophilic moieties: isothiocyanates 33, bromoacetamides 34, and chloroacetamides 35 (Figure 8). The capacity of the AHL-based probes to covalently modify LasR was first examined using purified LasR protein, and indeed, the isothiocyanate probes were found to react with Cys79. Importantly, these same compounds were found to inhibit QS in P. aeruginosa reporter strains, as well as decrease biofilm formation and pyocyanin production in wild-type strains, serving to establish these compounds as new motifs for the development of QS inhibitors. One concern that may arise from the use of electrophiles, including the brominated furanones (vide infra), to target QS stems from potential non-specific alkylation and resulting toxicity; however, in the case of these electrophilic AHL analogs, the authors examined only those concentrations for which no growth inhibition was observed.

Figure 8.

Analogs of AHL signals designed for the covalent modification of the LasR receptor protein. IC50 values represent activity against a luminescent P. aeruginosa reporter strain. (n.r. = not reported)

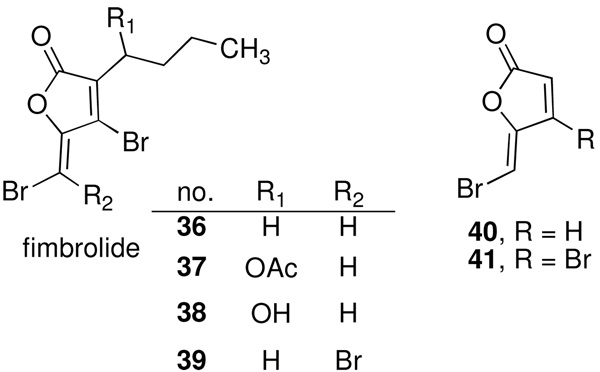

Natural products derived from eukaryotic sources have served as another source of QS disrupting compounds, and perhaps the most studied of these is the secretion of brominated furanones by the red algae Delisea pulchra. Although marine dwelling plants often suffer from macrofouling by higher organisms, usually caused by the initial formation of bacterial biofilms, D. pulchra was found to be relatively free from fouling organisms. Further microscopic analysis revealed bacterial populations to be reduced on the surface of D. pulchra relative to neighboring plants. A rationale for this observation has been provided by the laboratory of Staffan Kjelleberg, who demonstrated that the algae was releasing a series of brominated furanone metabolites which inhibit several AHL-dependent processes including swarming motility in Serratia liquefaciens and bioluminescence in V. harveyi and V. fischeri (36–39, Figure 9).45

Figure 9.

Structures of brominated furanones

Since their discovery, the activity of brominated furanones has been explored extensively, and naturally occurring furanones have also been found to inhibit AI-2-based QS in Vibrio sp. Because of structural similarities, the furanones were initially believed to compete with the natural AHL and AI-2 autoinducers for binding to their cognate receptors,46 but subsequent reports demonstrated that the halogenated furanones destabilize and accelerate turnover of the LuxR receptor in V. fischeri47 and inactivate the V. harveyi QS master regulator protein LuxRVh.46 Despite a common name, these two LuxR proteins have completely different functions, though it is likely that a similar mode of inhibition is at work based on the reactivity of the brominated furanones. These compounds possess multiple electrophilic centers capable of Michael addition at the α,β-unsaturated ketone, nucleophilic addition to the lactone carbonyl, or halogen substitution. Indeed, recent studies have indicated that the halogenated furanones undergo reaction with the DPD synthase, LuxS, likely through a Michael addition (vide infra).48 A common mode of action would be encouraging for the development of antimicrobial strategies against human pathogens, as homologs of LuxRVh from V. harveyi have been identified in the human pathogens V. cholerae, V. parahaemolyticus, and V. vulnificus. Thus, the prevalence of a common target implicates a potential for halogenated furanones as a broad spectrum inhibitor for the treatment of disease.46 However, it is the same broad reactivity, particularly towards alkylation, that is likely responsible for the toxic effects against mammalian cells that have been observed with this class of compounds.49,50

The reported utility of the furanone compounds also extends to the inhibition of QS in P. aeruginosa, and furanones have been shown to affect the siderophore biosynthesis of P. aeruginosa via interaction with the QS system,51 although minimal effects have been observed on the other QS phenotypes of P. aeruginosa.52 To overcome this limitation, screening of combinatorial libraries derived from the natural furanone structure has revealed furanones 40 and 41, both of which lack a hydrophobic side chain, with activity against the QS of P. aeruginosa (Figure 9).47,52,53 Using a GFP-expressing strain of P. aeruginosa, compound 40 was shown to specifically inhibit the las system, as well as the production of the virulence factors chitinase and elastase. Importantly, compound 40 was also capable of disrupting intercellular communication within P. aeruginosa biofilms, ultimately resulting in the loss of biofilm integrity and overall biomass.52 The utility of these QS inhibitors has also been extended to the study of unidentified QS regulated process, and towards this end furanone 41 was used in a series of GeneChip® microarray based studies to delineate both the QS regulatory network of P. aeruginosa and the effects of the furanone compound.53 Perhaps the most significant finding is the efficacy of compounds 40 and 41 against QS in mouse infection models. Mice with lungs infected by a QS-dependent gfpexpressing strain of P. aeruginosa were treated with these compounds, and in 4–6 hours a significant reduction in gfp fluorescence was observed relative to untreated controls. Inhibition of QS by 40 also corresponded to increased bacterial clearance from the lungs, as well as a 50% increased survival time of mice with lethal infections.54

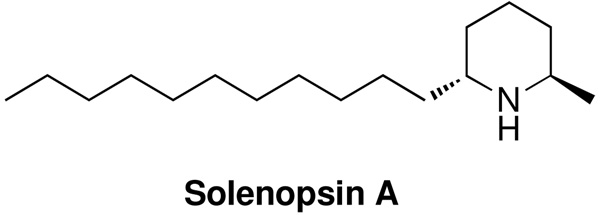

Another natural product that has shown promise against the QS of . aeruginosa is solenopsin A, a venom alkaloid from the fire ant Solenopsis invicta (Figure 10).55 Initially investigated due to structural similarities with the 3-oxo-C12-HSL signal and the antagonists developed by Suga et al (Scheme 1),36,37 solenopsin A was found to inhibit the production of the virulence factors pyocyanin and elastase B. When competition experiments were performed between the natural autoinducers of P. aeruginosa and solenopsin A, C4-HSL, rather than 3-oxo-C12-HSL, restored QS signaling. While other compounds, such as compound 23 developed by Suga et al. possess activity against both las and rhl systems,36 this represents a significant finding based on the relative lack of specific inhibitors against C4-HSL-dependent QS and as such solenopsin A may represent a valuable basis for the development of QS inhibitors against the rhl system of P. aeruginosa.

Figure 10.

Structure of solenopsin A.

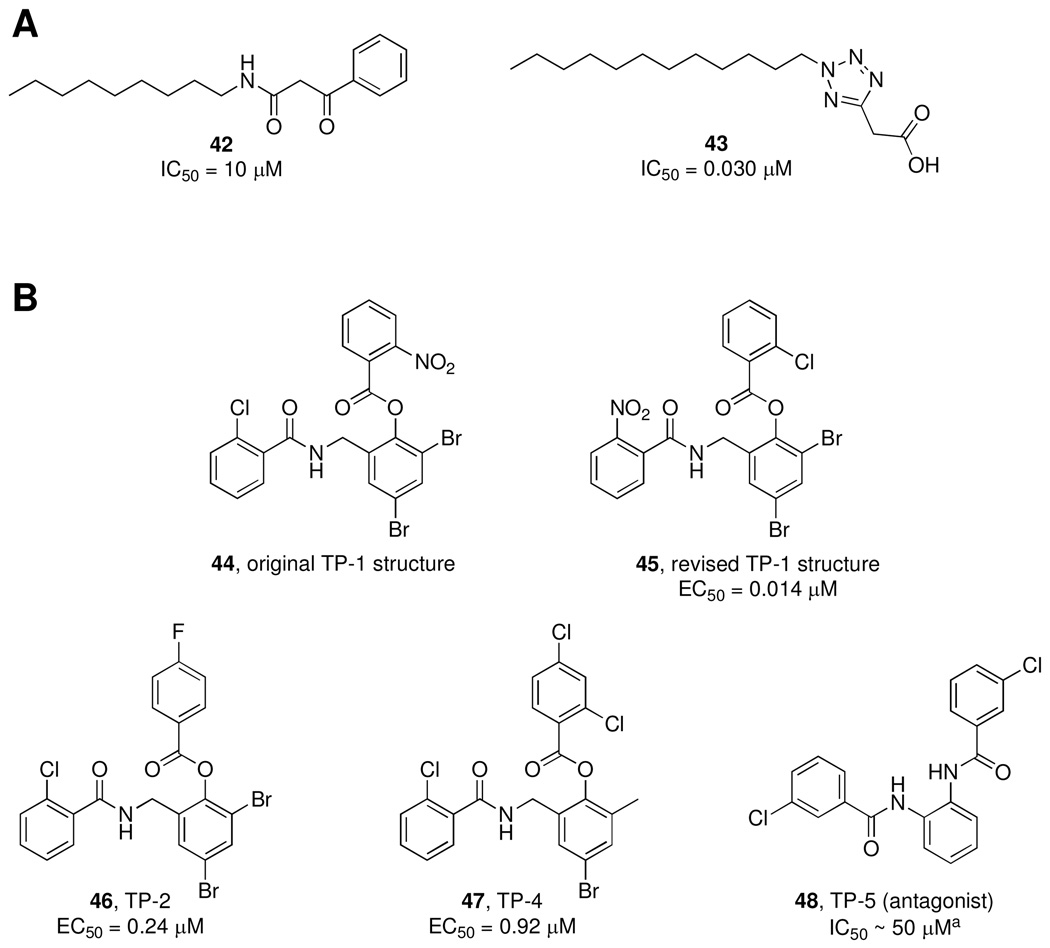

While natural products and focused libraries designed around the natural AHL signal have received the most attention for the development of QS modulators, E. Peter Greenberg and coworkers have developed a cell-based, ultra-high-throughput screening platform to search for inhibitors of LasR-based QS.56 The screening process relies on a strain of P. aeruginosa expressing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) under the control of the LasR-dependent promoter prsaL; thus, agonism or antagonism is detected by increases or decreases in the fluorescent signal. A 200,000 member library was screened and 20 inhibitory compounds were discovered and the two most potent inhibitors, 42 and 43 (Figure 11A), were structurally similar to the native P. aeruginosa signal in that both contain a 12 carbon acyl chain attached to a 5- or 6-member ring.

Figure 11.

A) QS inhibitors identified via high-throughput screening by Müh et al. IC50 values determined using a LasR-dependent yfp P. aeruginosa reporter strain.56 B) Structures of triphenyl compounds. EC50 values represent concentration needed for half-maximal induction of yfp fluorescence. aIC50 value for QS inhibition.

The nature of the ultra-high-throughput screen also allowed for the identification of agonists, and it was this aspect of the assay that allowed for the identification of the first agonist, TP-1 (44), that is structurally unrelated to the natural signal (Figure 11B).57 Interestingly, 44 exhibited excellent specificity for the LasR receptor, and is in fact a stronger activator (EC50 = 0.014 µM) of LasR than 3-oxo-C12-HSL itself (EC50 = 0.140 µM). Indeed, this potent biological activity of 44, along with its enhanced stability to pH and enzymatic degradation relative to 3-oxo-C12-HSL, has rendered the triphenyl scaffold a promising lead for the study of las-dependent QS and the development of novel QS modulators. Inspired by these findings, Greenberg and coworkers also performed a series of in silico docking experiments between triphenyl-derived compounds and the LasR homolog TraR to identify a set of similar compounds and, interestingly, biological evaluation of this new set of analogs revealed both agonists (e.g. 46 and 47) and one antagonist (48). Subsequent docking studies of the active compounds predicted that the generic triphenyl motif is capable of binding at the LasR active site, and unique hydrogen bonding patterns are observed in the models of agonists and antagonists. Even without explicit knowledge of the mechanism of action of the TP compounds, this class of molecules nevertheless represents a potential new class of QS modulators without the pitfalls posed by pH or enzymatic degradation that may plague the lactone-derived analogs.

The interaction between the triphenyl compounds and LasR has been further studied on the molecular level with the recent publication of the crystal structure of LasR in complex with the parent 3-oxo-C12-HSL, 44, 46, and 47.58 Here, the authors demonstrate that productive binding requires that the AHL signal fulfill certain H-bonding requirements and the side chain be of sufficient length and hydrophobicity for proper receptor configuration. Despite significant structural differences, TP agonists 44, 46, and 47 are nevertheless capable of fulfilling these requirements, accounting for the observed activity. A crystal structure of the only inhibitory TP compound, 48, was not obtained due to the instability of the 48-LasR complex. However, docking experiments with 48 and LasR demonstrated that unfavorable steric interactions between one of the chlorine atoms and a nearby leucine residue, thereby disrupting the conformation of LasR. Such a destabilization of LasR by 48 is also reminiscent of the destabilization of the V. fischeri receptor LuxR by the brominated furanone compounds; thus, despite differences in the target proteins and discovery of these two structurally unrelated inhibitors, it may be that they both operate via a similar mechanism of action.

A critical finding arising from the crystallography study was the revised structure of the TP-1 (45) structure from the original publication by Greenberg and coworkers.57 High resolution electron density maps of the crystal structure revealed an electron-rich atom, indicative of the chlorine, at the position originally thought to be occupied by the nitro group (Figure 11B). This revised structure is seemingly more in line with the previous findings by Müh et al, wherein TP-1 is remarkably stable to base.57 However, rigorous characterization of TP-1 (44/45) has not been published to date, nor has the stability of any of these agonists.

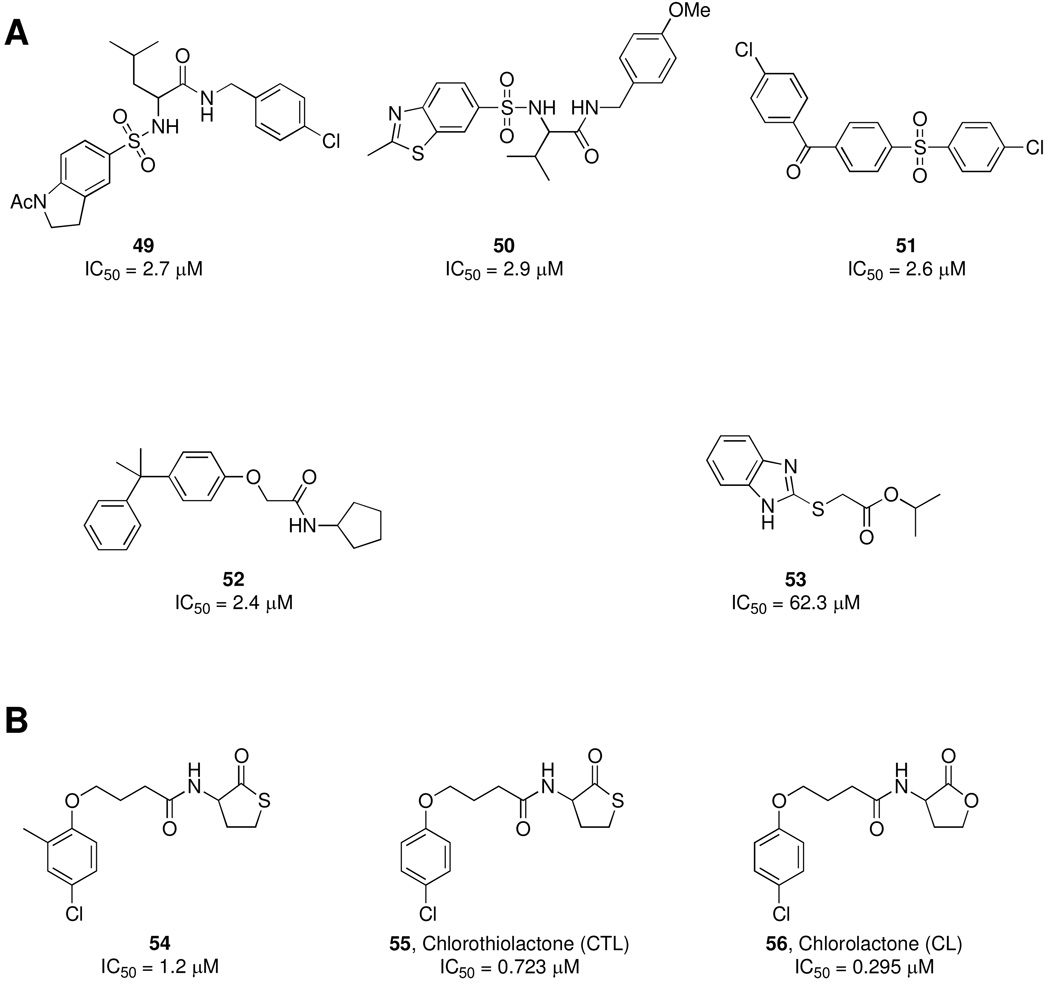

While most of the above work has focused on the investigation of ligand binding and development of antagonists against LuxR-type transcriptional activator proteins, details are sparse concerning the interactions of AHLs with transmembrane LuxN receptors. In many Gram-negative bacteria, the receptor protein LuxR binds intracellular AHL, which then initiates QS through direct interaction with DNA. In the case of the model QS organism V. harveyi, LuxN binds extracellular AHL and initiates a phosphorylation cascade to begin the activation of QS. Towards a better understanding of this phenomenon, Bonnie Bassler and coworkers have recently published a series of studies, the first of which involved the screening of a large library of compounds with the Broad Institute to find a LuxN inhibitor.59 In this screen, 35,000 small molecules were tested for bioluminescence inhibition, and after elimination of compounds found to be toxic or non-specific for AHL-based QS, 15 compounds were identified as potent antagonists of LuxN. Pointing towards the utility of high-throughput screens for the identification of QS modulators, the most potent identified antagonists did not bear structural similarity to the natural 3-OH-C4-HSL signal, (49–53, Figure 12A). These antagonists, in combination with a large panel of LuxN mutants, were also used to decipher the necessary interactions of the LuxN receptor both with the natural signal and the phosphorelay system required for signal transduction.

Figure 12.

A) LuxN inhibitors identified by the screening of a 35,000 member library from the Broad Institute. IC50 values represent concentration needed for 50% reduction of bioluminescence in V. harveyi. B) LuxR inhibitor 54 identified from the panel of LuxN inhibitors and its synthetic derivatives 55 and 56. IC50 values represent concentration needed to inhibit violacein production by 50% in C. violaceum.

With these compounds, the authors also questioned whether similar structures could inhibit both the transmembrane LuxN and cytoplasmic LuxR-type receptors.60 Thus, the same set of 15 compounds was evaluated for the antagonist activity against CviR, the LuxR-type receptor of the human pathogen Chromobacterium violaceum. The authors first examined the activity of their compounds, as well as several AHL analogs with varying acyl tail lengths, in a strain of E. coli that expresses CviR and CviR-dependent gfp. Interestingly, CviR bound intermediate chain AHL analogs (e.g. C8- and C10-HSL) with similar affinities as natural C6-HSL, and, although these complexes still bound the target DNA, transcription of QS genes was inhibited. On the other hand, longer chain AHL analogs (e.g. C12- and C14-HSL) and one potent antagonist (54) were found to interact with CviR but prevent DNA binding of the complex, indicating two distinct modes of action for these QS inhibitors. To further explore the scaffold of lead compound 54, analogs were constructed and chlorolactone 56 (Figure 12B) was found to inhibit CviR-dependent GFP fluorescence in E. coli with an IC50 of 0.377 µM and violacein production in vivo by C. violaceum with an IC50 value of 0.295 µM. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, the authors studied an infection model using C. elegans to demonstrate that both 54 and 56 were able to extend the lifespan of the nematode upon infection with lethal levels of C. violaceum. In doing so, the authors demonstrate that the disruption of bacterial communication does have prophylactic benefits.

The natural QS signals of bacteria, specifically the 3-oxo-C12-HSL molecule of P. aeruginosa, have been shown to exert potent biochemical effects on mammalian host cells. For example, 3-oxo-C12-HSL induces apoptosis in human breast cancer cells,61 as well as in macrophages and neutrophils,62 and, in research stemming from our laboratory and others, modulates transcriptional activity of NF-κB, the central regulator of gene expression in the innate immune system during infection and inflammation.63–66 Furthermore, 3-oxo-C12-HSL has exhibited inhibition of proliferation and cytokine secretion in human leucocytes, an aspect of AHLs that has been further investigated by capitalizing on the 3-oxo-C12-HSL scaffold as a lead for the development of analogs to enhance the immunosuppressive activity, with the potential for new treatments of autoimmune diseases.67

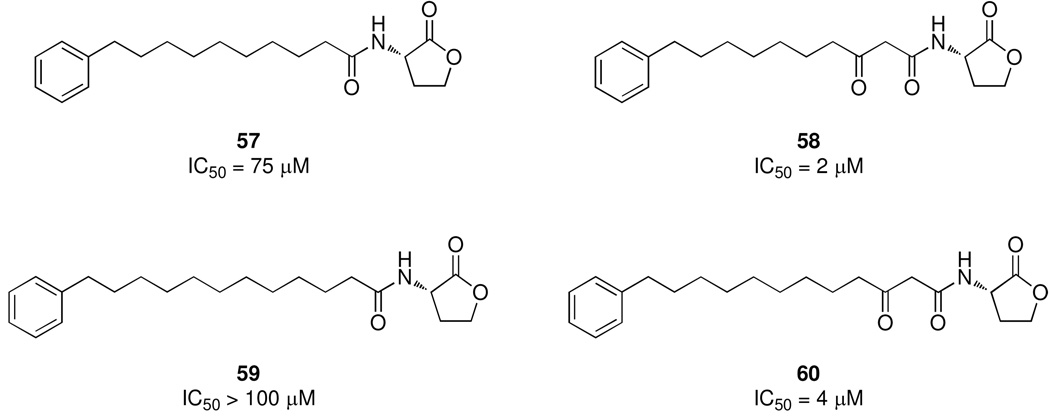

Analogs of 3-oxo-C12-HSL have also been examined for activity against cancer cells; however, in light of the potential negative effects of P. aeruginosa QS on cancer patients, the analogs were designed to minimize QS activity and optimize anti-cancer activity.68 In this study, a series of phenylacylhomoserine lactone analogs were constructed by microwave-assisted synthesis, and assayed for both activity against cancer cell growth and lack of agonism towards P. aeruginosa QS. The 3-oxo functionality was required for inhibition of cancer cell growth, but many analogs, including 58, also exhibited excellent QS activation (Figure 13). One promising lead was identified (60), which incidentally shares the structural feature of the C12 acyl chain with the natural 3-oxo-C12-HSL signal, suggesting therapeutic avenues for the development of QS analogs outside the realm of antimicrobial intervention. Thus, in summary, research towards the modulation of bacterial communication may not only provide new vistas into the control of bacterial infection, but may also signal new directions in the development of agents against other human diseases and conditions.

Figure 13.

Analogs of 3-oxo-C12-HSL with activity against cancer cell growth. IC50 values represent concentration required to inhibit PC3 growth by 50%.

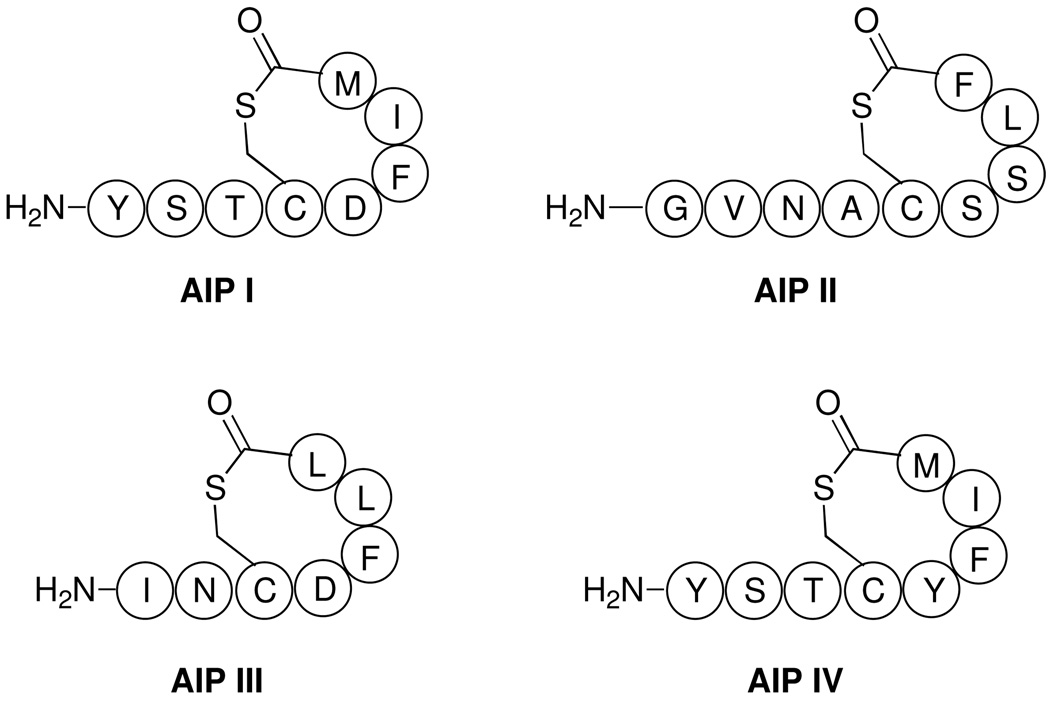

AIPs

Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae, in contrast to the small molecule signals of Gram-negative bacteria, use linear or post-translationally modified peptides as their autoinducing signals.69 Specifically, the human pathogens S. aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis utilize cyclic peptides, referred to as autoinducing peptides (AIPs).70–72 Most of the work concerning the development of QS modulators in Gram-positive bacteria has focused on the AIP systems of Staphylococci, specifically S. aureus, and as such will be the focus of this section. These oligopeptides are secreted into the environment by transport proteins and detected by a receptor histidine kinase (HK).72,73 As part of a classical two-component system, the HK receptor is coupled to a response regulator (RR) protein, and upon ligand binding, activates the RR protein to induce expression of the target genes. This system plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of S. aureus, as the expression of a number of genes encoding virulence factors is regulated by a QS-dependent global regulatory locus known as accessory gene regulator (agr).74 The agrsystem contributes to pathogenesis by orchestrating the temporal, cell density-dependent expression of virulence genes encoding cell surface proteins, such as protein A, coagulase, and fibronectin-binding proteins, as well as secreted proteins including proteases, hemolysins, toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1), and enterotoxin B.75,76 It is important to note that, in contrast to most other bacterial QS systems, in staphylococci, biofilm formation is inversely controlled by QS, i.e. inhibition of QS signaling enhances the formation of biofilm; a fact which might make the development of prophylactic or therapeutic QS antagonists particularly challenging.77,78

The agr operon is composed of four genes, agrA–D, which encode the complete AIP-dependent QS signaling circuit.72 The AIP, which is synthesized as a 50 amino acid (AgrD) propeptide that is processed by the membrane bound protein AgrB, and subsequently secreted. The extracellular AIP binds to its cognate AgrC transmembrane receptor causing autophosphorylation of AgrC, which in turn phosphorylates AgrA to activate promoters P2 and P3. The P2 promoter initiates transcription of the agr operon, resulting in increased synthesis of the AIP, while the P3 promoter is responsible for the up-regulation of a large number of virulence factors.73

The AIPs are composed of seven to nine amino acids, including a highly conserved cysteine residue, which forms a thioester linkage with the C-terminal carboxyl group to generate the cyclic peptide (Figure 14).69 The cyclic structure of the peptide is required for binding to its cognate AgrC receptor, while the other half of the AIP is known as the “tail” and is a linear sequence of 2 to 4 amino acids.79 The tail sequence is important for activation of the AgrC receptor.79 All S. aureus strains can be classified into 4 different agr groups, labeled I–IV, producing four different AIPs that bind to their respective AgrC receptors.80 Interestingly, no crossactivation is observed between AIPs and AgrC receptors of different agr groups, but rather the binding of an AIP to a non-native AgrC receptor results in inhibition of agr functions.73,80,81 The significance of this phenomenon in vivo has yet to be delineated, but in spite of this uncertainty, the crossinhibition of AIPs has provided a mechanism for the study of QS inhibition in S. aureus both in vivo and in vitro, as well as a roadmap for the development of novel AIP signaling antagonists.73

Figure 14.

Structures of the AIP signals used by S. aureus.

The validity of the agr system as a target for therapeutic intervention has been established, in part, by the observation that S. aureus agr mutants are attenuated for virulence.82 Additionally, the cross-group inhibition of the AIPs was exploited to demonstrate that a QS inhibitor is indeed capable of modulating S. aureus pathogenesis in animal models.83 In this study, a solid phase synthetic route was used to establish the structures of AIP I and II. Subsequently, mice were infected with group I S. aureus and concurrently treated with AIP-II. The resulting inhibition of the agr system caused diminished abscess formation by group I S. aureus, a finding that served to establish the therapeutic potential of QS inhibition and confirm the role of QS as an indispensable process in S. aureus infections. Notably, synthetic efforts by our laboratory towards the AIP signals have also enabled the generation of AIP analogs to be used as haptens for the generation of anti-AIP antibodies. In particular, an anti-AIP-IV antibody suppressed abscess formation in a murine model and protected mice from a lethal S. aureus challenge.84

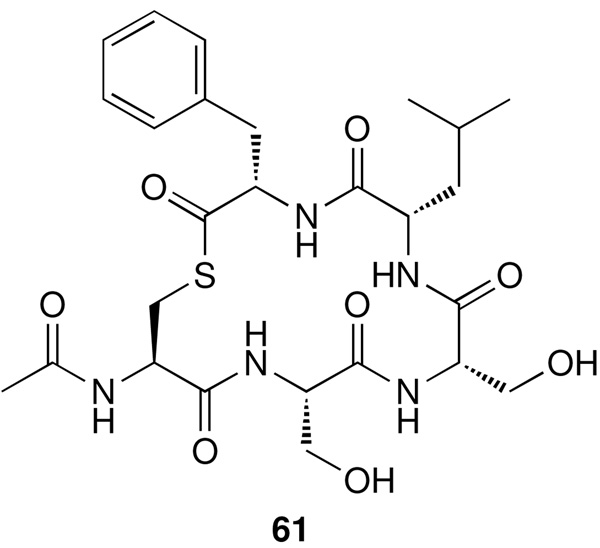

The groups of Tom Muir and Richard Novick have jointly carried out numerous structure activity studies of the AIPs with their corresponding AgrC receptor, and have shed light on important structural features required for both agonist and antagonist activity.79,80 This work led to the development of a global inhibitor (61) of the S. aureus agr locus in all four groups (Figure 15 and Table 2).80 Global inhibitor 61 is composed of the AIPII macrocycle without the linear amino acid tail region. Interestingly, 61 contains the thioester linkage, which was found to be important for antagonism of group II AgrC (self inhibition), while the lactam or lactone linkage retained inhibitor activity for the other AgrC groups.

Figure 15.

Structure of global inhibitor 61.

Table 2.

Inhibition of the agr response by global inhibitor 61

| Group I | Group II | Group III | Group IV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (µM) | 0.272 | 0.209 | 0.010a | 0.188 |

Experiment was based on HPLC analysis of δ toxin. All other results were based on β-lactamase reporter assay.

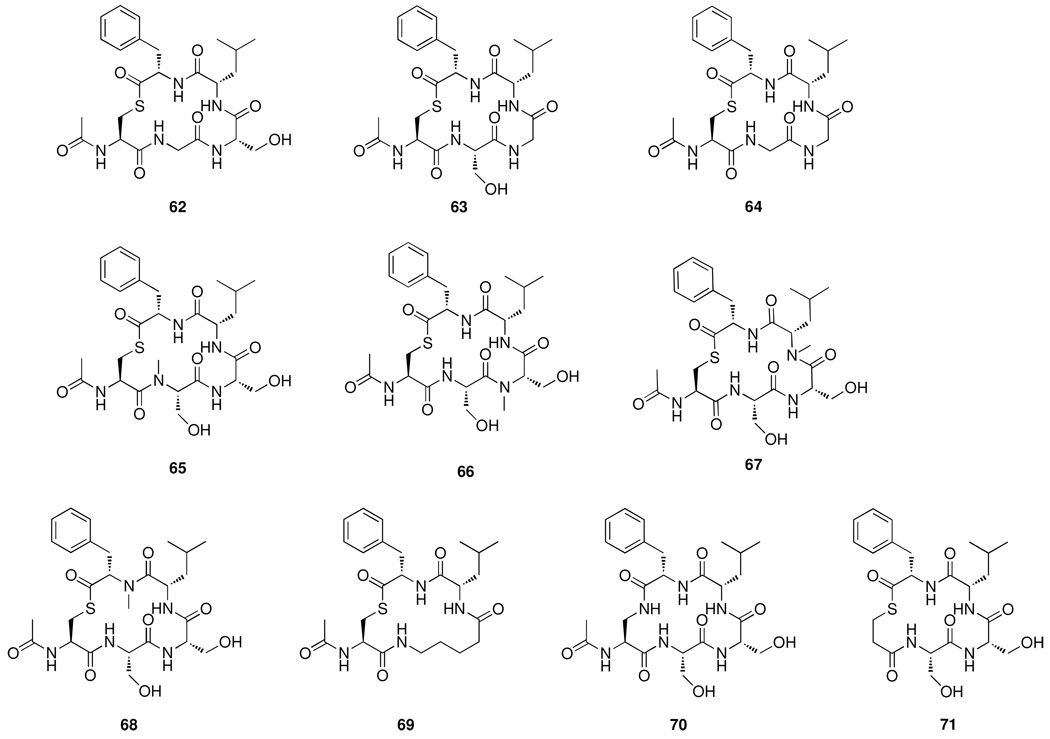

Furthering the initial development of a global inhibitor, derivatives of the AIPII macrocycle were produced and evaluated for antagonism of the AgrC receptor.85 Various alterations where made to the parent compound to explore important structural features important for activity: replacement of serine with glycine (62–64), N-methylation of the amides (65–68), substitution of the adjacent serines with a methylene linker (69), replacement of the thioester with a lactam (70) and removal of the cysteine acylated amino group (71, Figure 16).

Figure 16.

SAR study of AIP-II

The analogs were tested in a cell-based reporter assay for inhibition of the AgrC receptor of groups I and II reporter strains (Table 3). Interestingly, all the analogs are more potent antagonists to the group I AgrC receptor than the group II AgrC receptor. It has been shown that the AIP analogs are not potent antagonists for their parent AgrC receptor.79,86,87 Replacement of the serine residues with a glycine residue gave mixed results. Substitution of the serine closest to the N-terminal (61) resulted in an increased IC50 for group I and a drastic IC50 increase for the group II AgrC receptor. However, replacement of the serine residue closest to the C-terminal (62) resulted in a decrease in the IC50 value by 2-fold for both I and II group AgrC receptors. The substitution of both serine residues with glycine resulted in a small decrease of the IC50 values for both AgrC groups. N-methylation of the amides in the macrocycle (64, 65) showed a large increase in the IC50 and, in the case of leucine or phenylalanine, NH methylation (66, 67) abolished activity. Inhibition of both groups I and II AgrC receptors was also drastically decreased by substitution of the two adjacent serine residues with a propyl linker (68) and replacement of the thioester bond with an amide (69). Finally, removal of the amino group of the cysteine (70) again resulted in an increase in the IC50. In this SAR study of the macrocycle region of AIP-II the authors demonstrated a strict requirement of amino acid sequence for tight binding to the AgrC groups I and II receptors. However, macrocycle 62 was identified as a good inhibitor of the AgrC of groups I and II, albeit with 5-fold decreased activity in group II. Thus, an inhibitor was identified from the SAR study, and the authors were able to conclude that thiolactone linkage, along with the phenylalanine and leucine residues, were the only residues essential for antagonism of both the AgrC I and parent AgrC II receptors. However, additional functionalities are required for antagonism of the parent AgrC receptor, a finding that may be rationalized by the fact that the AIPII signal itself is already capable of inhibition of AIPI receptors, whereas the AIPII signal must undergo significant modification so that it is not recognized as an agonist by its cognate receptor.

Table 3.

IC50 values for inhibition of the AgrC receptor of groups I and II. All values reported in µM.

| Analog | Group I | Group II |

|---|---|---|

| 62 | 0.189 | 1.160 |

| 63 | 0.040 | 0.194 |

| 64 | 0.077 | 0.238 |

| 65 | 0.639 | 7.880 |

| 66 | 0.319 | 1.050 |

| 67 | No Inhibition | No Inhibition |

| 68 | No Inhibition | No Inhibition |

| 69 | 1.141 | 507 |

| 70 | 1.390 | 167 |

| 71 | 1.680 | 47.3 |

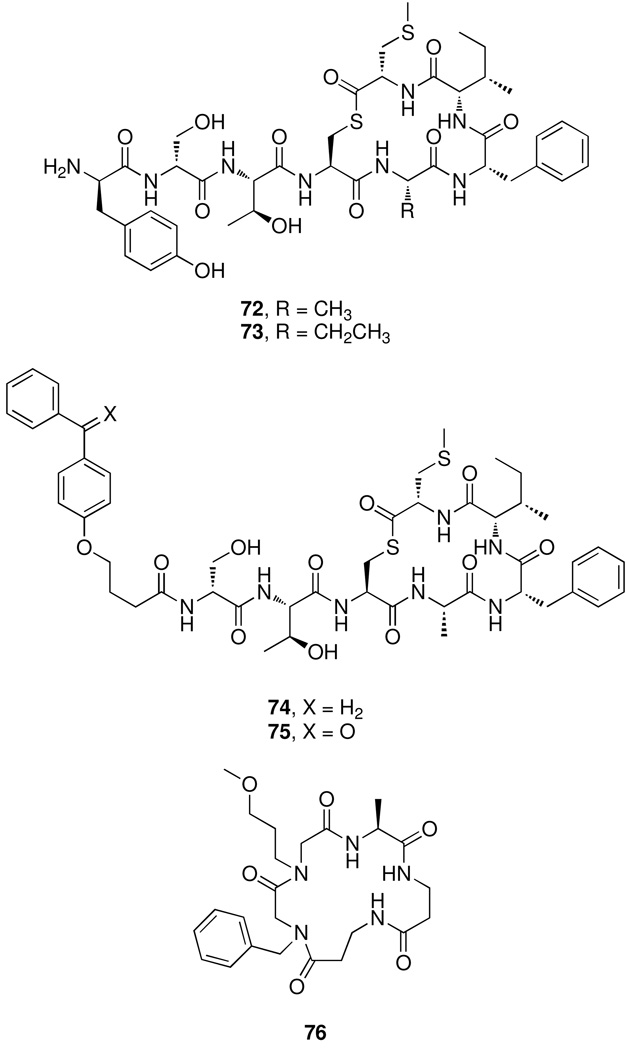

In another study, Weng Chan and coworkers focused on the AIPI for development as an inhibitor of group I and II AgrC receptors.88 Previously, the laboratory of Paul Williams identified a potent inhibitor (72) of the AgrC receptor of group I by replacing an aspartic acid of AIP-I with an alanine residue.76 In a later study, 72 was demonstrated to be an even more potent inhibitor of the AgrC receptor of group II (group I IC50 = 21 nM; group II IC50 = 4 nM).88 They sought to enhance this analog by replacing the methyl group of the alanine side chain with an ethyl group (73) to increase the hydrophobic nature of that position (Figure 17). This subtle change from a methyl to an ethyl group produced an analog more potent than the parent molecule in regards to the inhibition of the AgrC of group II (2.8 nM). However, 73 was not as potent an antagonist against the AgrC group I, resulting in a 6-fold increase in IC50 from the parent analog (72). Along with this subtle alteration they also replaced the tyrosine residue at the N-terminus with 4-benzoylphenoxybuytric acid (74, 75) to create an access point for chemical derivatization and the incorporation of the benzophenone photophore to probe the binding locations of the AIPs to the AgrC receptors. This alteration at the N-terminus of the tail region resulted in decreased potencies for the AgrC receptors of groups I and II, but nevertheless 74 and 75 are capable of binding to the AgrC receptors and could be further developed for photolinking experiments. Although Chan and coworkers were able to produce a potent inhibitor of the AgrC receptor of group II, this work reinforces the observations that antagonists derived from an AIP have excellent cross-inhibitory activity and only modest in-group activity, demonstrating potential limitations of AIP analogs as broad-spectrum inhibitors.

Figure 17.

Structures of AIP analogs.

Several reports by Naomi Balaban and coworkers have described another potential avenue for the inhibition of S. aureus QS, which lies in the prevention of agr activation via the TRAP (targeting of RNAIII-activating peptide) pathway. TRAP has been suggested to be activated by the autoinducing RNAIII activating protein (RAP), which in turn controls the activation of agr. An inhibitor of this system, discovered by Balaban and coworkers, is a naturally-occurring seven amino acid peptide, coined RNAIII inhibiting peptide (RIP), with the sequence YSPWTNF-NH2.89,90 This peptide was suggested to inhibit QS of S. aureus by competing with RAP for activation of TRAP and ultimately inhibit agr QS. Indeed, RIP has been shown to inhibit toxin production and even mitigate wound infections by S. aureus.90,91 However, RIP also prevented biofilm formation, which usually does not indicate agr QS antagonism in S. aureus.92,93 Thus, the validity of RIP as a bona fide QS inhibitor has been questioned. Recently, a series of reports demonstrated that mutations in the gene encoding TRAP do not result in altered agr activation,94 biofilm formation,95 and overall in vivo virulence.96 While RIP may still represent a viable lead for the discovery of both virulence and biofilm formation inhibitors of S. aureus, its mechanism of action has not been unequivocally delineated but likely does not involve specific agr QS quenching. Interestingly, the pharmacophore of RIP was determined by Balaban and colleagues using in silico techniques, screened against a library of commercially available small molecules, and a non-peptidic RIP analog, namely hamamelitannin, with similar biological activity was discovered.97

Most of the work described in this section thus far has focused on cyclic peptide analogs of natural AIPs, but another class of molecules that could be developed into antagonists of the AgrC receptor is peptoids. Peptoids are oligomers composed of N-substituted glycine units and have exhibited high biostability and can be easily synthesized by combinatorial approaches to produce large compound libraries.98,99 Indeed, peptoids are currently being investigated for biological activity in a number of areas including antimicrobial properties.100 In one study, a series of peptoid-peptide hybrids, or peptomers, derived from the AIP-I signal were synthesized, and one of the peptomers (76) was shown to stimulate biofilm formation in S. aureus (Figure 17).101 As mentioned above, it had previously been shown that inhibition of the AIP QS signaling resulted in increased biofilm formation,78 leading to the hypothesis that 76 was an antagonist of the AgrC receptor of group I S. aureus. They were able to show that the peptomer was biologically active, but a direct comparison of this peptoid with other known AIP antagonists is difficult, as the antagonist activity of 76 was deduced from the formation of biofilm, rather than a direct inhibition of the AIP-regulated QS system. However, the peptoid scaffold does show promise as an inhibitor of the AgrC receptor and may provide a new avenue for the development of novel analogs.

AI-2 and DPD

In addition to the two QS systems described above that are exclusive to either Gram–negative or –positive bacteria, AI-2 QS systems have been proposed to exist in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains, and indeed, the synthase for the AI-2 precursor 4,5-dihydroxy-2,3-pentanedione (DPD), luxS, is present in a wide variety of bacteria.102 AI-2 has also been found to regulate an array of microbial processes, including bioluminescence in Vibrio harveyi,102 AI-2 uptake and destruction in Salmonella typhimurium and Sinorhizobium meliloti,103,104 virulence factor production in Vibrio cholerae and Vibrio vulnificus,105,106 and the formation of mixed biofilms by Streptococcus oralis and Actinomyces naeslundii.107

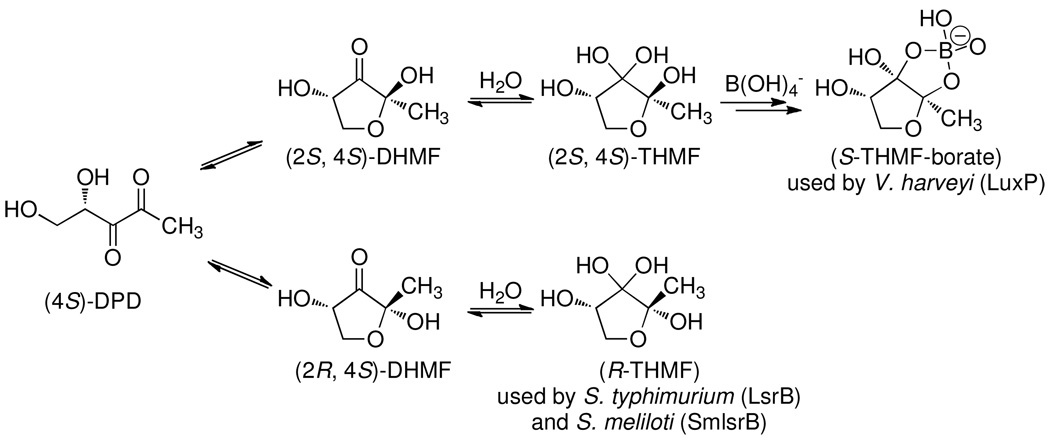

The first structure of AI-2 was solved, using x-ray crystallography, in complex with the V. harveyi receptor protein LuxP.108 In this crystal structure, AI-2 was found to exist as a furanosyl borate diester (S-THMF-borate, Figure 18), likely arising from the complexation of boronic acid by the cyclized form of DPD. Although initially puzzling, this finding was later rationalized by the high concentrations of boric acid in marine environments (0.4 mM) inhabited by V. harveyi. Subsequent studies revealed that the enteric bacterium S. typhimurium responds to the furanosyl form of R-DPD without boron ((2R,4S)-2-methyl-2,3,3,4-tetrahydroxytetrahydrofuran, R-THMF), leading to the redefinition of AI-2 autoinducers as a group of signals derived from DPD.109 Recently, the third crystal structure of an AI-2 binding protein was solved, this time of the SmlsrB (LsrB of Sinorhizobium meliloti) protein found in the plant symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti, in complex with the R-THMF form of DPD.104 These findings support the hypothesis of AI-2 as an interspecies signal in that the three identified AI-2 structures are formed from DPD, implying that DPD released by one species may be detected and recognized by several different species as various isomers. Interestingly, S. typhimurium and S. meliloti respond to the 2R isomer, whereas V. harveyi recognizes a borate diester form of AI-2 derived from the 2S isomer (Figure 18). As such, the reactivity, variable stereochemistry, and capacity for metal chelation of cyclic DPD highlights its potential for interspecies signaling and argues that modified DPD-based signals may be recognized in the extremely diverse environments inhabited by bacteria. The discovery of the AI-2 system in S. meliloti is particularly intriguing, as this soil-dwelling bacterium does not produce its own DPD. This has led to the hypothesis that the AI-2 response system of S. meliloti may allow for the survey of the bacterium’s surroundings and also to interfere with the communication of its competitors via internalization of AI-2 signals.104

Figure 18.

Equilibrium of the two known AI-2 signals.

Since the initial discovery of luxS,110 it has been correlated to a variety of phenotypes, including bioluminescence, expression of virulence factors, and biofilm formation. However, the discovery of a large proportion of AI-2 regulated processes has relied on the creation of luxS mutants; this technique has been the target of criticism, as LuxS plays an important role in the removal of toxic intermediates from the activated methyl cycle.111 As such, the observed phenotypes of luxS mutants may either be a result of the loss of communication or the changes in metabolic fitness. In spite of this criticism, several reports have provided evidence in support of AI-2 as an interspecies signal.104,107,112,113

An interspecies and interkingdom signaling system, defined by the bacterial receptor protein QseC, has been reported. The QseC receptor recognizes the uncharacterized bacterially-derived signal AI-3, as well as adrenergic signals produced by mammalian hosts, to regulate the production of virulence factors in a variety of bacteria.114,115 This system was first characterized in enterohemorrhagic E. coli, but homologs of QseC are present in a variety of pathogenic bacteria, including Salmonella sp., Haemophilus influenzae, and Shigella spp.114 Mutation of luxS was initially found to effect the production of AI-3 as well as AI-2,116 but subsequent studies have demonstrated that the LuxS enzyme is not directly responsible for AI-3 synthesis.117 The therapeutic utility of disrupting interspecies and interkingdom communication was established with the discovery of a compound that specifically inhibits QseC regulated signaling without toxicity towards the bacteria, and consequently prevents lesion formation on cultured epithelial cells by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli and protects mice from death by Francisella tularensis and Salmonella typhimurium infections.118

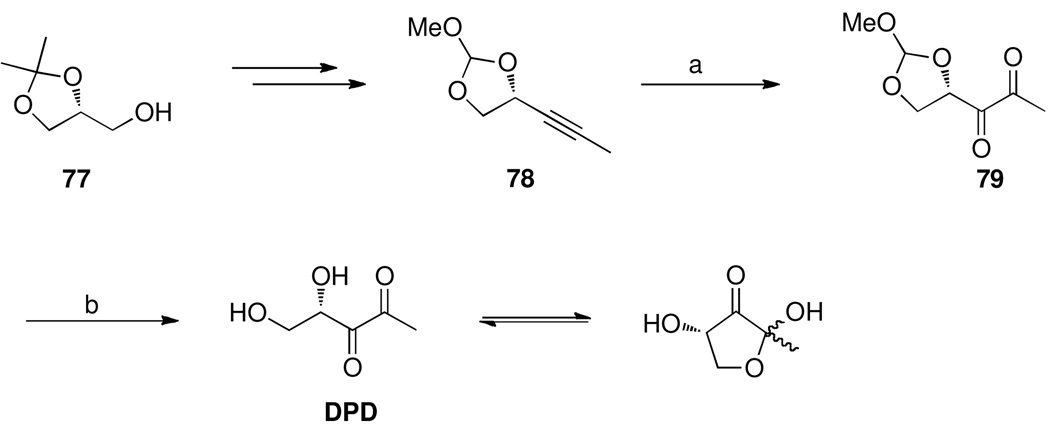

Chemical confirmation of DPD as the core signaling molecule of AI-2-based QS was provided through chemical synthesis and biological evaluation of DPD by our laboratory (Scheme 3).119 In spite of the small size of the DPD molecule, it presented a synthetic challenge because of its highly oxygenated carbon framework as well as its reactivity and propensity for polymerization. Synthetic efforts were further hampered by harsh oxidation conditions to generate the diketone moiety as well as the lability and volatility introduced by the methoxy methylene acetal protecting group (79). An alternative synthesis was later reported by Martin Semmelhack an coworkers for multi-gram quantities (Scheme 4A),120 while an additional synthetic route was published using O3-mediated oxidative cleavage to form the diketone (Scheme 4B).121

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of DPD as described by Meijler et al.119

Reagents: (a) KMnO4, acetone, aq. buffer, rt, 20 min. (b) H2O, pH 6.5 (K2HPO4/KH2PO4 (0.1 M), NaCl (0.15 M)), 24 h

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of DPD described by A) Semmelhack et al.120 and B) De Keersmaecker et al. 121

Reagents: (a) KHCO3, KIO4, H2O/CH2Cl2, rt, 18 h; (b) RuO2, NaIO4, MeCN, CCl4, H2O, rt, 15 min.; (c) H2SO4, 2 h; (d) O3, MeOH, Me2S, 24 h.

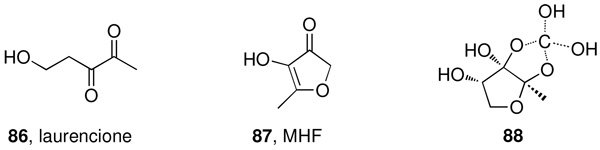

The establishment of DPD as the core signaling molecule of AI-2 based QS provided an opportunity for the development of both structure-based and computationally designed agonists and antagonists. As a first step, several studies sought to establish the role of boron in the AI-2 signal. With an established route to synthetically pure DPD, 1H NMR was used to monitor the spontaneous complexation of boron to DPD and the DPD analog laurencione.120 The natural products laurencione and 4-hydroxy-5-methyl-3-(2H)-furanone (MHF) were also shown to form a boron complex, but both of these analogs exhibit lower activity than DPD.122,123 Additionally, during efforts to evaluate the potential for different metal species to serve as a boron mimic, McKenzie et al deduced that the putative carbonate analog, 88, of the borate diester AI-2 species effectively mimics the biological activity of borate-DPD (Figure 19).124

Figure 19.

Structures of laurencione, MHF, and the putative carbonate-DPD species.

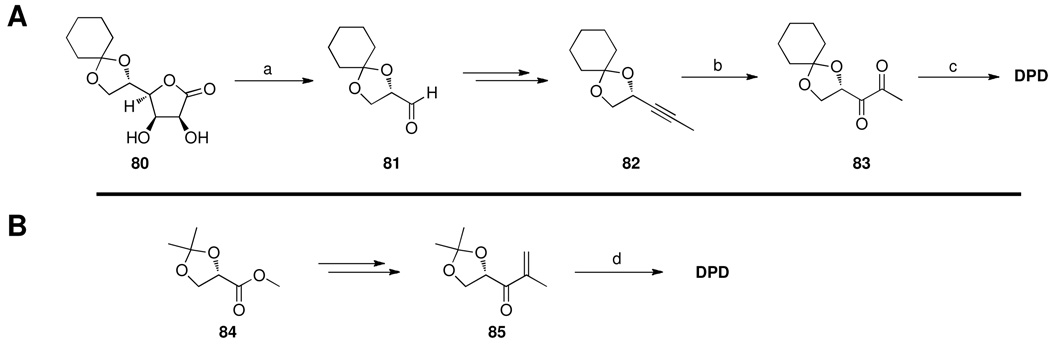

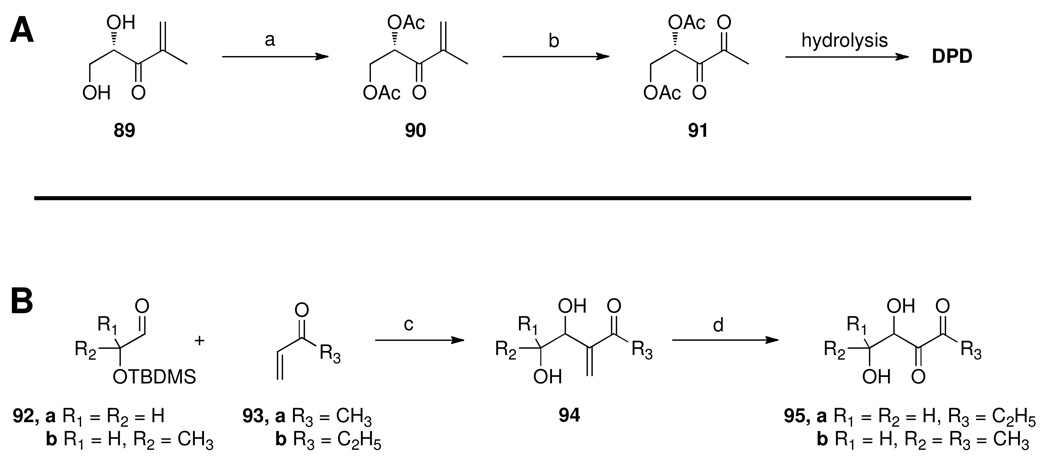

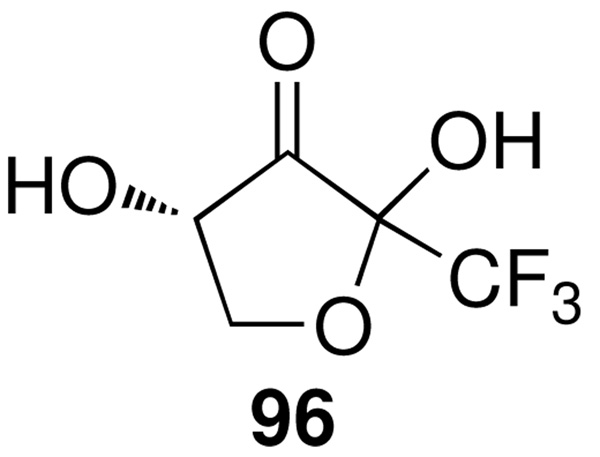

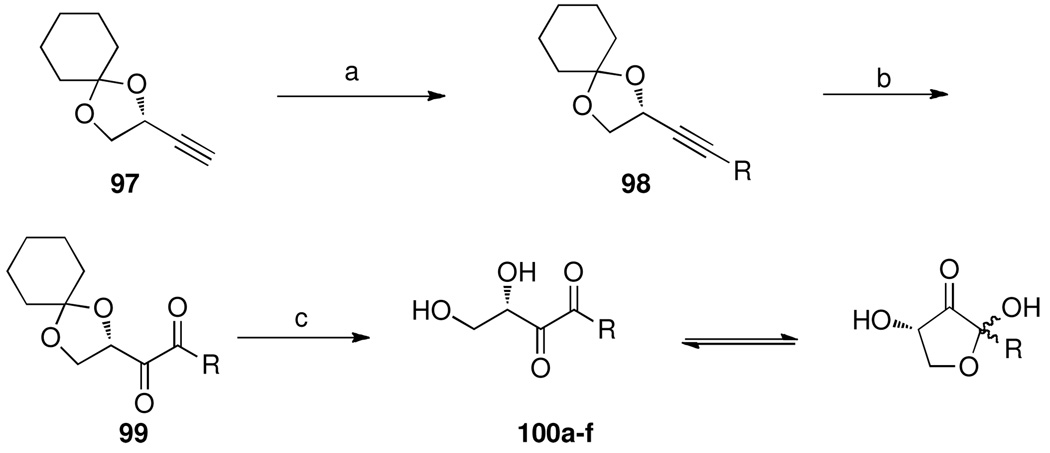

Due to the instability of DPD at high concentrations and the relatively compact framework, the DPD molecule itself presented a challenge for organic chemists. As such, many studies, both initial and current, focused on the synthesis of one or two simple analogs. This is exemplified in a report from the research group of Alain Doutheau, in which bis-acetyl DPD was constructed using the Baylis-Hillman/ozonolysis methodology developed by the same laboratory (Scheme 5A).125,126 Because the final product of the previous syntheses of DPD is always a dilute aqueous solution, it was reasoned that protection of the diol as the bis-acetate 91 would allow for the isolation of this pure DPD precursor, which would then be cleaved in vivo to reveal the active signal. This was indeed the case, as 91 displayed equal activity to DPD itself.125 This same synthetic route was also used for the construction of C5-alkylated and 5-O-acylated derivatives 95, although only the racemic compounds were obtained (Scheme 5B).126 Another compound, the trifluoromethyl analog 96 (Figure 20), was reported as a chiral form using the camphor-derived Oppolzer’s sultam reagent in Baylis-Hillman reaction, and the compound demonstrated the most potent agonistic activity observed to date, although it was less active than DPD in the V. harveyi bioluminescence assay (EC50 = 30 µM vs. EC50 = 3 µM for DPD).127 The expected rationale for this observed activity was that the electron withdrawing effects of the trifluoromethyl group would render the adjacent carbonyl more electrophilic and promote formation of the active cyclic species; however, modeling studies of this compound revealed that the trifluoromethyl group also caused the two adjacent oxygen atoms (in the hydrated form) to be less available to form the requisite H-bonds with the LuxP receptor, possibly accounting for the diminished activity relative to DPD.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of A) Ac2-DPD 91 and B) C5-alkyl DPD analogs 95.

Reagents: (a) Ac2O, pyr., Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 18 h; (b) O3, MeOH, Me2S, −78 °C to rt, 24 h; (c) i) THF, DABCO, 0 °C; ii) TBAF, THF, rt. (d) O3, MeOH, Me2S, −78 °C to rt.

Figure 20.

Structure of trifluoro-DPD.

As a first step towards the discovery of new modulators of AI-2 based QS, our laboratory created a panel of alkyl-DPD analogs to systemically probe the effects of the substitution pattern at C1 (Scheme 6).128 The synthesis is founded upon previously reported routes for the construction of DPD, but modified for the introduction of alkyl groups at the C1 position (100).119,120 Modulation of bioluminescence was examined using V. harveyi MM32, a cell line incapable of producing luminescence either through the AHL pathway or AI-2 pathways in the absence of exogenous DPD.119,120,129 When the analogs (25 µM) were incubated with V. harveyi and 1 µM DPD to monitor antagonism, a synergistic effect was observed. Interestingly, these compounds were inactive in the absence of DPD, leading to the hypothesis that these analogs are interacting with the AI-2 receptor LuxP in a manner productive only in the presence of natural DPD, possibly via interaction with an allosteric binding site and increased hydrophobic interactions.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of C1-alkyl DPD analogs.

Reagents: (a) n-BuLi, R-I, −78 °C to rt, 12 h; (b) RuO2, NaIO4, MeCN, CCl4, H2O, 15 min.; (c) pH 1.5, 6 h.

The panel of C1-substituted alkyl-DPD analogs was also evaluated for (ant)agonist activity in S. typhimurium, as measured by a β-galactosidase transcription assay.121 Assays were conducted using a ΔluxS strain with a lacZ-lsr fusion, and assays were performed in the presence of DPD (antagonist assay) or in the absence (agonist assay) of DPD. No agonists were identified from the screening, but in the presence of 50 µM DPD, all compounds acted as antagonists of AI-2 based QS. Notably, the propyl- and butyl-substituted analogs were found to be potent inhibitors with IC50 values 10-fold less than the concentration of the natural DPD signal (Table 4). These analogs possessed two interesting and unique properties; first, they had strikingly different biological effects in the two different species V. harveyi and S. typhimurium. Secondly, the difference of the length of the alkyl chain brought a dramatic change to the biological activity ranging from the natural substrate to no activity to a potent inhibitor. Interestingly, these alkyl-DPD analogs were also found to inhibit the bioluminescence of V. harveyi when added to cultures that had already initiated QS. 50 This finding may speak to the difference in QS signal transduction between low and high cell density cultures of V. harveyi or potential differences in activity of QS modulators under different assay conditions.

Table 4.

Activity of alkyl-DPD analogs against the QS of S. typhimurium. All values reported in µM.

| Compound | R | IC50 in S. typhimuriuma |

|---|---|---|

| 100a, ethyl-DPD | CH2CH3 | > 50 |

| 100b, propyl-DPD | CH2CH2CH3 | 5.30 |

| 100c, butyl-DPD | CH2(CH2)2CH3 | 5.04 |

| 100d, hexyl-DPD | CH2(CH2)4CH3 | 24.9 |

| 100e, phenyl-DPD | CH2CH2(C6H5) | > 50 |

| 100f, azidobutyl-DPD | CH2(CH2)3N3 | 20.3 |

Assay performed in the presence of 50 µM DPD.

A later report from Meijler and coworkers observed a similar trend of synergistic agonist effects between the alkyl-DPD analogs and the natural DPD signal, with a decrease in activity correlating to increasing alkyl chain length.130 Another study, this time by the laboratory of Herman Sintim, observed the same synergistic activity between alkylated DPD analogs, although in this study there was not a clear trend between size and shape of the alkyl groups and the observed synergistic activity, thus suggesting a promiscuous mechanism of signal recognition.131 The alkyl-DPD analogs of the former study were also shown to have an effect on the QS of P. aeruginosa. Although P. aeruginosa does not possess a known LuxS enzyme, it has been shown to respond to the AI-2 signal to regulate pathogenicity.132 Thus, the alkyl-DPD analogs inhibited lasI-dependent luminescence in a modified PAO1 reporter strain and pyocyanin production in wild type P. aeruginosa.130 Although the mechanism of QS inhibition in P. aeruginosa was not determined, the authors hypothesize that the alkyl-DPD analogs act on the las-regulated system, as these analogs bear structural resemblance to known inhibitors of LasR (e.g. 2, Figure 2), including the brominated furanones (36–39, Figure 9).39

As described in the AHL section, the halogenated furanone natural products have shown excellent activity against both AHL and AI-2 dependent QS systems. In particular, the natural product (5Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone 36 possesses excellent inhibitory activity against the AI-2-regulated bioluminescence system of V. harveyi. The activity of this compound against AI-2 based QS was assessed using a double mutant of V. harveyi that lacks the receptors for the AHL and CAI-1 signals, thus the only luminescence produced must be a result of the AI-2 system. Both the natural product 36 and the synthetic furanone 41 (Figure 9) were shown to inhibit bioluminescence in this strain, with no effects on cell growth. Willy Verstraete and coworkers have shown that treatment with either the natural 36 or synthetic furanone 41 imparts protection of the shrimp Artemia nauplii from lethal infections of V. harveyi and V. campbellii.133 However, the furanones become toxic at concentrations slightly higher than those needed to significantly increase survival of the shrimp, possibly limiting the utility of these compounds in vivo. Nevertheless, these data suggest a possibility for therapeutic intervention via AI-2 QS inhibition in animals. Furthermore, treatment of bacterial infection in aquaculture has seen heavy dependence on the use of antibiotics, and, consequently, the rise of antibiotic resistance; as such, it is for this same reason that QS represents an attractive target in the treatment of human disease.

In addition to the effects on Vibrio sp. and P. aeruginosa, the brominated furanones have exhibited QS inhibitory activity against a variety of bacteria, including both Gram–positive and –negative strains. Notably, the brominated furanones inhibit the swarming behavior, biofilm formation, and percentage of live cells in biofilms of E. coli. However, colony growth on agar plates revealed no cytotoxicity of the furanone against E. coli, indicating specific QS inhibition.134 A subsequent study by Wood and coworkers employed DNA microarrays to show that the furanone inhibited 80% of the same genes that were activated by AI-2.135,136 Additionally, therapeutic and industrial applications may be found for the brominated furanone compounds outside of specific QS inhibition, as they have exhibited activity against biofilm formation by S. typhimurium,137 virulence gene expression of Bacillus anthracis,138 swarming and biofilm formation of Bacillus subtilis,139 and steel corrosion caused by Desulfotomaculum orientis.140 Thus, the brominated furanones have therapeutic and industrial value beyond that of specific QS inhibition, although it should be noted that the brominated furanones also significantly inhibit bacterial growth in many of the above-mentioned examples, raising concerns about the specificity of the QS antagonism.

Two possible mechanisms of action have been reported for the QS inhibition of the brominated furanones: interaction with the LuxRVh regulatory protein (vide supra) and covalent modification of the DPD synthase LuxS.48 A recent report by Zhaohui Zhou and coworkers details the inhibition of the LuxS enzyme by the brominated furanones, which the authors propose occurs via two possible mechanisms both of which occur through conjugate addition by a nucleophilic residue in the active site of LuxS.48 In support of this, the enzyme-inhibitor complex was subjected to mass spectrometry, and a LuxS adduct was found that corresponds to the addition of one furanone molecule and loss of a bromine atom. Furthermore, using protein digestion and MS analysis, binding of the furanone was found to occur at a cysteine residue in the active site, whereas other more accessible and reactive cysteine residues were not modified. The modification of either LuxRVh or LuxS proteins by the brominated furanones represents an attractive target for the development of antimicrobial therapies, as neither enzyme is present in humans. However, the brominated furanones have also exhibited toxicity against mammalian cells, including human cell lines,50,141 but nevertheless may represent a viable scaffold for the development of less toxic analogs.

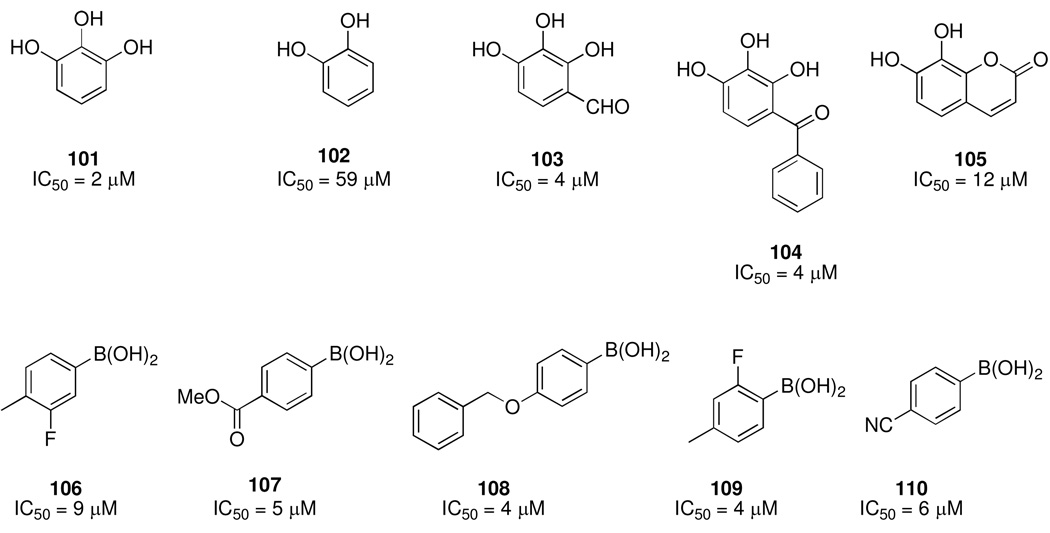

Binghe Wang and coworkers have published a series of screening efforts for the discovery of AI-2 inhibitors, encompassing both the evaluation of small focused libraries and virtual screening techniques. Their first two studies focused on libraries centered around two key structural features of the V. harveyi AI-2 signal: the vicinal diol and the borate diester.142,143 Several cyclic alcohols, including laurencione (86) and MHF (87), have previously been evaluated as AI-2 antagonists, but these efforts had only yielded “hits” with agonist activity.120,122,123 Thus, in their first study, a series of aromatic and five-membered ring diols were evaluated for their ability to inhibit AI-2-based QS in V. harveyi.142 From this screen, five potent inhibitors were discovered, all of which were derived from the pyrogallol structure 101 (Figure 21). However, it was found that pyrogallol derivatives with ionizable groups exhibited diminished activity. A structural rationale for these findings was provided via docking studies with the LuxP protein, which revealed that the pyrogallol structure is capable of the same H-bonding interactions as the natural AI-2 signal, but the presence of an aspartic acid residue in the binding pocket of the LuxP receptor protein may preclude binding by ionized functionalities. These researchers also reported a similar screening process, this time using a series of about 50 boronic acids, and again, several low micromolar inhibitors were uncovered (106–110, Figure 21).143 Similar to the pyrogallol derivatives, ionizable groups on the boronic acids diminished the biological activity. It was also determined that aryl and vinyl boronic acids represented the best inhibitors, likely due to their increased acidity promoting the formation of the tetrahedral borate species found in the natural AI-2 signal. Based on these results, a recent study by Ni et al. focused on the evaluation of several arylboronic acids, and again found several inhibitors with IC50 values in the single digit micromolar range.144 The acidity of the boronic acid again seemed to play a crucial role, as more acidic compounds exhibited increased potency.

Figure 21.

Representative structures of polyphenols and boronic acid AI-2 inhibitors. IC50 values represent concentration required for 50% inhibition of V. harveyi bioluminescence.

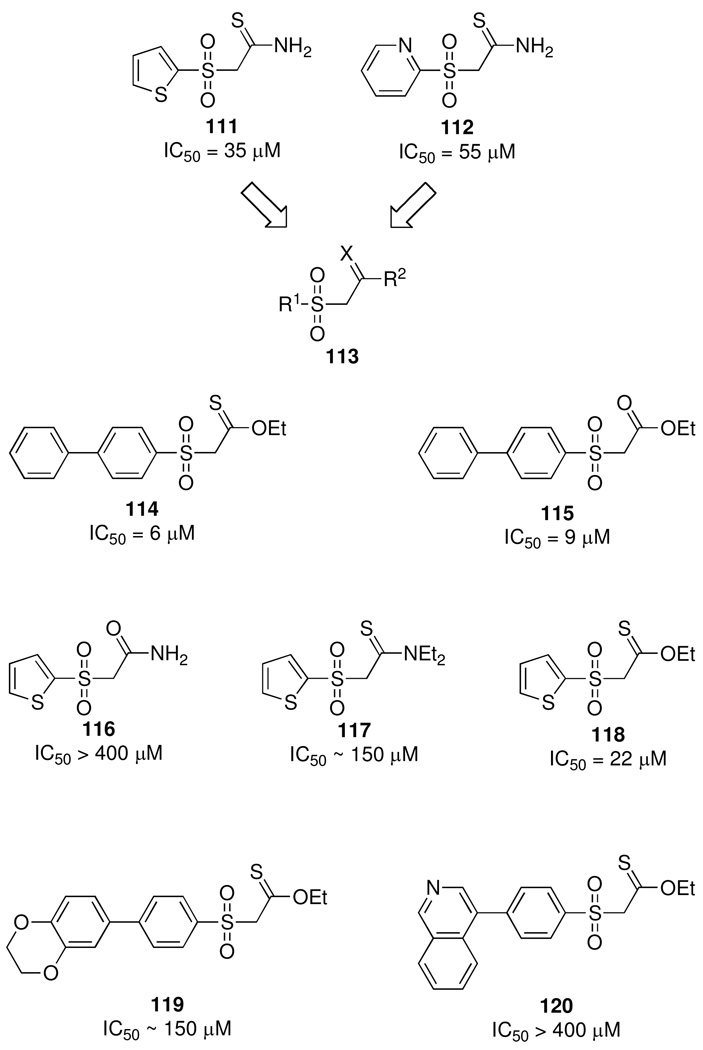

Taking a different approach, and in light of a relative dearth of information pertaining to the development of AI-2 inhibitors, Wang and coworkers later undertook a virtual screening approach to model a total of 1.7 million compounds against the holo form of the LuxP receptor protein;145 42 compounds were identified as potential hits, and 27 of these were evaluated for QS inhibition. Two compounds (111 and 112), both containing a sulfone group, were found to be moderate inhibitors with IC50 values in the range of 35–55 µM, respectively (Figure 22). Interestingly, over half of the hits identified from the in silico screen possessed a sulfone group, likely due to stabilization in the binding site of LuxP imparted by interactions between the oxygen atoms of the sulfone group and active site arginine residues. Furthermore, structural comparisons between active and inactive sulfone-derived compounds revealed the proximity of the sulfone to the aromatic group and the presence of a methylene group between the sulfone and thioamide as critical for activity (113). The two active compounds identified by these in silico efforts also served as lead compounds for the development of other antagonists, and about 40 analogs were designed and synthesized based on the SAR established in the previous study (Figure 22).146 Of these compounds, several displayed more potent inhibition than the original lead compounds (114, 115), and the authors were able to optimize the sulfone/thioamide-derived inhibitors with the conversion of the thioamide to a slightly hydrophobic ester, and the incorporation of a biphenyl system adjacent to the sulfone. The authors later combined these rules and evaluated a library of phenothiazine derivatives, and again discovered potent inhibitors.147

Figure 22.

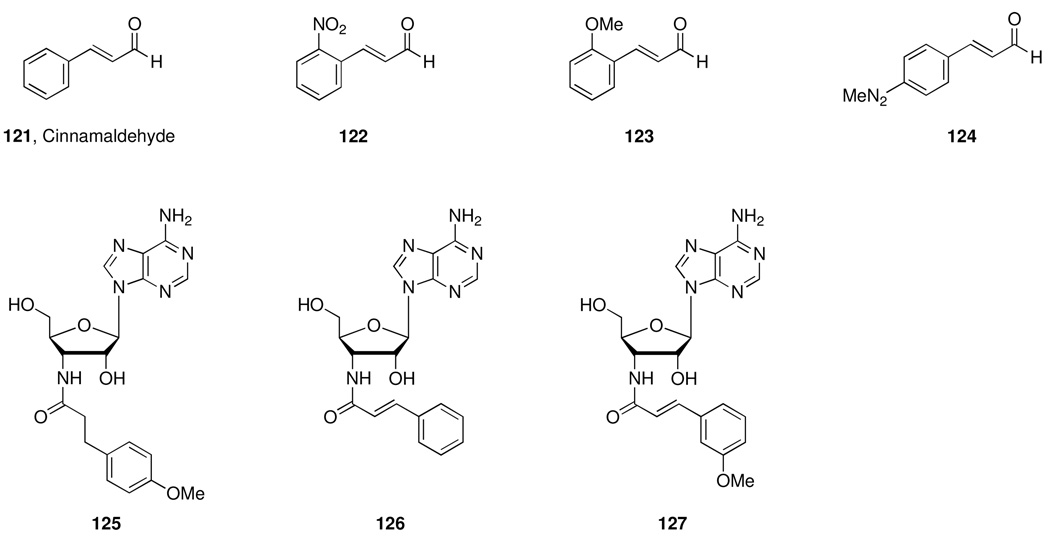

Sulfone based AI-2 inhibitors identified by in silico screening and elaboration of lead compounds. IC50 values represent concentration required for 50% inhibition of V. harveyi bioluminescence.