Standard guidelines for the management of foreign body ingestion may need to be modified for patients who ingest items intentionally. Such individuals are more likely to have mental impairment, psychiatric illnesses, or motivations of secondary gain (eg, prisoners, drug couriers, or “mules”). Their clinical presentation may be delayed and may include multiple foreign bodies. Pica, or the compulsive ingestion of nonfood articles, may be common in those with serious mental impairment or developmental delay. These patients are at risk of complications from expectant management of foreign body ingestion. Physicians should be proactive when managing these patients.

Case Report

We present a 37-year-old woman with a history of cerebral palsy, congenital encephalopathy, spastic quadriplegia, left-sided hemiparesis, and seizure disorder who was admitted from an adult day-care facility, where she had recurrent emesis following the emesis of a large paper towel. The patient had a history of weight loss and iron-deficiency anemia. Five months prior, she had been hospitalized after ingesting a plastic article that had to be removed via rigid endoscopy. These events were complicated by aspiration pneumonia.

The patient's vital signs in the emergency room were stable. She was noncommunicative, except for occasional high-pitched cries. Her oropharynx was clear, and she had no abdominal tenderness.

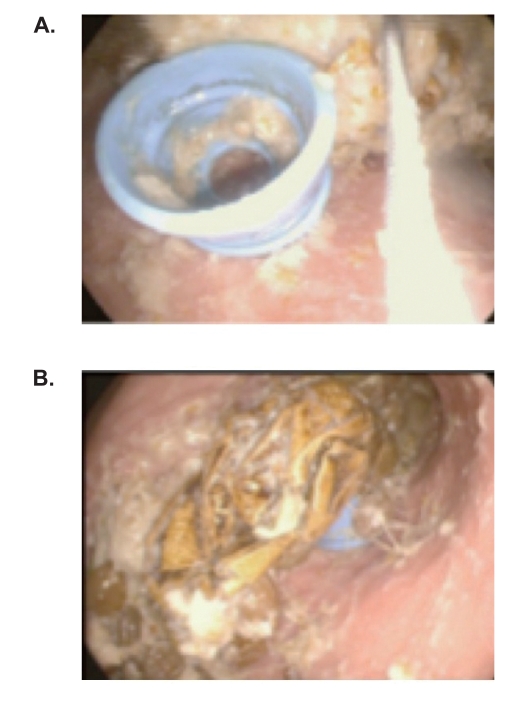

An erect plain radiograph of the abdomen showed a mildly dilated loop of small bowel consistent with subacute small bowel obstruction or focal ileus. Blood work revealed a mild normocytic anemia, thrombocytopenia (127,000 cells/cubic millimeter), mild hyperkalemia (5.8 mEq/L), and elevation of serum creatinine (1.3 mg/dL). Her stool tested positive for the Hemoccult fecal occult blood test. The gastroenterology service recommended endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy), which was performed with endotracheal intubation to protect the patient's airway. Multiple foreign bodies were identified within the stomach. Two towels and an elastic hair band were removed endoscopically. However, the majority of the ingested foreign objects (which included a blue bottle cap and a large gold semi rigid object) were too large for endoscopic removal (Figure 1). The esophageal, gastric, and duodenal mucosa were erythematous and friable, with superficial ulcerations. Subsequently, an exploratory laparotomy was performed to remove the remaining foreign bodies through a gastrotomy incision. No objects were found in the small intestine. The patient had a stormy postoperative course, complicated by aspiration pneumonia. Bronchoscopy revealed evidence of chronic aspiration, including food particles. The patient required a blood transfusion for anemia, and nutritional support was extended.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic view of the bottle cap (A) and plastic sheet (B) in our patient.

Discussion

Current guidelines for management of foreign body ingestion are largely based upon studies from the 1990s, some of which come from the pediatric literature. These studies suggest that only 10–20% of patients require endoscopy (10–20%) or surgery (1%) and report high success rates for endoscopic foreign body removal.1,2 According to more recent guidelines published by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, indications for urgent endoscopic retrieval of esophageal foreign bodies include nonmigration of a sharp object or disc battery, high-grade esophageal obstruction as demonstrated by failure to handle secretions, and foreign body ingestion more than 24 hours prior to presentation.3 However, the interval from ingestion to presentation is often unknown. Endoscopic retrieval of gastric foreign bodies is usually considered when objects are sharp or exceed a certain size that makes passage through the pylorus and duodenal sweep difficult. Reportedly, objects longer than 6 cm in length have difficulty passing through the duodenal sweep, and objects as small as 2 cm in length may become stuck in the pylorus.4,5 Objects that fail to pass through the stomach after several weeks should also be removed endoscopically. Fever, vomiting, and/or abdominal pain raise concerns for possible perforation and require a prompt response. Some guidelines emphasize conservative management of gastric foreign bodies when possible, but this approach may not be the best one in noncom-municative patients.

Management of gastric foreign bodies is largely based upon the physical characteristics of the foreign body. If the ingestion was not witnessed, physicians are dependent upon imaging to detect foreign objects. Plain radiographs may fail to detect plastic, certain types of glass, fish bones, and thin metallic objects.6 They also offer limited data regarding the sharpness of an object. The risk of perforation from an ingested sharp object depends upon its size and orientation, but can be significant.7 If there is any doubt that a sharp object located in the stomach or upper small intestine can pass spontaneously, urgent endoscopic removal is indicated.1

Adults who ingest multiple foreign bodies are more likely to have psychiatric disorders, mental impairment, or motivations of secondary gain. Patients who intentionally ingest these objects have a higher complication rate and greater endoscopic failure.8 These patients are also more likely to have a delayed presentation. An increased risk of perforation has been described in patients with long intervals between ingestion and presentation.9 In a study of foreign body ingestion in an adult population in which 92% of ingestions were intentional, the time from ingestion to presentation was more than 48 hours in over 64% of its 262 cases. The majority of these objects were located in the stomach, proximal to the pylorus, and 76% were greater than 6 cm in length.10

Pica, a condition in which patients crave and consume nonfood items, may be common in those who have mental impairment. Patients with pica are more likely to ingest multiple objects and be repeat offenders. They are also often unable to provide a history. In one study, the mortality rate of 35 pica patients, with 56 total ingestions, was 11%. Surgical intervention was required after 75% of those ingestions.11

Our patient vomited several times prior to hospital-ization. Her emesis may have been due to gastric outlet obstruction. Her well appearance and lack of signs and symptoms were initially deceiving. However, the patient's past history of compulsive foreign body ingestion placed her at a greater risk for perforation, hemorrhage, and bowel obstruction. Uncertainty regarding what she had ingested, her history of marked weight loss, mild anemia, and heme-positive stool led us to perform endoscopy as an aid to management.

Conclusion

The caregivers of mentally impaired patients should have a high level of suspicion for ingested foreign bodies, particularly in those who cannot give a history and those with a prior history of pica and ingestion of multiple objects. Swallowed objects that are too large, numerous, or dangerous for endoscopic retrieval should be removed surgically. However, chronic aspiration pneumonia is common in noncommunicative foreign body ingestors and may complicate recovery from surgery.

References

- 1.Webb WA. Management of foreign body ingestion in the gastrointestinal tract: update. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim JK, Kim SS, Kim JI, et al. Management of foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract: an analysis of 104 cases in children. Endoscopy. 1999;31:302–304. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisen GM, Baron TH, Dominitz JA, et al. Guidelines for the management of ingested foreign bodies. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:802–806. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velitchikov NG, Grigorov GI, Losanoff JE, et al. Ingested foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract: retrospective analysis of 542 cases. World J Surg. 1996;20:1001–1005. doi: 10.1007/s002689900152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knight LC, Lesser TH. Fish bones in the throat. Arch Emerg Med. 1989;6:14–16. doi: 10.1136/emj.6.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng W, Tam PK. Foreign body ingested in children: experience with 1,265 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1472–1476. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vizcarrondo FJ, Brady PG, Nord HJ. Foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:208–210. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(83)72586-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gracia C, Frey CF, Bodai BI. Diagnosis and management of ingested foreign bodies: a ten-year experience. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:30–34. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(84)80380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaves DM, Ischioka S, Felix VN, et al. Removal of foreign body from the upper gastrointestinal tract with a flexible endoscope: a prospective study. Endoscopy. 2004;36:887–892. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palta R, Sahota A, Bemarki A, et al. Foreign body ingestion: characteristics and outcomes in a lower socioeconomic population with predominantly intentional ingestion. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Decker CJ. Pica in the mentally handicapped: a 15-year surgical perspective. Can J Surg. 1993;36:551–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]