Abstract

The study aimed to evaluate the degree of gleno-humeral joint deformation in children with persistent obstetric brachial plexus palsy and its effect on limb function. Computer tomography was performed in 24 children in the mean age of 6.1 years. There were eight boys and 16 girls. Gleno-scapular angle, congruency of gleno-humeral joint and joint deformity according to Waters at all. criteria were measured. The mean functional score according to the Mallet classification system was 12.3 points. The joint was stabile in nine, subluxed in seven and dislocated in nine cases. Gleno-scapular angle in affected joints was 23.3° and in non-affected 4.5°. The glenoid was statistically more retroverted in older children. With more severe posterior incongruence there was statistically greater limitation of passive external rotation, active internal rotation and a poorer functional result according to Mallet. Abnormalities were found also in the humeral head, being deformed and smaller compared to the non-affected side in all cases. Glenoid retroversion, posterior subluxation/dislocation of humeral head and smaller humeral head size are the abnormalities, most often identified in CT examinations. Shoulder function and in particular, passive, external rotation are closely associated with the degree of deformity of the glenoid, as well as with the extent of posterior humeral head dislocation.

Introduction

The natural history of gleno-humeral joints in children with obstetric brachial plexus palsy (OBPP) remains, to a major degree, a rather unknown process. Initial deformation of both the glenoid cavity and the humeral head occurs early, that is, approximately in the fifth month of life, with incomplete restitution of limb function. In the majority of these patients, secondary changes in their joints are identified before the first year of life [1]. Deformation within the shoulder is fairly characteristic and has been described by many authors [1–13]. Most of these reports concentrate on changes in the glenoid cavity—its position in retroversion, posterior edge loss with articular cartilage thinning and glenoid rim lesion in its posterior part. The humeral head is gradually displaced backwards, up to complete dislocation. Moreover, the scapula is raised upwards and hypoplastic, the glenoid cavity is either flattened or absent, the coracoid process is turned downwards, while the acromion may sometimes be conical in shape. The humeral head is rather poorly developed, flattened and hypoplastic. A certain delay is also perceived in the bone age of the proximal end of the humerus. The clavicle may also be shortened, with some deformation on the lateral side.

This study aimed to evaluate the degree of gleno-humeral joint deformation in children with persistent OBPP and its effects on limb function.

Material and methods

A database with information from 186 children with brachial plexus palsy was prospectively used for this study. Of those patients, 24 had shoulder CT performed for shoulder joint evaluation. The age of the children varied between three and 12 years (mean 6.1 years). The group included eight boys and 16 girls. The study addressed the left shoulder in ten and the right shoulder in 14 cases.

The gleno-scapular angle was measured on CT images, obtained in the horizontal plane, to determine the degree of glenoid version, both in affected and normal joints [4, 11]. A line was drawn, linking the most lateral point of the posterior glenoid edge and the most medially localised point of the anterior glenoid edge. Then, another (bisecting) line was drawn, crossing the previous line (at the midpoint of the glenoid) on the one hand, while approaching the medial edge of the scapula on the other. The angle between those two lines was measured in the posterio-medial quadrant, followed by subtraction of 90° from its value. A negative value of that angle revealed glenoid retroversion, while a positive value indicated anteversion. The same bisecting line was then used to determine the humeral head displacement, which, in turn, enabled the definition of either subluxation or complete dislocation in the humeral joint. Then, a further line perpendicular to the bisecting line was drawn, linking the most distant points in front and behind the humeral head. The percentage of humeral head displacement was calculated as a quotient of the distance between the scapular line and the front of the head and of the head diameter multiplied by one hundred (Fig. 1). The line linking points in front and behind the humeral head were also used to measure humeral head size.

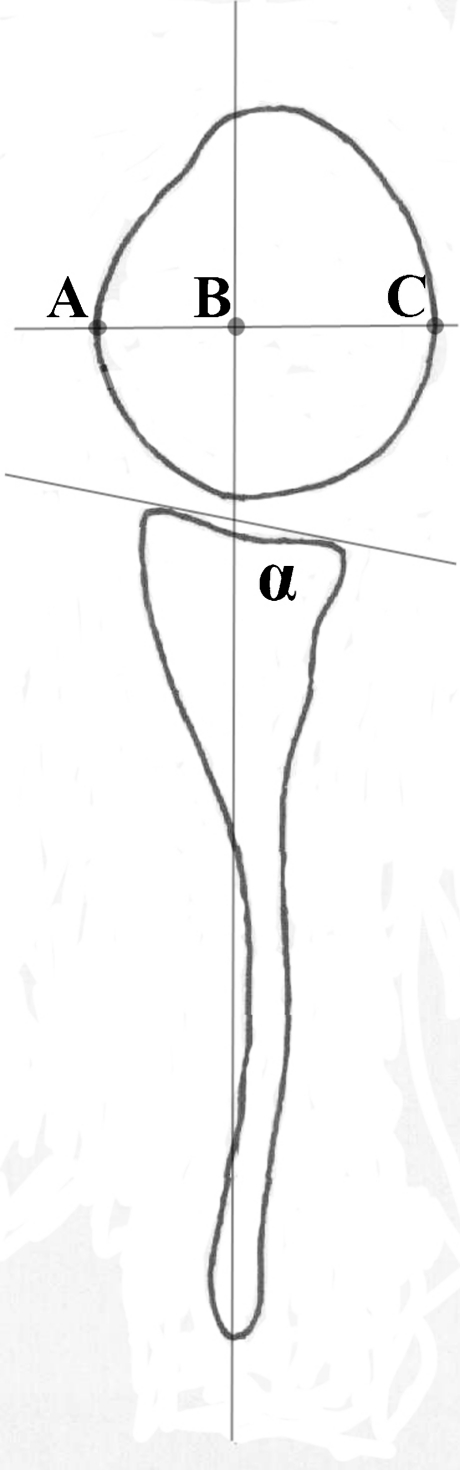

Fig. 1.

Measurement method of gleno-scapular angle (α) and translation of humeral head. Percentage of dislocation of humeral head was measured according to the formula AB/AC x 100%

The Narakas classification was used for the evaluation of nerve root lesions [14]. Nine children were classified into group I (C5, C6 root lesion), while group II (C5, C6, C7 root lesion) comprised ten children and group III (entire plexus palsy) included three children. Two children were classified into group IV (entire plexus palsy with coexisting Horner’s sign).

Gleno-humeral joint deformation was assessed, following the criteria of Waters et al. [13] (Table 1). For statistical analysis, types I and II were evaluated as stable joint, type III as subluxation and types IV and V as complete dislocation.

Table 1.

Assessment of deformity of gleno-humeral joint according to criteria of Waters et al. [13]

| Classification | Description | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|

| Type I, normal glenoid | Less than 5° difference in retroversion between affected and non-affected glenoid | 1 |

| Type II, mild deformity | More than 5° difference in retroversion between affected and non-affected glenoid | 7 |

| Type III, moderate deformity | Posterior subluxation of humeral head—less than 35% of head is anterior to the scapular line | 7 |

| Type IV, severe deformity | Presence of false glenoid | 7 |

| Type V | Severe flattening of humeral head and glenoid with progressive or complete posterior dislocation | 2 |

| Type VI | Posterior humeral head dislocation in infancy | 0 |

| Type VII | Growth arrest of proximal aspect of humerus | 0 |

All the patients were clinically examined. Mallet’s classification [15] was employed for evaluation. Following Mallet’s classification, each patient was assigned a score between 1 and 5 for each of the five clinical parameters. A score of 1 indicated a total lack of function, while 5 meant full movement efficiency. Internal rotation was also evaluated by Mallet’s scale, using score values ranging from 1 to 5. Active and passive movement ranges were measured with a goniometer. The measurement took into account flexion, extension, internal rotation, external rotation, the inferior gleno-humeral angle (the angle between the lateral edge of the scapula and the arm, measured at maximal arm raising) and the posterior gleno-humeral angle (the angle between the arm and the scapular crest, measured at humeral flexion to 90° and in complete adduction).

Statistical analysis

Statistical dependence between joint congruence (stable, subluxated or dislocated joint) and selected clinical and radiological indicators was calculated by means of the ANOVA test. A correlation matrix was used for evaluation of the relationship between the age of children and the acetabulo-scapular angle. Comparison of humeral head size between the affected and normal sides was calculated with Student's t-test. Statistical analysis was performed by means of the Statistical for Windows 7.1 PL program. The values of p < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Results

All patients included in the study demonstrated various limitations in limb function. Clinical evaluation, performed according to Mallet’s classification, revealed score values between 8 and 18 (mean 12.3).

Following the classification of Waters et al., a stable joint was found in nine cases (types I and II), subluxated in seven (type III) and dislocated in nine cases (types IV and V) (Table 1). Acetabular retroversion (the mean acetabulo-scapular angle) in joint with preserved OBPP was 23.3° vs. 4.5° on the normal side. A statistically significant relationship was observed between the age of children and the acetabulo-scapular angle (p = 0.04). Older children presented with a higher degree of acetabular retroversion.

Table 2 presents the mean values of selected clinical and radiological parameters with statistical relationships between those parameters and humeral joint congruence. While it is true that we did not find any statistical relationship between the age of patients and the degree of humeral joint displacement, there were two children with totally damaged humeral joints, flattened at both ends (type V); these were the oldest patients in the studied group (10 and 12 years old) (see Fig. 2a, b).

Table 2.

Mean values of selected clinical and radiological parameters as well as statistical correlations of these parameters and congruency of gleno-humeral joint

| Parameters | Mean values and standard deviations | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Active flexion | 112° ± 34 | 0.49 |

| Passive flexion | 164° ± 10 | 0.61 |

| Active adduction | 109° ± 36 | 0.42 |

| Passive adduction | 163° ± 17 | 0.3 |

| Active inferior gleno-humeral angle | 103° ± 34 | 0.16 |

| Passive inferior gleno-humeral angle | 141° ± 13 | 0.25 |

| Passive posterior gleno-humeral angle | 53° ± 12 | 0.76 |

| Active external rotation | (−23°) ± 21 | 0.3 |

| Passive external rotation | 22° ± 21 | 0.01* |

| Active internal rotation | 2.7 points ± 1.3 | 0.04* |

| Passive internal rotation | 4.5 points ± 0.8 | 0.16 |

| Mallet score | 12.8 points ± 2.8 | 0.01* |

| Narakas classes | 0.7 | |

| Age | 6.1 | 0.9 |

| Gleno-scapular angle | 23.3° ± 2.2 | 0.02* |

* Significant values

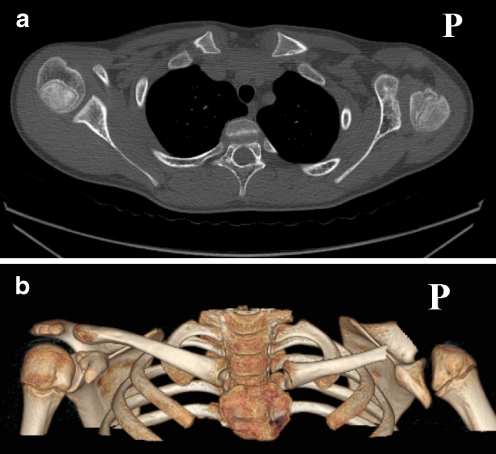

Fig. 2.

a, b Computer tomography image in horizontal plane and 3D reconstruction with removal of acromions, coracoid process and distal part of clavicules of a ten-year-old boy. On the affected right side, severe deformity of glenoid and humeral head. Humeral head is additionally displaced in posterior direction

Deviations from the normal status were also found in the humeral head itself, which was smaller than in the normal joint. The mean humeral head size was 65 mm on the affected side and 81 mm on the normal side (p < 0.001). Humeral head deformation was found in all of the cases.

Discussion

Decreased gleno-scapular angle and posterior humeral head dislocation were the most obvious deformities among the shoulder joints examined. Posterior joint dislocation or subluxation was observed in two out of three patients. In the prevailing majority of those children, glenoid retroversion was found, with some loss of its posterior edge as a result of pressure exerted by the humeral head (Fig. 3). These changes have been described in reports of other authors, in relation to MRI, CT, arthrography and sonographic examinations [4–6, 8–13, 16]. Besides changes in the glenoid, some deviations in humeral head structure were also observed. The proximal end of the humeral head was smaller compared to the normal side in all of the children with deformation of the humeral head. Scaglietti was the first to describe increased retroversion of humeral head in humeral joint affected by OBPP [2]. Van der Sluijs et al. measured the degree of retroversion in MRI scanning [3]. Entire limb shortening, when affected by the disease, has been described by Bea et al. [17].

Fig. 3.

Computer tomography image of both shoulders in an eight-year-old boy. On the right side, the humeral head is smaller, deformed and displaced in the posterior direction. The glenoid is convex and rertroverted because of deficiency of its posterior part

Theoretically, the highest risk of secondary dysplasia of the humeral joint glenoid is associated with the patients with upper nerve root lesions (especially with coexisting lesion of the suprascapular nerve). In those cases, adductor muscles begin to prevail, along with those which rotate the arm inwards, and associated with gradual posterior displacement of the humeral head. In more extensive lesions of nerve roots, the described sequence of events does not occur due to lack of function of particular nerve groups (flail joint). It may then be expected that the joint will remain stable. However, we did not find any relationship between the degree of brachial plexus lesion and joint congruency. Cases have been reported in which, despite a complete recovery of neurological function, a considerable deformity of the shoulder joint was observed. In our material, two patients with total plexus palsy had posterior displacement in humeral joint.

We found in our studies that the more the humeral head was displaced backwards, the more difficult active internal rotation and passive external rotation was, with much worse scores in Mallet’s scale (Graph 1). It seems that this is an effect of highly disturbed muscular balance due to the lack of physical contact between the humeral head and the glenoid and because of the parallel deformation of articular surfaces. Retroversion of the humeral head will always promote internal rotation, while limiting external rotation. Similar observations have been made by Kon et al. They have found a positive correlation between the type of humeral joint deformation, evaluated on preoperative arthrograms, and the deficiency of passive external rotation. The more the humeral head was displaced backwards, the higher was the contracture in internal rotation. It should, however, be noted that the limitation of external rotation need not be associated with deformity of the glenoid. One third of the patients in the studies by Kon et al. had a normal shoulder joint with contracture in internal rotation [8].

Graph 1.

Correlation between congruency of gleno-humeral joint and functional score according to Mallet classification

When analysing our results, we did not find any correlation between the age of the patients and the degree of humeral joint dislocation. At the same time, CT performed in the two oldest children in the study group, revealed considerable flattening of the glenoid and of the humeral head. We also found that in chronic disease, there is a more pronounced retroversion of the glenoid, measured by the glenoid-scapular angle. Waters et al. reported a positive correlation between the age of patients and the progression of shoulder joint deformation. Type V (Table 1) occurred mainly in the children during growth spurts [13].

Pearl et al. recommend arthrography to be performed in children with highly limited external rotation, in which surgical treatment is planned [9]. In their later reports, they compared images obtained in arthrographic examinations, MRI and arthroscopy. They found that MRI is more accurate than arthrography in visualisation of anatomical details. In turn, arthroscopic examinations fairly often revealed irregularities and excavations in the anterior part of the glenoid, which remained invisible in diagnostic imaging scans. Despite that observation, MRI provided much better visualisation of the glenoid shape and of the humeral head setting in the joint [10]. Also worth mentioning should be the possibility of using US imaging in order to determine joint congruence and humeral head deformation. Saifuddin et al. found that in 82% of examined cases, sonographic images are identical with intraoperative diagnoses. Taking into account the relative simplicity of sonographic imaging, low costs and non-invasiveness of the examination, it would seem to be fairly useful in everyday clinical practice [16].

Glenoid retroversion, posterior subluxation/dislocation of humeral head and smaller humeral head size are the deviations from normal status most often identified in CT examinations. Shoulder function and, in particular, passive, external arm rotation are closely associated with the degree of deformation of the glenoid as well as with the extent of posterior humeral head dislocation.

References

- 1.Sluijs JA, Ouwerkerk WJ, Gast A, et al. Deformities of the shoulder in infants younger than 12 months with an obstetric lesion of the brachial plexus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(4):551–555. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B4.11205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scaglietti O. The obstetrical shoulder trauma. Sur Gynecol Obstet. 1938;66:868–877. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sluijs JA, Ouwerkerk WJ, Gast A, et al. Retroversion of the humeral head in children with an obstetric brachial plexus lesion. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84(4):583–587. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B4.12243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman RJ, Hawthorne KB, Genez BM. The use of computerized tomography in the measurement of glenoid version. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(7):1032–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gudinchet F, Maeder P, Oberson JC, Schnyder P. Magnetic resonance imaging of the shoulder in children with brachial plexus birth palsy. Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25(suppl 1):S125–S128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui JH, Torode IP. Changing glenoid version after open reduction of shoulders in children with obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(1):109–113. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200301000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kambhampati SB, Birch R, Cobiella C, Chen L. Posterior subluxation and dislocation of the shoulder in obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:213–219. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B2.17185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kon DS, Darakjian AB, Pearl ML, Kosco AE. Glenohumeral deformity in children with internal rotation contractures secondary to brachial plexus birth palsy: intraoperative arthrographic classification. Radiology. 2004;231(3):791–795. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2313021057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearl ML, Edgerton BW. Glenoid deformity secondary to brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(5):659–667. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199805000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearl ML, Edgerton BW, Kon DS, et al. Comparison of arthroscopic findings with magnetic resonance imaging and arthrography in children with glenohumeral deformities secondary to brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(5):890–898. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200305000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Randelli M, Gambrioli PL. Glenohumeral osteometry by computed tomography in normal and unstable shoulders. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;208:151–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terzis JK, Vekris MD, Okajima S, Soucacos PN. Shoulder deformities in obstetric brachial plexus paralysis: a computed tomography study J Pediatr. Orthop. 2003;23(2):254–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waters PM, Smith GR, Jaramillo D. Glenohumeral deformity secondary to brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(5):668–677. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199805000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narakas AO. Obstetrical brachial plexus injuries. In: Lamb DW, editor. The paralysed hand. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1987. pp. 116–135. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mallet J. Primaute du Iraitement de l’epaule—methode d ‘expression des resultants. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1972;58(Suppl 1):166–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saifuddin A, Heffernan G, Birch R. Ultrasound diagnosis of shoulder congruity in chronic obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84(1):100–103. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B1.11813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bae DS, Ferretti M, Waters PM. Upper extremity size differences in brachial plexus birth palsy. Hand (NY) 2008;3(4):297–303. doi: 10.1007/s11552-008-9103-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]