Abstract

We report a case of corneal deposition of pigments from cosmetic contact lenses after intense pulsed-light (IPL) therapy. A 30-year-old female visited our outpatient clinic with ocular pain and epiphora in both eyes; these symptoms developed soon after she had undergone facial IPL treatment. She was wearing cosmetic contact lenses throughout the IPL procedure. At presentation, her uncorrected visual acuity was 2/20 in both eyes, and the slit-lamp examination revealed deposition of the color pigment of the cosmetic contact lens onto the corneal epithelium. We scraped the corneal epithelium along with the deposited pigments using a no. 15 blade; seven days after the procedure, the corneal epithelium had healed without any complications. This case highlights the importance of considering the possibility of ocular complications during IPL treatment, particularly in individuals using contact lenses. To prevent ocular damage, IPL procedures should be performed only after removing the lenses and applying eyeshields.

Keywords: Complication, Corneal imprinting, Cosmetic contact lens, Intense pulsed-light

Cosmetic contact lenses were initially used for cosmetic purposes by individuals with pathologic abnormalities of the iris or the cornea. However, healthy people have recently started using these lenses [1]. Cosmetic contact lenses make the cornea appear larger than its actual size and can also change the color of the iris. These lenses can also be applied to eyes with no refractive errors; they are freely available without a prescription and can be purchased from many online or brick-and-mortar outlets. Therefore, the users of such lenses are less likely to receive eye examinations or proper lens-care instructions. Inappropriate use of these lenses increases the risk of complications and may result in serious corneal injury [2-4].

Intense pulsed-light (IPL) therapy involves the use of polychromatic light with a broad wavelength spectrum (515-1,200 nm) and is used to treat vascular abnormalities, such as benign cavernous hemangioma, benign venous malformation and essential telangiectasia. This particular therapy is also employed in the treatment of hypertrichosis, facial rhytides and pigmented lesions; therefore, IPL therapy can be also used for non-cosmetic purposes [5]. Nonablative IPL therapy may induce dermatological complications like erythema and hyper- or hypopigmentation. However, to our knowledge, ophthalmologic complications of such therapies have not been reported to date [6,7]. We present a unique case of a patient who wore cosmetic contact lenses without eyeshields during facial IPL treatment, which led to the deposition of the color pigments of the lenses onto the corneal epithelium.

Case Report

A 30-year-old female visited our outpatient clinic due to ocular pain and epiphora in both eyes. Her symptoms had developed soon after undergoing cosmetic facial IPL treatment, which used 555 nm to 950 nm polychromatic light for 90 minutes. The patient had been wearing contact lenses during the entire IPL procedure. The IPL treatment was performed on her face, including her lower eyelids and the skin around her eyes. The patient's symptoms continued to worsen and persisted even after she removed her lenses. The lenses used by this patient were colored dot-matrix and printed lenses showing limbal bands. She had no history of systemic or eye disease. She had been wearing cosmetic contact lenses for four or five days per week for the past three months.

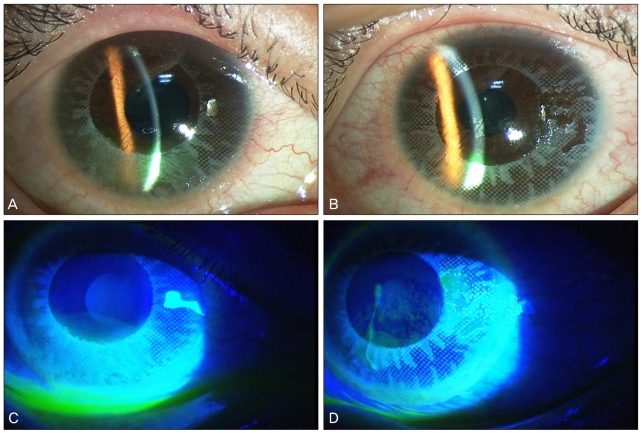

At presentation, her uncorrected visual acuity was 2/20 in both eyes, and intraocular pressure measured using Tonopen was 16 mmHg in the right eye and 14 mmHg in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination revealed conjunctival injection, mild chemosis and deposition of the color pigment of the cosmetic contact lens onto the corneal epithelium. The pattern of deposition matched the pattern on her contact lenses (Fig. 1). Fluorescein dye staining revealed punctate epithelial erosions and corneal epithelial defects in both eyes (right eye, 4 × 3 mm2 inferocentral; left eye, 2 × 2 mm2 inferocentral). Cellular infiltration into the corneal stroma and inflammatory signs in the anterior chamber were not detected in either eye.

Fig. 1.

Slit-lamp photographs at the first examination (A,C, right eye; B,D, left eye). (A,B) Conjunctival injection, mild chemosis and deposition of the color pigments of the cosmetic contact lens onto the corneal epithelium were observed. The pattern of the deposition matched the pattern on the contact lenses. (C,D) Fluorescein-dye staining revealed punctate epithelial erosions and corneal epithelial defects in both eyes.

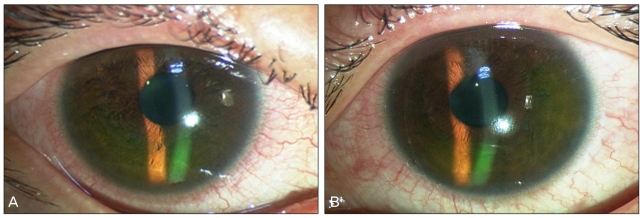

We scraped the corneal epithelium and the deposited pigments using a no. 15 blade under local anesthesia with 0.5% proparacaine (Alcaine®; Alcon, Forth Worth, TX, US). Care was taken not to damage the underlying the Bowman's membrane. Subsequently, we implanted therapeutic lenses in both eyes (Fig. 2). The pigments imprinted on the epithelium were easily removed, and no residual pigment was detected. We prescribed 5% levofloxacin (Cravit®; Santen, Osaka, Japan) topically eight times a day and 0.1% hyaluronic acid (Kynex®; Alcon, Seoul, Korea) every hour.

Fig. 2.

Photographs taken immediately after the excision of the corneal epithelium with the no. 15 blade. The pigments were completely excised. Therapeutic lenses were implanted. (A) Right eye. (B) Left eye.

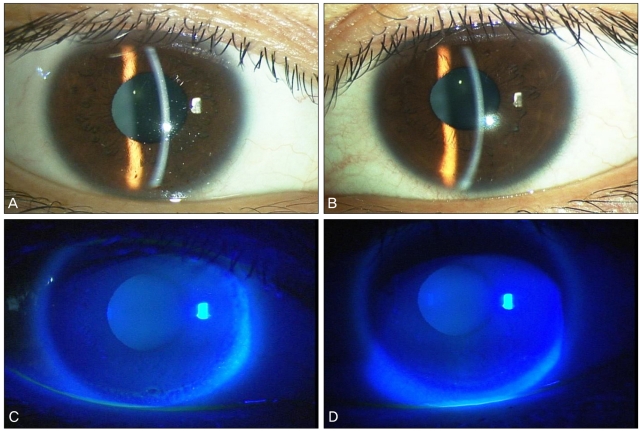

Seven days after the initial treatment, the best-corrected visual acuity of both eyes was 20/25, which was determined using a Snellen's chart. Slit-lamp examination showed that the corneal epithelial defects and corneal erosions had healed without any complications (Fig. 3). Therefore, since considerable improvement was observed, the topical medications were discontinued.

Fig. 3.

Slit-lamp photographs taken on the 7th day after treatment (A,C, right eye; B,D, left eye). (A,B) Corneal epithelial defects and erosions were completely healed. The cornea was clear, and the anterior chamber was clear. (C,D) These are the same photographs after fluorescein staining. An intact epithelium was observed.

Discussion

Cosmetic contact lenses are produced using molecular imprinting and are colored using various methods such as dye dispersion, vat-dye tinting, chemical-bond tinting, and dye printing [1]. The lenses used by our patient were colored using dye printing. Colored lenses were first developed for patients with abnormalities including aniridia or corneal opacity. However, healthy people also currently use colored lenses to change the color or the appearance of their eyes. These lenses are easily available and are sold as cosmetic accessories by unauthorized providers without any medical supervision [2-4].

Cosmetic lenses, like any other lenses, can induce epithelial erosion, corneal neovascularization and infectious keratitis [3,4,8]. Moreover, tinted lenses may hamper night vision and reduce contrast sensitivity [9,10]. The color pigments used in these lenses can also induce allergic reactions or toxic keratopathy and render roughness to the lens surface, thereby adding trauma to the corneal epithelium [11]. A severe sequela of the use of cosmetic contact lenses is infectious keratitis, which has been reported in individuals who wore contact lenses that were previously worn by an infected lens user [2]. Our study is the first report on the deposition of the color pigments of tinted lenses onto the corneal epithelium during IPL treatment.

Generally, IPL therapy involves the use of polychromatic and noncoherent light with a broad wavelength spectrum of 515 nm to 1,200 nm. Polychromatic light with a wavelength spectrum of 555 nm to 900 nm is used in cosmetic surgery. The IPL treatment induces selective photothermolysis by producing heat at the target tissue, i.e., by inducing a photothermal reaction. According to an experimental study, the polychromatic light used in the therapy can heat the target tissue to a temperature of about 80℃ [5].

The ocular complications of IPL therapy have been rarely reported because eyeshields are commonly used during this procedure. In our case, the 90-minute IPL treatment was administered to the patient's face, including the skin around her eyes, without eyeshields. Therefore, the light may have penetrated through the eyelids into the contact lens and may have been absorbed by the color pigments; consequently, the pigments may have separated from the lens and deposited on the corneal epithelium. Although the IPL treatment was not directly administered to the upper eyelids, the polychromatic light may have penetrated into the patient's eyelids, thereby producing heat in the contact lenses. We believe that the pigment of the contact lenses was separated and deposited on the corneal epithelium under the effect of this heat.

Various photoablative treatments are currently being used for cosmetic purposes. Although the dermatological complications of these treatments are well-known, the ocular complications remain to be elucidated. Our case suggests that photoablative treatment may have affected the ocular surface because eyeshields were not used. This case report highlights the importance of considering the possibility of ocular complications during IPL treatment, particularly in individuals using contact lenses. Since no details regarding the effects of light on the lens are currently available, IPL procedures should be performed only after removing the lenses and applying eyeshields to prevent ocular damage.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Phillips AJ, Speedwell L, editors. Contact lenses. 5th ed. London: Butterworth Heinemann; 2007. pp. 519–530. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim TH, Lee JR, Choi KY, et al. Corneal melting and descemetocele resulting from noninfectious keratitis related to the cosmetic contact lenses. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2009;50:774–778. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinemann TL, Pinninti U, Szczotka LB, et al. Ocular complications associated with the use of cosmetic contact lenses from unlicensed vendors. Eye Contact Lens. 2003;29:196–200. doi: 10.1097/00140068-200310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinemann TL, Fletcher M, Bonny AE, et al. Over-the-counter decorative contact lenses: cosmetic or medical devices? A case series. Eye Contact Lens. 2005;31:194–200. doi: 10.1097/01.icl.0000175654.79591.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raulin C, Greve B, Grema H. IPL technology: a review. Lasers Surg Med. 2003;32:78–87. doi: 10.1002/lsm.10145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg DJ, Cutler KB. Nonablative treatment of rhytids with intense pulsed light. Lasers Surg Med. 2000;26:196–200. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9101(2000)26:2<196::aid-lsm10>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bitter PH. Noninvasive rejuvenation of photodamaged skin using serial, full-face intense pulsed light treatments. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:835–842. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gagnon MR, Walter KA. A case of acanthamoeba keratitis as a result of a cosmetic contact lens. Eye Contact Lens. 2006;32:37–38. doi: 10.1097/01.icl.0000177434.64485.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carkeet A. Field restriction and vignetting in contact lenses with opaque peripheries. Clin Exp Optom. 1998;81:151–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.1998.tb06773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiraoka T, Ishii Y, Okamoto F, Oshika T. Influence of cosmetically tinted soft contact lenses on higher-order wavefront aberrations and visual performance. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:225–233. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0973-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi HW, Moon SW, Nam KH, Chung SH. Late-onset interface inflammation associated with wearing cosmetic lenses 18 months after laser in situ keratomileusis. Cornea. 2008;27:252–254. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31815bcd9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]