Abstract

Background As China continues to commit to universal access to HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care services, its HIV/AIDS policies have become increasingly information driven. We review China’s key national-level HIV/AIDS policies and discuss policy gaps and challenges ahead.

Methods We conducted a desk review of key national-level policies that have had a major impact on China’s HIV/AIDS epidemic, and examined recent epidemiological data relevant to China’s HIV response.

Results National-level policies that have had a major impact on China’s HIV/AIDS response include: ‘Four Frees and One Care’; 5-year action plans; and HIV/AIDS regulation. These landmark policies have facilitated massive scaling up of services over the past decade. For example, the number of drug users provided with methadone maintenance treatment significantly increased from 8116 in 2005 to 241 975 in 2009; almost a 30-fold increase. The ‘Four Frees and One Care’ policy has increased the number of people living with AIDS on anti-retroviral treatment from some 100 patients in 2003 to over 80 000 in 2009. However, stigma and discrimination remains major obstacles for people living with HIV/AIDS trying to access services.

Conclusions China’s current national policies are increasingly information driven and responsive to changes in the epidemic. However, gaps remain in policy implementation, and new policies are needed to meet emerging challenges.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, policy, implementation, challenges, China

Introduction

In April 2010, the State Council of the People’s Republic of China officially announced the lifting of its travel ban on people living with HIV/AIDS wishing to enter the country.1 This ban was implemented >20 years ago as one of China’s first key policies for HIV/AIDS control and prevention.2 The announcement reflects China’s current approach to HIV/AIDS: pragmatic solutions to a changing epidemic based on sound scientific information.

China has made significant progress in its HIV response over the past decade. China now has each of the ‘Three Ones’3 recommended by the United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) as key elements supporting a results-based HIV response, (Table 1). In addition to the ‘Three Ones’, China has put into effect key laws that have created an enabling environment for China’s national HIV response, such as the 2006 HIV/AIDS Prevention and Treatment Regulations.

Table 1.

The ‘Three Ones’ coordination of national AIDS responses in China

| UNAIDS ‘Three ones’ | ‘Three ones’ in China | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | One agreed HIV/AIDS action framework that provides the basis for coordinating the work of all partners. | China’s HIV/AIDS action framework is its 5-year action plan for the containment and control of HIV/AIDS. Two 5-year action plans have already been completed (2001–05 and 2006–10), and China is currently in the process of preparing its third 5-year action plan, which will be in effect from 2011 to 2015. |

| 2 | One National AIDS Coordinating Authority, with a broad-based multisectoral mandate. | China’s National AIDS Coordinating Authority is the State Council AIDS Working Committee Office (SCAWCO), established in 2004. |

| 3 | One agreed country-level Monitoring and Evaluation System. | China established its HIV/AIDS Monitoring and Evaluation Framework in 2006, and a unified, web-based Comprehensive Response Information Management System (CRIMS) in 2008. CRIMS is now home to all key HIV/AIDS data, including surveillance and programme monitoring data. |

Moving forward, China faces an array of new and ongoing challenges that will need to be addressed in its new 5-Year Action Plan for the Containment and Control of HIV/AIDS (2011–15). We review key national policies that have guided China’s HIV response at various stages. We also discuss gaps in policy implementation, and challenges ahead as China continues its efforts to achieve universal access to HIV prevention, treatment and care services.

Methods

We performed a desk review of all HIV/AIDS policies issued by the Chinese government since the beginning of the epidemic. We limited our review to national-level policies that have been put in place or revoked over the past 10 years.

We also reviewed available data relevant to selected policies. Data were collected from government reports and papers published in peer-reviewed journals.

Results

An overview of AIDS policies issued against specific HIV/AIDS epidemic phases are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

An overview of China’s HIV/AIDS response

| Phase | Epidemiology | Policy and response |

|---|---|---|

| 1985–88: HIV begins to enter China | During this phase, China’s epidemic was at a very low level, with very few cases reported through the public health system and HIV prevalence not exceeding 1% in any defined subpopulation. By 1988, a total of seven provinces, municipalities and regions had reported 22 HIV/AIDS cases; most of them were foreigners or Chinese residents returning from overseas. | The Chinese government responded with policies aimed at stopping HIV from entering China. Some of the measures taken included: |

| 1989–94: rapid HIV transmission among groups at highest risk | During this phase, HIV began to spread among high-risk groups. In 1989, an outbreak of HIV was detected among injecting drug users (IDUs) in Yunnan province along China’s border with Myanmar, and subsequent investigations revealed that the epidemic had spread among IDUs in neighbouring cities and counties.7,8 By 1994, HIV/AIDS cases had been reported in 22 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities. | China’s response to HIV/AIDS was primarily a policing approach that relied on crackdowns against prostitution and drug use to combat the spread of HIV. At the same time, China’s Ministry of Health began to discuss implementing behavioural interventions in high-risk populations, including providing standardized sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing and treatment for sex workers and their clients during police crackdowns on prostitution.9 |

| 1995–2002: HIV spreads throughout the country | Between 1995 and 2002, HIV spread rapidly and the epidemic became concentrated in high-risk groups.10 In the mid-1990s, an outbreak of HIV transmission among paid plasma donors in several east-central provinces in China was confirmed.11–13 By 1998, all 31 provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities in China had reported HIV/AIDS cases. | Senior government officials in China gradually came to understand the seriousness of the HIV epidemic and the urgency of the response needed. A series of policies and actions were taken at different levels, including:

|

| 2003–present: the number of AIDS cases continues to rise | During this phase, the epidemic has remained concentrated in high-risk groups, with some localities meeting the definition of generalized transmission (HIV prevalence >1% among pregnant women). More and more people living with HIV began to progress to clinical AIDS. | After the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome outbreak in 2003, government support for public health efforts increased dramatically. The HIV response was strengthened by an influx of new funds and high-level political support. Policies and measures developed during this period have included:

|

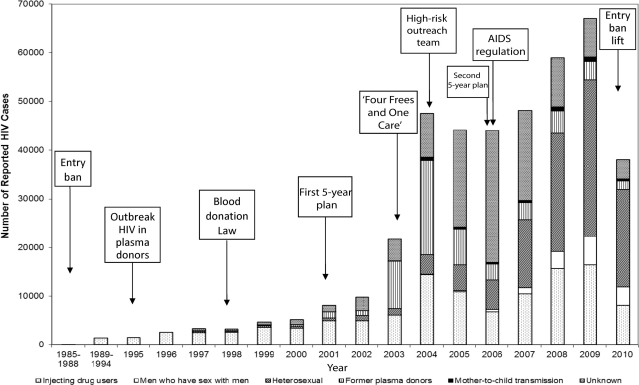

The Chinese government has issued hundreds of HIV/AIDS policies over the past 25 years. We focused on national-level policies that have had a significant impact on China’s HIV/AIDS response. The landmark policies include: the implementation and revocation of China’s travel ban on people living with HIV/AIDS; the Blood Donation Law of 1998; China’s 5-Year Action Plans for the Containment and Control of HIV/AIDS; the ‘Four Frees and One Care’ policy to improve access to treatment and care services; the creation of high-risk behavioural intervention outreach teams; and the 2006 AIDS regulation. These key policies were put in place during different phases of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in China (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

HIV/AIDS cases reported by year and transmission modes and key policies issued at different stages in China 1985–2010. Note: The data for 2010 is only for the first 6 months from January 1 to June 30

Implementation and revocation of China’s travel ban on people living with HIV/AIDS

In June 1985, the first HIV-infected patient, a US citizen, was diagnosed and reported in China. Later that same year, four haemophiliacs were confirmed to have been infected with HIV due to the use of imported blood products.24 By 1988, a total of seven provinces, municipalities and regions had reported 22 HIV/AIDS cases; most of them were foreigners or Chinese residents returning from overseas.

The Chinese government issued a series of early policies focused mainly on blood product safety, case identification and preventing the spread of HIV from infected foreigners entering the country.4 The first HIV/AIDS policy document entitled ‘The Joint Notice on Preventing HIV from Entering China by Restricting Import of Blood Products’ was issued on 17 September 1984.5 In 1986, the Ministry of Health classified HIV/AIDS as a Class B infectious disease notifiable through the national infectious disease reporting system.6

To prevent HIV-infected foreigners from entering into China, a series of policies were issued. Foreign students and research scholars visiting and living in China for >12 months had to submit to HIV testing procedures 1 month after entry into the country. Other foreigners residing or living in China for >12 months had to provide health certificates and were asked to specify if they were infected with HIV/AIDS. Foreigners found to be HIV infected at Chinese cross-border and customs checkpoints were forced to leave the country and were placed under quarantine before departure.2,25–27 To enforce this policy, HIV testing was performed at all entry points into China. Those who meet the criteria for HIV testing at the entry were requested for HIV testing.

Over time, it became clear that HIV-positive foreigners were not driving HIV transmission in China. The first major outbreak of HIV infection in China occurred in 1989 among injecting drug users along China’s border with Myanmar,7 and few infections were transmitted from HIV-positive foreigners entering China.10 In 2004, China’s national surveillance system indicated that HIV prevalence among aliens entering China was 0.147%, with the highest rate along the border between China and Myanmar. Between 2007 and 2009, foreigners accounted for 0.3% of reported HIV infections in China’s HIV/AIDS data system.28

China temporarily lifted its travel ban for special events, such as the Asian Games in 1990, the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995, the Global Fund Board Member Meeting in 2007 and the Olympics in 2008. In April 2010, China permanently lifted its travel ban.1

Blood Donation Law

Between late 1994 and early 1996, outbreaks of HIV infection were identified among commercial plasma donors in regions of central and eastern China.11,12 The scale of transmission and the resulting devastation led to one of the worst tragedies of the global HIV pandemic. Early small-scale surveys indicated that the epidemic was serious, but the true scope of transmission was largely unknown until 1996, when a large-scale survey was carried out among plasma donors in Fuyuan, Anhui Province, showing an HIV prevalence of 12.5%.12

To respond to this crisis, China’s Blood Donation Law was drafted in 1996 and enacted in 1998. The most important components of the law highlight voluntary donation and prohibit repeated commercial donation. At same time, nationwide blood collection facilities were established and manual collection of blood or plasma was prohibited.

Since the enactment of the Blood Donation Law in 1998, 18 cases of HIV infection caused by transfusion occurred in 2002 and were reported in 2008; these occurred as a result of using repeat paid blood donors.29 It is not clear if there have been any other cases of HIV infection caused by transfusion. Although it is possible that HIV transmission may occur as a result of HIV-contaminated blood collected from an HIV-positive voluntary donor during the window period of HIV infection, the number of voluntary donors screening positive for HIV is low and the number who may be in the window period of infection is even lower.

China’s 5-year action plans for the containment and control of HIV/AIDS

Since 1995, HIV spread more quickly throughout China.10 By 1998, all 31 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions in Mainland China reported HIV cases.10

To respond to the changing HIV/AIDS epidemic, several key ministries, including health, finance, public security, justice, and the development commission, met to discuss instituting supportive policies for condom promotion, needle exchange and methadone maintenance programmes. The language of early documents was carefully selected to avoid condoning ‘social evils’, such as prostitution and drug use. Terms such as condom social marketing, needle social marketing and community-clinic-based therapeutic treatment for drug users were used to describe HIV prevention measures that were incorporated into China’s first 5-year action plan (2001–05).16

China’s first 5-year action plan was a policy milestone in terms of supporting effective policies for condom promotion, methadone maintenance and needle exchange. One of most important policy directions laid out in the first 5-year action plan was pilot testing of harm reduction strategies, including methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) and needle exchange programmes.30,31 However, implementation of the plan was not adequately budgeted, weakening its impact, particularly in the first 3 years, between 2001 and 2003. After the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome outbreak in 2003, public health rose to the top of China’s policy agenda, and funding for the HIV/AIDS 5-year action plan increased.18

China’s second 5-year action plan (2006–10) was drafted in a more supportive political environment in which public health was given a higher priority. First, there was much stronger political commitment and financial commitment for controlling HIV/AIDS from Chinese Central Government. In 2003, a new administration led by President Hu Jintao, Premier Wen Jiabao and Vice Premier and the then Health Minister Wu Yi put the implementation of evidence-based HIV policies high on the national agenda.18 Secondly, China’s ‘Four Frees and One Care’ policy to increase access to anti-retroviral therapy (ART) was announced in late 2003 and had greatly facilitated implementation of HIV prevention, treatment and care and support.

The second 5-year action plan set more specific and ambitious targets, particularly for prevention programmes for marginalized groups, such as drug users, female sex workers and men who sex with men. For example, one of the 2010 targets was for HIV prevention programmes to achieve >90% coverage of the ‘floating population’ (such as migrant workers) and people with high-risk behaviours. Another target was set to establish MMT clinics in counties and cities with more than 500 drug users registered with the Public Security Bureau, and for ≥70% of opiate users to receive MMT services. This target has greatly facilitated the scaling up of the MMT programme in China; for example, the number of drug users receiving methadone increased from 8116 in 2005 to 241 975 in 2009, almost a 30-fold increase.32

Other targets included:

achieving 50% coverage of needle and syringe exchange programmes;

reducing the needle/syringe sharing rate among IDUs to <20%;

increasing the proportion of people with high-risk behaviour who have basic HIV knowledge to at least 90%;

increasing the condom usage rate to ≥90% among high-risk groups.20

The plan also set specific targets for treating AIDS patients. Some of these targets included:

at least 80% of AIDS patients satisfying the treatment criteria should have received ART by 2010;

mother-to-child transmission prevention services should be available in ≥90% of cities and counties; and

more than 90% of HIV-positive mothers should have received prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services.20

The evaluation of the second 5-year action plan will take place next year. China’s 2010 UNGASS Country Progress Report33 suggested that China’s AIDS programme is approaching specific targets set in its second 5-year plan.

The ‘Four Frees and One Care’ policy

The massive outbreaks of HIV infection that occurred in central China among paid plasma donors around the mid-1990s led to a huge demand for HIV/AIDS treatment and care services as more and more people became ill and died. At the United Nations High-Level Special Meeting in September 2003, the Chinese government announced five commitments in the fight against HIV/AIDS, later known as the ‘Four Frees and One Care’ policy. These commitments included:

free anti-retroviral drugs to AIDS patients who are rural residents or people without insurance living in urban areas;

free voluntary counselling and testing;

free drugs to HIV-infected pregnant women to prevent mother-to-child transmission, and HIV testing of newborn babies;

free schooling for AIDS orphans and children from HIV infected families; and

care and economic assistance to the households of people living with HIV/AIDS.

The ‘Four Frees and One Care’ policy has had a significant impact upon the HIV/AIDS epidemic in China. First, it resulted in a significant increase in the number of people being tested for HIV34. Before 2003, less than 22 000 newly identified HIV infections were reported each year. After 2004, over 44 000 newly identified HIV infections were reported each year (Figure 1). Secondly, it resulted in a significant increase in the number of AIDS patients receiving free anti-retroviral treatment; for example, increased from 100 in 2003 to over 80 000 in 2009,22 and it helped reduce AIDS mortality among those on ART.35 Thirdly, it increased the number of pregnant women screened for HIV infection and receiving PMTCT services. Fourthly, all AIDS orphans have been taken care of by either relatives, or neighbour or local government social welfare programmes.

The ‘Four Frees and One Care’ policy has also significantly reduced stigma in local communities, particularly in areas where the epidemic was driven by contaminated plasma collection.36

High-risk behavioural intervention outreach teams

In 2004, as the primary mode of HIV transmission began to shift from injecting drug use to high-risk sexual behaviours, the Chinese Ministry of Health announced the establishment of high-risk behavioural intervention teams at all levels of the public health system.37 The primary function of these teams is to conduct an outreach programme among sex workers, men who have sex with men, and migrant labourers to reduce the risk of HIV sexual transmission among these high-risk groups. Intervention teams have increased the reach of HIV prevention programmes. On average, these teams have reached about 460 000 female sex workers and 120 000 men who sex with men per month.38

National HIV/AIDS regulation

In early 2006, the Chinese government issued the national HIV/AIDS regulation to define the roles and responsibilities of government, civil society and people living with HIV/AIDS. This was the first law in China to highlight protection of human rights of people living with HIV/AIDS, including the right to marry, to access health-care services, to enjoy equal employment opportunities and to receive schooling. The regulation has laid a legal base for effective but sensitive prevention measures, such as condom promotion, MMT and needle exchanges.

However, implementation of HIV/AIDS regulation varies in different articles and in different places. The most significant gap relates to stigma-related rights for receiving medical services and employment. On 27 August 2010, the first case of a law suit concerning HIV-related stigma for employment was reported and has generated great discussion and concern.39 The most frequent cases of discrimination that people living with HIV/AIDS face are when seeking medical care in clinical settings. There is still a long way to go to achieve the goal of zero stigmas in Chinese society, though HIV/AIDS regulation is in place.

Discussion

China now has national laws, policies, action plans, surveillance systems and monitoring and evaluation systems in place to support its HIV/AIDS response, as well as a government body with the authority to coordinate different sectors. HIV/AIDS policies and action plans are responsive to the increasing wealth of epidemiologic data available, and a massive scaling up of services has taken place over the past decade.

Though efforts have been made to achieve universal access to prevention, treatment, care and support services, a number of important gaps exist in the implementation of China’s HIV/AIDS policies. First, despite the increased coverage of HIV testing services, too many people remain unaware of their HIV status. By the end of 2009, there were 326 000 cumulative cases of HIV/AIDS reported, and an estimated 740 000 people living with HIV/AIDS in China.40 This means that less than half of the people living with HIV/AIDS are aware of their HIV status, and hence unable to receive needed HIV prevention, treatment and care services.

Secondly, AIDS mortality remains a major problem despite expanded ART programmes because too many people are receiving HIV testing services after they have already progressed to AIDS. Deaths related to HIV/AIDS increased from 5544 in 2007 to 9748 in 2008 and 12 287 in 2009.23,41,42 The majority of reported deaths occurred among people who had progressed to AIDS by the time they were tested for HIV, and hence many missed the opportunity to use life-saving ART.

Thirdly, many people remain unwilling to be tested for HIV. After China launched its mass screening campaign in 2004–05, it was presumed that most of people infected with HIV via plasma donation or transfusion were already identified. However, there have been between 1136 and 1614 HIV cases and 2295–3003 AIDS cases newly identified and reported each year between 2007 and 2009.23,41,42

Fourthly, important gaps remain in the implementation of national policies at the provincial and sub-provincial levels. Some local governments do not fully implement national HIV/AIDS policies.37,38 Interventions among high-risk groups often lack sufficient coverage, depth and frequency to have an impact on the course of the epidemic.

Fifthly, in some places, the rate of consistent condom use is low among sex workers and their clients.

Sixthly, coverage of PMTCT services and ART programmes remain too low, and the quality of services needs to be improved.

Seventhly, the involvement of civil society needs to be increased. Non-governmental organizations alone lack the necessary capacity and experience to respond to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, but they can play a vital role in the HIV response. Enterprises and individuals have often limited understanding of the importance of HIV/AIDS and are not fully motivated to participate in HIV/AIDS activities.

New policies are needed to achieve the goals of universal access and respond to the changing dynamics of China’s HIV epidemic. New policy areas of special emphasis in China’s new 5-year action plan should include reducing stigma and discrimination, encouraging greater civil society participation, HIV routine testing, partner notification, management of opportunistic infections and co-infections with tuberculosis and hepatitis, and treatment of the mobile population.

Recent data have shown that HIV transmission is gradually shifting away from being caused by injecting drug use and more by sexual contact. In 2007, the proportion of estimated HIV infections associated with sexual transmission exceeded that of injecting drug use.43 HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men is increasing rapidly. Between 2005 and 2009, the proportion of HIV infections associated with male-to-male sexual transmission increased from 0.4 to 8%, representing a 20-fold increase.

To address these challenges, the strategies and policies for HIV/AIDS response at the grass-roots level are being explored and strengthened in several ways. Policies and mechanisms that encourage grass-roots governmental department support are being promoted. The participation of grass-roots social and civil society groups is encouraged. Improvements are being made on the social security system, grass-roots health-service system, and basic health-care service provision and drug supply.40,43 Plans and models of HIV/AIDS interventions that are appropriate to local communities are being developed. Accessibility and coverage of testing, interventions, treatment, PMTCT, care and support and other services are being enhanced. Community-based models with multisectoral accountability are being established. Sustainable HIV/AIDS services are being promoted. Developing evidence-based decision making processes and policies and strategies is vital to the success of China’s future HIV response.

Conclusion

As the epidemic shifts towards being caused increased sexual transmission, China will continue to develop and improve its information-driven policy response to HIV/AIDS. Empirically based scientific information will dictate which policies will be effective and sufficient to turn the tide of the HIV epidemic. Greater emphasis may need to be placed on community-based and multisectoral involvement as a comprehensive response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Sound policy decisions will be enacted as China works to ensure universal access to HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment, care and support services.

Funding

Chinese Ministry of Health National AIDS Program (131-08-105-02); US National Institute of Health, Fogarty International Center and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (to Multidisciplinary HIV and TB Implementation Sciences Training in China, China ICOHRTA2, National Institutes of Health Research Grant 5U2R TW06918-07, Principal Investigator Z.W.).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

KEY MESSAGES.

Landmark national-level AIDS policies, e.g., ‘four frees and one care’, have facilitated massive scaling up of prevention, treatment and care services over the past decade in China.

China's current national policies are increasingly information driven and responsive to changes in the epidemic.

Gaps remain in policy implementation, and new policies are needed to meet emerging challenges.

References

- 1.The State Council of China. Rules for Implementation of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Control of the Entry and Exit of Aliens. Beijing: The State Council of China; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Rules for Implementation of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Control of the Entry and Exit of Aliens. Beijing: Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS. The ‘Three Ones’- Principles for the Coordination of National AIDS Responses. 2004. http://www.unaids.org/en/CountryResponses/MakingTheMoneyWork/ThreeOnes/default.asp (10 October 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health of China. Report on Strengthening Surveillance to Prevent Imported Cases of HIV/AIDS. Beijing: Ministry of Health of China; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health of China. Notice on Banning Import of Blood Products such as Factor VIII. Beijing: Ministry of Health of China; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Health of China. Notice on Strengthening HIV/AIDS Management. Beijing: Ministry of Health of China; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma Y, Li Z, Zhang K, et al. Identification of HIV infection among drug users in China. Chinese J Epidemiol. 1990;11:184–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng XW, Zhang JP, Tian CQ, et al. Cohort study of HIV infection among drug users in Ruili, Longchuan and Luxi of Yunnan Province, China. Biomed Environ Sci. 1993;6:348–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministry of Health of China, Ministry of Public Security of China. Notice on Providing Compulsory Testing and Treatment of Sexual Transmitted Diseases for Sex Workers and their Clients. Beijing: Ministry of Health of China; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Z, Rou K, Cui H. The HIV/AIDS epidemic in China: history, current strategies and future challenges. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16(3 Suppl A):7–17. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.3.5.7.35521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Z, Liu Z, Detels R. HIV-1 infection in commercial plasma donors in China. Lancet. 1995;346:61–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92698-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Z, Rou K, Detels R. Prevalence of HIV infection among former commercial plasma donors in rural eastern China. Health Policy Plan. 2001;16:41–6. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu Z, Dong N, Guo W. Discovery and control of the HIV/AIDS epidemic among plasma donors in China. In: Li LM, Zhan SY, editors. Epidemiological Research Cases in China. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2008. pp. 153–64. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health, State Development Planning Commission, Ministry of Science and Technology, Ministry of Finance. China's Medium and Long-Term Plan on Prevention and Control of HIV/AIDS. Beijing: Chinese Ministry of Health; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ministry of Health of China. Working Duty in HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control for Related Ministries, Committees, Administrations and Social Groups. Beijing: Ministry of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.State Council of P.R. China. China's Action Plan for Reducing and Preventing the Spread of HIV/AIDS (2001 - 2005) Beijing: State Council Office; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.State Council of the People’s Republic China. Notice on Strengthening AIDS Prevention, Treatment and Care Programs. Beijing: State Council of the People's Republic China; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Z, Sullivan SG, Wang Y, Rotherum-Borus MJ, Detels R. The evolution of China’s response to HIV/AIDS. Lancet. 2007;369:679–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60315-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.State Council of P.R. of China. Regulations on AIDS Prevention and Treatment. Beijing: State Council Office; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.State Council of P.R. China. Action Plan on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Containment (2006-2010) Beijing: State Council Office; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Health of China, Ministry of Public Security of China, Ministry of Justice of China. Notice on HIV Screening of Inmates of Prisons and Detoxification Centers. Beijing: Ministry of Health of China; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministry of Health of China. Notice on HIV Screening of Former Plasma Donors. Beijing: Ministry of Health of China; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. [Annual Report of HIV/AIDS/STD Prevention, Treatment and Care in China in 2009] Beijing: National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeng Y, Wang B, Zheng X, et al. [Adenovirus Antibody testing in serum of hemophiliacs patients] Chinese J Virol. 1986;6:97–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.State Education Commission of China, Ministry of Health of China. Notice on Performing HIV Test for Foreign Students. Beijing: State Education Commission of China, Ministry of Health of China; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ministry of Health of China, Ministry of Public Security of China. Provisions Concerning the Provision of Health Certificate by Foreigners Seeking Entry. Beijing: Ministry of Health of China; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ministry of Health of China, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China, Ministry of Public Security of China, et al. Several Provisions Concerning HIV Surveillance and Management. Beijing: Ministry of Health; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mao Y, Wu Z, Poundstone K, et al. Development of a unified web-based national HIV/AIDS information system in China. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(Suppl 2):ii79–89. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J. Doctor did not know blood donation law causing 19 patients infected with HIV in Bei-An, Heilongjiang. 2007. http://news.xywy.com/news/tjxw/20070625/121395.html (4 October 2010, date last cited) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sullivan SG, Wu Z. Rapid scale up of harm reduction in China. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:118–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pang L, Hao Y, Mi G, et al. Effectiveness of first eight methadone maintenance treatment clinics in China. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):S103–S107. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304704.71917.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin W, Hao Y, Sun X, et al. Scaling up the national methadone maintenance treatment program in China: achievements and challenges. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(Suppl 2):ii29–37. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China. China 2010 UNGASS Country Progress Report (2008-2009) Beijing: Ministry of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu Z, Sun X, Sullivan SG, Detels R. Public health. HIV testing in China. Science. 2006;312:1475–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1120682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang F, Dou Z, Ma Y, et al. Five-year outcomes of the China National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:241–51, W-52. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao X, Sullivan SG, Xu J, Wu Z China CIPRA Project 2 Team. Understanding HIV-related stigma and discrimination in a ‘blameless’ population. AIDS Educat Prevent. 2006;18:518–28. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.6.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ministry of Health of China. Announcement on Establishing High Risk Behavioral Intervention Team Among all Level of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in China. Beijing: Ministry of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rou K, Sullivan SG, Liu P, Wu Z. Scaling up prevention programs to reduce the sexual transmission of HIV in China. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;(Suppl 2):ii38–46. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The First Law Suit to AIDS Discrimination in China. 2010. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/hqgj/jryw/2010-09-03/content_811199.html (11 October 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ministry of Health of China, UNAIDS, WHO. The Estimation of HIV/AIDS in China in 2009. Beijing: Ministry of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. [Annual Report of HIV/AIDS/STD Prevention, Treatment and Care in China in 2007] Beijing: National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. [Annual Report of HIV/AIDS/STD Prevention, Treatment and Care in China in 2008] Beijing: National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 43.State Council AIDS Working Committee Office, UN Theme Group on AIDS in China. A Joint Assessment of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Treatment and Care in China (2007) Beijing: China Ministry of Health, 1 December 2007. [Google Scholar]