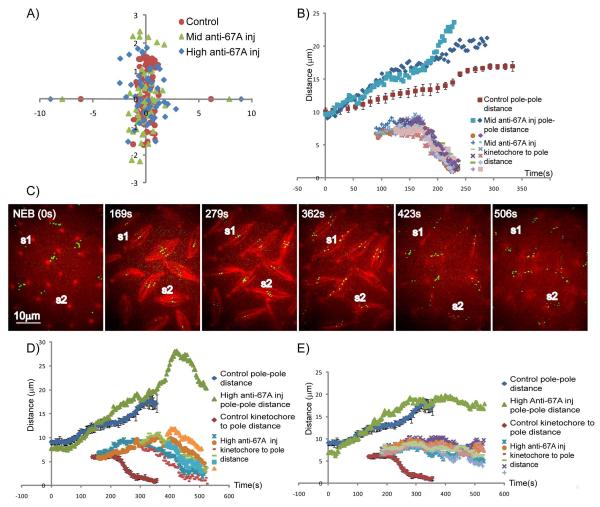

Figure 5. Chromosome congression and anaphase A are perturbed by anti-KLP67A antibody injection.

(A) Positions of metaphase kinetochores in: (i) control (red); (ii) “mid” anti-KLP67A (green); and (iii) “high” anti-KLP67A (blue) injected embryo spindles, showing that KLP67A inhibition causes kinetochores to scatter over a wider range relative to the spindle equator. Average pole positions are plotted along x-axis. (B) Pole-pole distance and kinetochore-to-pole distances as a function of time for two representative spindles injected with “mid” concentrations of anti-KLP67A in comparison with controls (red). After “mid” anti-KLP67A injection, anaphase A started at the normal time, kinetochores moved synchronously toward the pole, and chromosome segregation was completed. Based on their different behavior in anaphase B spindle elongation, spindles injected with mid concentration of anti-KLP67A could be categorized into two groups. In the first group (resembled by pole dynamics plotted in blue), the onset of anaphase B is blurred because there’s no significant difference between pre-anaphase B and anaphase B spindle elongation rate. In the second group (resembled by the pole dynamics plotted in light blue), the anaphase B spindle elongation rate is usually higher than control, the timing of anaphase A and anaphase B is perturbed. (C, D ,E) show that “high” anti-KLP67A injection caused slow or incomplete kinetochore to pole movement (C, MT: red; CID-GFP: green), which could be categorized into two groups. In the first group (exemplified by spindle S1 in C and the data plotted in D), kinetochores moved toward the poles in a non-synchronous manner at a slower rate than normal but were nonetheless able to reach the poles to complete their separation. In the second group (exemplified by spindle S2 in C and the data plotted in E), kinetochore-to-pole movement stopped prematurely after an initial phase of separation. Noticeably, in both groups, anaphase A started later than in control spindles.