Abstract

Heterotopic gastric mucosa patches are congenital gastrointestinal abnormalities and have been reported to occur anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anus. Complications of heterotopic gastric mucosa include dysphagia, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, upper esophageal ring stricture, adenocarcinoma and fistula formation. In this case report we describe the diagnosis and treatment of the first case of esophago-bronchial fistula due to heterotopic gastric mucosa in mid esophagus. A 40-year old former professional soccer player was referred to our department for treatment of an esophago-bronchial fistula. Microscopic examination of the biopsies taken from the esophageal fistula revealed the presence of gastric heterotopic mucosa. We decided to do a non-surgical therapeutic endoscopic procedure. A sclerotherapy catheter was inserted through which 1 mL of ready to use synthetic surgical glue was applied in the fistula and it closed the fistula opening with excellent results.

Keywords: Gastric heterotopy, Esophago-bronchial fistula, Ectopic gastric mucosa, Heterotopic gastric mucosa, Esophagus, Esophageal fistula therapy

INTRODUCTION

Ectopic gastric mucosa (EGM) can occur in the fore-, mid- and hindgut and, conceivably, at any of their derivatives[1]. The origin of EGM is either heterotopic (congenital) or metaplastic (acquired). The reported incidence of EGM in the endoscopic literature ranges from 0.29% to 10% but an incidence of up to 70% has been reported in autopsy studies[2]. Heterotopic gastric mucosa (HGM) patches are congenital gastrointestinal abnormalities and have been reported to occur anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anus[1-5].

HGM in the esophagus is thought to arise from gastric precursor cells that remain after incomplete replacement of the original stratified columnar epithelium lining the embryonic esophagus by stratified squamous epithelium[6-8].

Diagnosis of HGM is often difficult and requires experience and a high degree of suspicion. At endoscopy, the HGM appears as a mainly flat or slightly raised, well circumscribed red-orange salmon-colored patch. This is mainly a solitary patch but can be multiple measuring from a few millimeters to several centimeters[9]. Complications of HGM patches include dysphagia, upper gastrointestinal bleeding[10], stricture[11] and fistula formation[12], upper esophageal ring[13] and adenocarcinoma[14-15]. Interestingly, HGM in the duodenum may also manifest as dyspepsia[16].

CASE REPORT

A 40-year old former professional soccer player was referred to our department for further investigation of a recently diagnosed esophago-bronchial fistula. Fistula diagnosis was made during investigation of relapsing episodes of acute dyspnea and upper abdominal discomfort during the previous six months.

The patient’s family history was unremarkable except that his father was treated for tuberculosis twenty years previously. The patient was diagnosed with allergic rhinitis and mushroom allergy; he never smoked and rarely drank alcohol. For the last twenty years the patient had suffered from relapsing episodes of lower respiratory tract infections which were treated with antibiotics and one year ago he underwent coronary artery stenting.

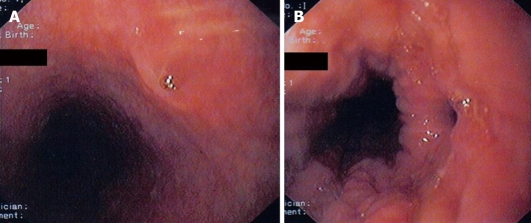

The patient had previously been investigated for these acute dyspnea episodes and, as cardiologic and other routine evaluations were negative, he was started on bronchodilators and antibiotics without subsequent improvement. As his symptoms persisted, the patient developed stress-related sleeping disturbances and panic disorder and was followed up by a psychiatrist. After some weeks the patient consulted a gastroenterologist. As he could not tolerate endoscopy he underwent baium follow through which revealed an esophagobronchial fistula tract (Figure 1) and he was referred for further investigation and treatment.

Figure 1.

Barium follow through of the esophagus revealing the esophago-bronchial fistula.

On admission clinical examination was negative. The patient was on antidepressants, beta-blockers, clopidogrel, aspirin and simvastatin. Laboratory tests revealed nothing. Serum angiotensin converting enzyme was within normal limits. Mantoux was 18 mm at 48 h. Differential diagnosis included congenital fistula, active or latent tuberculosis, granulomatous diseases, neoplasia and possible blind trauma. Trauma probability was immediately excluded as the patient had never had any kind of endoscopy or history of complicated esophageal foreign body ingestion. Congenital fistula was improbable as the patient had been free of symptoms until twenty years of age. Thorax high resolution computed tomography showed infiltrations in the right lobe in contact with the mediastinum but not of lymph nodes and Tc-99m pertechnetate scintigraphy proved of no help.

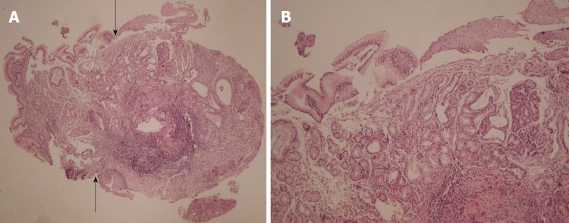

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed with deep sedation. In the mid esophagus at 28 cm from the mouth incisors the proximal opening of the fistula tract was revealed and biopsies were taken (Figures 2A and B). A small gastro-esophageal hernia extended from 40-42 cm from mouth incisors with concomitant mild esophagitis but not Barrett’s esophagus. In the stomach there was mild gastritis with some erosions and biopsies were taken. The first and second part of the duodenum was normal. Bronchoscopy including cytology, PCR and cultures for mycobacterium tuberculosis and other pathogens were negative.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic view of the proximal opening (open and closed) of the esophago-bronchial fistula caused by heterotopic gastric mucosa. A: Closed; B: Open.

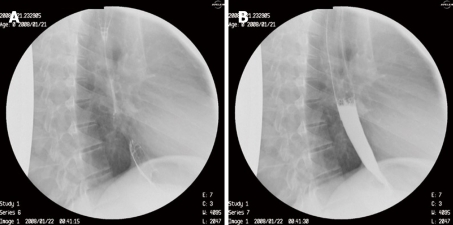

Microscopic examination of the biopsies taken from the esophageal fistula revealed the presence in the lamina propria of mucus secreting cardiac-type glands and of fundic-type glands containing both parietal and chief cells. Furthermore, the mucosa was covered by tall, columnar foveolar epithelium, which at the edges merged with the adjacent esophageal stratified squamous epithelium. Goblet cells were not identified. There was no evidence of dysplasia. Microorganisms with the morphological characteristics of Helicobacter pylori were not observed with Giemsa special stain (Figures 3A and B).

Figure 3.

Heterotopic gastric mucosa in middle esophagus. A: Arrows denote the transition between the columnar foveolar epithelium and the esophageal stratified squamous epithelium (H&E, × 40); B: Columnar epithelium merges with stratified squamous epithelium. At the lamina propria cardiac and fundic-type glands are evident (H&E, × 200).

In the biopsies from the antral gastric area, microscopic findings consistent with chronic active gastritis were noted. Helicobacter pylori micro-organisms were observed with Giemsa special stain.

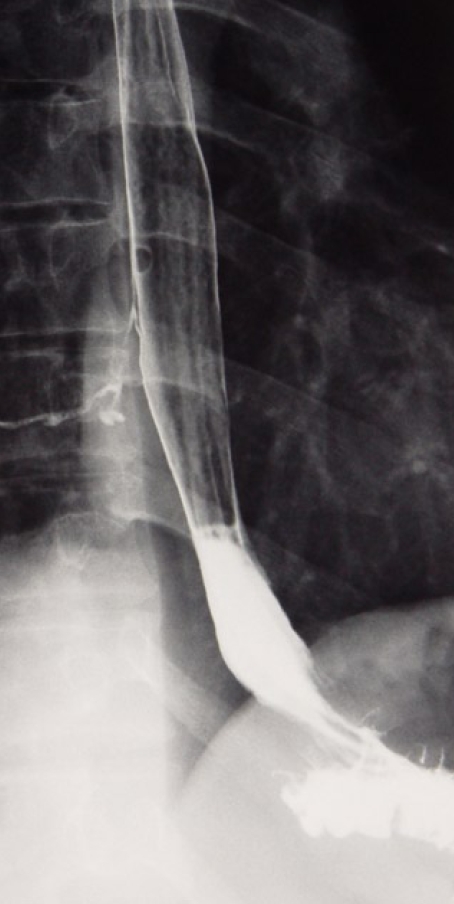

We decided on a non-surgical therapeutic endoscopic procedure. During upper gastrointestinal endoscopy performed by one of us (E.V.T), a sclerotherapy catheter was inserted through which 1 mL of ready to use synthetic surgical glue (Glubran 2, GEM Srl, Viareggio Italy) closed the fistula opening with excellent results (Figures 4A and B). The patient is completely asymptomatic at 6 mo follow up.

Figure 4.

Gastrograffin follow through 1 mo after endoscopic therapy of esophago-bronchial fistula with glue.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge this is the first case of esophago-broncheal fistula due to HGM in the esophagus and the second case ever reported on esophageal fistula related to HGM. The other case reported on a 50-year-old male patient with a fine fistula between the esophagus and the trachea located near the upper thoracic aperture. In that case[12] the only item worthy of note was diagnosis of lung tuberculosis followed by a fistula diagnosis four years later.

It is noteworthy that the fistula and HGM diagnosis in our patient was possible after a very prolonged period of atypical lower respiratory tract symptoms. In fact, HGM patches have been associated with a broad spectrum of symptoms such as ulceration, bleeding, perforation and malignant transformations[2]. If asymptomatic the clinical importance of esophageal HGM patches is debatable[5].

The asymptomatic nature of these HGM patches, simple oversight and sometimes technical difficulty can mean that endoscopists are unfamiliar with these lesions. The characteristic ‘salmon-colored’ appearance of the HGM patch, not evident in the fistula opening of our case, can confirm diagnosis using Congo red dye application (1% in distilled water) to the suspected area; according to the authors[9] after 5 min small punctuate areas within the patch turn from red to black, confirming a fall in pH and that this patch is acid-producing. Although pertechnetate scintigraphy (Tc-99m) has been suggested[17] in order to confirm HGM diagnosis and to localise other possible patches, it proved of no help in our case.

Our patient had a small gastro-esophageal hernia and no evidence of concomitant Barrett’s esophagus. Traditionally, esophageal HGM is considered a distinct entity from Barrett’s esophagus. The presence of specialized columnar epithelium characterized by acid mucin-containing goblet cells has been accepted as diagnostic of Barrett’s esophagus. The American College of Gastroenterology and its Practice Parameters Committee provided a definition of Barrett’s esophagus as a change in the esophageal epithelium of any length that can be recognized at endoscopy and is confirmed by biopsy to have intestinal metaplasia[18]. A healing process of the lower esophagus in response to injury from gastric reflux is believed to be its primary etiology[7-12].

The presence of an esophageal HGM patch has been associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease[8]. Of interest, immunohistological studies suggested a similarity between Barrett epithelium and HGM patch[18-19]. These studies have shown that Barrett epithelium and HGM have the same mucin core protein expression and cytokeratin pattern (cytokeratins 7 and 20)[19], thus suggesting a pathogenetic link between these two diseases. However, in the study of Borhan-Manesh et al[5], the incidence of esophagitis and Barrett’s epithelium in a population of 64 veterans with endoscopically found HGM patches did not significantly differ from that observed in 570 patients without these patches. On the other hand, it is possible that occasional cases of Barrett's mucosa at the distal end of the esophagus are nothing but the failure of the squamous epithelium to carpet the area resulting in Barrett’s epithelium. However, the 10 cm distance of HGM from the gastro-esophageal junction and the absence of concomitant Barrett’s lesions exclude this probability in our patient. Furthermore, histological changes of the squamous epithelium distally adjacent to the HGM area in our patient did not show changes consistent with reflux esophagitis.

Despite the fact that the HGM patch in this patient was Helicobacter pylori negative, we cannot exclude the probability that Helicobacter pylori causing chronic gastritis in our patient may also have previously colonized the HGM patch contributing to ulcerogenesis and subsequent fistula formation[20-22].

In our patient, as HGM was obviously related to recurrent respiratory symptoms, fistula closure was the only definite therapy. We decided to treat our patient using a technique similar to that applied in the previous fistula case. In that case[12], a two-step endoscopic therapy was made to close off the esophagotracheal fistula with the aid of the same type of glue we also used. The adhesive was selectively applied into the fistula track via a 1.5m long irrigation catheter passing down the biopsy channel of the endoscope. Four days later, a further 2 mL of fibrin adhesive was selectively instilled into the fistula opening.

Treatment of symptomatic HGM is necessary in order to relieve symptoms and to further prevent the development of other complications. Efficient treatment can be successfully offered with the use of proton pump inhibitors. If appropriate and when medical therapy fails to promote regression of symptoms, transcervical or endoscopic biopsy and/or excision are warranted[1]. Endoscopic laser ablation is an acceptable treatment modality because of the rarity of malignant transformation. However, if a small focus of malignancy is suspected, complete local excision with narrow margins is the treatment of choice in order to exclude further progression[23]. Mucosectomy of the patch aided with chromoendoscopy with 0.5% methylene blue has been also suggested[4] and long-term follow up of these patients seems of great importance.

The criteria for gluing are defined on an individual basis and parallel the experience of every physician in such a method. In general, small in size and length, well-defined, non-inflamed fistula with no concomitant regional abscess can be treated with glue.

In conclusion, we presented herein an exceptional case of symptomatic esophageal gastric heterotopia with esophago-bronchial fistula formation. We have discussed pathophysiological and diagnostic issues and have described the endoscopic therapy which should be the treatment of first choice in such cases.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: David Friedel, MD, Gastroenterology, Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, NY 11501, United States; Naoki Muguruma, MD, PhD, Department of Gastroenterology and Oncology, The University of Tokushima Graduate School, Kuramoto-cho, Tokushima 770-8503, Japan

S- Editor Zhang HN L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Liu N

References

- 1.Ishoo E, Busaba NY. Ectopic gastric mucosa in the cervical esophagus. Am J Otolaryngol. 2002;23:181–184. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2002.123437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chong VH, Jalihal A. Cervical inlet patch: case series and literature review. South Med J. 2006;99:865–869. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000231246.28273.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wetmore RF, Bartlett SP, Papsin B, Todd NW. Heterotopic gastric mucosa of the oral cavity: a rare entity. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;66:139–142. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(02)00236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Angelis P, Trecca A, Francalanci P, Torroni F, Federici Di Abriola G, Papadatou B, Ciofetta GC, Dall’Oglio L. Heterotopic gastric mucosa of the rectum. Endoscopy. 2004;36:927. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borhan-Manesh F, Farnum JB. Incidence of heterotopic gastric mucosa in the upper oesophagus. Gut. 1991;32:968–972. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.9.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takubo K, Aida J, Sawabe M, Arai T, Kato H, Pech O, Arima M. The normal anatomy around the oesophagogastric junction: a histopathologic view and its correlation with endoscopy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:569–583. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lessells AM, Martin DF. Heterotopic gastric mucosa in the duodenum. J Clin Pathol. 1982;35:591–595. doi: 10.1136/jcp.35.6.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sánchez-Pernaute A, Hernando F, Díez-Valladares L, González O, Pérez Aguirre E, Furió V, Remezal M, Torres A, Balibrea JL. Heterotopic gastric mucosa in the upper esophagus (“inlet patch”): a rare cause of esophageal perforation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3047–3050. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrne M, Sheehan K, Kay E, Patchett S. Symptomatic ulceration of an acid-producing oesophageal inlet patch colonized by helicobacter pylori. Endoscopy. 2002;34:514. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bataller R, Bordas JM, Ordi J, Llach J, Elizalde JI, Mondelo F. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a complication of “inlet patch mucosa” in the upper esophagus. Endoscopy. 1995;27:282. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steadman C, Kerlin P, Teague C, Stephenson P. High esophageal stricture: a complication of “inlet patch” mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:521–524. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohler B, Köhler G, Riemann JF. Spontaneous esophagotracheal fistula resulting from ulcer in heterotopic gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:828–830. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weaver GA. Upper esophageal web due to a ring formed by a squamocolumnar junction with ectopic gastric mucosa (another explanation of the Paterson-Kelly, Plummer-Vinson syndrome) Dig Dis Sci. 1979;24:959–963. doi: 10.1007/BF01311954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CARRIE A. Adenocarcinoma of the upper end of the oesophagus arising from ectopic gastric epithelium. Br J Surg. 1950;37:474. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18003714810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takagi A, Ema Y, Horii S, Morishita M, Miyaishi O, Kino I. Early adenocarcinoma arising from ectopic gastric mucosa in the cervical esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:167–170. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)80605-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spiller RC, Shousha S, Barrison IG. Heterotopic gastric tissue in the duodenum: a report of eight cases. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27:880–883. doi: 10.1007/BF01316570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emamian SA, Shalaby-Rana E, Majd M. The spectrum of heterotopic gastric mucosa in children detected by Tc-99m pertechnetate scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 2001;26:529–535. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200106000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sampliner RE. Practice guidelines on the diagnosis, surveillance, and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1028–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lauwers GY, Mino M, Ban S, Forcione D, Eatherton DE, Shimizu M, Sevestre H. Cytokeratins 7 and 20 and mucin core protein expression in esophageal cervical inlet patch. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:437–442. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000155155.46434.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamilton JW, Thune RG, Morrissey JF. Symptomatic ectopic gastric epithelium of the cervical esophagus. Demonstration of acid production with Congo red. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:337–342. doi: 10.1007/BF01311666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jabbari M, Goresky CA, Lough J, Yaffe C, Daly D, Côté C. The inlet patch: heterotopic gastric mucosa in the upper esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:352–356. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrick J, Lee A, Hazell S, Ralston M, Daskalopoulos G. Campylobacter pylori, duodenal ulcer, and gastric metaplasia: possible role of functional heterotopic tissue in ulcerogenesis. Gut. 1989;30:790–797. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.6.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abe T, Hosokawa M, Kusumi T, Kusano M, Hokari K, Kagaya H, Watanabe A, Fujita M, Sasaki S. Adenocarcinoma arising from ectopic gastric mucosa in the cervical esophagus. Am J Clin Oncol. 2004;27:644–645. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000147808.63442.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]