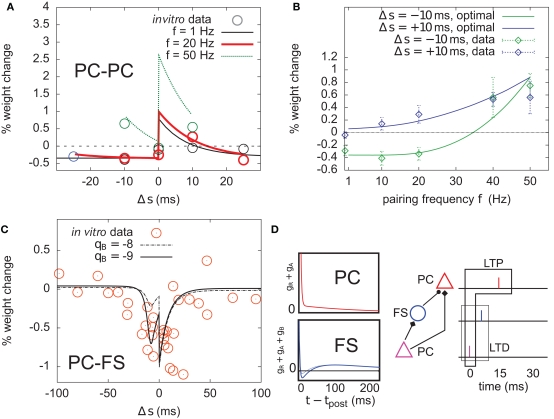

Figure 8.

Optimal plasticity shares features with target-cell specific STDP. (A) The optimal model applied on 60 pre–post pairs repeating at 1 (black line), 20 (red thick), and 50 Hz (green) yields STDP learning windows that qualitatively match those recorded in Sjöström et al. (2001). For comparison, the in vitro data has been redrawn with permission. (B) LTP dominates when the pairing frequency is increased. The optimal frequency window is plotted for post-before-pre (−10 ms, solid green curve) and pre-before-post pairs (+10 ms, solid blue) repeated with frequency f (x-axis). Points and error bars are the experimental data, redrawn from Sjöström et al. (2001) with permission. (C) Learning window that minimizes information transmission at an excitatory synapse onto a fast-spiking (FS) inhibitory interneuron. The procedure is the same as in (A). The spike-triggered adaptation kernel was updated to better match that of a FS cell (see D). Dots are redrawn from Lu et al. (2007). (D) Left: after-spike kernels of firing rate suppression for the principal excitatory cell (red, same as the one we used throughout the article, see Materials and Methods) and the fast-spiking interneuron (blue). The latter was modeled by adding a third variable qB < 0 with time constant τB = 30 ms to the initial kernel. Solid blue line: qB = −9. Dashed blue line: qB = −8. Right: schematic of a feed-forward inhibition microcircuit. A first principal cell (PC) makes an excitatory connection to another PC. It also inhibits it indirectly through a FS interneuron. The example spike trains illustrate the benefit of having LTD for pre-before-post pairing at the PC–FS synapse (see text).