Abstract

Evidence suggests that dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) plays a key role in stress and coping responses. Fecal sampling permits assessment of hormone-behavior interactions reliably and effectively, but no previous study has compared circadian- or stress-dependent alterations between serum DHEA and its fecal metabolites. In the current study, young (28 d of age) male rats were assigned to either an experimental (n = 6) or control (n = 6) group. Rats in the experimental group were exposed to a forced swim test to assess their behavioral and physiologic response to an environmental stressor; blood samples were drawn before the test (baseline), immediately after the test, and at 2 later time points. Only fecal samples were collected from control animals. Fecal DHEA and corticosterone metabolites were monitored in all animals for 24 h. DHEA metabolites in control rats exhibited significant diurnal variation, showing a similar temporal pattern as that of corticosterone metabolites. In addition, fecal and serum DHEA levels were highly correlated. Significant peaks in both DHEA and corticosterone metabolite levels were detected. These data suggest that measures of fecal DHEA can provide a complementary, noninvasive method of assessing adrenal gland function in rats.

Abbreviation: DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone

Effective coping strategies likely evolved to provide neurobiologic adaptations to situations that threatened an animal's survival.12,23,44 Coping styles influence an animal's adaptive functions and subsequent susceptibility to stress-related disease.21,22 Hormonal responses, such as glucocorticoid and epinephrine secretion, represent the front-line responses to stressors in most mammals, including the laboratory rat.14,20,25 Consequently, corticosterone and cortisol frequently are selected as representative indicators of the physiologic stress response of animals.7,38 Little research regarding dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and stress is available, although evidence exists indicating that this hormone plays a critical role in the stress response and coping mechanisms.9 DHEA and its sulfate ester are the major circulating products of adrenal glands; in addition, 20% of circulating DHEA is produced by ovarian theca cells under the control of luteinizing hormone and by the central nervous system, as indicated by data obtained from ovariectomized and adrenalectomized rats.11,35 DHEA has been shown to be released parallel to cortisol during physical stress9,18 to protect the body against the negative effects of prolonged exposure to glucocorticoids.32 Research has demonstrated that DHEA can act centrally to decrease glucocorticoid-induced neuronal death in the hippocampus28 and to promote neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus and in sensory dorsal root ganglion neurons.36,43 In humans, increased levels of DHEA have been correlated with reduced mental illness symptomology and better task performance in patients suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder37 and improved spatial navigation in an underwater scuba diving task.32 Furthermore, the ratio between DHEA and cortisol has been found to be a reliable index of neuroprotection (for review, see reference 27). Therefore, research elucidating the nature of effective coping strategies demonstrated by various species is necessary for enhanced understanding of the many complex aspects of stress responses. Furthermore, including measures of DHEA levels in studies of laboratory animals focused on the stress response would be beneficial.27

Although serum samples have frequently been used in several species, obtaining blood samples at sufficient intervals to examine endocrine variability to modifications in behavior often presents methodologic and ethical challenges.4,30 For example, invasive techniques such as cardiac puncture, venipuncture, and tail clipping often are conducted to collect blood from numerous sources, including the retroorbital sinus, jugular vein, maxillary vein, saphenous vein, and heart. Each technique has its advantages and disadvantages.2 In addition to methodologic challenges, some of these techniques are no longer approved by institutional animal care committees in some countries (for example, retroorbital collection is no longer permitted in Holland).6 In addition, peripheral serum concentrations in blood samples are not always an accurate indicator of chronic stress situations; for example, high plasma concentrations of glucocorticoids inhibit the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone from the pituitary gland, which in turn decreases hormone secretion by the adrenal cortex, thereby generating a pulsatile pattern of secretion.26 Therefore, high concentrations of plasma glucocorticoids due to acute stressors do not usually persist for a long time.29

In contrast to blood, the collection of excreta samples (urine or feces) allows the monitoring of previous stressful conditions, without the additional potential stressors of restraining or anesthetizing the animals. Although serum collection has advantages in certain acute stress scenarios, steroid levels in excreta provide a type of cumulative endocrine profile as several hours' worth of previous endocrine and metabolic activation are assessed. Therefore, in some cases, fecal sampling may provide a more thorough and accurate indicator of an animal's overall endocrine state than do the ‘snapshot’ serum levels of rapidly fluctuating hormones.41,45

Validation of simple methods for extraction and quantification of several steroid hormones, including glucocorticoids (such as cortisol and corticosterone) and sex steroids, has been provided in previous studies focused on several rodent species;1,3,15,24,39,42 however, none of these previous studies have explored putative similarities between peripheral secretion of DHEA and the concentration of metabolized DHEA in fecal samples. Accordingly, the purpose of the present study was to test a method for the quantification of DHEA metabolites in the feces of young male laboratory rats. We used an experimental paradigm to validate paired plasma and hormone metabolite profiles from both control (no stress) and experimental (participated in a forced swim stress test) rats and to document the validity of the technique for stress-induced endocrine assessment. In addition, a parametric analysis of fecal and plasma DHEA diurnal response profiles was conducted to further examine the effectiveness of using fecal samples for noninvasive assessment of DHEA in laboratory rats. On the bases of previous studies,27,31,39 we hypothesized that animals exposed to acute stress would respond with elevated levels of both corticosterone and DHEA in plasma and, after a delay due to metabolic events, a peak in fecal DHEA and corticosterone metabolites would be detectable.

Materials and Methods

Subjects.

Male Long Evans rats (age, 21 d; n = 12) were purchased from Sprague–Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). On arrival at the laboratory, the rats were housed in groups of 3 in cages (48 cm × 26 cm × 21 cm) to acclimate to laboratory conditions prior to the beginning of the experiment. Rats subsequently were assigned to an experimental (n = 6) or control (n = 6) group. To differentiate rats in each group, a color code was placed on their tails with a permanent marker. Each rat in the experimental group participated in a 5-min forced swim test in a glass aquarium (60 × 31 × 53 cm; water was approximately 30 cm deep and was maintained at room temperature) just before blood was collected for the second time. All cages were lined with Kay-Kob bedding (Kaytee Products, Chilton, WI); rats were given food (Mazuri Rodent Chow, Purina Mills, St Louis, MO) and water ad libitum throughout the study. A 12:12-h light:dark cycle began with lights on at 0600. Ambient temperature was maintained at 24 °C. All animals were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of Randolph–Macon College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and all procedures were in compliance with guidelines in the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.17

Blood sample collection.

At 28 d of age, after 1 wk of habituation, blood sampling in the experimental group commenced on day 1 at 1800 and was repeated at 2000 h, 2200 h, and on day 2 at 0600 h. Blood collection started at the time of awakening for the rats, therefore glucocorticoids were at their expected circadian peak. The other times were selected as a compromise between giving enough time to the rats to rest after the sampling and the need to have continuous data collection. Blood samples were taken from the submandibular vein, a vascular bundle located at the rear of the jaw bone, providing an effective and consistent source of blood. For the puncture, sterile lancets (Goldenrod Animal Lancets; point length, 6.5 mm; MediPoint, Mineola, NY) were used. The 6.5-mm length was sufficient for young rats. Before venipuncture, the rats were anesthetized by exposing them to 0.5 mL halothane (Sigma Aldrich; St Louis, MO) while inside a small container. The rats then were retrieved as shown on the MediPoint website (www.medipoint.com); subsequently the correct position at the rear of the jaw was located by using the back of the lancet and the vein accessed. When necessary, bleeding was stopped by using a cotton tip. By using this technique, as much 1 mL blood was collected from most of the rats; overall 18 of the 24 planned samples were obtained. The entire process, including anesthetization, was fairly quick, with the total collection time averaging approximately 165 s. The rats were monitored throughout the procedure and recovered quickly. Only one animal developed visible swelling on the neck; the swelling disappeared after 1 d.

Blood samples were collected into 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tubes (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) treated with EDTA as an anticoagulant. The samples were stored at 4 °C, centrifuged (1500 × g for 10 min) for serum separation, and then stored at −70 °C until analysis.

Collection and extraction of fecal samples.

Fresh uncontaminated fecal samples were collected from both experimental and control subjects (n = 12). At the scheduled time of collection, the rats were placed individually in a cage designated for fecal sample collections for a few minutes until defecation was observed. Only samples collected within 15 min of the scheduled time were used in the assay. Fecal samples from the experimental group were collected just after blood collection, when rats were caged individually to rest for about 15 min before being reintroduced to their home cages. Samples were collected from each animal and homogenized; 0.1 g fresh feces was obtained for each animal and frozen in sealed containers at −70 °C until analysis. Fecal sample collection started on day 1 at 1800 and continued until the day after for a total of 8 samples per rat, collected at 2, 4, 12, 14, 16, 18, and 24 h after stress exposure in the experimental animals. Overall, 88 of the 96 fecal samples planned were collected.

Prior to extraction, previously collected fecal samples were thawed at room temperature and placed in a glass tube with 1 mL 100% methanol. The contents of the tube were vortexed for approximately 30 s and centrifuged for 10 min at 1500 × g. By using a transfer pipette, the sample was transferred to a 13 × 100-mm glass test tube. The methanolic extract of each fecal sample was diluted 1:20 with the buffer supplied with the immunoassay kits.

Enzyme immunoassay.

Assay procedures were carried by out using materials and protocols provided with an enzyme immunoassay kit (Corticosterone Enzyme Immunoassay Kit, catalog no. 900-097, and DHEA Enzyme Immunoassay Kit, catalog no. 900-093; Assay Designs, Anne Arbor, MI). Samples were analyzed in duplicate. The crossreactivity of the DHEA kit was 100% with DHEA, 30% with DHEA sulfate, and less than 1% with androstenedione and androsterone). The crossreactivity of the corticosterone kit was 100% with corticosterone, 8.6% with deoxycorticosterone, and less than 1% with other steroids. Dose response of the assays, assessed by spiking sample extracts with a known amount of DHEA and corticosterone standard in increasing amounts, generated a curve with an average slope of 0.96 and a correlation coefficient of 0.98. Quality-control samples (pools) were run during the assays, and the intraassay precision of our samples was in the range of the kit standards (average coefficient of variation: 6.1% for corticosterone; 11.4% for DHEA). The average interassay coefficient of variation (calculated by repeating 3 different quality-control samples) was 15% for DHEA and 12% for corticosterone.

Samples were evaluated at a wavelength of 405λ on an automated microplate reader (model no. EL x 800, BioTek, Winooski, VT) with the Kcjunior software (catalog no. 5270501, BioTek).

Statistical analysis.

Patterns of changes of corticosterone and DHEA trends in both serum and fecal samples were analyzed by using repeated-measures ANOVA, with factors of hormones recovery, medium (serum × feces), and time (4 points for serum, 8 points for feces). Correlation between hormones levels in both media were analyzed by using Pearson correlation. Values for missing samples were extrapolated by using linear interporlation at point of analysis, thereby increasing the reliability of the statistical tests. The significance of the peaks observed in serum and fecal samples were analyzed by using Newman–Keuls post hoc tests. All analyses were 2-tailed. Data were analyzed by using the software package SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Diurnal variations.

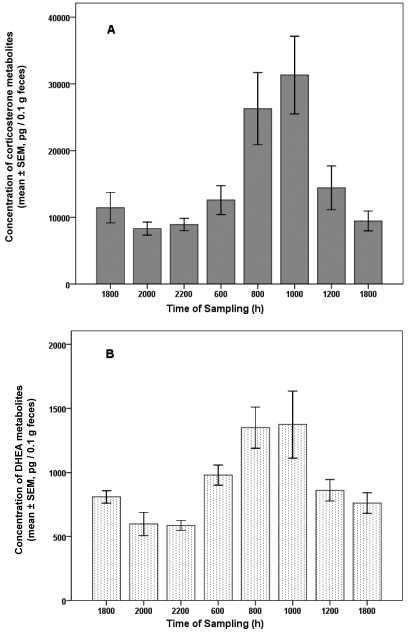

We found significant diurnal variation in excreted fecal corticosterone and DHEA metabolites in the control rats (F[7,35] = 7.96, P < 0.001 and F[7,35] = 6.27, P < 0.001, respectively). The patterns of variation between fecal corticosterone and DHEA metabolite levels were parallel and did not differ significantly (F[7,77] = 1.2, P = 0.33; Figure 1). In addition, the correlation between levels of excreted corticosterone and DHEA was significant (r = 0.37, P < 0.01). The highest values for both metabolites occurred in the morning between 0800 and 1200.

Figure 1.

Diurnal variation of fecal profile of immunoreactive (A) corticosterone metabolites and (B) DHEA metabolites in the feces of young rats (n = 6).

Stress test.

The experimental group of rats demonstrated a significant peak in the concentration of serum DHEA immediately after the stress test (F[3,15] = 8.7, P = 0.01; Figure 2). Further, significant peaks for both corticosterone and DHEA metabolites were offset by 14 ± 6 h (F[7,35] = 5.27, P < 0.001 and F[7,35] = 613.1, P < 0.001, respectively; Figure 3). In addition, the patterns of variation in the levels of both metabolites paralleled each other after the stress test and did not differ significantly (F[7,77] = 0.9, P = 0.67). The correlation between plasma levels of DHEA and its metabolites was significant (r = 0.69, P < 0.01), as was that between the amounts of corticosterone and its metabolites in plasma (r = 0.42, P < 0.05). In addition, the correlation between the levels of the 2 metabolites was significant (r = 0.41, P < 0.01). After the stress test, fecal corticosterone and DHEA metabolites were significantly higher in the experimental (stress) group compared with the appropriate control groups (F[1,10] = 26.7, P < 0.01 and F[1,10] = 12.9, P < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Concentrations of (A) Serum corticosterone at baseline (time, 1800), after the stress test (forced swim, indicated by arrow at time 2000), and after recovery at 2 and 10 h after the stress test in young adult rats (n = 6). (B) Serum DHEA levels at baseline (time, 1800), after the stress test (forced swim, indicated by arrow at time 2000 h), and after recovery at 2 and 10 h after the stress test in young adult rats (n = 6).

Figure 3.

Concentrations of immunoreactive (A) corticosterone metabolites and (B) DHEA metabolites in the feces of young rats (n = 6) after a stress test (indicated by arrow at time 2000). Diurnal variation calculated on the basis of the P values of the control group (n = 6) is indicated as a line.

Discussion

The establishment of accurate and reliable parameters of hormonal analysis in excreta may render obsolete the invasive procedure of collecting chronic blood samples. For studying endocrine activation, fecal samples offer a better, noninvasive technique, particularly when the focus of the research is behavioral assessment.1,13,42 Although previous studies have performed validations of fecal glucocorticoid metabolites in several rodent species,8,24,39 no previous study had assessed the validity of fecal DHEA immunoreactivity in laboratory rats. The present study complements the existing literature by providing data on the validation of a simple method to assess DHEA metabolites levels in the feces of young male rats, although the same technique presumably can be used in adult rats as well, as was done in our laboratory studying chronic and acute stress in rats.16 Given the relevance of DHEA in the study of stress and coping mechanisms,27,28,36,43 a physiologic validation of extraction and assay of DHEA metabolites from fecal samples has considerable potential in the study of behavioral and physiologic responses to acute and chronic challenges in rodents.

Measurements of DHEA metabolites in the feces of undisturbed control young male rats produced profiles significantly correlated with corticosterone metabolites, including significant diurnal variation, as expected from previous studies.11,35 Because glucocorticoids are heavily metabolized prior to excretion, performing HPLC to provide further verification that the steroid measures in plasma were indeed DHEA would be informative. However, considering that the assay kit was selected to minimize crossreactivity with other metabolites, these findings are an important first step that suggests that DHEA can be assessed in fecal samples. Our findings also confirmed that the observed trends and hourly values were in the expected range of variation.3,10 Animals in the experimental group, which underwent a forced swim test, showed a significant increase of circulating DHEA levels immediately after the test as well as several peaks in both metabolized DHEA and corticosterone levels that were offset by approximately 14 h; these findings are in agreement with previous studies on fecal glucocorticoid metabolites.24 The baseline levels of both hormones did not differ significantly from those of the control group. These results support the hypothesis that DHEA metabolites can be detected in rats undergoing acute stress. Due to the time-frame of the present design, we were not able to calculate the exact time needed for DHEA metabolite levels to return to baseline, although a trend for recovery was offset by at least 18 h. The similar response profiles of excreted DHEA and corticosterone also supported the hypothesis that DHEA can be measured reliably in fecal samples of young male rats.

Several limitations of the present research need to be addressed in the future. To minimize stress in the control group, blood was not collected from these rats. In addition, the addition of a secondary control group, which would have undergone blood collection but not to the stress test, would further elucidate the roles of circadian rhythms and stress exposure in corticosterone and DHEA excretion patterns. Nevertheless, in the current study, synchronized blood and fecal metabolite peaks confirmed the value of fecal collection techniques. The inclusion of female rats in the current study would have provided a more complete picture of these hormonal secretions. Although previous studies validating fecal glucorticoid metabolites in rodents were able to detect similar diurnal variations in both male and female animals, some differences between the 2 sexes have been observed.33,42 Consequently, a similar study involving female rats is required for a full understanding of the DHEA endocrine response profile. In addition, even though age has been determined to be an important variable in some studies,5 recent data have indicated that there is no difference in fecal corticosterone metabolites in spiny mice of different ages.33 Even so, it would be interesting to examine developmental effects of the DHEA response in future studies. Further, although groups of 6 to 8 subjects are not uncommon when using laboratory rats, clearly the range of interindividual variation for both circulating and excreted hormones makes it difficult to obtain significant and accurate calculations when small samples (6 or fewer subjects) are used. Finally, it would be extremely beneficial to extend data collection for at least 48 h, including blood collection for at least 24 h, with less frequent collection to avoid damage or loss of animals in the process. This extension would enable the detection of secondary peaks, making calculation of both recovery time and offset timing between serum and metabolized levels more accurate and reliable. Although the current research focused on behavior-induced neuroendocrine activation and although the forced swim test has been reliably used as an acceptable paradigm for acute stress in previous research,31 it would be informative to perform pharmacologic stimulation and suppression of adrenocortical activity in a secondary experimental group, as done in several previous studies assessing corticosterone metabolites.24,42

In conclusion, the current results suggest that fecal DHEA metabolites can be measured in young male rats. Given the importance of the inclusion of DHEA in the study of stress and coping mechanisms27,28,40 and lack of a published account that examines the relationship between fecal DHEA and serum DHEA, our data offer a meaningful complement to the existing corticosterone research literature. Moreover, laboratory rats rank as one of the most studied laboratory animals, and the establishment of valid techniques to assess circulating DHEA levels as a stress or coping marker likely will contribute to further research investigating the stress response.19,34 Further studies are needed to resolve the problem of crossreactivity of testosterone metabolites in adult male rats, which could confound the measurements. The use of HPLC to confirm the nature of the metabolites reacting with the antibodies in the assay kit would be also informative. Additional analyses of both corticosterone and DHEA levels in laboratory studies of animals exposed to various forms of stress and exhibiting varying degrees of resilience would be beneficial as well.16,27

Collecting fecal samples in rats is simple and cost-effective in comparison with even the most convenient and refined blood collection techniques; this benefit is important because, when focusing on behavioral research, it is imperative to avoid invasive techniques.16 In sum, analysis of fecal samples allows for regular, noninvasive sampling of subjects, permitting reliable and effective assessment of DHEA–behavior interactions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Stephanie Wemm and Alexandra Rhone for their assistance during data collection. We also recognize and thank Randolph–Macon College for its continuing and generous support of our research. This research funded in part by the Macon and Joan Brock Professorship in Psychology.

References

- 1.Abelson KS, Fard SS, Nyman J, Goldkuhl R, Hau J. 2009. Distribution of [3H]-corticosterone in urine, feces, and blood of male Sprague–Dawley rats after tail vein and jugular vein injections. In Vivo 23:381–386 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angelov O, Schroer RA, Heft S, James VC, Noble J. 1984. A comparison of 2 methods of bleeding rats: the venous plexus of the eye versus the vena sublingualis. J Appl Toxicol 4:258–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bamberg E, Palme R, Meingassner JG. 2001. Excretion of corticosteroid metabolites in urine and faeces of rats. Lab Anim 35:307–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett GM, Shimizu K, Bardi M, Mori A. 2002. Fecal testosterone immunoreactivity as a noninvasive index of functional testosterone dynamics in male Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata). Primates 43:29–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer ME. 2008. Chronic stress and immunosenescence: a review. Neuroimmunomodulation 15:241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beeton C, Garcia A, Chandy G. 2007. Drawing blood from rats through the saphenus vein and by cardiac puncture. J Vis Exp (7):266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boccia ML, Laudenslager ML, Reite ML. 1995. Individual differences in macaques' responses to stressors based on social and physiological factors: implications for primate welfare and research outcomes. Lab Anim 29:250–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosson CO, Palme R, Boonstra R. 2009. Assessment of the stress response in Columbian ground squirrels: laboratory and field validation of an enzyme immunoassay for fecal cortisol metabolites. Physiol Biochem Zool 82:291–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charney DS. 2004. Psychobiological mechanisms of resilience and vulnerability: implications for successful adaptation to extreme stress. Am J Psychiatr 161:195–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen H, Maayan R, Touati-Werner D, Kaplan Z, Matar MA, Loewenthal U, Kozlovsky N, Weizman R. 2007. Decreased circulatory levels of neuroactive steroids in behaviourally more extremely affected rats subsequent to exposure to a potentially traumatic experience. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 10:203–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corpechot C, Robert P, Axelson M, Sjovall J, Baulieu EE. 1981. Characterization and measurement of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in the rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 78:4704–4707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darnaudéry M, Maccari S. 2008. Epigenetic programming of the stress response in male and female rats by prenatal restraint stress. Brain Res Rev 57:571–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dehnhard M, Naidenko S, Frank A, Braun B, Göritz F, Jewgenow K. 2008. Noninvasive monitoring of hormones: a tool to improve reproduction in captive breeding of the Eurasian lynx. Reprod Domest Anim 43 Suppl 2:74–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domingues Santos C, Loria RM, Rodrigues Oliveira LG, Collins Kuehn C, Alonso Toldo MP, Albuquerque S, do Prado Júnior JC. 2010. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) and benznidazole treatments during acute infection of 2 different Trypanosoma cruzi strains. Immunobiology 215:980–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eriksson E, Royo F, Lyberg K, Carlsson HE, Hau J. 2004. Effect of metabolic cage housing on immunoglobulin A and corticosterone excretion in faeces and urine of young male rats. Exp Physiol 89:427–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawley DF, Bardi M, Everette AM, Higgins TJ, Tu KM, Kinsley CH, Lambert KG. 2010. Neurobiological constituents of active, passive and variable coping strategies in male Long–Evans rats. Stress 13:172–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research 1996. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izawa S, Sugaya N, Shirotsuki K, Yamada KC, Ogawa N, Ouchi Y, Nagano Y, Suzuki K, Nomura S. 2008. Salivary dehydroepiandrosterone secretion in response to acute psychosocial stress and its correlations with biological and psychological changes. Biol Psychol 79:294–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacob MH, Janner Dda R, Belló-Klein A, Llesuy SF, Ribeiro MF. 2008. Dehydroepiandrosterone modulates antioxidant enzymes and Akt signaling in healthy Wistar rat hearts. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 112:138–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jezova D, Hlavacova N. 2008. Endocrine factors in stress and psychiatric disorders: focus on anxiety and salivary steroids. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1148:495–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koolhaas JM, de Boer SF, Buwalda B, van Reenen K. 2007. Individual variation in coping with stress: a multidimensional approach of ultimate and proximate mechanisms. Brain Behav Evol 70:218–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koolhaas JM, Korte SM, DeBoer SF, Van Der Begt BJ, Van Reenen CG, Hopsger H, De Jong IC, Ruis MAW, Blokhuis HJ. 1999. Coping styles in animals: current status in behavior and stress physiology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 23:925–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lambert KG. 2006. Rising rates of depression in today's society: consideration of the roles of effort-based rewards and enhanced resilience in day-to-day functioning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 30:497–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lepschy M, Touma C, Hruby R, Palme R. 2007. Noninvasive measurement of adrenocortical activity in male and female rats. Lab Anim 41:372–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lightman SL. 2008. The neuroendocrinology of stress: a never-ending story. J Neuroendocrinol 20:880–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lightman SL, Wiles CC, Atkinson HC, Henley DE, Russell GM, Leendertz JA, McKenna MA, Spiga F, Wood SA, Conway-Campbell BL. 2008. The significance of glucocorticoid pulsatility. Eur J Pharmacol 583:255–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maninger N, Capitanio JP, Mason WA, Ruys JD, Mendoza SP. 2010. Acute and chronic stress increase DHEAS concentrations in rhesus monkeys. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35:1055–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maninger N, Wolkowitz OM, Reus VI, Epel ES, Mellon SH. 2009. Neurobiological and neuropsychiatric effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate (DHEAS). Front Neuroendocrinol 30:65–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manser C. 1992. The assessment of stress in laboratory animals. Causeway (UK): Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mateo JM, Cavigelli SA. 2005. A validation of extraction methods for noninvasive sampling of glucocorticoids in free-living ground squirrels. Physiol Biochem Zool 78:1069–1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathews IZ, Wilton A, Styles A, McCormick CM. 2008. Increased depressive behaviour in females and heightened corticosterone release in males to swim stress after adolescent social stress in rats. Behav Brain Res 190:33–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan CA 3rd, Rasmusson A, Pietrzak RH, Coric V, Southwick SM. 2009. Relationships among plasma dehydroepiandrosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, cortisol, symptoms of dissociation, and objective performance in humans exposed to underwater navigation stress. Biol Psychiatry 66:334–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nováková M, Palme R, Kutalová H, Janský L, Frynta D. 2008. The effects of sex, age, and commensal way of life on levels of fecal glucocorticoid metabolites in spiny mice (Acomys cahirinus). Physiol Behav 95:187–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obut TA, Ovsyukova MV, Dement'eva TY, Cherkasova OP, Saryg SK, Grigor'eva TA. 2009. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate on the conversion of corticosterone into 11-dehydrocorticosterone in stress: a regulatory scheme. Neurosci Behav Physiol 39:695–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parker LN, Odell WD. 1980. Control of adrenal androgen secretion. Endocr Rev 4:392–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinnock SB, Lazic SE, Wong HT, Wong IH, Herbert J. 2009. Synergistic effects of dehydroepiandrosterone and fluoxetine on proliferation of progenitor cells in the dentate gyrus of the adult male rat. Neuroscience 158:1644–1651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rasmusson AM, Vasek J, Lipschitz DS, Volvoda D, Mustone ME, Shi Q, Gudmundsen G, Morgan CA, Wolfe J, Charney DS. 2004. An increased capacity for adrenal DHEA release is associated with decreased avoidance and negative mood symptoms in women with PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology 29:1546–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sapolsky RM. 2000. Glucocorticoids and hippocampal atrophy in neuropsychiatric disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatr 57:925–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siswanto H, Hau J, Carlsson HE, Goldkuhl R, Abelson KS. 2008. Corticosterone concentrations in blood and excretion in faeces after ACTH administration in male Sprague–Dawley rats. In Vivo 22:435–440 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song L, Tang X, Kong Y, Ma H, Zou S. 2010. The expression of serum steroid sex hormones and steroidogenic enzymes following intraperitoneal administration of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in male rats. Steroids 75:213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strier KB, Ziegler TE. 2005. Advances in field-based studies of primate behavioral endocrinology. Am J Primatol 67:1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Touma C, Palme R, Sachser N. 2004. Analyzing corticosterone metabolites in fecal samples of mice: a noninvasive technique to monitor stress hormones. Horm Behav 45:10–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ulmann L, Rodeau JL, Danoux L, Contet-Audonneau JL, Pauly G, Schlichter R. 2009. Dehydroepiandrosterone and neurotrophins favor axonal growth in a sensory neuron–keratinocyte coculture model. Neuroscience 159:514–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wechsler B. 1995. Coping and coping strategies: a behavioural view. Appl Anim Behav Sci 43:123–134 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whitten PL, Brockman DK, Stavisky RC. 1998. Recent advances in noninvasive techniques to monitor hormone–behavior interactions. Am J Phys Anthropol 27:1–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]