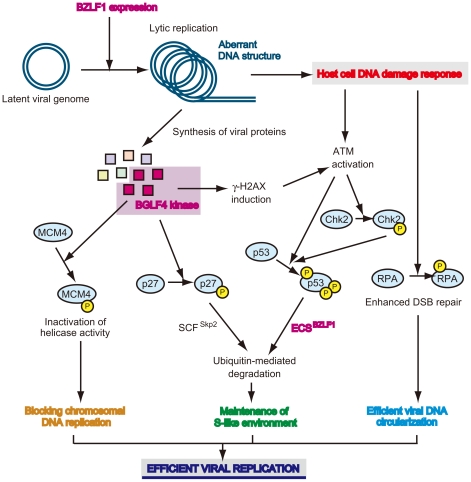

Figure 2. Viral strategy to manipulate the cellular environment for its own genome replication.

Induction of lytic replication elicits ATM-dependent host cellular DNA damage responses, because newly synthesized viral DNA is sensed as “aberrant” [9]. The ATM signaling cascade, which is modified by BGLF4 kinase-mediated γ-H2AX induction [35], phosphorylates and activates downstream molecules including CHK2 and p53. However, phosphorylated p53, which can transactivate p21Cip1/Waf1 CDK inhibitor, associates with high affinity to BZLF1 protein–formed ECS ubiquitin E3 ligase complex and then is ubiquitinated [37]. On the other hand, EBV protein kinase phosphorylates p27Kip1 CDK inhibitor, thereby leading to phosphorylation-mediated ubiquitination by the SCF complex [65]. Since these ubiquitinated proteins are degraded in a proteasome-dependent manner, an S-phase-like environment with high CDK activity required for efficient viral replication is maintained during EBV lytic infection. In parallel with this, replicative helicase activity of the MCM complex is inactivated by BGLF4-mediated phosphorylation of MCM4, causing the inhibition of chromosomal DNA replication [34]. Phosphorylated RPA induced by the DNA damage response stimulates viral DNA replication through homologous recombinational repair [40]. Taken together, EBV manipulates various signaling cascades and thereby achieves efficient viral replication.