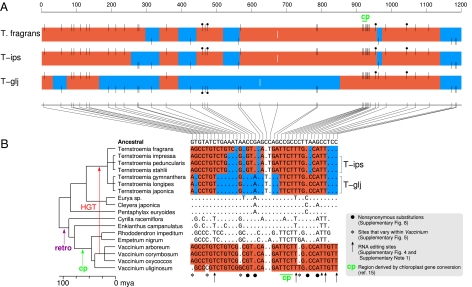

Fig. 2.

Differentially mosaic atp1 genes in Ternstroemia. (A) Multicolored boxes represent atp1 genes of the three subclades within Ternstroemia. Black vertical lines represent the 38 nucleotide positions inferred to have differed between donor and recipient atp1 genes at the time of atp1 transfer from Vaccinium to a Ternstroemia ancestor. Lines at the top of the boxes and red shading indicate sites and regions, respectively, of putatively foreign Vaccinium ancestry, whereas bottom lines and blue shading represent native sites and regions. White lines centered within the boxes represent the only two sites that otherwise differ within the Ternstroemia clade (SI Appendix, Text S5). (B) Nucleotide sequence of all sites marked in A for the 18 Ericales taxa shown. Dots indicate identities relative to the atp1 sequence inferred for the common ancestor of these taxa (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), whereas letters show nucleotide differences. Positions left blank represent gaps in sequence coverage. Retro indicates retroprocessing (SI Appendix, Text S1). Although the trichotomy at the base of Ternstroemia allowed us to place T. fragrans next to the T-ips subclade and thereby simplify the color-shading pattern, the best current estimate of Ternstroemia phylogeny (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) actually groups T. fragrans with T-glj to the exclusion of T-ips. If correct, this implies that the more intricately chimeric pattern shared by T. fragrans and T-ips reflects conversion events that were ancestral to the entire clade, with the T-glj clade sustaining subsequent conversions that reverted large segments of atp1 to native sequence along with a reciprocal change at position 961.