Abstract

Sarcoidosis is a chronic inflammatory multisystem disease of unknown etiology. We report on a woman, aged 57 years, presenting with typical sarcoidosis occurring two months after completion of a six-month course of interferon-α and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. The current observation is interesting with regard to the time elapsed between the occurrence of symptoms and antiviral treatment withdrawal, and spontaneous recovery after ten months of follow-up. Pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the development of antiviral therapy-induced sarcoidosis are discussed.

Keywords: Chronic hepatitis C, Interferon-alpha and ribavirin combination therapy, Sarcoidosis, Spontaneous recovery

Sarcoidosis is a chronic inflammatory multisystem disorder of unknown etiology associated with non-caseous granulomas.1,2 Interferon (IFN)-α is an immunomodulator used as an antiviral agent in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (CHC).3 Interferon-α has been linked to pulmonary macrophage activation, a characteristic feature in sarcoidosis.4–20 Several reports in the literature have suggested an association between IFN-α with ribavirin combination therapy and sarcoidosis.21–31 We herein report a case of a woman, aged 57 years, with CHC who developed sarcoidosis two months after completion of a six-month IFN-α and ribavirin combination therapy and spontaneously recovered after ten months of follow-up.

Case Presentation

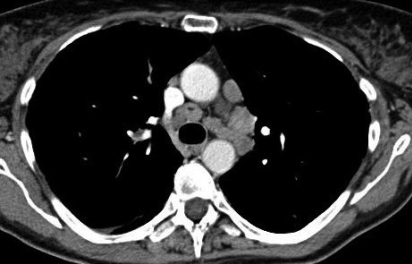

In 2007, a Caucasian woman, aged 53 years, was diagnosed with CHC genotype 3 after routine blood analyses. Her medical history was unremarkable except for smoking a half pack of cigarettes per day and a thyroidectomy for Grave’s disease in 2001, for which she was treated with levothyroxine. She started treatment with a course of the pegylated form of IFN-α2a 180 μg once weekly (starting on January 11 and ending on June 20, 2008) and ribavirin 1g per day (starting on January 11 and ending on June 26, 2008). Treatment was well-tolerated except for fatigue and myalgias. She was admitted to the emergency department on August 21, 2008 for acute dyspnea, cough, painful subcutaneous nodes located in both legs, recent weight loss, and fatigue. Body temperature was 37.3°C (100.2°F), heart rate was 85 beats/min, blood pressure was 121/74 mmHg, respirations were 20/min, and oxygen saturation was 96%. Physical examination revealed painful pretibial nodes, dry cough, inspiratory crackles on chest auscultation, chest pain with deep breaths, and enlarged liver and spleen. Chest radiograph revealed bilateral diffuse micronodular infiltrates associated with mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. Arterial blood gas in room air was as follows: pH 7.47 (normal range [NR] 7.38–7.45), Pco2 36 mmHg (NR, 32–45 mmHg), Po2 75 mmHg (NR, 75–100 mmHg), and bicarbonates 26 mmol/L (NR, 20–26 mmol/L). Laboratory tests including white blood cell count, blood chemistry and liver enzymes were within normal ranges at this time. High-resolution chest and abdominal computed tomography (CT) with contrast medium did not show pulmonary embolism but revealed several mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes and bilateral micronodular infiltrate (figure 1▶) in addition to an enlarged liver and spleen.

Figure 1.

(A) High-resolution chest CT with contrast medium demonstrating several enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. (B) High-resolution chest CT with contrast medium demonstrating bilateral micronodular infiltrate.

She was admitted to the Internal Medicine department for further evaluation. Clinical examination revealed a purplish skin nodule on the external edge of the lower eyelid, hepatosplenomegaly, fatigue, and moderate dyspnea. White blood cell count was slightly decreased to 3700/mm3 (NR, 4000–10000/mm3), in association with lymphopenia (830/mm3; NR, 1000–4000/mm3). Serological tests for Chlamydia pneumoniae, brucellosis, and Legionnella pneumophila were all negative. Mantoux test (tuberculin sensitivity test) was negative. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level was 167 U/L (NR, 35–115 U/L). Calcium serum level was 2.97 mg/dL (NR, 2.20–2.50 mg/dL), while phosphorus serum level was within normal limits. The results of pulmonary function testing were normal, except for a distal obstruction: FEV1, 2.69 L (117% of predicted value); FEV1/FVC ratio, 0.78 (100% of predicted value); TLC, 5.43 L (105% of predicted value); FEV25, 0.82 L/s (55% of predicted value); and diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide was 5.28 mmol/min/KPa (63% of predicted value). Bronchoalveolar lavage showed that CD4+ T-lymphocytes represented 61% of total lymphocytes after centrifugation and remained negative for acid-fast and fluorescence staining for mycobacteria and fungi, respectively. No evidence of granuloma was found in transbronchial or salivary gland biopsies. Skin lesions spontaneously disappeared within three days, and therefore, no skin lesion biopsy could be performed. Eye examination was unremarkable.

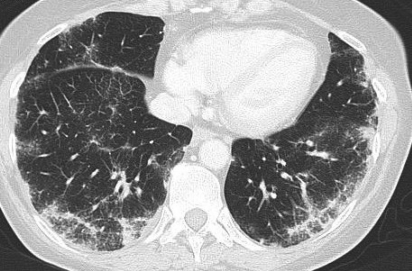

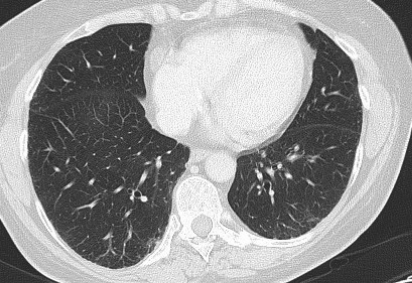

After ten months of follow-up, the patient remained totally asymptomatic, and clinical examination was normal. Chest radiography returned to normal as well as white blood cell count, ACE and calcium serum levels. Normalization of mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes and resolution of bilateral micronodular infiltrate was noted on a subsequent chest CT (figure 2▶). Angiotensin-converting enzyme serum level normalized to 53 U/L. Pulmonary function testing showed that diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide was stable (64% of predicted value).

Figure 2.

(A) After ten months follow-up, high-resolution chest CT with contrast medium demonstrating complete normalization of mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. (B) After ten months follow-up, high-resolution chest CT with contrast medium demonstrating resolution of bilateral micronodular infiltrate.

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is a multiple granulomatous disorder affecting the lung (>90% of cases), the lymphoid system (33%), liver (50–80%), eyes (11–83%) and skin (25%).1,2 Sarcoidosis has been associated with various agents whose pathogenesis involves immunological mechanisms that are only partially understood. Conversely, the immunological abnormalities of the early sarcoid reactions are well known. Sarcoid granulomas are formed in response to a persistent, and probably poorly degradable, antigenic stimulus or self-antigens that induce a local T-helper 1 (Th1)-type T-cell mediated immune response with an oligoclonal pattern.32 As a consequence of this chronic stimulation, macrophages release mediators of inflammation, locally leading to accumulation of Th1 cells at sites of ongoing inflammation and contributing to the granuloma structure.1 Histopathologically, non-caseating epithelioid granuloma is a consequence of this exaggerated cellular immune response and irritation of the normal tissue architecture in affected organs by accumulation of CD4+ T lymphocytes of the Th1 type and mononuclear phagocytes.1 The immunopathology of sarcoidosis has been best characterized in cases of pulmonary disease, in which early lesions consist of an alveolitis with a high proportion of active CD4 lymphocytes.

Although the etiology of sarcoidosis remains unknown, there is a theory that it results from exposure of genetically susceptible hosts to specific environmental agents. Recent genomic and proteomic technology has emphasized the importance of host susceptibility and gene-environment interaction in the expression of the disease.33 Possible causative agents included infectious, such as viruses or mycobacteria (especially Mycobacterium tuberculosis), organic or inorganic agents.1 Hepatitis C virus may be a cofactor in the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis in patients receiving IFN. Indeed, hepatitis C virus may activate a Th1 immune response, and some cases of sarcoidosis diagnosed in untreated patients have been reported.6,14

Interferon is produced in response to viral, bacterial, parasitic, or tumor antigens. Interferon-α is widely used in the treatment of CHC because of its anti-viral effects.3 Pegylated IFN-α and ribavirin were found to be superior to all previously proposed therapeutic regimens for sustained eradication of the hepatitis C virus.34,35 Experimental studies have shown that IFN-α is involved in the activation of T lymphocytes and subsequent production of various cytokines.36 Shiomi et al37 showed that, in patients treated with IFN-α for CHC and examined with Gallium-citrate scanning, there was a significant increase in radionuclide uptake in the lung after therapy, suggesting subclinical inflammatory process in asymptomatic individuals. The role of IFN-α in inducing predominant Th1 immune response is therefore possible. Ribavirin may also enhance Th1 response by increasing production of IL-12, IFN-γ, and TNF-α mRNA and proteins, and by decreasing the Th2 response.38,39 Consequently, enhanced Th1 immune reaction induced by the combined therapy may trigger granulomatous reactions more frequently than IFN-α monotherapy.5 This may explain why only ten cases of IFN-α-induced sarcoidosis were published between 1993 and 1999; while in the last seven years, coinciding with the generalized use of combination therapy, the number of cases reported has increased four-fold.6

To our knowledge, the first association between sarcoidosis and CHC was reported in 1993 by Blum et al40 and was directly related to the onset of IFN-α therapy. Since then, the number of cases reported annually has increased significantly, suggesting a closer association than previously suspected. The relationship between IFN-α administration and the development of sarcoidosis seemed to be clear in nearly all cases. More than 70 cases of IFN-α-induced sarcoidosis were reported in the literature. Ramos-Casals et al6 analyzed the relationship between sarcoidosis and CHC. This retrospective study described the clinical characteristics, patterns of association, and the role of antiviral therapy in 68 patients. In two-thirds of the patients, sarcoidosis was triggered during the first six months of antiviral therapy, and occurred with IFNα monotherapy in 20 cases and combined therapy with IFN-α and ribavirin in 30 cases. In eight patients, initiation of antiviral therapy for CHC reactivated pre-existing sarcoidosis. The authors suggested a possible additional role for ribavirin. Indeed, in 10 of 12 patients who received IFNα before developing sarcoidosis, the granulomatous lesion appeared during a second course of treatment with IFN and ribavirin, and not earlier with IFN alone.

The appropriate treatment of sarcoidosis has not been well-defined by the ATS/ERS/WASOG Committee (American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders).1,2 Corticosteroids can reverse the granulomatous process.41 A systematic review of the effects of corticosteroids treatment in patients provides evidence that these agents in oral or inhaled forms may lead to improvement in radiographic appearance and pulmonary function.42 The natural history of sarcoidois is highly variable, with a tendency to wax and wane, either spontaneously or in response to therapy. Spontaneous remission may occur in nearly two-thirds of patients.2 In the case of drug-induced sarcoidosis as described by Ramos-Casals et al,6 specific therapy for sarcoidosis was started in only half of the patients (21 of 42), including oral corticosteroids in 17 cases. However, improvement or remission was clearly related to discontinuation of antiviral therapy.

Although no evidence of granuloma was found in transbronchial or salivary gland biopsies, our patient had typical features of sarcoidosis (ie, fever, spontaneously resolving purplish skin nodule in external edge of the lower eyelid, chest radiography and CT images [figure 1▶], hypercalcemia, high CD4+ T lymphocytes in bronchoalveolar lavage, and significantly elevated ACE). Therefore, based on compatible clinical, biological and radiologic findings and according to the recommendations of the ATS/ERS/WASOG,1,2 the diagnosis of sarcoidosis was considered in our patient, despite the lack of histological confirmation. Transbronchial lung biopsy is the recommended procedure in most cases, but its diagnostic value depends largely on the experience of the operator, ranging from 40% to >90%.1 Based on the recommendations of the ATS/ERS/WASOG, a classic Löfgren’s syndrome may not require biopsy proof if resolution of disease is rapid and spontaneous,1 which was the case in our patient. In our case, we hypothesized that the antiviral therapy could induce sarcoidosis, based on the pathophysiological mechanisms reviewed in the literature. Immune memory could be implicated for such a hypothesis. Indeed, the current observation is interesting due to the time elapsed between symptom occurrence and antiviral therapy withdrawal. To the best of our knowledge, this will be the first case of sarcoidosis occurring several months after the end of antiviral therapy. It is unclear whether the combination therapy actually precipitated sarcoidosis de novo or even unmasked a previously subclinical case, although our patient had no clinical findings to suggest pre-existing sarcoidosis. However, a range of 30% to 60% of reported cases of sarcoidosis are asymptomatic and have been discovered by the presence of characteristic findings on routine chest radiography.43 As suggested by Ramos-Casals et al,6 in addition to the accurate evaluation of the treatment-related adverse effects, chest radiograph upon starting antiviral therapy and subsequent specific follow-up may be proposed, although no risk factor for IFN-α and/or ribavirin-induced granulomatosis has been yet identified to the best of our knowledge. Furthermore, serum calcitriol and ACE levels could be used as screening tests for drug-induced macrophage activation in future patients receiving IFN-α.44 Spontaneous rapid resolution of symptoms and the lack of severe clinical manifestation explained the lack of systemic steroid requirement in our patient. The prognosis for IFN-α-induced sarcoidosis seems to be good when the medication is discontinued,5,6 which was the case in the current observation.

In conclusion, inflammatory granulomatosis, especially sarcoidosis, may appear during, but also upon completion of, a pegylated-IFN-α2a and ribavirin combination therapy and may spontaneously resolve. Future studies may be helpful to determine predictive factors like definition of genetic risk profiles associated with this immunological adverse event and those associated with its spontaneous resolution in some cases.

References

- 1.Costalbel U, Hunninghake GW. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Statement Committee. American Thoracic Society. European Respiratory Society. World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders. Eur Respir J 1999;14:735–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, Baughman R, Cordier JF, du Bois R, Eklund A, Kitaichi M, Lynch J, Rizzato G, Rose C, Selroos O, Semenzato G, Sharma OP. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society. European Respiratory Society. World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1999;16:149–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis GL, Balart LA, Schiff ER, Lindsay K, Bodenheimer HC Jr, Perrillo RP, Carey W, Jacobson IM, Payne J, Dienstag JL, et al. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C with recombinant interferon alpha. A multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med 1989;321:1501–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leclerc S, Myers RP, Moussalli J, Herson S, Poynard T, Benveniste O. Sarcoidosis and interferon therapy: report of five cases and review of the literature. Eur J Intern Med 2003;14:237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravanel JG, McAdams HP, Plankeel JF, Butnor KJ, Sporn TA. Sarcoidosis induced by interferon therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;177:199–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramos-Casals M, Mañà J, Nardi N, Brito-Zeròn P, Xaubet A, Sãnchez-Tapias JM, Cervera R, Font J; HISPAMEC Study Group. Sarcoidosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: analysis of 68 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2005;84:69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffmann RM, Jung MC, Motz R, Gössi C, Emslander HP, Zachoval R, Pape GR. Sarcoidosis associated with interferon-alpha therapy for chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 1998;28:1058–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vallina E, Garcìa Dìez A, Gallego M, Villaverde P, Rippe ML, Arribas JM. [A case of pulmonary sarcoidosis induced by interferon alpha treatment in a female patient with hepatitis C.] [Article in Spanish] An Med Interna 2000;17:538–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pohl J, Stremmel W, Kallinowski B. [Pulmonal sarcoidosis: A rare side effect of interferon-alpha treatment for chronic hepatitis C infection.] [Article in German]. Z Gastroenterol 2000;38:951–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tahan V, Ozseker F, Guneylioglu D, Baran A, Ozaras R, Mert A, Ucisik AC, Cagatay T, Yilmazbayhan D, Senturk H. Sarcoidosis after use of interferon for chronic hepatitis C: report of a case and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci 2003;48:169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubinowitz AN, Naidich DP, Alinsonorin C. Interferon-induced sarcoidosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2003;27:279–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luchi S, Scasso A. Sarcoidosis, chronic hepatitis C and interferon-alpha: two cases. Scand J Infect Dis 2003; 35:775–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alazemi S, Campos MA. Interferon-induced sarcoidosis. Int J Clin Pract 2006;60:201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelletier F, Manzoni P, Jacoulet P, Humbert P, Aubin F. Pulmonary and cutaneous sarcoidosis associated with interferon therapy for melanoma. Cutis 2007;80:441–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doycheva D, Deuter C, Stuebiger N, Zierhut M. Interferon-alpha-associated presumed ocular sarcoidosis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophtalmol 2009;247:675–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butnor KJ. Pulmonary sarcoidosis induced by interferon-alpha therapy. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:976–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirano A, Kataoka M, Nakata Y, Takeda K, Kamao T, Hiramatsu J, Kimura G, Tanimoto Y, Kanehiro A, Tanimoto M. Sarcoidosis occurring after interferon-alpha therapy for chronic hepatitis C: report of two cases. Respirology 2005;10:529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Celik G, Sen E, Ulger AF, Kumbasar OO, Bozkaya H, Alper D, Karayalcin S. Sarcoidosis caused by interferon therapy. Respirology 2005;10:535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg HJ, Fiedler D, Webb A, Jagirdar J, Hoyumpa AM, Peters J. Sarcoidosis after treatment with interferon-alpha: a case series and review of the literature. Respir Med 2006;100:2063–2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pietropaoli A, Modrak J, Utell M. Interferon-alpha therapy associated with the development of sarcoidosis. Chest 1999;116:569–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cogrel O, Doutre MS, Marlière V, Beylot-Barry M, Couzigou P, Beylot C. Cutaneous sarcoidosis during interferon alpha and ribavirin treatment of hepatitis C virus infection: two cases. Br J Dermatol 2002;146:320–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weyer P, Cummings OW, Knox KS. A 49-year-old woman with hepatitis, confusion, and abnormal chest radiograph findings. Chest 2005;128:3076–3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savoye G, Goria O, Herve S, Riachi G, Noblesse I, Bastien L, Courville P, Lerebours E. [Probable cutaneous sarcoidosis associated with combined ribavirin and interferon-alpha therapy for chronic hepatitis C.] [Article in French]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2000;24:679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lévêque L, de Boulard A, Bielefeld P, Sgro C, Hillon P, Gabreau T, Champigneulle B, Makki H, Besancenot JF. [Sarcoidosis during the treatment of hepatitis C by interferon-alpha and ribavirin: 2 cases.] [Article in French]. Rev Med Interne 2001;22:1248–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pérez-Alvarez R, Pérez-Lòpez R, Lombraña JL, Rodrìguez M, Rodrigo L. Sarcoidosis in two patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with interferon, ribavirin and amantadine. J Viral Hepat 2002;9:75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wendling J, Descamps V, Grossin M, Marcellin P, Le Bozec P, Belaich S, Crickx B. Sarcoidosis during combined interferon alpha and ribavirin therapy in 2 patients with chronic hepatitis C. Arch Dermatol 2002;138:546–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gitlin N. Manifestation of sarcoidosis during interferon and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C: a report of two cases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;14:883–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alfageme Michavila I, Merino Sànchez M, Pérez Ronchel J, Lara Lara I, Suàrez Garcìa E, Lòpez Garrido J. [Sarcoidosis following combined ribavirin and interferon therapy: a case report and review of the literature.] [Article in Spanish] Arch Bronconeumol 2004;40:45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan KK, Dinihan I, Freiman J, Zekry A. Sarcoidosis presenting with granulomatous uveitis induced by pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy for Hepatitis C. Intern Med J 2008;38:207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bolukbas C, Bolukbas FF, Kebdir T, Canayaz L, Dalay AR, Kilic G, Ovunc O. Development of sarcoidosis during interferon alpha 2b and ribavirin combination therapy for chronic hepatitis C--a case report and review of the literature. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2005;68:432–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurst EA, Mauro T. Sarcoidosis associated with pegylated interferon alpha and ribavirin treatment for chronic hepatitis C: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:865–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seaton A, Seaton D, Leitch AG. Sarcoidosis. In: Crofton and Douglas’s Respiratory Disease. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 1989. 630.

- 33.Gerke AK, Hunninghake G. The immunology of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med 2008;29:379–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poynard T, Yuen MF, Ratziu V, Lai CL. Viral hepatitis C. Lancet 2003;362:2095–2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Häussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D, Craxi A, Lin A, Hoffman J, Yu J. Peginteferon alpha-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2002;347:975–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schattner A. Interferons and autoimmunity. Am J Med Sci 1988;295;532–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiomi S, Kuroki T, Yokogawa T, Takeda T, Nishiguchi S, Nakajima S, Tanaka T, Okamura T, Ochi H. Changes in results of Gallium-67-citrate scanning after interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C. J Nucl Med 1997;38:216–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ning Q, Brown D, Parodo J, Cattral M, Gorczynski R, Cole E, Fung L, Ding JW, Liu MF, Rotstein O, Phillips MJ, Levy G. Rivabirin inhibits viral-induced macrophage production of TNF, IL-1, the procoagulant fgI2 prothrombinase and preserves Th1 cytokine production but inhibits Th2 cytokine response. J Immunol 1998;160:3487–3493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tam RC, Pai B, Bard J, Lim C, Averett DR, Phan UT, Milovanovic T. Ribavirin polarizes human T cell responses towards a Type 1 cytokine profile. J Hepatol 1999; 30:376–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blum L, Serfaty L, Wattiaux MJ, Picard O, Cabane J, Imbert JC. [Nodules hypodermiques sarcoidosiques au cours d’une hépatite virale C traitée par interféron alpha 2b] [Article in French]. Rev Med Interne 1993;14:1161. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nunes H, Soler P, Valeyre D. Pulmonary sarcoidosis. Allergy 2005;60:565–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paramothayan S, Jones PW. Corticosteroid therapy in pulmonary sarcoidosis: a systematic review. JAMA 2002;287:1301–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas KW, Hunninghake GW. Sarcoidosis. JAMA 2003;289:3300–3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baudin B. [Angiotensin I- converting enzyme (ACE) for sarcoidosis diagnosis.] [Article in French]. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2005;53:183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]