Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to evaluate the need of axillary staging in breast cancer patients showing exclusive lymphatic drainage to the internal mammary chain (IMC).

Methods

A total of 2203 patients treated for breast carcinoma in three participating hospitals between July 2001 and July 2008 were analyzed. Only patients showing drainage to the IMC on preoperative lymphoscintigraphy were included. The number of harvested IMC sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs), axillary SLNs, and metastases were recorded. Finally, the follow-up of this group of patients was analyzed.

Results

In 25/426 patients, drainage was exclusively to the IMC. Exploration of the axilla resulted in the harvesting of blue SLNs in 9 patients (36%) and the retrieval of an enlarged lymph node in 1 patient. In 4 of the remaining 15 patients, an axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) was done. Lymph node metastases were found in 3 patients who had blue axillary SLNs and in 1 patient who underwent ALND. In the 11 patients who had no blue SLNs and no ALND, no axillary recurrences were observed during follow-up (median = 26 months).

Conclusions

Proper staging of the axilla remains crucial in patients showing exclusive drainage to the IMC. When no axillary node can be retrieved, ALND remains subject to discussion.

Introduction

The introduction of the sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy has renewed the interest in regional lymph nodes outside the axilla as a potential site of regional lymph node metastases. SLNs in the internal mammary chain (IMC) are observed on preoperative lymphoscintigraphy in up to 30% of patients [1–3]. Although harvesting these IMC-SLNs is discussed by some authors, retrieval of them is advocated by others [4, 5], not only as proof of principle but also because nonsurgical treatment may be influenced by the presence or absence of metastases in these nodes, especially when no axillary SLNs are found [6, 7].

In most patients IMC-SLNs are visualized together with axillary SLNs, while in 2.6–4% of these patients isolated lymphatic drainage to the IMC is seen, with no transport to axillary lymph nodes [7, 8]. While axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is commonly advised for patients when there are no axillary SLNs on preoperative lymphoscintigraphy, there is no agreement on what to do when there is lymphatic drainage to the IMC without drainage to the axilla [9]. The question is whether solitary IMC-SLNs are sufficient for staging, or if axillary dissection, SLN biopsy following patent blue injection, or a wait-and-see policy is required for adequate staging.

In the present study we analyzed the case histories of patients who showed isolated lymphatic drainage to internal mammary SLNs on preoperative lymphoscintigraphy. The aim of the present study was to address whether axillary staging should be done in these patients.

Materials and methods

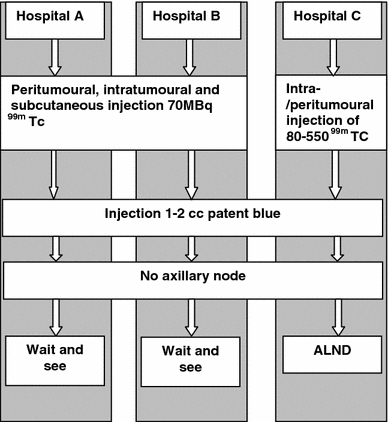

In this retrospective study, a cohort of 2203 consecutive patients diagnosed with cT1-2N0 breast cancer in three hospitals in the Middle Netherlands between July 2001 and July 2008 underwent surgery that included SLN biopsy as a staging procedure. Lymphoscintigraphy protocols were different at the three hospitals (Fig. 1). In hospitals A and B, patients received a combination of peritumoral, intratumoral, and subcutaneous injection of 99mTc nanocolloïd with an average dose of 70 MBq in a total volume of 0.6 cc of physiologic saline. In case of a nonpalpable breast tumor, the injection of the radiopharmacon was guided by ultrasound or stereotaxia. Surgery was done on the same day. In hospital C, patients were injected with 99mTc nanocolloïd (80–550 MBq) in 0.5 cc of physiologic saline intra- and peritumorally guided by ultrasound or stereotaxia using a 1- or a 2-day protocol [10]. In all hospitals the nuclear physician used both static images and a gamma-ray detection probe (Europrobe, PI Medical Diagnostics) to detect and mark the SLN. At the start of the operation, 1-2 cc of patent blue (Bleu patente′ V ‘Guerbet’) was injected peritumorally in all patients. In addition, in hospital A and B, 1 cc of patent blue was injected subcutaneously.

Fig. 1.

Sentinel node protocol for each participating hospital

Sentinel lymph node retrieval

When preoperative lymphoscintigraphy showed axillary SLNs, they were retrieved using a gamma-ray detection probe intraoperatively. A parasternal intercostal exploration was done to retrieve apparent SLNs in the IMC [2]. If no axillary SLN was visualized on preoperative lymphoscintigraphy, the axilla was still explored using the gamma-ray detection probe and patent blue irrespective of the presence of internal mammary SLNs. Axillary exploration and subsequent retrieval of a blue and/or hot SLN was considered a reliable staging procedure. In case no blue node was retrieved from the axilla, surgical strategies were different in the three hospitals: in hospital C these patients underwent ALND and in hospitals A and B a wait-and-see policy was common.

All SLNs were formalin fixed and 5-μm-thick step sections were cut at 250-μm intervals for staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemical cytokeratin-8. The size of the metastases found in the lymph nodes were defined as follows: macrometastases were metastases of 2.0 mm or larger, micrometastases were larger than 0.2 mm and smaller than 2.0 mm, and isolated tumor cells were smaller than 0.2 mm in diameter [11].

The proportion of patients with isolated lymphatic drainage to the IMC was assessed. In the selection of patients with isolated lymphatic drainage to the IMC, the yield of the patent-blue-guided axillary exploration was evaluated by describing the proportion of patients with blue sentinel nodes, the frequency of lymph node metastases when ALND was done, and the occurrence of axillary relapses when no ALND was done.

Results

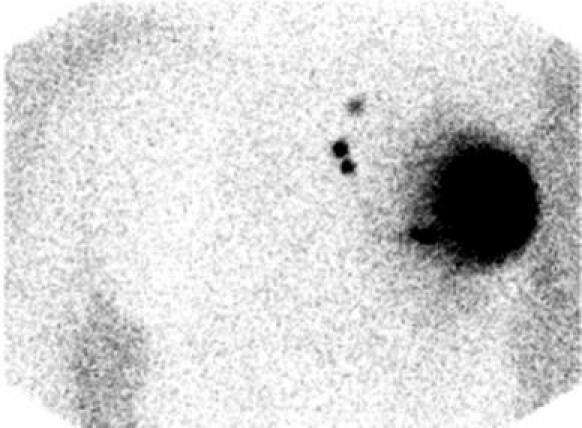

Lymphatic drainage to the IMC was observed in 426/2203 patients (19%), while exclusive IMC drainage was seen in 25/2203 (1.1%) patients (Fig. 2). Baseline characteristics of the 25 patients with exclusive drainage to the IMC are given in Table 1. In 16/25 (64%) patients the tumor was located in the upper inner quadrant.

Fig. 2.

Preoperative imaging of IMC-SLNs

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Baseline characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 60 (48–78) |

| Tumor quadrant | |

| Upper outer | 6 (24%) |

| Upper inner | 16 (64%) |

| Lower inner | 2 (8%) |

| Central | 1 (4%) |

| Tumor histology | |

| Ductal | 19 (76%) |

| Lobular | 3 (12%) |

| Ductolobular | 2 (8%) |

| Papillary | 1 (4%) |

| Median tumor size (mm) | 15 (5–80) |

| Estrogen receptor expression | 21 (84%) |

| Progesterone receptor expression | 17 (68%) |

| Her2Neu overexpression | 5 (20%) |

| B&R | |

| 1 | 9 (36%) |

| 2 | 8 (32%) |

| 3 | 7 (28%) |

| Unknown | 1 (4%) |

| MAI | 5 (0-45) |

MAI mitose activity index, B&R Bloom and Richardson grade

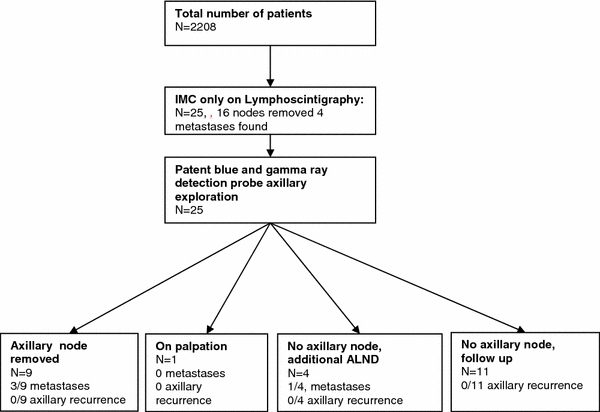

In the 25 patients with exclusive lymphoscintigraphic visualization of SLN drainage to the IMC, the lymph nodes could be extirpated successfully in 16 patients (64%). In 12 of these 16 patients the node was hot and in 4 patients the node was hot and blue. Metastases were detected in the IMC-SLNs in 4 of the 16 patients (Fig. 3): isolated tumor cells in 2 patients, micrometastasis in 1 patient, and macrometastasis in 1 patient.

Fig. 3.

Flowchart

In addition to the exploration of the IMC, the axilla was explored for hot and/or patent-blue-containing SLNs. Additional nodes were retrieved from the axilla in 14/25 patients. Ten patients underwent a successful SLN retrieval from the axilla: in nine patients a blue lymph node was retrieved from the axilla and in another patient an enlarged node was removed. The remaining four patients underwent ALND. Four of the 14 patients who underwent axillary staging had axillary lymph node metastases: in three patients who had SLN staging of the axilla and in 1 patient who had ALND following a failed exploration for a blue SLN. Axillary lymph node involvement was categorized as macrometastasis (n = 1), micrometastasis (n = 2), and isolated tumor cells (n = 1) (Table 2). Additional axillary staging by SLN biopsy or ALND in patients with exclusive drainage to the IMC on preoperative lymphoscintigraphy resulted in an increase in frequency of regional lymph node metastases from 16 to 28% (4/25 vs. 7/25 patients). One patient had axillary metastases concomitant with IMC metastases. Two patients with axillary metastases had their postsurgical treatment adjusted to adjuvant chemotherapeutic treatment and one patient chose not to receive additional chemotherapy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sentinel node and tumor characteristics

| Patient | Age (years) | Tumor size (mm) | Location of metastasis | Grade of metastasis | Recurrence | Additional treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | 70 | Axillary | Micro | No | Chemotherapy |

| 2 | 59 | 9 | Axillary | ITC | Yes | No |

| 3 | 57 | 10 | Axillary | Micro | No | No |

| 4 | 73 | 19 | IMC | Micro | No | No |

| 5 | 62 | 16 | IMC | ITC | No | No |

| 6 | 60 | 25 | IMC | ITC | No | No |

| 7 | 58 | 16 | Axillary and IMC | Macro | No | Chemotherapy |

The overall median follow-up was 26 months (range = 4–82). A total of 3/25 (12%) patients died after a median of 53 months (range = 21–72). One of these patients had undergone removal of an axillary node containing isolated tumor cells (ITC). This patient received locoregional radiotherapy on the IMC and no axillary dissection had been performed. In another patient only an IMC-SLN without tumor cells was harvested and no axillary nodes were removed. These two patients died due to progression of the breast carcinoma; one suffered bone metastases and the other suffered skin recurrence and distant metastases to liver and lungs. The third patient showed micrometastases in the IMC; no axillary dissection was performed and locoregional radiotherapy was given on the IMC. This patient was diagnosed with simultaneous esophageal carcinoma and died due to progression of this carcinoma. In none of these patients was axillary recurrence observed.

Discussion

Although the utility of harvesting internal mammary chain SLNs is discussed by some authors, we strongly believe that there is a rationale for retrieving these nodes. Tumor staging will be more accurate after histological judgment of all sentinel lymph nodes, especially in the absence of axillary SLNs that might influence adjuvant treatment [2, 6, 7]. However, we realize that this debate will continue as long as there are no reliable results of randomized trials regarding the treatment principle of intramammary chain metastases.

In this large retrospective cohort of patients who underwent SLN biopsy as part of breast cancer surgery, 1% had exclusive lymphoscintigraphic drainage to the IMC. Axillary staging revealed metastases in a clinically relevant additional proportion of patients. We realize that the retrospective design of the study has its drawbacks. Despite this, it is this one of the largest studies of this important clinical dilemma [6, 7].

The type of nuclear protocol is important to the number of nodes found in the IMC. After intra- or peritumoral injection of the radiopharmacon, the number of nodes found in the IMC is higher than after subcutaneous injection. This can be explained by the differences in drainage patterns of the breast. Tumors deeper in the breast more often tend to drain to the IMC than do superficial tumors. The deep and the superficial drainage systems in the breast are not connected, so when injecting only subcutaneously, the deep drainage system is missed and the SLNs connected to the deep drainage system are missed as well [12]. In this study all patients had an intra- or a peritumoral injection, and in hospitals A and B in combination with a subcutaneous injection. All patients underwent axillary exploration, although in a SLN could not be harvested in all cases. Furthermore, it is known that tumors in the upper inner quadrant of the breast tend to drain more often to the IMC [10, 13], and indeed most patients in this study had tumors located in the upper inner quadrant of the breast.

Despite the absence of lymphoscintigraphic axillary drainage, axillary staging detected lymph node metastases with similar frequency as SLN biopsy revealed in the IMC node. The observed absence of lymphoscintigraphic drainage to the axilla could not be attributed to blockage of this path by massive axillary lymph node involvement, as suggested by others [7]. Instead, the extent of metastatic lymph node involvement was comparable and limited in both the axilla and the IMC, as described by others [14, 15]. Furthermore, the presence of lymph node metastases in the axilla and the IMC was not interdependent. Hence, additional axillary staging led to an increased overall frequency of regional lymph node metastases.

As described earlier, younger age could influence the detection of SN in the IMC [2]; however, in this study we could not confirm this. Tumor stage (I-II) is also described as being a factor in identifying IMC-SLNs and tumor positivity in these nodes. Indeed, the majority of the patients described in this study had stage I-II breast cancer. One patient had an 8-cm tumor and another patient had a 7-cm tumor on histopathology. According to the Dutch guidelines for breast carcinoma [16], patients with tumors clinically smaller than 5 cm (T2 tumors) undergo SN biopsy and tumors larger than 5 cm undergo primary ALND. Both these patients had a secondary ALND which showed no additional metastases.

In this study, the IMC-SLN could not be harvested in nine patients. Others described a conservative approach to harvesting IMC-SLNs as a limited number of patients would benefit from it and the possible morbidity of harvesting IMC-SLNs should weigh against the benefit. We demonstrated that harvesting the IMC-SLN did not change the adjuvant treatment in most cases, so indeed a critical approach to selection of patients in whom the IMC-SLN can be harvested is justified [5.]

The retrieval from the axilla of blue SLNs that contain metastases demonstrates the complementary aspect of patent blue and radioactive tracer injection when performing SLN biopsy in breast cancer patients. In that respect, our findings are in line with the observation of others [6, 7, 17]. Van der Ploeg et al. [7] performed patent-blue-guided axillary exploration in a group of 82 patients with exclusive lymphoscintigraphic drainage to the IMC and blue SLNs were identified in 62 of these patients. We confirm the need for additional axillary staging in patients with exclusive lymphoscintigraphic drainage to the IMC [18].

Optimal staging of breast cancer patients becomes ever more important. Even ITCs and micrometastases in regional lymph nodes may have a prognostic effect, and the indications for adjuvant chemotherapy will be expanded to patients with them [19]. In the present study, in those patients with no axillary drainage on lymphoscintigraphy, three patients were proposed to receive adjuvant chemotherapy because of additional metastases in the axilla.

Whether to perform an axillary dissection when exploration for a blue SLN is unsuccessful is more difficult to answer. Some authors argue that in the case of successful retrieval of IMC-SLNs, axillary exploration for blue SLNs is a sufficient means of staging. In their view, when exploration of the axilla does not reveal a blue SLN, there is no lymphatic drainage to the axilla and an ALND may be omitted safely [7]. In line with their results, we observed no axillary recurrences in the patients in the wait-and-see group. However, our data can be used to support the ALND policy, too, since axillary lymph node metastases were found in one patient in whom an ALND was performed when no axillary SN could be identified. Furthermore, the survival and recurrence rates of the patients in this study are comparable to those in the literature [3, 7, 15].

In order to reach consensus on whether an additional ALND is needed when no other than IMC-SLN’s are found, more data are needed. Because a prospective randomized trial on this subject probably will not be feasible, we encourage other authors to present their data likewise.

In conclusion, when preoperative lymphoscintigraphy shows exclusive lymphatic drainage to the internal mammary chain, proper staging should include exploration of the axilla for blue SLNs. Metastases can be found in a relevant additional proportion of patients and postsurgical treatment could be adjusted accordingly. Performing an ALND when no axillary node can be retrieved remains subject to debate.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript claim no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Estourgie SH, Tanis PJ, Nieweg OE, et al. Should the hunt for internal mammary chain sentinel nodes begin? An evaluation of 150 breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(8):935–941. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2003.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madsen E, Gobardhan P, Bongers V, et al. The impact on post-surgical treatment of sentinel lymph node biopsy of internal mammary lymph nodes in patients with breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(4):1486–1492. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9230-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourre JC, Payan R, Collomb D, et al. Can the sentinel lymph node technique affect decisions to offer internal mammary chain irradiation? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36(5):758–764. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-1034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coombs NJ, Boyages J, French JR, et al. Internal mammary sentinel nodes: ignore, irradiate or operate? Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(5):789–794. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wouters MW, van Geel AN, Menke-Pluijmers M, et al. Should internal mammary chain (IMC) sentinel node biopsy be performed? Outcome in 90 consecutive non-biopsied patients with a positive IMC scintigraphy. Breast. 2008;17(2):152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heuts EM, van der Ent FW, von Meyenfeldt MF, et al. Internal mammary lymph drainage and sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer—a study on 1008 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35(3):252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.06.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Ploeg I, Tanis PJ, Valdes Olmos RA, et al. Breast cancer patients with extra-axillary sentinel nodes only may be spared axillary lymph node dissection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(11):3239–3243. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0120-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estourgie SH, Nieweg OE, Olmos RA, et al. Lymphatic drainage patterns from the breast. Ann Surg. 2004;239(2):232–237. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000109156.26378.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barone JE, Tucker JB, Perez JM, et al. Evidence-based medicine applied to sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with breast cancer. Am Surg. 2005;71(1):66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Esser S, Hobbelink M, Van Isselt JW, et al. Comparison of a 1-day and a 2-day protocol for lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with nonpalpable breast cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36(9):1383–1387. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1114-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singletary SE, Connolly JL. Breast cancer staging: working with the sixth edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(1):37–47. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suami H, Pan WR, Mann GB, et al. The lymphatic anatomy of the breast and its implications for sentinel lymph node biopsy: a human cadaver study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(3):863–871. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9709-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Straalman K, Kristoffersen US, Galatius H, et al. Factors influencing sentinel lymph node identification failure in breast cancer surgery. Breast. 2008;17(2):167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avisar E, Molina MA, Scarlata M, et al. Internal mammary sentinel node biopsy for breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2008;196(4):490–494. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Domenech-Vilardell A, Bajen MT, Benitez AM, et al. Removal of the internal mammary sentinel node in breast cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2009;30(12):962–970. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328330addf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dutch guidelines for breast carcinoma 2010, www.ikcnet.nl (dutch integrated cancer registry)

- 17.Cserni G, Rajtar M, Boross G, et al. Comparison of vital dye-guided lymphatic mapping and dye plus gamma probe-guided sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer. World J Surg. 2002;26(5):592–597. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veronesi U, Arnone P, Veronesi P, et al. The value of radiotherapy on metastatic internal mammary nodes in breast cancer. Results on a large series. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(9):1553–1560. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Boer M, van Deurzen CH, van Dijck JA, et al. Micrometastases or isolated tumor cells and the outcome of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(7):653–663. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]