Abstract

The design and synthesis of new inhibitor analogues for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) phosphatase PtpB is described. Analogues were synthesized by incorporation of two common and effective phosphate mimetics, the isothiazolidinone (IZD) and the difluoromethylphosphonic acid (DFMP). The basic scaffold of the inhibitor was identified from structure-activity relationships established for a previously published isoxazole inhibitor, while the phosphate mimetics were chosen based on their proven cell permeability and activity when incorporated into previously reported inhibitors for the phosphatase PTP1B. The inhibitory activity of each compound was evaluated, and each was found to have low or submicromolar affinity for PtpB.

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic, infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). Each year, nearly 2 million deaths occur out of over 13 million active cases of TB,1 and current treatment of drug-sensitive strains requires 6-9 months to fully eradicate the infection. New Mtb drugs that act on novel targets are needed to shorten treatment time and address the emergence of antibiotic resistance. Mtb PtpB is a secreted virulence factor that functions within human macrophages, and chemical interference with PtpB function has been shown to reduce bacterial loads in an Mtb macrophage infection model.2 PtpB is attractive as a therapeutic target due to its localization outside of the unusually thick mycobacterial cell wall, which is difficult to penetrate and leads to long treatment times for tuberculosis (TB).

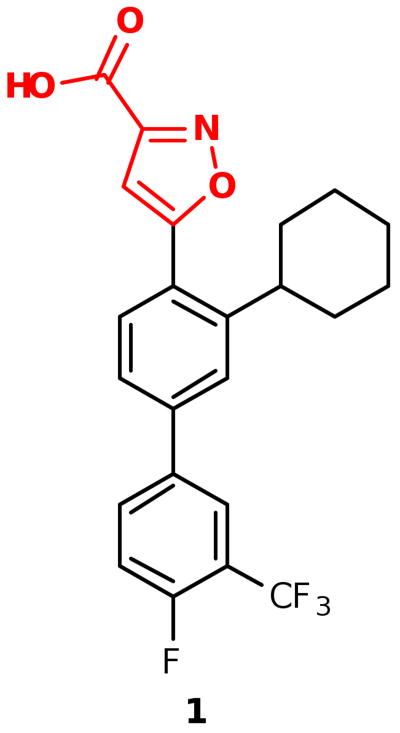

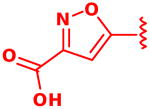

We previously reported the development of isoxazole carboxylic acid inhibitor 1 for PtpB, using the substrate activity screening (SAS) method, a novel fragment-based approach for the identification of phosphatase inhibitors (Figure 1).3 Development of the isoxazole inhibitor revealed that ortho substituents are preferred for optimal PtpB binding, with the cyclohexyl group providing the most favorable enzyme interactions. In order to compare binding affinity and cell activity, we desired a route to analogueous inhibitors incorporating other commonly used phosphate mimetics.

Figure 1.

Previously reported isoxazole PtpB inhibitor 1.

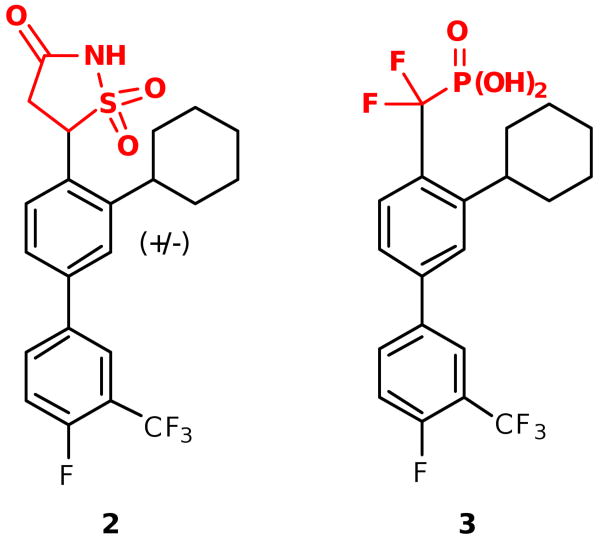

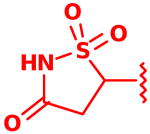

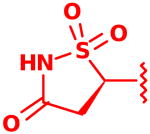

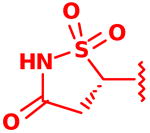

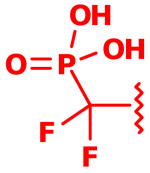

A variety of phosphate isosteres have been reported and could be introduced in place of the isoxazole,4 but many contain at least two acidic sites and lead to inhibitors with poor cellular permeability.5 We therefore chose two phosphate mimetics that have been effectively used in inhibitors of PTP1B, a human phosphatase targeted for diabetes treatment, with good cell permeability and activity, namely the isothiazolidinone (IZD) and difluoromethylphosphonic acid (DFMP) mimetics (Figure 2). The monoanionic IZD6 phosphate mimetic was developed by Incyte through structure-based design,6g while the DFMP pharmacophore is a commonly used phosphate mimetic that has been investigated extensively in the literature.7 Despite being dianionic, the DFMP isostere has recently been shown by Merck to be cell permeable and orally bioavailable in animals when incorporated into nonpeptidic inhibitors of PTP1B.8

Figure 2.

New PtpB inhibitor analogues incorporating the IZD and DFMP phosphate mimetics.

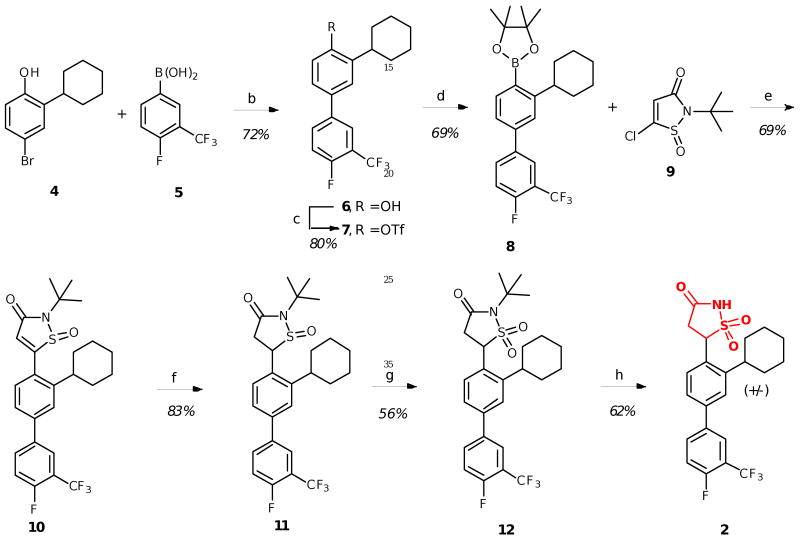

Several syntheses have been reported for the IZD isostere.6a,6c-e However, due to considerable steric interactions introduced by the cyclohexyl group ortho to the IZD isostere in 2, implementation of successful cross-coupling methods for installing the isostere posed a significant challenge (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of IZD inhibitor 2. Reagents and conditions: (a) Pd(OAc)2, KF, CyJohnPhos, THF, 50 °C; (b) Tf2O, Et3N, CH2Cl2, -78 °C; (c) Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3, K3PO4, SPhos, B2pin2, toluene, 100 °C; (d) Pd(OAc)2, K3PO4, SPhos, cat. H2O, THF, 60 °C; (e) NaBH4, MeOH, 0 °C; (f) m-CPBA, CH2Cl2, 0 °C to rt; (g) d-TFA, H2O, 80 °C.

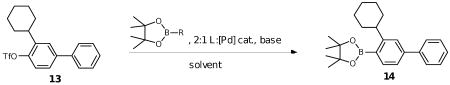

First, o-cyclohexyl phenol 4 was subjected to Suzuki coupling with 4-fluoro-3-trifluoromethyl boronic acid 5 to afford the biaryl phenol 6. Treatment with triflic anhydride under basic conditions then afforded triflate 7, which was then coupled with bis(pinacolato)diboron to provide boronic ester 8.9 This coupling step required significant optimization due to the presence of the sterically encumbered ortho cyclohexyl group, which has not been previously reported as a partner in Suzuki couplings (Table 1). To determine optimal conditions for boration of hindered triflate 7, we screened conditions using the biphenyl model substrate 13. Standard Suzuki conditions for coupling with bis(pinacolato)diboron failed to produce product (entry 1), as did standard Buchwald conditions using cyclohexyl JohnPhos as the ligand (entry 2). Similarly, all attempts to couple with pinacol borane gave no reaction (entries 3-4). Finally, inclusion of the Buchwald ligand SPhos9-10 afforded product, albeit in low yield (entry 5). Increasing the temperature to 130 °C decreased the yield, likely due to protodeborylation of the product (entry 6), but switching to the precatalyst Pd2(dba)3 in addition to reversed-phase purification of the somewhat unstable boronic ester improved the yield significantly to 66% (entry 7). Upon applying the same conditions to the desired triflate 7, the pinacol ester 8 was obtained in 69% yield (Scheme 1).

Table 1.

Coupling of model biphenyl triflate 13 to afford model biphenyl boronic ester 14.

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | [Pd] cat. | Ligand | Base | Solvent | Temp (°C) | Time (h) | %Yielda |

| 1 | Bpin | Pd(dppf)Cl2 | -- | KOAc | dioxane | 80 | 26 | 0% |

| 2 | Bpin | Pd(OAc)2 | CyJohnPhos | KF | toluene | 100 | 17 | 0% |

| 3 | H | Pd(PPh3)4 | -- | Et3N | dioxane | 80 | 4 | 0% |

| 4 | H | Pd(dppf)Cl2 | -- | Et3N | dioxane | 70 | 27 | 0% |

| 5 | Bpin | Pd(OAc)2 | SPhos | K3PO4 | toluene | 100 | 15 | 28% |

| 6 | Bpin | Pd(OAc)2 | SPhos | K3PO4 | toluene | 130 | 16 | 14% |

| 7 | Bpin | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | SPhos | K3PO4 | toluene | 110 | 17 | 66% |

Yield was determined by mass balance after silica gel column chromatography.

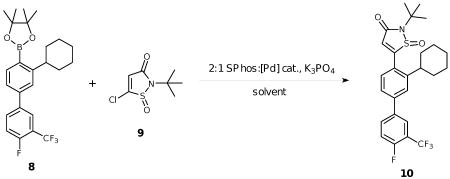

Upon developing conditions to successfully prepare the hindered boronic ester 8, it was then necessary to carry out Suzuki cross-coupling with heterocycle 9. As shown in Table 2, to achieve a successful cross-coupling the reaction parameters required careful optimization, including choice of precatalyst, additive, and reaction temperature. The cross-coupling conditions used to prepare boronic ester 8 also afforded product 10, but in low yield (15%), likely due to competitive formation of ring opened byproducts from either heterocycle 9 or product 10, as determined by NMR analysis (entry 1). We observed similar decomposition byproducts when using an amination precatalyst developed by Hartwig (entries 2-3), which was designed to increase the rate of oxidative addition, a step that is often rate-limiting in the Suzuki catalytic cycle.11 Ultimately, we found that use of Pd(OAc)2 as the precatalyst with inclusion of water enabled formation of product at reduced temperatures, which minimized the formation of undesired ring-opened byproducts (entry 4). Increasing the amount of water and the reaction time ultimately gave the coupled product in 69% yield (entry 5). Compound 10 was then reduced with sodium borohydride, followed by oxidation to sulfone 12 with m-CPBA. Final TFA deprotection then gave the desired IZD inhibitor 2 in racemic form.

Table 2.

Coupling of biphenyl boronic ester 8 and heterocycle 9 to afford coupled product 10.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | [Pd] cat. | Solvent | Temp (°C) | Time (h) | %Yielda |

| 1 | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | toluene | 100 | 20 | 15% |

| 2 | Pd[P(o-tol)3]2 | toluene | 60 | 20 | 15% |

| 3 | Pd[P(o-tol)3]2 | toluene | 100 | 23 | 28% |

| 4 | Pd(OAc)2 | THF, 1 mol% H2O | 60 | 20 | 54% |

| 5 | Pd(OAc)2 | THF, 10 mol% H2O | 60 | 24 | 69% |

Yield was determined by mass balance after silica gel column chromatography.

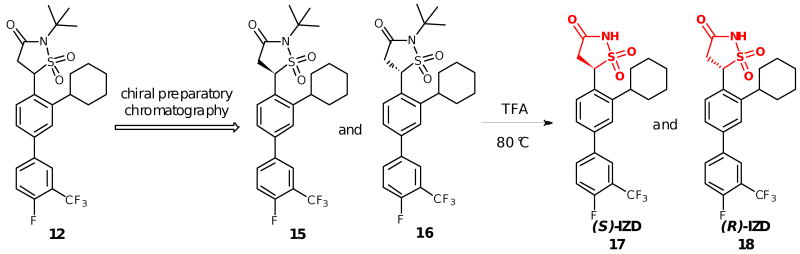

Based on previous studies of IZD inhibitors for PTP1B,6a,6c-g we reasoned that Mtb PtpB should bind one IZD enantiomer preferentially, and we therefore separated the two enantiomers 17 and 18 by subjecting compound 12 to chiral preparatory chromatography (Scheme 2),12 followed by the same TFA treatment described above to remove the tert-butyl protecting group from compounds 15 and 16. Compounds 15 and 16 were found to have >99% ee and >99% purity after separation and isolation.

Scheme 2.

Isolation of enantiomerically pure IZD inhibitors 17 and 18.

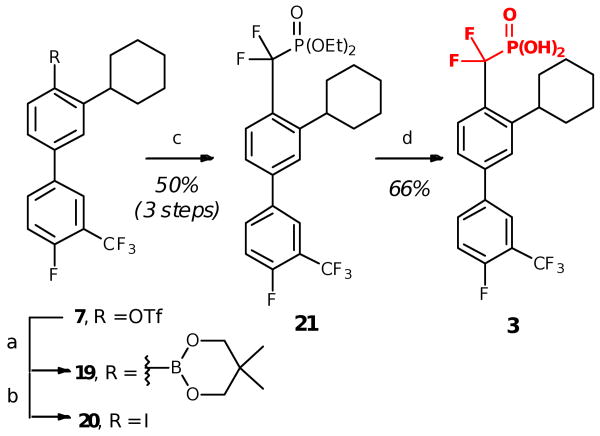

To complete the PtpB inhibitor panel and provide further comparison of phosphate mimetics in terms of PtpB binding affinity, we also developed a route to DFMP analogue 3. Several synthetic approaches have been reported for installation of the DFMP isostere and could be used in the synthesis of the DFMP compound.13 We chose a relatively mild and straightforward cross coupling approach between aryl iodide 20 and a commercially available diethyl phosphonate,13c because this strategy is compatible with a variety of functional groups and enables late stage incorporation of the DFMP warhead (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of DFMP inhibitor 3. Reagents and conditions: (a) bis(neoglycolato)diboron, K3PO4, SPhos, Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3, toluene, 100 °C; (b) NaI, chloramine-T, 50% aq THF; (c) diethyl(bromodifluoromethyl)phosphonate, Zn°, CuBr, DMA; (c) TMSI, CHCl3.

Synthesis of DFMP analogue 3 began by coupling bis(neoglycolato)diboron with triflate intermediate 7 used in the synthesis of the IZD inhibitor (Scheme 3). This was followed by iodination with in situ-generated ICl to form the aryl iodide 20, then copper and zinc-mediated coupling with diethyl(bromodifluoromethyl)phosphonate to afford the aryl phosphonate 21. Final deprotection then afforded the desired DFMP inhibitor 3.

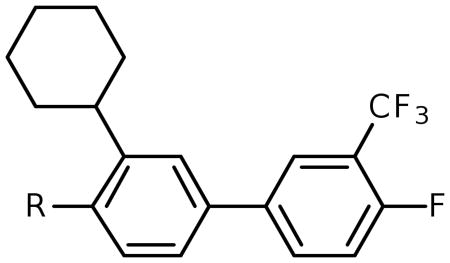

Following isolation, each compound was assayed versus Mtb PtpB (Table 3). To rule out non-specific aggregation-based enzyme inhibition,14 the detergent Triton X-100 was included in all assays, and Hill slopes were measured and found to be close to -1.0 for all compounds (see ESI). Racemic IZD inhibitor 2 was found to have a Ki of 3.7 μM versus PtpB, which is only modestly weaker than isoxazole scaffold 1, while the enantiomerically pure IZD compounds 17 and 18 were found to have Ki values of 2.4 and 8.0 μM, respectively.15 The chiral discrimination found for these IZD enantiomers is more modest than for IZD inhibitors of PTP1B.6e,6g DFMP compound 3 was found to have a Ki of 0.69 μM versus PtpB, and represents the most potent inhibitor in the series.16

Table 3.

Assay of isoxazole inhibitor 1, IZD inhibitors 2, 17 and 18, and DFMP inhibitor 3 versus PtpB.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| # | R | Ki (μM)a |

| 1 |  |

1.3 ± 0.6b |

| 2 |  |

3.7 ± 0.6 |

| 17 |  |

2.4 ± 0.0 or 8.0 ± 0.4 |

| 18 |  |

2.4 ± 0.0 or 8.0 ± 0.4 |

| 3 |  |

0.69 ± 0.21 |

Compounds were assayed in duplicate and repeated in triplicate.

Assays were run with a new batch of enzyme as compared to previous reports and reproducibly gave a higher Ki value.

The results of this study demonstrate that the isoxazole, IZD, and DFMP pharmacophores can each be incorporated into effective inhibitors of Mtb PtpB. These inhibitors represent a useful set of tool compounds for further dissection of the biochemical role of PtpB in TB infection, because inhibitors are expected to have different physicochemical properties, which will impact important factors that contribute to compound efficacy such as cell permeability, protein binding, oral bioavailability, and clearance rates.

In conclusion, two new, nonpeptidic inhibitor analogues for Mtb PtpB have been identified. Each of these compounds is based on the optimal scaffold previously identified using the SAS method,3 a novel fragment-based approach for phosphatase inhibitor development. Inhibitors 2 and 3 incorporate the IZD and DFMP phosphate mimetics, respectively, in place of the isoxazole carboxylic acid warhead developed for compound 1. These mimetics were chosen based on previous incorporation into inhibitors of the phosphatase PTP1B, an enzyme targeted for diabetes treatment. The IZD and DFMP analogues show comparable inhibitory activity to isoxazole inhibitor 1 in terms of binding affinity, and they are expected to vary in terms of cell permeability and activity. The entire panel of inhibitor analogues is therefore currently being evaluated in TB-infected cells and future work will include evaluation in animal infection models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.A.E. acknowledges the support of the NIH (GM054051). K.A.R. was supported by an ACS Division of Medicinal Chemistry Pre-doctoral fellowship, sponsored by Eli Lilly. C.G. acknowledges the support of the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation (grant 8999).

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental procedures, analytical data, and NMR spectra for all novel compounds; procedure for enzyme assays. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Contributor Information

Christoph Grundner, Email: christoph.grundner@sbri.org.

Jonathan A. Ellman, Email: jellman@berkeley.edu.

Notes and references

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report. 2009 http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2009/pdf/full_report.pdf.

- 2.(a) Zhou B, He Y, Zhang X, Xu J, Luo Y, Wang Y, Franzblau S, Yang Z, Chan R, Liu Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909133107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Beresford N, Patel S, Armstrong J, Szoor B, Fordham-Skelton AP, Tabernero L. Biochem J. 2007;406:13–18. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Grundner C, Ng HL, Alber T. Structure. 2005;13:1625–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Singh R, Rao V, Shakila H, Gupta R, Khera A, Dhar N, Singh A, Koul A, Singh Y, Naseema M, Narayanan PR, Paramasivan CN, Ramanathan VD, Tyagi AK. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:751–762. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Beresford NJ, Mulhearn D, Szczepankiewicz B, Liu G, Johnson ME, Fordham-Skelton A, Abad-Zapatero C, Cavet JS, Tabernero L. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:928–36. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soellner MB, Rawls KA, Grundner C, Alber T, Ellman JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9613–9615. doi: 10.1021/ja0727520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Rye CS, Baell JB. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:3127–3141. doi: 10.2174/092986705774933452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang ZY. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:209–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.083001.144616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kotoris CC, Chen MJ, Taylor SD. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8:3275–3280. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00598-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu X. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:6321–6327. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Sparks RB, Polam P, Zhu W, Crawley ML, Takvorian A, McLaughlin E, Wei M, Ala PJ, Gonneville L, Taylor N, Li Y, Wynn R, Burn TC, Liu PCC, Combs AP. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:736–740. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Combs Andrew P, Glass B, Galya Laurine G, Li M. Org Lett. 2007;9:1279–82. doi: 10.1021/ol0701262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yue EW, Wayland B, Douty B, Crawley ML, McLaughlin E, Takvorian A, Wasserman Z, Bower MJ, Wei M, Li Y, Ala PJ, Gonneville L, Wynn R, Burn TC, Liu PCC, Combs AP. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;14:5833–5849. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Combs AP, Zhu W, Crawley ML, Glass B, Polam P, Sparks RB, Modi D, Takvorian A, McLaughlin E, Yue EW, Wasserman Z, Bower M, Wei M, Rupar M, Ala PJ, Reid BM, Ellis D, Gonneville L, Emm T, Taylor N, Yeleswaram S, Li Y, Wynn R, Burn TC, Hollis G, Liu PCC, Metcalf B. J Med Chem. 2006;49:3774–3789. doi: 10.1021/jm0600904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ala PJ, Gonneville L, Hillman MC, Becker-Pasha M, Wei M, Reid BG, Klabe R, Yue EW, Wayland B, Douty B, Polam P, Wasserman Z, Bower M, Combs AP, Burn TC, Hollis GF, Wynn R. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32784–32795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Ala PJ, Gonneville L, Hillman M, Becker-Pasha M, Yue EW, Douty B, Wayland B, Polam P, Crawley ML, McLaughlin E, Sparks RB, Glass B, Takvorian A, Combs AP, Burn TC, Hollis GF, Wynn R. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38013–38021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607913200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Combs AP, Yue EW, Bower M, Ala PJ, Wayland B, Douty B, Takvorian A, Polam P, Wasserman Z, Zhu W, Crawley ML, Pruitt J, Sparks R, Glass B, Modi D, McLaughlin E, Bostrom L, Li M, Galya L, Blom K, Hillman M, Gonneville L, Reid BG, Wei M, Becker-Pasha M, Klabe R, Huber R, Li Y, Hollis G, Burn TC, Wynn R, Liu P, Metcalf B. J Med Chem. 2005;48:6544–6548. doi: 10.1021/jm0504555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Sun JP, Fedorov AA, Lee SY, Guo XL, Shen K, Lawrence DS, Almo SC, Zhang ZY. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12406–12414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shen K, Keng YF, Wu L, Guo XL, Lawrence DS, Zhang ZY. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47311–47319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sarmiento M, Wu L, Keng YF, Song L, Luo Z, Huang Z, Wu GZ, Yuan AK, Zhang ZY. J Med Chem. 2000;43:146–155. doi: 10.1021/jm990329z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Taing M, Keng YF, Shen K, Wu L, Lawrence DS, Zhang ZY. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3793–3803. doi: 10.1021/bi9813781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yao ZJ, Ye B, Wu XW, Wang S, Wu L, Zhang ZY, Burke TR., Jr Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;6:1799–1810. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Puius YA, Zhao Y, Sullivan M, Lawrence DS, Almo SC, Zhang ZY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13420–13425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han Y, Belley M, Bayly CI, Colucci J, Dufresne C, Giroux A, Lau CK, Leblanc Y, McKay D, Therien M, Wilson MC, Skorey K, Chan CC, Scapin G, Kennedy BP. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:3200–3205. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Billingsley K, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3358–3366. doi: 10.1021/ja068577p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Barder TE, Walker SD, Martinelli JR, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4685–4696. doi: 10.1021/ja042491j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Barder TE, Buchwald SL. Org Lett. 2004;6:2649–2652. doi: 10.1021/ol0491686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogata T, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:13848–9. doi: 10.1021/ja805810p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiral separation was performed by Lotus Separations, LLC, Washington Road, Frick Lab, Room 201, Princeton, NJ 08544-0000: http://www.lotussep.com/

- 13.(a) Hussain M, Ahmed V, Hill B, Ahmed Z, Taylor S. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;16:6764–6777. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ibrahimi OA, Wu L, Zhao K, Zhang ZY. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:457–460. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yokomatsu T, Murano T, Suemune K, Shibuya S. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:815–822. [Google Scholar]; (d) Solas D, Hale R, Patel D. J Org Chem. 1996;61:1537–1539. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Coan K, Maltby D, Burlingame A, Shoichet B. J Med Chem. 2009;52:2067–2075. doi: 10.1021/jm801605r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shoichet B. Drug Disc Today. 2006;11:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Seidler J, McGovern S, Doman T, Shoichet B. J Med Chem. 2003;46:4477–4486. doi: 10.1021/jm030191r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) McGovern S, Helfand B, Feng B, Shoichet B. J Med Chem. 2003;46:4265–4272. doi: 10.1021/jm030266r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Note that the absolute configuration of each compound has not been established; repeated attempts at crystallization failed to produce crystals sufficient for X-Ray analysis, likely due to the inability of these compounds to pack with the necessary co-solvents.

- 16.For examples of other previously reported PtpB inhibitors, see:; (a) Tan L, Wu H, Yang P, Kalesh K, Zhang X, Hu M, Srinivasan R, Yao S. Org Lett. 2009;11:5102–5105. doi: 10.1021/ol9023419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Noeren-Mueller A, Wilk W, Saxena K, Schwalbe H, Kaiser M, Waldmann H. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:5973–5977. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Correa IR, Jr, Noeren-Mueller A, Ambrosi HD, Jakupovic S, Saxena K, Schwalbe H, Kaiser M, Waldmann H. Chem--Asian J. 2007;2:1109–1126. doi: 10.1002/asia.200700125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.