Abstract

Prevotella species are members of the bacterial oral flora and are opportunistic pathogens in polymicrobial infections of soft tissues. Antibiotic resistance to tetracyclines is common in these bacteria, and the gene encoding this resistance has been previously identified as tetQ. The tetQ gene is also found on conjugative transposons in the intestinal Bacteroides species; whether these related bacteria have transmitted tetQ to Prevotella is unknown. In this study, we describe our genetic analysis of mobile tetQ elements in oral Prevotella species. Our results indicate that the mobile elements encoding tetQ in oral species are distinct from those found in the Bacteroides. The intestinal bacteria may act as a reservoir for the tetQ gene, but Prevotella has incorporated this gene into an IS21-family transposon. This transposon is present in Prevotella species from more than one geographical location, implying that the mechanism of tetQ spread between oral Prevotella species is highly conserved.

Keywords: Periodontal disease, anaerobe, Bacteroidetes, transposon, IS21, Tn6099, Tn6100, horizontal DNA transfer

INTRODUCTION

The genus Prevotella is composed of obligately anaerobic bacteria associated with the human alimentary tract, as well as the bovine rumen [1]. Prevotella intermedia and Prevotella nigrescens are black-pigmented anaerobic microorganisms commonly found in human dental plaque, and are associated with the development of gingivitis and periodontal disease [2–5]. In addition, oral Prevotella species are common opportunistic pathogens in soft tissue infections of the head and neck [6–9].

Prevotella species are members of phylum Bacteroidetes, and thus are close taxonomic relatives with the oral pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis and the intestinal Bacteroides species [10]. The Bacteroides are well characterized genetically, and they transfer DNA to other bacterial species in the intestine [11]. Studies on gene transfer in these organisms have revealed a multitude of genetic elements, primarily transposons, which can be conjugally transferred [12, 13]. The primary transferable elements identified in the genera Bacteroides are the large (> 60 kb) conjugative transposons (CTns), which are frequently associated with tetracycline resistance, most commonly tetQ, a ribosomal protection gene [14].

TetQ genes similar to those identified in Bacteroides have been found in Prevotella and Porphyromonas species [15–17]. The tetQ gene cloned from one Prevotella nigrescens clinical isolate was nearly identical in sequence to tetQ from a conjugative transposon identified in Bacteroides fragilis [18]. Tetracycline resistant clinical isolates of Prevotella and Porphyromonas have been shown to transfer tetracycline resistance to other bacterial species by conjugation in vitro [19–21].

The degree to which transposable elements contribute to antibiotic resistance in the oral anaerobe community is unclear. Regional studies indicate that there is a great deal of variability in antibiotic resistance frequencies in these bacteria [22]. A study in Spain found that 4% of P. intermedia isolates were resistant to tetracycline [23], while other studies have shown resistance levels as high as 26% [24–27]. As with other medically relevant bacteria, it is likely that selective pressure in the form of antibiotic therapy is driving the development of more resistant organisms in the oral cavity.

Intestinal bacteria are inherently under high levels of antibiotic selective pressure. It has been proposed that these commensal organisms drive the evolution of mobile resistance elements and subsequently transmit them to other more pathogenic bacterial species [28]. While we can hypothesize that oral members of phylum Bacteroidetes are similar to the intestinal species in their genetic systems, no advanced genetic analysis of oral mobile elements has been attempted. In this study, we described our genetic analysis of mobile tetQ elements in oral Prevotella species. Our results indicate that the mobile elements encoding tetQ in oral species are distinct in size and gene content from those found in the Bacteroides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and Growth Conditions

Prevotella clinical isolates (Table 1) were grown in Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB) supplemented with 7.g μM hemin and 3 μM menadione. TSB blood agar plates were made with the addition of 5% sheep’s blood and 1.5% agarose. Prevotella strains were grown anaerobically at 37° C in a Coy anaerobic chamber under 86% nitrogen: 10% carbon dioxide: 4% hydrogen. Selection for antibiotic resistant Prevotella was with 10 μg/ml erythromycin, or 5 μg/ml tetracycline. Dual resistance was selected on 10μg/ml erythromycin and 1μg/ml tetracycline. Select Prevotella strains were made rifampin resistant (MIC> 30 μg/ml) by serial passage on increasing concentrations of the antibiotic. E. coli strains DH5α, S17-1, and STBL-4 (Invitrogen) were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) media supplemented as needed with ampicillin (100 μg/ml).

Table 1.

Bacterial Strains

| Bacterial species | Strain | Country of Origin | Antibiotic resistance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevotella nigrescens | PDRC-11 | Florida, United States | TcR | [18] |

| “ | PDRC-22B | Florida, United States | TcR | [18] |

| “ | VPI-8944 (ATCC 33563) | Virginia, United States | none | [40] |

| “ | Pn28, Pn29, Pn32, Pn34 | Osaka, Japan | TcR | [36] |

| P. denticola | Osaka | Osaka, Japan | TcR | [36] |

| P. intermedia | Pi17 | Osaka, Japan | none | [36] |

| “ | MRS1 | Brazil | TcR | This study |

Construction of a tetQ Mobile Element Capture Plasmid

A transposon capture strategy for Prevotella was designed utilizing plasmid pFD665, a Bacteroides-E. coli suicide vector containing an E. coli pSC101 plasmid origin of replication and RK2 origin of transfer, and an ermF selectable marker for expression in members of the Bacteroidetes [29]. pFD665 replicates as a low-copy number plasmid in E. coli, and must integrate via homologous recombination into the chromosome to be maintained in a Bacteroidetes recipient. For homologous recombination into Prevotella recipients containing the tetQ gene, PCR primers 5′-GGGAAGGCGGTACCTCTCCTTAACGTACG-3′ and 5′-GGGAAGGCGGATCCAATGCTTCTATCTCC-3′ were used to amplify a 2.6 kb fragment containing the tetQ gene. The primers contain KpnI and BamHI restriction sites at the 5′ ends, and the resulting PCR fragment was digested and cloned into the corresponding sites in pFD665, resulting in plasmid pFD665(tetQ) (Figure 1A). pFD665(tetQ) was subsequently mobilized from E. coli strain S17-1 into a Prevotella tetQ+ recipient, and stable integration of the suicide vector into the recipient chromosome (via tetQ homology) was selected for by erythromycin resistance (Figure 1B). The resulting plasmid-transposon chimera was recovered in E. coli, using the Prevotella TcrEmr strain as a donor in DNA conjugation mixes with E. coli recipient strain STBL4. Recipients containing the pFD665(Strain) plasmid were selected on LB media with 100μg/ml ampicillin. The transposon capture strategy was utilized to recover mobile elements containing tetQ from clinical isolates P. nigrescens PDRC11 and PDRC22B (Table 1).

Figure 1. Transposon Capture Method. 1A.

E. coli-Prevotella suicide vector pFD665, with 2.3 kb tetQ gene. Genes functional in Prevotella are shown in light gray, those functional in E. coli are shown in dark gray. The origin of transfer is shown in black. 1B. Transposon capture is mediated by homologous recombination of pFD665(tetQ) (light gray) into the integrated tetQ transposon (black). 1C. Restriction digest of captured tetQ transposon in pFD665.

Prevotella DNA conjugation

Plasmid pFD665(tetQ) was conjugated from E. coli S17-1 donors to Prevotella recipients by mixing log phase cultures at ratios of 1 donor to 100 recipients, pelleting the mixed cultures and resuspending the cells in 50 ul TSB, and incubating the bacterial pellets overnight on pre-reduced blood agar plates in a candle jar at 37°C. Prevotella recipients were selected by incubating 7 to 10 days anaerobically on TSB blood agar containing 100 μg/ml gentamicin, and 10 μg/ml erythromycin. Plasmid conjugal transfers from Prevotella donors to E. coli recipients were similar to E. coli to Prevotella transfers, except the mating pellet was incubated on pre-reduced TSB blood agar plates anaerobically overnight, and E. coli recipients were selected aerobically on LB media with 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Prevotella to Prevotella matings were performed with equal ratios of bacterial strains, and mating mixtures were incubated 24 hours anaerobically at 37°C. Conjugation efficiencies were calculated by dividing the number of transconjugants obtained by the number of input donor cells. Controls for DNA exchange by transformation were Prevotella heat killed donors mixed with viable Prevotella recipients incubated anaerobicallly overnight. Controls were negative for all donor strains tested.

Molecular biology

DNA cloning, sequencing, PCR amplification, Southern blotting, E. coli plasmid purification, and other common molecular biology techniques were carried out by standard procedures [30]. E. coli plasmid purification for DNA sequencing was done using the QiaPrep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen). DNA sequencing was performed by the University of Florida Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research Sequencing Core (Gainesville, FL), and by SeqWright DNA Technology Services (Houston, TX). Sequence assembly, DNA and protein analysis was done with CLC Combined Workbench, v3 (CLC bio). Total DNA was purified from Prevotella using the Promega Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit, with further purification by phenol/chloroform extraction if necessary. Southern hybridizations employed the Amersham AlkPhos Direct Labelling and Detection System (GE Healthcare).

RESULTS

TetQ transposon capture

Prevotella nigrescens strains PDRC11 and PDRC22B were originally isolated from diseased sites in patients with refractory periodontitis; the PDRC11 strain is resistant to penicillins and tetracyclines, and can transfer these resistances to other bacteria in conjugation assays (LaCroix & Walker, 1996). The gene conferring tetracycline resistance in PDRC11 was cloned and determined by DNA sequence analysis to be tetQ, and was found to be chromosomally-encoded [18]. Using the sequence data available for PDRC11 tetQ, we designed a transposon capture strategy utilizing plasmid pFD665, a Bacteroides-E. coli shuttle vector originally used to clone and sequence a conjugative transposon (cTn341) from B. fragilis strain 341 [29]. The strategy used to capture the tetQ mobile element is described in the Materials and Methods, and illustrated in Figure 1B.

Our original approach was to mobilize pFD665(tetQ) directly into PDRC11, however we were unable to obtain any transconjugants from repeated attempts at this mating. Introduction of foreign DNA into Prevotella species is notoriously difficult and some Prevotella are known to produce extracellular endonucleases and restriction/modification systems [31, 32]. P. nigrescens VPI-8944 has been shown to reliably accept plasmid DNA from E. coli [33], thus we modified our strategy to utilize this genetically tractable strain. VPI-8944 was made rifampicin resistant (Rfr ; MIC> 30μg/ml) by serial passage. The VPI-8944 Rfr strain was then utilized as a recipient in a mating with PDRC11 as the donor, and VPI-8944 TcrRfr transconjugants were obtained at a frequency of 8.12 × 10−5. The presence of the tetQ gene in the VPI-8944 TcrRfr transconjugants was confirmed by PCR.

The VPI-8944 TcrRfr strain was then used as the recipient for the pFD665(tetQ) plasmid, and Emr transconjugants were obtained at a frequency of 2.2 ×10−8. Insertion of the pFD665(tetQ) plasmid into the tetQ gene of the VPI-8944 TcrRfrEmr transconjugants was confirmed by Southern blot. The VPI-8944 TcrRfrEmr strain was then used as a donor in a mating with E. coli STBL4 as the recipient, to recover the tetQ mobile element in plasmid form. The conjugation frequency for this transfer was 3.3 × 10−8. After successful capture of the P. nigrescens PDRC11 mobile element, we utilized the same strategy to capture the element from P. nigrescens PDRC22B.

Genetic Analysis of the Captured Transposon

Plasmid DNA from an E. coli Apr transconjugant was purified and analyzed by restriction digest and agarose gel electrophoresis (Figure 1C). Comparison of the supercoiled pFD665(tetQ) vector to the vector recovered from the VPI-8944 TcrRfrEmr strain, pFD665(PDRC11), illustrates a significant increase in size in the recovered plasmid, as would result from capture of a mobile Prevotella DNA element. The original and recovered plasmids were further compared by restriction digest with EcoRI, HindIII, and PstI. There are no PstI sites in pFD665(tetQ), and one each of EcoRI and HindIII (Figure 1A). The recovered plasmid, pFD665(PDRC11), contained one PstI site, and two each for EcoRI and HindIII. Comparison of restriction fragment sizes from the original and recovered plasmids indicated a captured PDRC11 DNA fragment of approximately 7.5 kb. Similar analysis of the recovered pFD665(PDRC22B) plasmid indicated capture of a slightly smaller DNA fragment (approximately 6 kb; data not shown.)

DNA Sequence Analysis of the Captured Transposon

The pFD665(PDRC11) recovered plasmid contains a duplication of the tetQ gene (Figure 1B), making it difficult to sequence the captured element directly in this vector. We sub-cloned the EcoRI fragment representing the captured fragment into pUC18, and used M13 forward and reverse primers to initiate first and second strand sequencing of the mobile element by primer walking. Once a draft of the captured sequence was complete, we designed PCR primers to amplify the mobile element directly from the original host strain, P. nigrescens PDRC11. These PCR fragments were sequenced directly, to eliminate inclusion of potential DNA mutations or deletions acquired during transfer of the element into P. nigrescens VPI-8894 and E. coli STBL4. The final mobile element sequence results from a minimum of three-fold coverage. The PDRC22B captured DNA fragment was sequenced using the same strategy. A Tn number was assigned for each sequenced element using the Tn number registry at the Eastman Dental Institute http://www.ucl.ac.uk/eastman/tn/index.php. The final sequence data for these elements is archived under the GenBank Accession numbers HM561907 for the PDRC11 element (Tn6099) and HM561908 for PDRC22B (Tn6100).

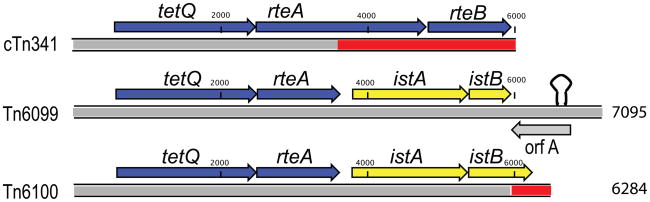

The final length of the PDRC11 mobile element Tn6099 is 7095 bp, and the element encodes five putative proteins of greater than 50 amino acids (Figure 2). The DNA sequence encompassing the first two open reading frames has the most extensive homology (94% over 3590 bp) to the tetQ-rteAB operon of the conjugative transposons found in the intestinal Bacteroides. Alignment of the PDRC11 sequence with the closest homolog, from cTn341 [29], reveals that the rteA open reading frame in PDRC11 is truncated, and the rteB gene is absent (Figure 2). In Tn6099, the 3′ region of rteA is replaced with two open reading frames encoding proteins with homology to the IS21 transposase IstA and accessory protein IstB [34]. The putative IstA protein contains an DDE motif, commonly found in transposase enzymes, and the IstB protein contains a DEAD/DEAH box helicase motif [35]. Althought the IstB protein from Tn6099 is truncated relative to IstB of Tn6100, the DEAD helicase motif is intact in both proteins. Downstream of istB is a fifth open reading frame, which has no homology at the DNA or protein level to sequences found in GenBank. This open reading frame is designated orfA, and is found on the reverse strand relative to the other four genes. Secondary structure analysis of Tn6099 reveals a large multiloop hairpin structure encompassing a 1 kb region; this hairpin is downstream of istB, with a ΔG = −270.1kcal/mol. The sequenced mobile element Tn6100 is identical in sequence to Tn6099 over the first 5.7 kB, but the 1 kb region of secondary structure found in Tn6099 is absent from Tn6100, and instead a 308 bp region containing a 3′ continuation of the istB open reading frame is present.

Figure 2. DNA sequence Alignment of Prevotella Captured Elements with a Bacteroides tetQ operon.

Homologous DNA is represented in grey, non-homologous DNA in white. The PDRC11 transposon sequence Tn6099 is the reference. The region of strong secondary structure in Tn6099 is represented by a hairpin.

Detection of tetQ-istA-istB in Prevotella clinical isolates

Clinical strains P. nigrescens PDRC11 and P. nigrescens PDRC22B are from the collection of the Periodontal Disease Research Center at the University of Florida. We wished to determine if the association of tetQ with istAB transposition genes exists in isolates of Prevotella from independent sources. We screened a collection of Prevotella isolates originating from Osaka, Japan for tetracycline resistance by growth on media with 1 μg/ml Tc, and identified five strains of P. nigrescens and one strain of P. denticola that were tetracycline resistant and contained the tetQ gene (Figure 3)[36]. We also acquired a tetQ positive P. intermedia strain from Brazil (strain MRS1). Using PCR, we tested genomic DNA from each strain for the presence of istA and istB, and for linkage between the tetQ-rteA genes and the istA-istB genes. All five isolates from the Osaka collection were positive for istAB and for rteA-istA, and the MRS1 isolate was weakly positive for both bands.

Figure 3. Detection of tetQ elements in diverse isolates of Prevotella.

3A. Location and expected size of PCR products based on the PDRC11 tetQ element sequence. 3B. PCR products from Prevotella strains isolated in Japan (Pi17, Pn28,Pn29,Pn32,Pn34,Pd-Osaka), Brazil (MRS1), and Florida (PDRC11, PDRC22B).

Horizontal DNA transfer of tetQ from Prevotella clinical isolates

In our tetQ mobile element capture strategy, we successfully utilized P. nigrescens VPI-8944 as a recipient strain in matings with P. nigrescens PDRC11 and 22B donors. We wished to determine if the Prevotella isolates from Osaka and Brazil are also able to mobilize tetQ by horizontal DNA transfer. Conjugation assays revealed that all istAB positive strains can mediate tetQ transfer to P. nigrescens VPI-8944; the P. intermedia MRS1 isolate, containing a very weak istAB band, was not (Table 2). Notably, the highest rates of transfer were from the P. denticola Osaka donor and P. nigrescens PDRC22B, which were not statistically different. (P value = 0.68).

Table 2.

tetQ Conjugation Efficiencies from Prevotella clinical isolates into recipient P. nigrescens VPI-8944.

| Donor Strain | Conjugation Efficiency | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| P. nigrescens 28 | 4.34E-07 | 1.11E-07 |

| P. nigrescens 29 | 1.63E-06 | 1.58E-06 |

| P. nigrescens 32 | 6.65E-08 | 9.40E-08 |

| P. denticola Osaka | 1.18E-04 | 1.47E-04 |

| P. intermedia MRS1 | <10−9 | ND |

| P. nigrescens PDRC-22B | 3.56E-04 | 5.01E-04 |

| P. nigrescens PDCR-11 | 8.12E-05 | 1.11E-05 |

Genetic Analysis of P. nigrescens VPI-8944 tetQ+ Transconjugants

Genomic DNA from P. nigrescens PDRC11 and a P. nigrescens VPI-8944 transconjugant from a PDRC11 mating were analyzed by Southern blot, using the entire Tn6099 element as the probe (Figure 4A). Genomic DNA was digested with AvaI (one site), XbaI (5 sites), or SphI (0 sites); the relative locations of the restriction sites are shown in Figure 4B. The AvaI digest results in a strong band just under 8 kb in size, and one weak band over 10 kb. We expect two bands from a linear, integrated mobile element; one band has a much stronger signal than the other indicating that the AvaI site is very close to one end of the integrated element. In the XbaI digest, we expect six bands from the integrated element; the 0.4 kb, 0.9 kb, 1.0 kb, and 1.8 kb bands are present as anticipated. The 2.8 kb band is missing, and replaced with a strong band at approximately 5 kb, and a weak band at approximately 3.5 kb. This indicates that the 2.8 kb XbaI fragment contains the integration site or “ends” of the transposable element, which is consistent with the AvaI results. This places the putative transposon ends near the 3′ end of the istB gene and the stem-loop structure; this region is represented in the Figure 4B restriction map as a dot. To confirm if this site represents the integration region for Tn6099, we used PCR to test genomic DNA from P. nigrescens PDRC11 for the presence of an intact region of DNA between istB and tetQ (Figure 4C). The region between istB and tetQ is not intact in genomic DNA, confirming that this is the region containing the integrating ends of the transposable element.

Figure 4. Analysis of Prevotella mobile element insertion.

4A Southern blot of genomic DNA from P. nigrescens PDRC11 and its transconjugant offspring P. nigrescens VPI-8894. Genomic DNA was digested with AvaI (A), XbaI (X), and SphI (S). 4B. XbaI and AvaI restriction map of PDRC11 tetQ element Tn6099, and PCR fragments amplified from genomic DNA. 4C. PCR results from genomic amplification of strain PDRC11. 4D. Southern blot of tetQ in BamHI restricted genomic DNA from transconjugants of P. nigrescens VPI-8894. Transconjugant donors: lane 1, P. nigrescens strain 28; lane 2, P. nigrescens strain 29; lane 3, P. nigrescens strain 32; lane 4, P. denticola Osaka; lane 5, P. nigrescens strain 22B; Controls: lane 6, P. nigrescens 22B; lane 7, P. nigrescens VPI-8944.

P. nigrescens VPI-8944 transconjugants from matings with five different donors were analyzed to confirm the presence of tetQ in the chromosome, and to determine if the mobile elements from different strains utilized the same insertion site. Genomic DNA from select transconjugants was digested with BamHI, which has no sites in Tn6099 or Tn6100, and post-electrophoresis was analyzed by Southern blot, using the tetQ gene as the probe (Figure 4D). Transconjugants from all 5 donors produced single bands between 12 and 13 kb ; the P. nigrescens 8944 recipient control had no band. Thus the tetQ mobile element in each of the donor strains also lack BamHI sites, consistent with the sequenced elements. Bands from P. nigrescens strains 28, 29, and 32 are the same size, indicating that these three tetQ mobile elements insert into the same site. The hybridizing fragments from the P. denticola and P. nigrescens 22B donors are slightly larger; these elements either insert in a different site, or these elements may be slightly larger than those found in P. nigrescens strains 28, 29, and 32.

DISCUSSION

Plaque biofilms offer an excellent opportunity to study gene transfer in a disease associated bacterial population. Interspecies genetic exchange has the potential to transfer antibiotic resistance genes, which may result in infections resistant to therapy. Additionally, members of the oral flora may acquire or transfer antibiotic resistance to other bacteria that reside elsewhere in the human flora. Many Prevotella strains contain the tetQ tetracycline resistance gene, which is highly similar to the tetQ gene found conjugative transposons in intestinal species of Bacteroides.

Our capture and genetic analysis of two tetQ mobile elements from P. nigrescens reveals these oral transposable elements to be distinct from the tetQ carrying Bacteroides elements in size, and in gene composition. The Bacteroides conjugative transposons are large (40–60 kb); encode multiple genes required for formation of a conjugal pore and DNA mobilization (tra A-Q; mob); and mediate integration into the bacterial chromosome using integrase-family enzymes and a site-specific recombination mechanism [37]. The elements identified in Prevotella are relatively small (6–7 kb), do not encode a conjugal transfer apparatus, and appear to utilize an IS21-family transposase enzyme. The lack of an obvious origin of transfer or mobilization protein leaves the mechanism of horizontal transfer for the Prevotella elements in question. The genome sequence of P. intermedia strain 17 (TIGR; Rockville, MD, USA) contains a locus with high homology to the transfer genes found in the Bacteroides conjugative transposons; the Prevotella tetQ elements may thus be more similar in mechanism to the mobilizable transposons of the Bacteroides and utilize a DNA transfer apparatus provided by the host cell or a co-resident mobile element [12, 13]. In Porphyromonas gingivalis, a member of the oral Bacteroidetes, chromosomal DNA undergoes horizontal transfer [38]; it is possible that the Prevotella tetQ transposons are horizontally transferred as part of genomic DNA and subsequently transpose into the recipient genome, or are incorporated as part of the transferred genomic DNA by homologous recombination. Regardless of the detailed mechanism of horizontal transfer, it is clear that the Prevotella mobile tetQ elements are genetically and functionally distinct from those found in the Bacteroides.

The clear DNA homology breakpoints in the Tn6099 sequence at genes rteA (compared to cTn341) and istB (compared to Tn6100) imply a modular or cassette assembly of the mobile element. In the Bacteroides, RteA and RteB are two component signal transduction molecules that regulate DNA transfer in response to tetracycline; these genes are located downstream and in an operon with tetQ [39]. In the Prevotella elements, rteA is not intact and rteB is absent, implying that the tetQ gene was acquired as the only functional gene from a tetQ-rteA-rteB operon. The istB gene is truncated in Tn6099 compared to Tn6100. The istB predicted function is as a transposition accessory protein, and as such may not be required for transposition; however, the DEAD box motif found in the protein is intact. The Tn6099 istB 3′ end is replaced with a region of strong secondary structure; in Tn6099 this region also contains the ends of the transposon. GC content analysis of the Prevotella tetQ elements indicates that the overall GC content is 45%, similar to the expected 43% GC content of Prevotella genome sequences.

Prevotella clinical isolates from other geographical locations also contained tetQ, and five out of six contained the istAB genes in the same distance and orientation relative to tetQ as the PDRC mobile elements. The istAB positive strains were capable of mediating tetQ transfer to P. nigrescens VPI-8944, the P. intermedia MRS1 isolate was not; this implies that tetQ association with the istAB genes is important for transfer. P. intermedia MRS1 genomic DNA was weakly amplified by the istAB and tetQ-istA primers; this strain may have a diverged and/or non-functional version of the Prevotella tetQ transposon. Horizontal DNA transfer normally occurs at the highest frequencies between bacteria of the same species, however in this study P. denticola donated tetQ to a P. nigrescens recipient at conjugation frequencies comparable to (or higher than) P. nigrescens donors. Thus the ability of the donor to mobilize these Prevotella elements, along with inter-species restriction/modification compatibility, may be a determining factor in successful tetQ transfer to a recipient.

These studies indicate that the mechanism of tetQ spread between oral Prevotella species is conserved, and these bacteria use a transposon with a DNA sequence unique to the Prevotella. TetQ genes were found in Prevotella clinical isolates from diverse geographical locations, and the mobile elements all appear to be associated with an IS21-like transposon. The intestinal Bacteroides may act as a reservoir for the tetQ gene, but the oral Prevotella have evidently incorporated this gene into their own mobilome, based on an IS21-family transposon. The horizontal DNA transfer apparatus that mediates the spread of these tetQ transposons has yet to be identified.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ann Progulske-Fox for the gift of strain P. nigrescens VPI-8944, and Regina Simionato for the gift of strain P. intermedia MRS1. Support for this research was provided by grant DE016562 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research to GDT.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Avgustin G, Ramsak A, Peterka M. Systematics and evolution of ruminal species of the genus. Prevotella. 2001;46:40–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02825882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Socransky SS, Smith C, Haffajee AD. Subgingival microbial profiles in refractory periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:260–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teanpaisan R, Douglas CW, Walsh TF. Characterisation of black-pigmented anaerobes isolated from diseased and healthy periodontal sites. Journal of Periodontal Research. 1995;30:245–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1995.tb02129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore WE, Moore LV. The bacteria of periodontal diseases. Periodontol. 1994;5:66–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1994.tb00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Listgarten MA, Lai CH, Young V. Microbial composition and pattern of antibiotic resistance in subgingival microbial samples from patients with refractory periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1993;64:155–61. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.3.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gendron R, Grenier D, Maheu-Robert L. The oral cavity as a reservoir of bacterial pathogens for focal infections. Microbes and Infection. 2000;2:897–906. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00391-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bae KS, Baumgartner JC, Shearer TR, David LL. Occurrence of Prevotella nigrescens and Prevotella intermedia in infections of endodontic origin. Journal of Endodontics. 1997;23:620–3. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grollier G, Dore P, Robert R, Ingrand P, Grejon C, Fauchere JL. Antibody response to Prevotella spp. in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory. Immunology. 1996;3:61–5. doi: 10.1128/cdli.3.1.61-65.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Botha SJ, Senekal R, Steyn PL, Coetzee WJ. Anaerobic bacteria in orofacial abscesses. J Dent Assoc S Afr. 1993;48:445–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paster B, Dewhirst F, Olsen I, Fraser G. Phylogeny of Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Porphyromonas spp. and related bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:725–32. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.725-732.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shoemaker NB, Vlamakis H, Hayes K, Salyers AA. Evidence for extensive resistance gene transfer among Bacteroides spp. and among Bacteroides and other genera in the human colon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:561–8. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.561-568.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith CJ, Tribble GD, Bayley DP. Genetic elements of Bacteroides species: a moving story. Plasmid. 1998;40:12–29. doi: 10.1006/plas.1998.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salyers AA, Shoemaker NB, Li LY. In the driver’s seat: the Bacteroides conjugative transposons and the elements they mobilize. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5727–31. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5727-5731.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikolich MP, Shoemaker NB, Salyers AA. A Bacteroides tetracycline resistance gene represents a new class of ribosome protection tetracycline resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1005–12. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.5.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacroix JM, Walker CB. Detection and prevalence of the tetracycline resistance determinant Tet Q in the microbiota associated with adult periodontitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1996;11:282–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1996.tb00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olsvik B, Olsen I, Tenover FC. The tet(Q) gene in bacteria isolated from patients with refractory periodontal disease. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1994;9:251–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1994.tb00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olsvik B, Tenover FC. Tetracycline resistance in periodontal pathogens. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16 (Suppl 4):S310–3. doi: 10.1093/clinids/16.supplement_4.s310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker CB, Bueno LC. Antibiotic resistance in an oral isolate of Prevotella intermedia. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25 (Suppl 2):S281–3. doi: 10.1086/516222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung WO, Young K, Leng Z, Roberts MC. Mobile elements carrying ermF and tetQ genes in gram-positive and gram- negative bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;44:329–35. doi: 10.1093/jac/44.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guiney DG, Hasegawa P. Transfer of conjugal elements in oral black-pigmented Bacteroides (Prevotella) spp. involves DNA rearrangements. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4853–5. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4853-4855.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guiney DG, Bouic K. Detection of conjugal transfer systems in oral, black-pigmented Bacteroides spp. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:495–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.495-497.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falagas ME, Siakavellas E. Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Porphyromonas species: a review of antibiotic resistance and therapeutic options. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;15:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(99)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andres MT, Chung WO, Roberts MC, Fierro JF. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, and Prevotella nigrescens spp. isolated in Spain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3022–3. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.11.3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Winkelhoff AJ, Herrera D, Oteo A, Sanz M. Antimicrobial profiles of periodontal pathogens isolated from periodontitis patients in The Netherlands and Spain. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:893–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maestre JR, Bascones A, Sanchez P, Matesanz P, Aguilar L, Gimenez MJ, et al. Odontogenic bacteria in periodontal disease and resistance patterns to common antibiotics used as treatment and prophylaxis in odontology in Spain. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2007;20:61–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulik EM, Lenkeit K, Chenaux S, Meyer J. Antimicrobial susceptibility of periodontopathogenic bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:1087–91. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serrano C, Torres N, Valdivieso C, Castano C, Barrera M, Cabrales A. Antibiotic resistance of periodontal pathogens obtained from frequent antibiotic users. Acta Odontol Latinoam. 2009;22:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salyers AA, Shoemaker NB. Resistance gene transfer in anaerobes: new insights, new problems. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23 (Suppl 1):S36–43. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.supplement_1.s36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith CJ, Parker AC, Bacic M. Analysis of a Bacteroides conjugative transposon using a novel “targeted capture” model system. Plasmid. 2001;46:47–56. doi: 10.1006/plas.2001.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular cloning : a laboratory manual. 3. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Accetto T, Peterka M, Avgustin G. Type II restriction modification systems of Prevotella bryantii TC1–1 and Prevotella ruminicola 23 strains and their effect on the efficiency of DNA introduction via electroporation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;247:177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porschen RK, Sonntag S. Extracellular deoxyribonuclease production by anaerobic bacteria. Appl Microbiol. 1974;27:1031–3. doi: 10.1128/am.27.6.1031-1033.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Progulske-Fox A, Oberste A, Drummond C, McArthur WP. Transfer of plasmid pE5–2 from Escherichia coli to Bacteroides gingivalis and B. intermedius. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1989;4:132–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1989.tb00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berger B, Haas D. Transposase and cointegrase: specialized transposition proteins of the bacterial insertion sequence IS21 and related elements. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:403–19. doi: 10.1007/PL00000866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finn RD, Tate J, Mistry J, Coggill PC, Sammut SJ, Hotz HR, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D281–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukushima H, Moroi H, Inoue J, Onoe T, Ezaki T, Yabuuchi E, et al. Phenotypic characteristics and DNA relatedness in Prevotella intermedia and similar organisms. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1992;7:60–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1992.tb00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Churchward G. Conjugative Transposons and Related Mobile Elements. In: Craig NL, Craigie R, Gellert M, Lambowitz AM, editors. Mobile DNA II. Washington DC: ASM Press; 2002. pp. 177–91. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tribble GD, Lamont GJ, Progulske-Fox A, Lamont RJ. Conjugal transfer of chromosomal DNA contributes to genetic variation in the oral pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:6382–8. doi: 10.1128/JB.00460-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevens AM, Sanders JM, Shoemaker NB, Salyers AA. Genes involved in production of plasmidlike forms by a Bacteroides conjugal chromosomal element share amino acid homology with two- component regulatory systems. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2935–42. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.9.2935-2942.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah HN, Gharbia SE. Biochemical and chemical studies on strains designated Prevotella intermedia and proposal of a new pigmented species, Prevotella nigrescens sp. nov Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:542–6. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-4-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]