Abstract

Hepatic hemangiomas are congenital vascular malformations, considered the most common benign mesenchymal hepatic tumors, composed of masses of blood vessels that are atypical or irregular in arrangement and size. Hepatic hemangiomas can be divided into two major groups: capillary hemangiomas and cavernous hemangiomas These tumors most frequently affect females (80%) and adults in their fourth and fifth decades of life. Most cases are asymptomatic although a few patients may present with a wide variety of clinical symptoms, with spontaneous or traumatic rupture being the most severe complication. In cases of spontaneous rupture, clinical manifestations consist of sudden abdominal pain, and anemia secondary to a haemoperitoneum. Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy can also occur. Haemodynamic instability and signs of hypovolemic shock appear in about one third of cases. As the size of the hemangioma increases, so does the chance of rupture. Imaging studies used in the diagnosis of hepatic hemangiomas include ultrasonography, dynamic contrast-enchanced computed tomography scanning, magnetic resonance imaging, hepatic arteriography, digital subtraction angiography, and nuclear medicine studies. In most cases hepatic hemangiomas are asymptomatic and should be followed up by means of periodic radiological examination. Surgery should be restricted to specific situations. Absolute indications for surgery are spontaneous or traumatic rupture with hemoperitoneum, intratumoral bleeding and consumptive coagulopathy (Kassabach-Merrit syndrome). In a patient presenting with acute abdominal pain due to unknown abdominal disease, spontaneous rupture of a hepatic tumor such as a hemangioma should be considered as a rare differential diagnosis.

Keywords: Hepatic hemangioma, Giant hepatic hemangioma, Liver tumor, Spontaneous rupture, Surgery

INTRODUCTION

Hepatic hemangiomas are congenital vascular malformations, considered the most common benign mesenchymal hepatic tumors, composed of masses of blood vessels that are atypical or irregular in arrangement and size[1]. Malignant transformation is extremely rare. They are often diagnosed as incidental findings on imaging studies of the abdomen during exploratory surgeries[2]. It is estimated that about 20% of the general population present hepatic hemangiomas, and the prevalence in autopsy studies ranges between 0.4%-7.4%[3-5]. These tumors most frequently affect females (80%) and adults in their fourth and fifth decades of life[1,6,7].

The hepatic hemangiomas are often solitary although multiple lesions may be present in both hepatic lobes in up to 40% of the patients. Their size varies from a few millimeters to over 20 cm. Those lesions larger than 5 cm are reported as giant hemangiomas. Most cases are asymptomatic (especially when smaller than 4 cm), but a few patients may present a wide variety of clinical symptoms with spontaneous or traumatic rupture being the most severe complication. This has a catastrophic outcome if not promptly managed[3], and is the reason why correct diagnosis and management are extremely important[5]. A study by Jain et al indicated that the operative mortality rate of ruptured lesions is around 36.5%[1].

The first case of spontaneous rupture of a hepatic hemangioma was described by Van Haefen in an autopsy in 1898[8]. In 1961, Swell and Weiss reviewed 12 cases of spontaneous rupture of hemangiomas from literature and reported the mortality rate to be as high as 75%[3].

Bleeding of spontaneous rupture is a severe complication in liver diseases, as its clinical signs are not usually specific. The risk of rupture is generally considered to be one reason for performing surgical resection of the hemangioma[9].

CLASSIFICATION

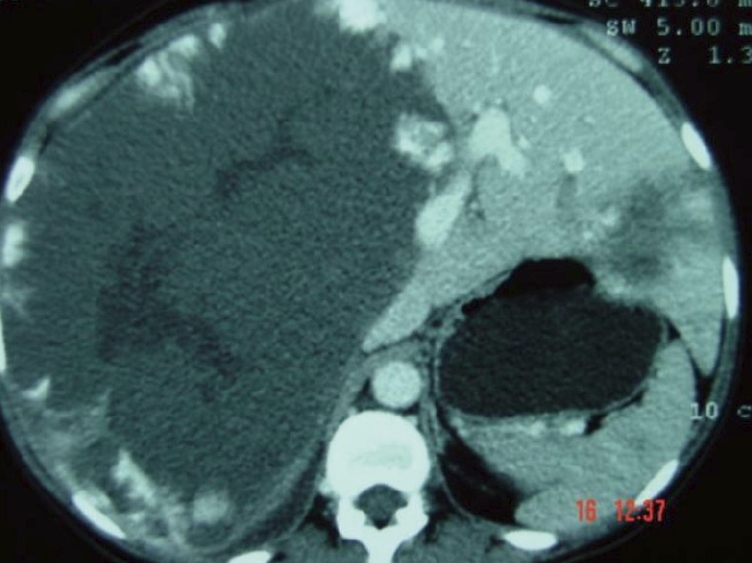

Hepatic hemangiomas are classified as primary benign vascular tumors of the liver, and can be divided into two major groups: (1) capillary hemangiomas, generally peripheral, small, and sometimes multiple; and (2) cavernous hemangiomas, which are rarer and larger, also known as giant hemangiomas when larger than 4-5 cm. Occasionally these can reach up to 20-30 cm[7], as seen in Figures 1 and 2.

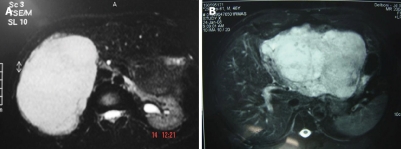

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan of a huge liver cavernous hemangioma compromising the right liver lobe.

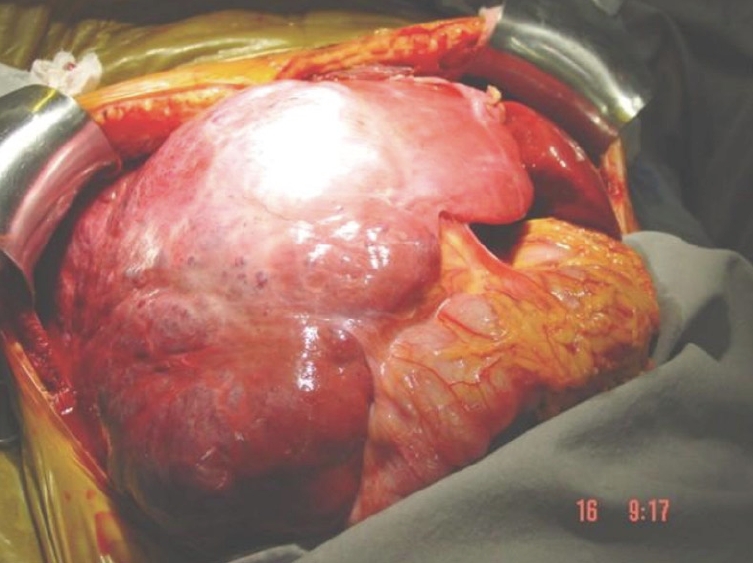

Figure 2.

Intraoperative finding of a huge liver cavernous hemangioma compromising the right liver lobe.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

According to the case report and literature review by Vokaer et al[8], since 1898 when Van Haefen described the first case of spontaneous rupture of a liver hemangioma, only 33 cases of ruptured hemangioma in adults have been reported in the literature. Spontaneous rupture of this tumor is an uncommon complication, representing 1%-4% in Jain’s case series (spontaneous rupture with hemoperitoneum)[3] and 2.9% in the study of Chen et al[5] (a study of 70 cases admitted from 1992-2001 with spontaneous liver rupture including primary liver cancer, cirrhosis, liver adenoma, secondary liver cancer and liver hemangioma as causes of rupture). Treatment methods for spontaneous liver rupture in these 70 patients were suture in 17 (24.3%), packing in 7 (10%), ligation of hepatic artery in 23 (32.9%), hepatic artery chemoembolization in 2 (2.9%) and hepatic partial resection in 40 (57.1%)[5]. Jain et al described a mortality rate ranging from 60% to 75% for spontaneous rupture with an operative mortality rate from this complication of 36.4%[3].

Yamamoto et al researched 28 cases of spontaneous rupture of hepatic hemangiomas (19 adults and 9 children), and reported that surgical treatment was carried out on 20 patients, of whom only 5 survived. The ruptured tumors ranged in size from 3 to 25 cm, many of them located on the surface of the liver[10].

Corigliano et al reviewed 27 of 32 cases reported in the literature up to 2003, and indicated that 16 (84.2%) of 19 tumors were giant hemangiomas (range 6-25). Twenty-two (95.7%) underwent surgery (13 resections, 5 sutures, 4 tamponade). Three (23%) of 13 resected patients had died. Among the sutured patients, 2 died (40%) as well as 3 (75%) of the 4 patients who underwent tamponade. The mortality rate of all surgery patients researched by Corigliano et al[11] was 36.4% (8/22), as noted by Jain et al in their literature review.

ETIOLOGY

Some authors believe that hepatic hemangiomas are congenital hamartomatous lesions of the liver that grow silently over the years[12]. No genetic or familial mode of inheritance has been clearly described, although Moser et al reported on a large family of Italian origin in which 3 female patients in 3 successive generations had large symptomatic hepatic hemangiomas[13].

Several pharmacologic agents have been postulated to cause tumor growth. Steroid therapy, estrogen therapy and pregnancy can increase the size of an already existing hemangioma. Experimental studies have revealed that estrogens augment endothelial cell proliferation, migration and organization into capillary-like structures. In vitro, they promote the proliferation of the endothelial cells of the hemangioma and also work synergistically with vascular endothelial growth factor[14]. In another study, Xiao described that hemangiomas have estrogen receptors, an indication that these tumors may be a target tissue for estrogens[15].

Spitzer et al studied prospectively 94 women with hepatic hemangiomas over a period of 7.3 years and noticed an increase in the size of the lesions in women who received hormonal therapy -23% vs 10% in control subjects[16]. Although several possibilities have been described, the exact etiology still remains unknown.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Hepatic hemangiomas are mainly asymptomatic, although they can induce intermittent right upper quadrant pain related to focal necrosis or pain from capsular distension as the tumor grows. Thrombosis, infarction, hemorrhage into the lesion and compression of adjacent structures are other possible causes of pain. Giant hemangiomas can also cause biliary colic, obstructive jaundice, and gastric outlet obstruction[4].

Spontaneous hepatic hemorrhage is an uncommon condition, and in the absence of anticoagulant therapy or trauma, it frequently occurs as a consequence of hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatic adenoma or, in a few cases, of spontaneous rupture of a cavernous hemangioma[17].

In cases where spontaneous rupture occurs, clinical manifestations consist of sudden abdominal pain, and anemia secondary to a hemoperitoneum. Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy can also occur[6,7]. Hemodynamic instability and signs of hypovolemic shock appear in about one third of cases[8]. The global mortality of rupture is approximately 35%, and it seems to be related to the size of the lesions. As the size of the hemangioma increases, so does the chance of rupture[8,9], especially if the tumor is located on the surface of the liver and shows extrahepatic growth. If the patient receives steroid therapy for a coexisting disorder, the chance of rupture is even higher[9].

The clinical presentation of liver hemangioma in pregnancy does not differ from the same mass in a non-pregnant woman. Laboratory studies usually show some an elevation of transaminases, bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase even in asymptomatic cases. The rupture of a small hemangioma may lead to serious intra-abdominal hemorrhage. In fact, liver hemangiomas during pregnancy are potentially serious lesions, especially as their rupture during labor can precipitate an hemorrhagic shock[6] .

DIAGNOSTIC TOOLS

Imaging studies used in the diagnosis of hepatic hemangiomas include ultrasonography, dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scanning, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), hepatic arteriography, digital subtraction angiography, and nuclear medicine studies[1].

Ultrasonography is commonly used as an initial diagnostic tool as it is widely available and inexpensive. Hemangiomas are seen as sharp edged hyperechoic lesions with clear borders (when small, they are strongly hyperechoic) although in cases with hemorrhage, fibrosis and necrosis, their appearance may be different[1,16,18]. The addition of color Doppler provides qualitative and quantitative data and increases the sensitivity and specificity of the test. In general, the finding on ultrasonography of a suspected hemangioma should be diagnostically integrated with CT scan or MRI to ensure a correct diagnosis.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT scanning, especially triple phase CT with delayed imaging, is preferred (Figure 1). In this exam, hemangiomas are typically hypodense on precontrast imaging; in the arterial phase there may be enhancement of the peripheral portions of the lesion while the center of the lesion remains hypodense[1,17]. In cases which may can be diagnosed conclusively by US and CT, MRI may provide more specific diagnostic features (Figures 3A and B), with a sensitivity upwards of 90%[1]. The lesions have markedly high signal intensity on T2 weighted images and a specific dynamic contrast enhancement pattern (in a fashion similar to that seen on CT)[17]. T1-weighted images have low signal density[19,20].

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging of hemangioma. A: Right lobe; B: Left lobe.

Giant cavernous hemangiomas may exhibit internal fluid levels on MRI and CT scan, because of the slow blood flow through the tumor that allows separation of the blood cells.

When hemangiomas are ruptured, radiological findings reveal hemoperitoneum and heterogeneous hepatic mass. Intraperitoneal clots may also be identified near to the site of the bleeding[17].

Nuclear medicine studies include single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) using Tc-99m pertechnetate-labeled RBCs. SPECT is more specific than MRI, but less sensitive. Some authors consider SPECT to be the standard diagnostic tool. However, the test may miss some lesions and it is unfortunately not available at all medical centers[21,22].

Arteriography is an invasive modality that can be useful to diagnose some hepatic hemangiomas that are characterized by early opacification or irregular areas or lakes with persistence of contrast long after arterial emptying. The hemangioma may appear as a C-shaped lesion with an avascular center[1].

In a retrospective study of 27 patients with 35 hemangiomas De Franco et al compared the diagnostic capabilities of ultrasonography, Doppler color ultrasonography, dynamic CT scanning and MRI. The results were as follows: ultrasonography -46% sensitivity; combined color Doppler ultrasonography and B-mode -60% sensitivity; T2-weighted MRI -96% sensitivity; gadolinium enchanced MRI with dynamic CT scanning -100% sensitivity[23].

Diagnostic accuracy diminishes in all imaging modalities when lesions are smaller than 2 cm in diameter. In these cases, MRI and 99mTc-RBC SPECT are the most accurate radiological methods for establishing a diagnosis.

In some cases the hemangioma may be a differential diagnosis of a hepatic mass. Liver biopsy is contraindicated in most cases because of an increased risk of hemorrhage. In cases where a small liver lesion must be differentiated from hepatocellular carcinoma, either percutaneous or laparoscopic liver biopsy may be reasonable. However, over the years, hepatologists and surgeons have been increasingly resistant to biopsy in the vast majority of cases. Biopsy should be used only when radiologic studies and alpha fetoprotein testing are inconclusive.

TREATMENT

The treatment of hepatic hemangioma should be decided based on the size and location of the tumor[9]. Small hemangiomas (< 4 cm) can be managed by observation and as, in most cases, hepatic hemangiomas are asymptomatic they should be followed up by means of periodic radiological examination. Surgery should be restricted to specific situations.

Absolute indications for surgery are spontaneous or traumatic rupture with hemoperitoneum, intratumoral bleeding and consumptive coagulopathy (Kassabach-Merrit syndrome). Rupture of a hemangioma with hemoperitoneum is a dreadful situation and often fatal if not promptly managed. Persistent abdominal pain, obstructive jaundice, portal hypertension, superficial location of tumors larger than five cm with a risk of trauma, pain and uncertain diagnosis are all relative surgical indications[3,4,7]. The proposed surgical procedures for the treatment of liver hemangioma are as follows: (1) anatomic, nonanatomic resection, enucleation (the procedure of choice to treat giant hemangiomas, especially in superficial lesions but should be discouraged for intrahepatic lesions because of large scale bleeding. This procedure has a major advantage when compared to hepatectomy, the greater preservation of the parenchyma), ligation of the hepatic artery (in cases where it is not possible to remove the tumor, but its benefit is suspicious); (2) selective portal vein embolization (reduces the size of the lesion when the tumor is too big to be removed,); and (3) liver transplantation.

Spontaneous rupture of a liver hemangioma is challenging because it is considered a life threatening situation. Conservative treatment runs the risk of hypovolemic shock, and aggressive surgical treatment is associated with a high mortality risk. Surgical haemostatic methods such as packing, hepatic artery ligation and hepatic suture may be helpful to contain the bleeding in cases of ruptured hemangioma[8].

Surgical resection and enucleation are considered the treatments of choice. The size and location of a lesion are decisive when the surgeon has to determine whether to perform either a formal segmental resection or an enucleation. Both procedures are typically performed by an open approach although laparoscopy can be both safe and well tolerated in some cases. Lesions of massive or diffuse nature, proximity to vascular structures and pre-existing comorbidities are limiting factors to surgical resection. In the absence of tumor promoting factors such as estrogen therapy, hemangiomas rarely recur after resection[1].

Recent studies have emphasized the use of transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization (TAE) in the effective treatment of larger symptomatic hemangiomas, for those at risk of bleeding and before exploratory laparotomy to treat patients with a hemorrhagic hemangioma. It can significantly improve outcome in such patients[16]. TAE as an alternative to surgery is still controversial because of the risk of ischemia, infection, abscess or intra abdominal bleeding[8].

The successful use of TAE before surgery of a ruptured hemangioma was first reported by Yamamoto et al in 1991[3]. A significant improvement in coagulative factors and a decrease in intraoperative blood loss was observed by Suzuki et al in patients with consumptive coagulopathy related to intravascular coagulation who were treated with preoperative TAE[3].

Radiofrequency ablation (open or laparoscopic) has been successfully used to improve abdominal pain in symptomatic hemangiomas. Other procedures such as radiotherapy should be reserved for poor candidates for surgery. It can produce regression of the hemangioma with minimal morbidity.

Orthotopic liver transplantation is occasionally offered to specific patients, including those with symptomatic and large or diffuse lesions.

CONCLUSION

Hemangiomas are common benign tumors of the liver, generally detected accidentally during a radiological screening performed for other reasons. In symptomatic cases, surgical treatment should be preferred[22]. Emergent hepatic resection has been the treatment of choice, but has high operative mortality. Preoperative transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) can significantly improve outcomes in such cases[3].

Spontaneous rupture in hemangiomas is not usual, but can be dramatic and very dangerous. Patients can die of massive hemorrhage in a short space of time and, in this situation, the patient is usually too weak to endure an operation[5] Ligation of hepatic artery or packing should be performed to control bleeding as soon as possible while hemodynamic stabilization is accomplished. If the hemorrhage is stopped and the patient’s condition is stable, a secondary operation to cure the hemangioma should be performed[4,8]. In a patient presenting with acute abdominal pain due to unknown abdominal disease, spontaneous rupture of a hepatic tumor such as hemangioma should be considered as a rare differential diagnosis[3].

According to the current literature, we conclude that the rate of spontaneous rupture of hepatic hemangiomas ranges from 1% to 4%, occurring mostly in giant hemangiomas (6-25 cm), with a mortality rate that can reach up to 75%. The operative mortality rate of this complication is around 36.4%[3,5,9,22,23]. So far, only 33 cases of spontaneous rupture of hepatic hemangiomas have been reported and published.

The right hepatic lobe, especially its posterior segment, is the most common site of appearance of these lesions. They are often subcapsular, well circumscribed and unencapsulated. Structurally, hemangiomas are composed of venous lakes, coated with endothelial tissue plus clots and calcification, separated by a connective tissue septa, where the blood circulates slowly. The growth of these tumors occurs by vascular ectasia, and never by hyperplasia or hypertrophy.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Tanios Bekaii Saab, MD, Medical Director, Gastrointestinal Oncology, Assistant Professor of Medicine and Pharmacology, Arthur James Cancer Hospital, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, United States; Andrea Mancuso, MD, Gastroenterology and Hepatology Department, Ospedale Niguarda Ca 'Granda, Piazza Ospedale Maggiore 3, Milan 20162, Italy

S- Editor Zhang HN L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Liu N

References

- 1.Wolf DC, Raghuraman UV Hepatic Hemangiomas. [Internet] New York (NY): Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatobiliary Diseases, Department of Medicine, New York Medical College; [Updated: Dec 8, 2009] Avaliable from: URL: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/177106-overview. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gourgiotis S, Moustafellos P, Zavos A, Dimopoulos N, Vericouki C, Hadjiyannakis EI. Surgical treatment of hepatic haemangiomas: a 15-year experience. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:792–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain V, Ramachandran V, Garg R, Pal S, Gamanagatti SR, Srivastava DN. Spontaneous rupture of a giant hepatic hemangioma - sequential management with transcatheter arterial embolization and resection. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:116–119. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.61240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tekin A, Kuçukkartallar ST, Esen H. Giant hepatic hemangioma treated with enucleation after selective portal ven embolization. Erciyes Med J. 2009;1:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen ZY, Qi QH, Dong ZL. Etiology and management of hemmorrhage in spontaneous liver rupture: a report of 70 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:1063–1066. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i6.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Güngör T, Aytan H, Tapisiz OL, Zergeroĝlu S. An unusual case of incidental rupture of liver hemangioma during labor. Chin Med J (Engl) 2004;117:311–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa SRP, Speranzini MB, Horta SH, Miotto MJ, Myake A, Henriques AC. Surgical treatment of painful hepatic hemangioma. Einstein. 2009;7:88–90. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vokaer B, Kothonidis K, Delatte P, De Cooman S, Pector JC, Liberale G. Should ruptured liver haemangioma be treated by surgery or by conservative means? A case report. Acta Chir Belg. 2008;108:761–764. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2008.11680334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aiura K, Ohshima R, Matsumoto K, Ishii S, Arisawa Y, Nakagawa M, Nakagawa M, Noga K. Spontaneous rupture of liver hemangioma: risk factors for rupture. J Hep Bil Pancr Surg. 1996;3:308–312. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto T, Kawarada Y, Yano T, Noguchi T, Mizumoto R. Spontaneous rupture of hemangioma of the liver: treatment with transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:1645–1649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corigliano N, Mercantini P, Amodio PM, Balducci G, Caterino S, Ramacciato G, Ziparo V. Hemoperitoneum from a spontaneous rupture of a giant hemangioma of the liver: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:459–463. doi: 10.1007/s10595-002-2514-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mungovan JA, Cronan JJ, Vacarro J. Hepatic cavernous hemangiomas: lack of enlargement over time. Radiology. 1994;191:111–113. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.1.8134554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moser C, Hany A, Spiegel R. [Familial giant hemangiomas of the liver. Study of a family and review of the literature] Praxis (Bern 1994) 1998;87:461–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatzoulis G, Kaltsas A, Daliakopoulos S, Sallam O, Maria K, Chatzoulis K, Pachiadakis I. Co-existence of a giant splenic hemangioma and multiple hepatic hemangiomas and the potential association with the use of oral contraceptives: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2008;2:147. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao X, Liu J, Sheng M. Synergistic effect of estrogen and VEGF on the proliferation of hemangioma vascular endothelial cells. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1107–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spitzer D, Krainz R, Graf AH, Menzel C, Staudach A. Pregnancy after ovarian stimulation and intrauterine insemination in a woman with cavernous macrohemangioma of the liver. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1997;42:809–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paulo Neto WT, Koifman ACB, Martins CAS. Rupture hepatic cavernous hemangioma: a cause report and literature review. Radiol Bras. 2009;42:271–273. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masui T, Katayama M, Nakagawara M, Shimizu S, Kojima K. Exophytic Giant Cavernous hemangioma of the liver with growing tendency. Radiat Med. 2005;23:121–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vossen JA, Buijs M, Liapi E, Eng J, Bluemke DA, Kamel IR. Receiver operating characteristic analysis of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in differentiating hepatic hemangioma from other hypervascular liver lesions. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2008;32:750–756. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31816a6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farges O, Daradkeh S, Bismuth H. Cavernous hemangiomas of the liver: are there any indications for resection? World J Surg. 1995;19:19–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00316974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krause T, Hauenstein K, Studier-Fischer B, Schuemichen C, Moser E. Improved evaluation of technetium-99m-red blood cell SPECT in hemangioma of the liver. J Nucl Med. 1993;34:375–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsai CC, Yen TC, Tzen KY. Pedunculated giant liver hemangioma mimicking a hypervascular gastric tumor on Tc-99m RBC SPECT. Clin Nucl Med. 1999;24:132–133. doi: 10.1097/00003072-199902000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Franco A, Monteforte MG, Maresca G, De Gaetano AM, Manfredi R, Marano P. [Integrated diagnosis of liver angioma: comparison of Doppler color ultrasonography, computerized tomography, and magnetic resonance] Radiol Med. 1997;93:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]