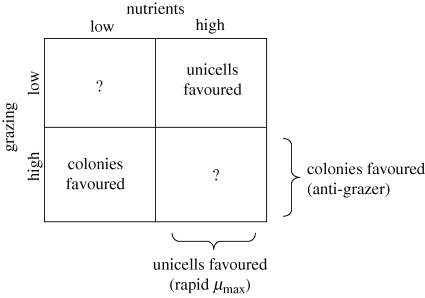

Figure 3.

The cost–benefit landscape of coloniality. For a phenotypically plastic trait to be considered adaptive there must be an underlying trade-off that favours one form in one environment but another form in another environment. Previous work on Desmodesmus spp. has shown a benefit to coloniality in offering some protection against herbivores, so coloniality is considered a benefit under high grazing conditions. The costs to coloniality have been more elusive, however, and the present study shows that unicells have higher growth rate under high nutrients. Hence, we can now consider unicells to be favoured over colonies under high nutrient conditions. These costs and benefits resolve into different morphs being favoured under different environmental states. Known costs and benefits do not make unequivocal predictions for two of the environmental states (marked with ‘?’).