Abstract

Objectives:

To determine the incidence of and risk factors for injury to the lower urinary tract during total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Methods:

All patients who underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease from January 1, 2002 to December 31, 2005, at an academic medical center are included. Subjects undergoing laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy, supracervical hysterectomy, or hysterectomy for malignancy were excluded. Intraoperative cystoscopy with intravenous indigo carmine was routinely performed. Relevant data were abstracted to determine the incidence of lower urinary tract injury, predictors of injury, and postoperative complications.

Results:

Total laparoscopic hysterectomy was performed in 126 consecutive subjects. Two (1.6%) cystotomies were noted and repaired before cystoscopy was performed. Two (1.6%) additional cystotomies were detected during cystos-copy. Absent ureteral spill of indigo carmine was detected in 2 subjects: 1 (0.8%) with previously unknown renal disease and 1 (0.8%) with ureteral obstruction that was relieved with subsequent suture removal. Only 40% (2/5) of injuries were recognized without the use of cystoscopy with indigo car-mine. The overall incidence of injury to the lower urinary tract was 4.0%. No subjects required postoperative intervention to the lower urinary tract within the 6-week perioperative period. Performing a ureterolysis was associated with an increased rate (odds ratio 8.7, 95%CI, 1.2-170, P=0.024) of lower urinary tract injury.

Conclusion:

Surgeons should consider performing cystoscopy with intravenous indigo carmine dye at the time of total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Keywords: Laparoscopic hysterectomy, Bladder injury, Ureter injury, Cystoscopy, Complication

INTRODUCTION

Hysterectomy is the most commonly performed major gynecologic surgical procedure worldwide and can be performed using an abdominal, vaginal, or laparoscopic approach.1 A recent systematic review and metaanalysis of 27 randomized controlled trials comparing these 3 methods of hysterectomy concluded that when vaginal hysterectomy is not possible the laparoscopic approach is preferable to the abdominal approach.2 Patients undergoing laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy return to normal activities quicker, have significantly shorter hospitalizations, fewer infections, and significantly lower mean blood loss, and drop in hemoglobin compared with patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy.2 However, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy appears to be associated with a higher risk of bladder and ureter injury than abdominal hysterectomy (odds ratio 2.6; 95% CI, 1.2 to 5.6).2 Detected injury rates are up to 5-fold higher when routine cystoscopy is performed than when routine cystoscopy is not performed, because cystoscopy recognizes some injuries that would have otherwise been missed.3 Such unrecognized injuries to the urinary tract during gynecologic surgery result in pain, suffering, loss of employment, adverse interpersonal relationships, and quality of life.4 Additionally, injury to the lower urinary tract during hysterectomy is associated with an increased risk of litigation when compared with other perioperative complications.4

Many variations of the laparoscopic hysterectomy have been described since its introduction by Reich et al in 1989.5 These modifications include relative portions of the procedure performed using the laparoscopic or vaginal route and may have a potential impact on complication rates. Technique differences between total laparoscopic hysterectomy and laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy are largely related to dissection of the bladder and ligation of the uterine vascular supply. During total laparoscopic hysterectomy, hemostasis of the uterine arteries is accomplished via the laparoscopic rather than the vaginal approach, the bladder is dissected completely off the lower uterine segment and upper vagina, and the vaginal cuff is closed by using a variety of laparoscopic suturing techniques. These techniques could potentially alter the risk of injury to the lower urinary tract.

Most of the available literature on injury to the lower urinary tract during laparoscopic hysterectomy is limited to laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy, and few studies look at the use of routine cystoscopy to diagnose these injuries.6,7 Therefore, the true risk of injury to the lower urinary tract from a total laparoscopic hysterectomy is unknown. The objectives of this study were to determine the incidence of and risk factors for injury to the lower urinary tract when routine cystoscopy is used while total laparoscopic hysterectomy is performed for benign disease and to determine the accuracy and efficacy of intraoperative cystoscopy to prevent postoperative lower urinary tract complications.

METHODS

Institutional review board approval was obtained. This was a retrospective cohort study design. All patients who underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy (AAGL Classification IVe)8 for benign disease at an academic, tertiary referral medical center from January 1, 2002 to December 31, 2005 are included. Subjects undergoing laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy, supracervical hysterectomy, or hysterectomy for malignancy were excluded. Intraoperative cystoscopy with intravenous indigo carmine dye was routinely performed at the end of the procedure to document bladder integrity and ureteral patency on all subjects. Relevant data were abstracted from health system-wide electronic records to determine the incidence and accuracy of intraoperative cystoscopy in the detection of lower urinary tract injury, potential predictors of injury, and the resulting postoperative complications. Dictated operative reports were reviewed to identify any intraoperative injury to the lower urinary tract. We defined injuries as the occurrence of cystotomy detected with or without cystoscopy, spillage of blue-stained urine into the peritoneal cavity after intravenous administration of indigo carmine, or absence of spill of blue-stained urine from one or both ureteral orifices visualized on cystoscopy. Discharge summaries, outpatient notes, and emergency room visits during the postoperative (≤6 weeks) period were reviewed to identify any injury or long-term sequelae to the lower urinary tract.

Total laparoscopic hysterectomy was performed with a 5-mm or 10-mm umbilical trocar, 2 bilateral lower quadrant 5/12-mm trocars, and a fourth 5-mm trocar located on the patient's left side, at the level of the umbilicus, in the midclavicular line. A total laparoscopic hysterectomy (AAGL Type IVe) was performed in which the entire uterus, adnexa, uterine and ovarian vasculature, and cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex were detached by using thermal coagulation with bipolar energy, and transection with entry into the vagina under laparoscopic guidance.8 The Rumi uterine manipulator with Koh cup (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, CT) was used in all cases. The monopolar hook was used to detach the uterus from the cervico-vaginal junction. The vaginal cuff was sutured with interrupted sutures of 0-polygalactin using an extracorporeal knot tying technique. If a McCall's culdoplasty was performed at the surgeon's discretion, a single 0-polypropylene or 0-polydiaxone suture was passed through the distal uterosacral ligament, into the midline posterior vaginal fibromuscular tissue, through the opposite distal uterosacral ligament and tied using an extracorporeal knot tying technique. Ureterolysis was performed only if visualization of the ureter was limited during the hysterectomy or if excising endometriosis was located on the pelvic sidewall overlying the ureter. During ureterolysis, the overlying peritoneum was completely removed away from the ureter, and adjacent disease, when present, was separated from the ureter and removed. Careful attention was paid to avoid devascularizing the ureter as much as possible.

Cystoscopic examination was performed in a standardized manner at the end of the hysterectomy, vaginal cuff closure, culdoplasty, and before removing the scope from the abdomen. An ampule of intravenous indigo carmine was administered, and the bladder was filled with at least non-300mL to 400mL of sterile watscope was inserted, and ureteral patency and bladder integrity were determinederee, 25 F cysto. Inspection of the peritoneal cavity was performed with the laparoscope as the bladder was filled to identify leakage of indigo carmine stained urine from the ureters bilaterally or from the bladder.l424

Univariate analyses were conducted with the Pearson χ2 statistic or Fisher's exact test for categorical data, the Student t test for continuous parametric data, and the Wilcoxan rank sum test for continuous nonparametric data. Logistic regression analyses were performed to adjust for possible confounding variables. Data are reported using odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) where appropriate. All statistical tests were 2-tailed, and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP 5.0.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

During the study period, 126 consecutive subjects underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy. All subjects underwent intraoperative cystoscopy at the end of the procedure. Demographic and intraoperative data are in Table 1. The majority of subjects were healthy, middle-aged, Caucasian women with a normal body mass index. Over half (53%) of subjects had a prior laparoscopy with 23% having had a prior cesarean delivery. The majority of subjects underwent hysterectomy secondary to dysmenorrhea or menorrhagia unresponsive to medical management. No conversions were necessary to laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy or open hysterectomy. The median operating time was just under 3 hours and median estimated blood loss was approximately 200 mL. Otherwise, no significant differences existed in demographic or operative characteristics between subjects with or without an injury to the lower urinary tract. Concomitant procedures are listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic and Intraoperative Variables of Patients Undergoing Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy (AAGL Classification IVe) With Routine Intraoperative Cystoscopy

| Demographics Intraoperative Factor | N |

|---|---|

| Age* | 42 ± 8 |

| Parity† | 1 (range, 0–5) |

| Non-Caucasian | 26 (21%) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2)† | 28.2 (range, 12.5–61.6) |

| Functional Status (METS)†‡ | 8 (range, 1–8) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index13 | 0 (range, 0–3) |

| Prior Surgery | |

| Laparoscopy | 59 (54%) |

| Laparotomy | 29 (27%) |

| Cesarean delivery | 28 (23%) |

| Adnexa | 23 (18%) |

| Incontinence | 2 (2%) |

| Other urologic | 5 (4%) |

| Ureteral obstruction | 1 (1%) |

| Colon | 7 (6%) |

| Indications for Hysterectomy | |

| Dysmenorrhea | 44 (35%) |

| Menorrhagia | 70 (56%) |

| Pelvic organ prolapse | 2 (2%) |

| Adnexal mass | 4 (3%) |

| Postmenopausal bleeding | 5 (4%) |

| Uterine Weight (G)† | 137 (range, 38–1340) |

| ASA score† | 1 (range, 1–3) |

| Estimated Blood Loss (mL)† | 200 (range, 10–1500) |

| Incision Time (min)† | 166 (range, 80–400) |

Table 2.

Concomitant Surgical Procedures Performed With Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy (AAGL Classification IVe) With Routine Intraoperative Cystoscopy

| Procedure | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Oophorectomy, unilateral | 36 | 28.5 |

| Oophorectomy, bilateral | 10 | 7.9 |

| Ovarian cystectomy | 4 | 3.1 |

| Prophylactic McCall's culdoplasty | 58 | 46.0 |

| Ureterolysis | 42 | 33.3 |

| Lysis of adhesions | 51 | 40.5 |

| Burch cystourethropexy | 3 | 2.4 |

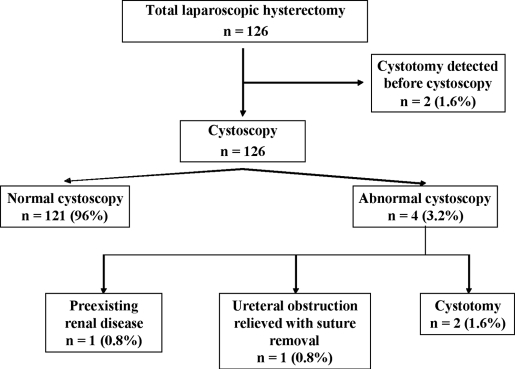

The results of intraoperative cystoscopy with intravenous indigo carmine to assess bladder integrity and ureteral patency during total laparoscopic hysterectomy are illustrated in Figure 1. Two (1.6%) cystotomies were noted during the operative procedure and were repaired before cystoscopy was performed. Two additional cystotomies (1.6%) were detected during cystoscopy. Absent spill of blue-stained urine was detected in 2 subjects. A 5 F ureteral stent was successfully passed during the initial procedure in 1 (0.8%) subject who was later found to have previously unknown renal disease. One additional (0.8%) subject had a ureteral obstruction that was relieved with subsequent suture removal during the initial operative procedure. The overall incidence of injury to the lower urinary tract was 4.0% (95% CI; range, 1.7 to 9.0). Only 40% of injuries (2 cystotomies out of 5 injuries) were detected without the use of routine cystoscopy with intravenous indigo carmine. Additionally, the single subject with preexisting renal disease would not have been diagnosed without cystoscopy. No subjects required postoperative intervention to the lower urinary tract within the 6-week perioperative period. Performing a ureterolysis was associated with an increased rate (unadjusted OR 8.7, 95% CI, range 1.2 to 170, P=0.024) of lower urinary tract injury.

Figure 1.

Intraoperative cystoscopy with intravenous indigo carmine dye to assess bladder integrity and ureteral patency during total laparoscopic hysterectomy (AAGL Classification IVe) for benign gynecologic disease.

DISCUSSION

A higher risk of injury to the ureter or bladder may exist with total laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy involves ligation of the upper uterine ligaments including the round, uteroovarian, and infundibulopelvic. The remaining portion of the procedure is performed vaginally and, similar to vaginal hysterectomy alone, has a low incidence of injury to the lower urinary tract.1,11,12 In contrast, total laparoscopic hysterectomy involves dissecting the uterus free from all attachments in the peritoneal cavity and removing it via morcellation or through an open vaginal cuff. The bladder is dissected completely off the vaginal tissue, potentially increasing the likelihood of bladder injury. Additionally, there is a tendency to drift laterally with the instruments and improperly utilizing traction and countertraction of the uterus when maintaining hemostasis at the level of the uterine artery. Thermal spread from coagulation devices or suture ligating excessive tissue during uterine artery occlusion or vaginal cuff closure may result in excessive tension on the peritoneum, resulting in ureteral kinking and subsequent obstruction.

This study reports on a series of patients and describes an intraoperative injury rate to the lower urinary tract during total laparoscopic hysterectomy of approximately 4%. Councell et al6 reported on 171 women who underwent laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy with routine cystoscopy. There were 5 bladder injuries and 1 ureteral injury for a total injury rate of 3%. The authors used a combination of instruments for hemostasis including electrocoagulation, endoscope stapling devices, and extracorporeal sutures. Different methods of hemostasis have since been shown to be associated with a higher risk of complications.11 Ribeiro et al7 reported on 118 of 278 patients who underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy. The overall ureteral injury rate was 3.4%, and the authors did not report a bladder injury rate. Thirteen percent of patients reported on by Ribeiro et al7 underwent a surgical technique that could alter the risk of urinary tract injury including laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (6%), laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (1%), laparoscopic hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy (4%), and radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy (2%). Moreover, routine cystoscopy was not performed on all 278 patients, raising the possibility for selection bias.

This study also investigated the value of intraoperative cystoscopy as a secondary prevention strategy of detecting and repairing intraoperative bladder injury and ureteral obstruction during total laparoscopic hysterectomy. The rates of injury to the lower urinary tract during laparoscopic hysterectomy appear to be higher when routine cystoscopy is performed, because cystoscopy detects injuries that would have otherwise been missed.3 Only 40% of injuries were detected without the use of routine cystoscopy with intravenous indigo carmine. These data are consistent with those of Gilmour et al3 who reported that the rate of injury to the bladder during gynecologic surgery increases from 6.0 per 1,000 surgeries without cystoscopy to 29.2 per 1,000 surgeries with routine cystos-copy. The rate of injury to the ureter increases from 7.3 per 1,000 surgeries without routine cystoscopy to 14.5 per 1,000 surgeries with routine cystoscopy.3 When surgeons do not use routine cystoscopy during gynecologic surgery, they seem to recognize and manage many bladder injuries, but not many ureteric injuries.3 This is consistent with our data with only 2 bladder injuries that were detected without cystoscopy, while the remaining bladder and ureteral injuries were identified only after cystoscopy with intravenous indigo carmine dye. Additionally, these data confirm previous reports that ureteral injuries can be detected when using routine cystoscopy, and intervention minimizes long-term sequelae.

Routine cystoscopy during total laparoscopic hysterectomy may also be cost saving. Visco et al13 evaluated the cost effectiveness of routine cystoscopy during abdominal, vaginal, and laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. Using a hospital-based perspective, it was cost saving to perform routine cystoscopy if the rate of ureteral injury exceeded 2% for laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. This analysis was based only on the rate of ureteral injury and did not include bladder injury. Cost effectiveness was largely influenced by the incidence of ureteral injury and the cost of readmission to the hospital. These data combined with the minimal risk cystoscopy exposes to the patient mean procedures with elevated rates of injury to the lower urinary tract, such as vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence12 and laparoscopic hysterectomy, would actually save money if cystoscopy were performed on a routine basis.6

The association between ureterolysis and injury to the lower urinary tract in our data may have several explanations. Ureterolysis has been shown to interfere with the healing process of an injured ureter by increasing fibrosis and adventitial scarring.14 Performing ureterolysis may be an indicator of a host of confounding factors, such as uterine weight or length of operating time, that result in a higher degree of surgical difficulty. Since ureterolysis was performed in cases where visualization of the ureter was difficult, we do not know how often ureterolysis allowed for improved visualization of the ureter and prevented a urinary tract injury. Based on these data, we recommend at least identifying the ureters during total laparoscopic hysterectomy and when possible keeping them within the field of vision during the procedure. Although this may necessitate performing ureterolysis, the surgeon should attempt to minimize routine dissection of the ureter as this procedure alone may increase the risk of injury.

This study has several strengths and weaknesses. We report injury rates by using a single standard method of laparoscopic hysterectomy (Type IVe). All subjects had intraoperative cystoscopy, minimizing potential selection bias. However, it is possible that injuries could be missed, because we did not routinely perform imaging of the ureters or kidneys postoperatively.

We also reviewed records from health system-wide computerized medical records, thereby reducing, although not eliminating, the risk of reporting bias to our office. Patients may have presented outside of our health system with injury during the postoperative period. Additionally, surgical complication rates at a tertiary care center may not be generalizable to community surgeons. A surgeon's expertise could potentially elevate (eg, operating on difficult cases that are referred from the community) or reduce (technically superior due to a higher volume of cases) the risk of injury to the lower urinary tract. Finally, the rate of injury is low, limiting our ability to conclude significant differences between methods of laparoscopic hysterectomy. We can only speculate that large differences are unlikely.

CONCLUSION

Intraoperative cystoscopy allows for recognition of unsuspected lower urinary tract injury and prevention of long-term complications. At our institution, routine cystoscopy is performed for all benign surgical procedures with an elevated risk of injury to the lower urinary tract. This includes surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence and all laparoscopic hysterectomies. Based on our data, cystoscopy should be considered at the time of total laparoscopic hysterectomy to reduce the risk of long-term sequelae resulting from injury to the lower urinary tract.

References:

- 1. Makinen J, Johansson J, Tomas C, et al. Morbidity of 10,110 hysterectomies by type of approach. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1473–1478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johnson N, Barlow D, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr L, Garry R. Methods of hysterectomy: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2005;330:1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gilmour DT, Das S, Flowerdew G. Rates of urinary tract injury from gynecologic surgery and the role of intraoperative cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1366–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gilmour DT, Baskett TF. Disability and litigation from urinary tract injuries at benign gynecologic surgery in Canada. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:109–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reich H. Laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Gynecol Surg. 1989;5:213–217 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Councell RB, Thorp JM, Jr., Sandridge DA, Hill ST. Assessments of laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1994;2:49–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ribeiro S, Reich H, Rosenberg J, Guglielminetti E, Vidali A. The value of intra-operative cystoscopy at the time of laparoscopic hysterectomy. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1727–1729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Olive DL, Parker WH, Cooper JM, Levine RL. The AAGL classification system for laparoscopic hysterectomy. Classification committee of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7:9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eagle KA, Brundage BH, Chaitman BR, et al. Guidelines for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery. Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Committee on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 1996;93:1278–1317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garry R, Fountain J, Mason S, et al. The eVALuate study: two parallel randomised trials, one comparing laparoscopic with abdominal hysterectomy, the other comparing laparoscopic with vaginal hysterectomy. BMJ. 2004;328:294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gustilo-Ashby AM, Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Yoo EH, Paraiso MF, Walters MD. The incidence of ureteral obstruction and the value of intraoperative cystoscopy during vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1478–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Visco AG, Taber KH, Weidner AC, Barber MD, Myers ER. Cost-effectiveness of universal cystoscopy to identify ureteral injury at hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:685–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Margossian H, Falcone T, Walters MD, Biscotti C. Laparoscopic repair of ureteral injuries. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:373–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]