Abstract

Objective

Accurate time estimation abilities are thought to play an important role in efficient performance of many daily activities. This study investigated the role of episodic memory in the recovery of time estimation abilities following moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Method

Using a prospective verbal time estimation paradigm, TBI participants were tested in the early phase of recovery from TBI and then again approximately one year later. Verbal time estimations were made for filled intervals both within (i.e., 10 s, 25 s) and beyond (i.e., 45 s 60 s) the time frame of working memory.

Results

At baseline, when compared to controls, the TBI group significantly underestimated time durations at the 25 s, 45 s and 60 s intervals, indicating that the TBI group perceived less time as having passed than actually had passed. At follow-up, despite the presence of continued episodic memory impairment and little recovery in episodic memory performance, the TBI group exhibited estimates of time passage that were similar to controls.

Conclusion

The pattern of data was interpreted at suggesting that episodic memory performance did not play a noteworthy role in the recovery of temporal perception in TBI participants.

Keywords: time estimation, temporal perception, temporal cognition, traumatic brain injury, closed head injury

The investigation of time estimation abilities is an important topic given that it has been argued to assist with the ability to organize activities (Kielhofner, 1977), contribute to the experience of emotions (Zakay & Block, 1997) and be important for activities of daily living, such as cooking (Block & Zakay, 1997). For example, when preparing a meal, an individual must accurately estimate time intervals to efficiently complete the steps of the task. Past studies have found that neurologically normal adults are relatively accurate judging the passage of time (e.g., Kinsbourne & Hicks, 1990; Rao, Mayer, & Harrington, 2001; Schmitter-Edgecombe & Rueda, 2008; Rueda & Schmitter-Edgecombe, 2009). Despite the implications of correct time estimations for everyday activities, few studies have explored time estimation abilities following traumatic brain injury (TBI; Meyers & Levin, 1992; Perbal, Couillet, Azouvi, & Pouthas, 2003; Schmitter-Edgecombe & Rueda, 2008). Furthermore, no study that we are aware of has longitudinally followed individuals recovering from TBI and assessed time perception. In the current study, we used a verbal prospective time estimation paradigm to investigate time perception during the first year of recovery in individuals with moderate to severe TBI.

Multiple theories have been proposed to explain how individuals estimate time, including state-dependent networks (Buonomano & Karmarkar, 2002; Mauk & Buonomano, 2004) and variations of internal clock models (for review, please see Eagleman, Tse, Buonomano, Janssen, Nobre, & Holcombe, 2005; Matell & Meck, 2000). As an example of a biological internal clock model, in the Scalar Timing Model (Gibbon, 1977; Gibbon, Church, & Meck, 1984), the clock generates neuronal pulses, which are proposed to be collected by a counter within working memory. The accumulation of pulses is then compared with learned time labels for durations stored in reference memory (Nichelli, Venneri, Molinari, Tavani, & Grafman, 1993; Perbal et al., 2003). The comparison between these accumulated pulses and learned temporal representation then determines a participant’s time estimate (e.g., overestimate, underestimate).

The attentional-gate model (Zakay & Block, 1996, 1997; Zakay, Block & Tsal, 1999) expands on Scalar Timing Theory by identifying that perception of time is influenced by both biological factors, such as body temperature (e.g., Wearden & Penton-Voak, 1995) and physiological arousal (e.g., Cahoon, 1969; Marum, MacIntyre, & Armstrong, 1972), and psychological factors, such as attention (e.g., Burnside, 1971; Chaston & Kingstone, 2004) and memory (Fraise, 1957/1963; Ornstein, 1969). Research into biological and psychological conditions that can alter an individual’s perceived duration of time suggests that a person’s accuracy in estimating an interval of time relies on multiple factors. For example, studies suggest that the rate of subjective time increases when body temperature is increased above normal and decreases when body temperature is lowered below normal (for a review, see Wearden & Penton-Voak, 1995). As an example of the effects of psychological factors, when attention is occupied by a non-temporal cognitively demanding task, a systematic shortening of time duration has been found to occur (e.g., Chaston & Kingstone, 2004; Hicks, Miller & Kinsbourne, 1976; Polyukhov, 1989).

To investigate an individual’s perception of duration timing, both retrospective and prospective time estimation procedures have been used (Block & Zakay, 1997). In the retrospective paradigm, participants are not cued in advance that they will be asked to estimate time durations. The prospective time estimation paradigm, however, involves participants knowing before the experimental task that they will be asked to estimate the length of time that has passed. This methodology has been argued as the preferable method to investigate time estimation. Studies using the retrospective time estimation paradigm have suggested that individuals can become attentive to temporal cues and unwittingly shift cognitive resources to processing temporal information (Block, 1990; Block & Zakay, 1997), especially when tasks are boring (Doob, 1971). In addition, and perhaps more importantly, prospective estimates have been found to be more accurate than retrospective judgments of time (Block & Zakay, 1997).

To obtain prospective duration judgments, a “classic trio” (Wearden, 2003) of methods have been primarily utilized: a production method in which participants are asked to indicate when a stated time has elapsed (Licht, Morganti, Nehrke, & Heiman, 1985); a reproduction method where participants are exposed to given time durations and subsequently indicate when the same time duration has passed (Shaw & Aggleton, 1994); and a verbal estimation method in which participants are exposed to duration intervals and subsequently asked to verbally estimate duration length (Licht, et al., 1985). Although past research has found these methods to produce statistically similar results (Block & Zakay, 1997), the verbal estimation method is thought to be the preferable method for studying the sense of time passing (Kinsbourne, 2000). For example, it has been argued that the reproduction method does not rely on conventional duration units (e.g., seconds) as no comparison of subjective time to objective clock time is thought necessary (Cahoon, 1969; Block, Zakay, & Hancock, 1998). Furthermore, in a prior study conducted with individuals with TBI, Meyers and Levin (1992) argued that the reproduction method was an unreliable procedure for assessing time estimation in the TBI population. In addition, both the production and reproduction methods are more susceptible than the verbal estimation method to confounding variables such as impatience or difficulties in delaying response (Block et al., 1998). The verbal estimation method relies on the “scaling” of subjective time (Wearden, 2003). That is, this method relies on how an individual’s subjective duration of time relates to actual units of time. For example, if an estimate is shorter than the actual time units, participants are thought to be experiencing the passage of time more slowly.

To date, few studies have investigated time estimation abilities in a TBI population (Meyer & Levin, 1992; Perbal et al., 2003; Schmitter-Edgecombe & Rueda, 2008). Perbal and colleagues (2003) investigated time perception in 15 individuals with severe TBI tested 4 to 41 months post-injury. These authors found no group difference between TBI and control participants in experienced temporal durations. Specifically, using both production and reproduction tasks for intervals of 5 s, 14 s, and 38 s, TBI participants performed similar to controls in accuracy (i.e., ratio scores) but demonstrated greater timing variability (i.e., coefficient of variance scores). These researchers argued that individuals with TBI did not demonstrate impairment in time estimation, per se, but rather that time estimation response consistency was related to deficits in cognitive functions such as attention and working memory. In an early study with TBI participants, Meyers and Levin (1992) investigated time estimation 5 to 590 days post-injury in 34 individuals with TBI ranging from mild to severe. Using a reproduction method for 5 s, 10 s and 15 s time intervals these authors found that individuals with TBI did not differ from controls in their time estimations. However, Meyers and Levin further argued that those individuals with TBI who had difficulties transferring information from short-term memory into long-term memory also had greater difficulties estimating the longer time duration (i.e., 15 s).

In a recent study from our laboratory (Schmitter-Edgecombe & Rueda, 2008), we examined time estimation accuracy for two intervals within the time span of working memory (i.e., less than 30 seconds; Kinsbourne & Hicks, 1990; Mimura, Kinsbourne, & O’Conner, 2000) and two intervals requiring the need for episodic memory (Mimura et al., 2000). Participants in the early stages of recovery following TBI provided prospective verbal time estimates for short (i.e., 10 s, 25 s) and long (i.e., 45 s, 60 s) intervals. The findings revealed that TBI participants produced normal or near normal estimates for temporal durations less than 30 s, but were less accurate than controls judging longer intervals. More specifically, the TBI participants significantly underestimated the longer time durations. Schmitter-Edgecombe and Rueda suggested that episodic memory dysfunction may account for the poorer accuracy of the TBI participants at durations that exceeded the time frame of working memory, a result that has also been found in other neurological populations with long-term memory deficits (i.e., amnestic disorders; Kinsbourne, 2000; Mimura et al., 2000; Perbal, Pouthas, & Vander Linden, 2000; Richards, 1973; Williams, 1988).

In the present study, we retested the TBI and control participants from the Schmitter-Edgecombe and Rueda study (2008) approximately one year following initial testing. We were interested in whether the time estimation accuracy of the TBI participants for the 45 s and 60 s intervals would improve to normal levels following a year of recovery. Given that Schmitter-Edgecombe and Rueda hypothesized that episodic memory dysfunction may have accounted for the poorer time estimates of the TBI group at the longer time intervals (i.e., > 30 s), we were particularly interested in whether improvements in episodic memory ability during the first year of recovery would be associated with concomitant improvements in time perception abilities for the longer durations. Multiple past studies have found that individuals with TBI in the early stages of recovery perform more poorly on tests of episodic memory than controls (e.g., Anderson & Schmitter-Edgecombe, 2008; Sunderland, Harris, & Baddeley, 1983; Vanderploeg et al., 2001), but demonstrate a good recovery curve of memory abilities within the first year post-injury (Christensen et al., 2008).

Methods

Participants

Fifteen individuals (5 females, 10 males) who had suffered a moderate to severe TBI and 15 neurologically normal controls (6 females, 9 males) participated in this study. The TBI participants represent a subset of the 27 TBI individuals who participated in the time estimation study by Schmitter-Edgecombe and Rueda (2008) and who agreed to retesting approximately one year later. The TBI participants were originally identified by consecutive admissions to a regional traumatic brain injury inpatient rehabilitation program in the Pacific Northwest and tested within 5 weeks of emergence from post-traumatic amnesia (see Schmitter-Edgecombe & Rueda for additional details). The 15 TBI participants who agreed to be retested after a one year recovery did not differ from the 12 TBI participants who were not retested in age (returners: M = 33. 87; non-returners: M = 31.75, t = .39), education (returners: M = 12.53; non-returners: M = 12.75, t = −.23), sex (returners: 5F, 10M; nonreturners: 4F, 8M ), or performance on the Shipley Institute of Living Scale vocabulary test (returners: M = 26.93; non-returners: M = 25.90, t = .29). TBI participants received feedback regarding their cognitive functioning in return for their time. Control participants were recruited from the community through the use of advertisements and received monetary compensation.

Eight of the TBI participants suffered a severe TBI; defined by a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS; Teasdale & Jennett, 1974) score of 8 or less, documented at the scene of the accident or in the emergency room. The remaining seven TBI participants suffered a moderate TBI classified by a GCS between 9 and 12 (n = 4) or by a GCS of higher than 12 accompanied by positive neuroimaging findings and/or neurosurgery (n = 3; Dennis et al., 2001; Fletcher et al., 1990; Taylor et al., 2002; Williams, Levin, & Eisenberg, 1990). The majority of the TBI participants experienced a coma duration longer than two hours as reported in medical records or by careful clinical questioning of the participant and/or knowledgeable informant, such as a family member (M = 53.07; SD = 107.20; range = 0 – 336 hours). All participants exhibited an extended period of post-traumatic amnesia (PTA; M = 23.27; SD = 15.85; range = 1 – 52 days). Emergence from PTA was determined either by repeated administration of the Galveston Orientation and Amnesia Test (GOAT; n = 9; Levin, O’Donnell, & Grossman, 1979) or, in those cases where the TBI participant had emerged from PTA prior to arriving at the rehabilitation institute, by careful clinical questioning of the TBI participant to recall their memories after the injury in chronological order until the examiner was satisfied that normal continuous memory was being described (n = 6; King et al, 1997; McMillan, Jongen, & Greenwood, 1996). For the baseline session, the majority of TBI participants were assessed within 3 weeks of emergence from PTA (n = 11) (M = 14.53 days; SD = 14.18, range = 1 – 34 days) with time since injury ranging from 13 – 68 days (M = 37.80, SD = 18.30). Participants were then retested approximately one-year after their baseline session, with time since injury ranging from 388 – 480 days (M = 432.13, SD = 32.72).

Twelve TBI participants suffered their head injuries as a result of a motor vehicle or motorcycle accident, two incurred injury from a fall of greater than 10 feet and one TBI participant experienced a blow to the head. To minimize possible developmental effects on performance, TBI participants under the age of 15 or over the age of 55 were excluded. Participants were also excluded from this study if they had a pre-existing neurological, psychiatric, or developmental disorder(s) other than a TBI, a history of treatment for substance abuse, or a history of multiple head injuries. All participants demonstrated adequate visual acuity at a distance of 16 inches (i.e., 20/60 vision using both eyes).

To increase the likelihood that the 15 TBI participants’ premorbid abilities were roughly equivalent to those of the controls, the age (M = 33.87; SD = 15.91) and educational level (M = 12.53; SD = 2.72) of the TBI participants was closely matched to the age (M = 32.93; SD = 14.95; t = .16) and educational level (M = 14.07; SD = 3.41; t = −1.36) of the control participants. In addition, an estimate of premorbid Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R) Verbal Intelligence Quotient (VIQ) derived from the Barona Index equation (Barona, Reynolds, & Chastain, 1984), which takes into account six demographic variables (i.e., age, sex, race, education, occupation, and region), revealed that the TBI (M = 102.03; SD = 9.04) and control (M = 104.91; SD = 10.43) groups did not differ significantly in premorbid abilities, t = −.81. The control participants were tested at baseline and then again one year later (M = 373; SD = 20.36; range = 346 – 423).

Apparatus and Stimuli

The apparatus and stimuli used for administration of the time estimation task were identical at baseline and follow-up. An IBM-compatible computer with SuperLab Pro Beta Version Experimental Lab Software (1999) was used to display the stimuli. All characters were presented in 64 pt Times New Roman, black bold font on a white background.

Procedure

Participants completed a prospective verbal time estimation task wherein they were instructed in advance that their task was to estimate (in seconds) how long each trial had lasted. The procedure used for administration of the time estimation task was identical at baseline and follow-up. More specifically, during each trial, in the center of a computer screen, the numbers 1 through 9 appeared in a random sequence at random intervals (i.e., between one to three seconds) and participants were instructed to read the digits aloud. These filled durations were utilized to minimize counting or other monitoring strategies which could allow a participant to estimate an interval without using memory abilities (Williams, 1988).

Participants were instructed to estimate in seconds how long each trial lasted. Participants were provided three practice trials; all participants indicated that they understood the task prior to administration of the experimental trials. The experimental task consisted of 16 trials with time intervals of 10 s, 25 s, 45 s, and 60 s, in which each interval was randomly presented four times. The same interval was not presented more than two times in a row. At the end of each timed interval, the participant was queued to estimate how long the trial lasted by a question—“How long did that trial last?”—that appeared in the center of the computer screen. The participant’s verbal time estimate was recorded by the examiner without providing feedback regarding the accuracy of their estimation or number reading. The time estimation task took approximately 20 minutes to administer.

Results

Time Estimation Task Scoring

Three scores were derived from the verbal time estimation task: (a) raw scores, (b) ratio scores, and (c) coefficient of variance. The ratio score reflects the direction and magnitude of the error and provided an index of accuracy regardless of the size of the standard interval. The ratio score was calculated by dividing the participants’ estimate by the actual time (Licht et al., 1985). For this variable a score of 1.00 would equal perfect estimations, while scores above 1.00 reflect overestimations, and scores below 1.00 reflect underestimations. The coefficient of variance index is a measure of timing variability and allowed us to evaluate how consistent participants were in their verbal estimates of the same target interval. The coefficient of variance index was calculated for each participant at each interval by dividing the standard deviation by the mean judgment, as indicated by Brown (1997).

Statistical Analysis

Mixed-model analyses of variance (ANOVA) were run separately for each of the three variables with group (TBI vs. controls) as the between subjects factor and interval (10 s, 25 s, 45 s, and 60 s) and testing session (baseline and follow-up) as the within-subjects factors. For analyses in which the condition of sphericity was not met, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used to make the F test more conservative (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). In all cases, the Greenhouse-Geisser adjustment factor was still significant suggesting no increased risk of type I error. Therefore, we report the standard univariate analysis data (Myers & Well, 2003). All time estimation trials were included in the analyses as participants made very few errors in reading the numbers used to fill the durations intervals (i.e., errors in number reading were made on less than .05 % of the time estimation trials).

Raw Scores

As expected, the group by interval by testing time mixed model ANOVA on the raw scores revealed that the groups provided increasingly larger time duration estimates as the length of time to be estimated increased (10 s: M = 7.28; 25 s: M = 17.54; 45 s: M = 32.61; 60 s: M = 43.52), F(3, 84) = 303.95, MSE = 115.56, p < .001, η2 = .92. The main effects for group, F(1, 28) = 6.32, MSE = 307.12, p < .05, η2 = .18, and testing session, F(1, 28) = 4.92, MSE = 304.71, p < .05, η2 = .15, and the significant interactions between group and interval, F(3, 84) = 6.38, p = .01, η2 = .19, and interval and testing session, F(3, 84) = 3.78, p < .05, were modified by the three-way interaction, F(3, 84) = 3.78, MSE = 73.76, p < .01, η2 = .12. There was no significant group by testing session interaction (F = 2.82).

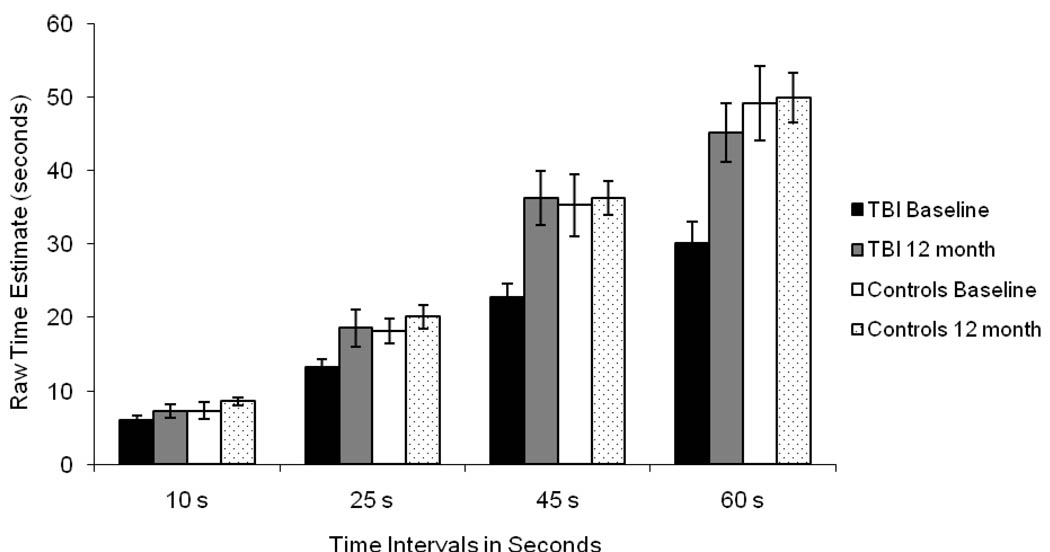

To breakdown the three-way interaction, separate group by interval ANOVAs were conducted on the baseline and the follow-up data. In addition to the expected main effect of interval, the ANOVA on the baseline data revealed a significant main effect of group, F(1, 28) = 8.63, MSE = 311.87, p < .01, η2 = .24, and a significant group by interval interaction, F(3, 84) = 9.83, MSE = 48.38, p < .001, η2 = .26. As seen in Figure 1, at baseline the TBI participants significantly underestimated the 25s (t = −2.50, p = .02), 45 s (t = −2.78, p = .01) and 60 s (t = −3.24, p = .003) intervals when compared to controls. There were no group differences at baseline in mean estimates for the 10s interval (t = 2.19). In contrast, the ANOVA on the follow-up data revealed only the expected significant main effect of interval. The main effect of group (F = .36) and the group by interval interaction (F = .72) were not significant as the TBI and control groups did not differ in their mean time estimate for any of the time intervals (ts < 1.2) at follow-up. This suggests an improvement in time estimation abilities during the first year of recovery by TBI participants to a level similar to controls.

Figure 1.

Mean Raw Scores for Time Intervals at Baseline and 12-month Follow-up for the Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and Control Groups.

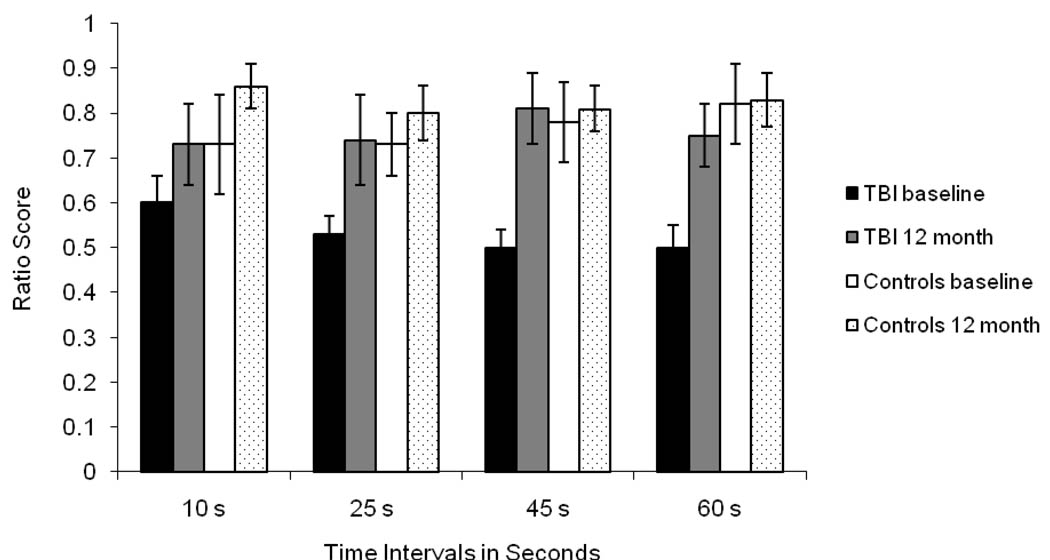

Ratio Score

The ANOVA analysis on the ratio score revealed significant main effects of group, F(1, 28) = 5.29, MSE = .25, p < .05, η2 = .16, and testing session, F(1, 28) = 4.59, MSE = .26, p < .05, η2 = .14, that were modified by a significant three-way interaction between group, interval, and testing session, F(3, 84) = 4.13, p < .05, η2 = .13. Neither the main effect of interval, F = .34, nor any of the two-way interactions, F < 1.56, were significant. As seen in Figure 2, the ratio of estimated time to actual time was similar across intervals at baseline and at follow-up for both the TBI and control groups.

Figure 2.

Mean Ratio Scores for Time Intervals at Baseline and 12-month Follow-up for the Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and Control Groups.

To break down the three-way interaction, separate interval by testing session ANOVAs were conducted for the TBI and control groups. The ANOVA for the TBI group revealed a significant main effect of testing session, F(1, 14) = 5.65, MSE = .26, p < .05, η2 = .29, and a significant interval by testing session interaction, F(3, 42) = 2.74, MSE = 311.87, p = .05, η2 = .17. As seen in Figure 2, in comparison to follow-up, the TBI participants demonstrated a greater magnitude of underestimation at baseline for the 45 s (t = −3.03, p < .01) and the 60 s (t = −2.90, p = .01) intervals, while the 25 s interval approached significance (t = −1.83, p = .08). There was no difference in the magnitude of underestimation between baseline and follow-up for the 10 s interval (t = −1.22). In contrast, for the control group, the magnitude of underestimation remained stable across the testing session for each time interval, ts < 1.1. In addition, while the TBI group demonstrated a more pronounced degree of underestimation of clock time than controls at baseline for the 25 s, 45 s and 60 s intervals, ts > 2.47, ps < .05, there were no group differences in ratio scores at follow-up, ts < 1.29.

Coefficient of Variance Score

The ANOVA analysis of the coefficient of variance score revealed that response consistency did not differ between the TBI (M = .24) and control (M = .21) groups, F = 2.1, or between the baseline (M = .23) and follow-up (M = .22) testing sessions, F = .62. There was a significant main effect of interval, F(3, 84) = 3.46, MSE = .02, p < .05, η2 = .11. Pairwise comparisons using the Sidak adjustment for multiple comparisons revealed that the groups exhibited less variability in estimates for the 60 s interval (M = .18) compared to the 25 s interval (M = .26, p < .05). Response consistency at the 45 s interval (M = .23) and the 10 s interval (M = .24) fell between the 60 s and 25 s intervals and did not differ statistically from any other time interval. Importantly, there were no significant two-way interactions, Fs < 1, and the three-way interaction involving group also did not reach significance, F < 1.2. These findings indicate that the response consistency of the TBI and control groups remained constant across the baseline and follow-up testing sessions and changed similarly across time intervals.

Neuropsychological Data

Means and standard deviations of the TBI and control groups on several neuropsychological tests are presented in Table 1 for both baseline and follow-up testing. Separate group by testing session ANOVAs conducted on the neuropsychological measures revealed that, compared to controls, TBI participants demonstrated disproportionately improved performances at the one year follow-up on the Trail Making Test (Reitan, 1958) Part A, F(1, 27) = 4.33, p < .05, η2 = .14, and Part B, F(1, 27) = 7.63, p < .01, η2 = .22. The group by testing session interaction approached significance, suggesting a greater improvement in scores by the TBI group on the following measures: Oral subtest from the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT; Smith, 1991), F(1, 27) = 3.03, p = .09, η2 = .10 ; Letter-Number Sequencing subtest from the WAIS-III (Wechsler, 1997), F(1, 27) = 2.84, p =.10, η2 = .10; and the Controlled Oral Word Association test (COWA; Benton, Hamsher, & Sivan, 1994), F(1, 27) = 1.81, p = .19, η2 = .06.

Table 1.

Demographic Data and Mean Summary Data at Baseline and Follow-up for the Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and Control Groups.

| Baseline | 12-month Follow-up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBI | Controls | TBI | Controls | |||||

| Test Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Attention/Speeded Processing | ||||||||

| SDMT Total Oral Correct | 42.00 | 12.08 | 63.47*** | 8.73 | 56.93 | 19.96 | 71.13* | 12.77 |

| SDMT Total Written Correct | 35.47 | 12.21 | 53.87*** | 6.81 | 47.07 | 12.86 | 63.53** | 10.87 |

| Trails A (time) | 45.07 | 20.26 | 23.60** | 6.56 | 33.21 | 15.55 | 19.93** | 4.08 |

| Episodic Memory | ||||||||

| RAVLT Trials 1–5 Total Recall | 45.71 | 11.23 | 59.00*** | 4.00 | 48.86 | 11.71 | 60.33** | 7.93 |

| RAVLT Long-Delay Free Recall | 7.71 | 3.97 | 12.53*** | 2.29 | 9.71 | 4.07 | 13.86** | 1.29 |

| 7/24 Trials 1–5 Total Recall | 31.23 | 4.97 | 32.80 | 2.96 | 31.07 | 4.97 | 34.27* | 1.67 |

| 7/24 Long-Delay Free Recall | 5.77 | 1.83 | 5.60 | 1.99 | 6.27 | 1.44 | 6.27 | 1.44 |

| Executive Functioning | ||||||||

| 5-Point Test | 24.27 | 12.01 | 40.20*** | 6.57 | 31.13 | 14.74 | 43.60** | 7.26 |

| Trails B (time) | 112.07 | 47.78 | 53.47*** | 10.37 | 73.00 | 36.64 | 38.67** | 11.57 |

| WAIS-III L-N Sequencing | 9.27 | 2.87 | 11.93** | 2.02 | 10.79 | 3.89 | 11.79 | 2.39 |

| Controlled Oral Word Test | 24.93 | 9.06 | 44.07*** | 12.84 | 34.57 | 8.98 | 58.60** | 11.48 |

Notes. Mean scores are raw scores. TBI = traumatic brain injury; Con = control; SDMT = Symbol Digit Modalities Test; RAVLT = Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; WAIS-III = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition; L-N = Letter-Number. Controlled Oral Word Test letters = PRW.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

In contrast to the notable improvements on the above measures assessing speeded processing, attention, and executive functioning skills, the TBI participants exhibited little improvement between baseline and follow-up on the memory measures. More specifically, the TBI group’s performance on the verbal learning trials of the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (i.e., trials 1–5; RAVLT; Majdan, Sziklas, & Jones-Gotman, 1996) and the learning trials of the 7/24 Spatial Recall Test (Rao, Hammeke, & McQuillen, 1984) remained poorer than those of controls at follow-up, Fs > 3.24, with neither group showing a significant improvement in performances across time, Fs < 1. In addition, while both groups showed improved performance at follow-up on the RAVLT long-delay free recall measure, F(1, 25) = 10.73, p < .01, η2 = .30, the TBI participants did not exhibit disproportionately improved performance on this memory measure, F = .23. These findings provide little support for arguing that the improved time estimation abilities of the TBI participants at follow-up reflect better episodic memory abilities.

Correlations with neuropsychological variables

We then conducted correlations and examined the relationship between time estimation ability, as measured by ratio scores reflecting the direction and magnitude of the error, and the neuropsychological measures shown in Table 1 at both baseline and follow-up. Because of the large number of correlations conducted, we used a more conservative alpha level of .01. The only correlation which reached statistical significance, a correlation at baseline between Trails B and the 60 s ratio score for the control group (r = −.65, p < .01), was caused by an outlier. The strongest correlations to emerge for the TBI participants were between the long-delay free recall trial of the RAVLT and the 45 s (r = .60, p < .05) and 60 s (r = .57, p < .05) ratio score at baseline, and between the learning trials of the 7/24 Spatial Memory Test and the 45 s (r = .58, p < .05) ratio score at baseline. These correlations were, however, in the unexpected direction of suggesting that better memory performance by the TBI participants resulted in poorer time estimates. No significant correlations emerged at follow-up between the neuropsychological measures and the ratio scores for either the TBI group (rs range = −.42 to .41) or the control group (rs range = −.48 to .44).

Correlations with injury characteristics

Correlations were also conducted for the TBI participants to examine the relationship between time estimation ability, as measured by the ratio score, and injury characteristics (i.e., coma duration, GCS score, duration of PTA, time since injury). No significant correlations emerged between either baseline or follow-up ratio scores and coma duration (rs range = −.20 to .12), GCS score (rs range = −.27 to .10), duration of PTA (rs range = −.00 to .36), or time since injury (rs range = −.04 to .42).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the recovery of time perception in individuals with moderate to severe TBI. Following the first year of recovery, we retested TBI and control participants from the Schmitter-Edgecombe and Rueda study (2008) on a prospective, verbal time estimation task that required participants to estimate filled durations of 10 s, 25 s, 45 s, and 60 s. Schmitter-Edgecombe and Rueda interpreted their findings that the TBI group produced normal or near normal estimates for intervals of short duration (i.e., 10 s and 25 s) but significantly underestimated intervals that exceeded working memory (i.e., 45 s and 60 s), as being due to episodic memory dysfunction. Consistent with their study, as well as with other prior research (Meyer & Levin, 1992; Perbal et al., 2003), the returning subset of TBI participants in this study performed similar to controls when estimating the 10 s time interval at baseline but was less accurate estimating the 45 s and 60 s time intervals. Unlike in the Schmitter-Edgecombe and Rueda (2008) study, however, this smaller subset of individuals with TBI was also found to significantly underestimate the 25 s interval at baseline.

One could argue that the 25 s interval is close to the time frame of working memory and may partly tap episodic memory abilities explaining the significant baseline group difference at the 25 s interval in the present study. Past studies have shown that timing intervals that approach 30 s may activate episodic memory abilities (e.g., Richards, 1973; Shaw & Aggleton, 1993). For example, HM (Richards, 1973), who experienced severe episodic memory impairment after surgical resection of the medial cortex bilaterally, showed inaccuracies estimating time longer than 20 s. Meyers and Levin (1992) also found that the TBI participants in their study who had the greatest difficulty estimating the 15 s duration also demonstrated the greatest memory impairment.

At follow-up testing, however, despite the presence of continued episodic memory impairment in the TBI group, there were no longer differences in the time estimates made by the participants with TBI and the controls. Instead, while the accuracy of the verbal time estimates of the TBI participants recovered to a level comparable to the control group, there was little notable recovery in the TBI group’s episodic memory performance. In addition, correlations at baseline between the memory measures and the 45 s and 60 s time estimation intervals unexpectedly suggested that better memory performance by the TBI participants resulted in poorer time estimates. The findings of the current study show a return of time estimation abilities during the first year of recovery from moderate to severe TBI; at follow-up the TBI group no longer perceived less time as having passed than actually had passed. The findings further indicate that, counter to the hypothesis put forth by Schmitter-Edgecombe and Rueda (2008), episodic memory dysfunction may not have played a significant causative role in the TBI groups’ underestimation of time for longer durations more acutely following injury. What, then, might account for the TBI participant’s underestimation of longer duration intervals acutely following injury, and for recovery in time perception abilities by the TBI participants?

A study by Perbal et al. (2003), which used production and reproduction methods and assessed time durations of 38 s or less, revealed that TBI participants showed similar levels of accuracy in time estimates but exhibited greater timing variability than controls. In the present study, however, at both baseline and follow-up testing the TBI participants were no more variable than control participants in their estimations of interval durations of similar length. Therefore, differences in response consistency cannot explain the poorer baseline time estimates of the TBI participants.

Zakay and Block (1997) proposed that an individual’s perception of time can be conceptualized as being influenced by both cognitive factors, such as attention and memory, and biological processes, such as an ‘internal clock.’ Therefore, deficits in other cognitive processes, such as attention, speeded processing, or executive functioning, may account for the TBI groups initially poorer time estimates. For example, attention has been implicated in temporal perception as time estimations have been found to shorten when attention is occupied by a cognitively demanding task (Burnside, 1971; Chaston & Kingstone, 2004; Zakay, 1990). Consistent with the recovery seen in time estimation abilities, significant recovery and improved performances at follow-up by the TBI participants were found on many of the neuropsychological measures that assessed attention, speeded processing and executive functioning skills. However, unlike time estimation accuracy, which returned to normal levels, the TBI participants continued to perform more poorly than controls on the measures of attention, speeded processing and executive functioning at one year post injury. In addition, no significant correlations were found between the neuropsychological tests assessing these skills and time estimation accuracy. It could, however, be argued that the concurrent counting task that was utilized to prevent subvocal rehearsal and minimize other monitoring strategies might have required the TBI participants to devote more of their attentional capacity or processing resources to the concurrent task at baseline as compared to follow-up, thereby resulting in shorter time estimates and poorer time estimation accuracy by the TBI group at baseline testing.

It is also possible that over the year time frame, individuals with TBI relearned or adjusted the verbal labels that define their subjective time. According to the attentional-gate model (Zakay & Block, 1996, 1997; Zakay, Block, & Tsal, 1999) after the time to be experienced is complete, the accumulated pulses are compared with learned time marking words for subjective time. Accuracy of verbal estimates depends on how experienced time relates to subjective time. An individual can adjust their verbal labels for experienced durations over time if an individual’s estimate is reinforced (Wearden, 2003). One limitation of the verbal estimation method is the reliance on a person’s “scaling” of time (Wearden, 2003). How an individual’s subjective time relates to a given duration of time determines how one applies a verbal label to time units. It could be argued that over the course of recovery, individuals with TBI may have relearned or adjusting subjective time to be more accurate to actual time units. Future research investigating time estimation in persons with TBI should consider using verbal estimation in conjunction with the reproduction methods. A study by Craik and Hay (1999) suggested that verbal estimation and production methods of assessing time may tap similar time perception mechanisms. The reproduction method, however, may be less influenced by the presence of an internal clock and more heavily influenced by cognitive functions (Ulbrich, Churan, Fink, & Wittmann, 2007), specifically working memory (Craik & Hay, 1999; Baudouin, Vanneste, Isingrini, & Pouthas, 2006). Utilizing more than one timing procedure would assist in teasing out which timing mechanisms are disrupted post-TBI.

Another possibility is that the TBI may have resulted in a temporary impairment in the ‘internal clock.’ Several models of the internal clock have also been proposed that are based on an interval clock that is not affected by attention (i.e., Oscillator-based model; e.g., Matell & Meck, 2000). In the Scalar Timing Model (Gibbon, 1977; Gibbon, Church, & Meck, 1984), a pacemaker-accumulator type mechanism is hypothesized to count the pulses generated by a pacemaker. An important premise of internal clock theories is that the magnitude and direction of errors should be consistent across the actual time durations to be estimated (Meck & Benson, 2002). Consistent with this possibility, although the TBI group exhibited improved ratio scores at follow-up, we did not find discontinuity in the magnitude of ratio scores across time intervals (i.e., 10 s, 25 s, 45 s, and 60 s) for either the TBI or control group at baseline or at follow-up in the present study.

Finally, multiple factors, such as medications, have been shown to influence the internal clock (Hancock, 1993). For example, medications such as psychostimulants and anticholinergics have been found to increase prospective time estimates, while benzodiazepines decrease duration judgments (Hicks, 1992). It is unclear to what extent, if at all, medications individuals with TBI were taking influenced their time estimation performance. Future research, which longitudinal follows TBI participants at closer intervals, will be needed to identify factors, such as medications, that may play a critical role in the recovery of time perception abilities following TBI.

Before concluding, we consider limitations to the present study. First, all TBI participants in the present study experienced a diffuse closed-head injury as a result of a moderate to severe TBI as documented in medical records. All the TBI participants were also Caucasian individuals between the ages of 15 to 55 and did not score below cut-off for dementia on a gross measure of cognitive functioning (i.e., TICSm). Since none of the TBI participants were in the demented range of functioning at the time of testing and were oriented, the results may not generalize to persons whose cognitive functioning is more impaired (cf. Meyers & Levin, 1992). Since all TBI participants were actively participating in inpatient rehabilitation at the time of the initial testing, these results may not generalize to TBI participants who did not participate in inpatient rehabilitation. In addition, the sensitivity of our ability to detect a relationship between time estimation and neuropsychological processes was limited to the specific neuropsychological tests that were administered. It is possible that the given tests were not sensitive to a neural mechanism that was impacted by TBI and recovered within the first year. Finally, although this research methodology provides a snapshot of participants’ time estimation abilities, the task used in this laboratory study were clinical instruments designed to assess prospective time estimation abilities under optimal conditions rather than real-world situations. Therefore, additional research is needed to better understand whether individuals with TBI would accurately estimate time of real-world situations (e.g., cooking).

In summary, this study used a prospective verbal time estimation paradigm to investigate the recovery of time estimation in individuals with moderate to severe TBI. Despite exhibiting greater underestimation for duration judgments 25 s or longer more acutely following injury, after 12 months of recovery, we found that the TBI participants were as accurate as controls estimating time durations up to 60 s. These results suggest a recovery of time estimation abilities in the first year of recovery following moderate to severe TBI; which likely has important positive implications for everyday activities given the significant roles that time perception plays in everyday life. It has also been suggested that episodic memory deficits may influence the accuracy of temporal perception for durations outside working memory in individuals with TBI (Levin & Meyers, 1992; Schmitter-Edgecome & Rueda, 2008) and other neurological populations (e.g., amnestic disorders, Kinsbourne, 2000; Mimura et al., 2000; Perbal et al., 2000; Richards, 1973; Williams, 1988). The results of this study suggest that some factor or factors associated with TBI, other than episodic memory impairment, play a more critical role in the recovery of time perception abilities following moderate to severe TBI.

Acknowledgments

Jonathan W. Anderson, Ph.D., Department of Psychology, Eastern Washington University, and Maureen Schmitter-Edgecombe, Ph.D., Department of Psychology, Washington State University. This study was partially supported by grant #R01 NS47690 from NINDS. We would like to thank Randi McDonald, Shital Pavawalla, Jennifer McWilliams, Michelle Nuegen, Matthew Wright, and Ellen Woo for their support in coordinating data collection. We would also like to thank the TBI participants and the members of the Head Injury Research Team for their help in collecting and scoring the data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/neu

References

- Anderson JW, Schmitter-Edgecombe M. Predictions of episodic memory following moderate to severe traumatic brain injury during inpatient rehabilitation. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2008;31:425–438. doi: 10.1080/13803390802232667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barona A, Reynolds CR, Chastain R. A demographically based index of premorbid intelligence for the WAIS-R. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:885–887. [Google Scholar]

- Baudouin A, Vanneste S, Isingrini M, Pouthas V. Differential involvement of internal clock and working memory in the production and reproduction of durations: A study on older adults. Acta Psychologica. 2006;121:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Hamsher K. deS, Sivan AB. Multilingual Aphasia Examination. 3rd ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Block RA. Models of psychological time. In: Block RA, editor. Cognitive Models of Psychological Time. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publisher; 1990. pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Block RA, Zakay D. Prospective and retrospective duration judgments: A meta-analytic review. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1997;4:184–197. doi: 10.3758/BF03209393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block RA, Zakay D, Hancock PA. Human aging and duration judgments: a meta-analytic review. Psychology and Aging. 1998;13:584–596. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.13.4.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonomano DV, Karmarkar UR. How do we tell time? The Neuroscientist. 2002;8:42–51. doi: 10.1177/107385840200800109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SW. Attentional resources in timing: interference effects in concurrent temporal and nontemporal working memory tasks. Perception and Psychophysics. 1997;59:1118–1140. doi: 10.3758/bf03205526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnside W. Judgment of short time intervals while performing mathematical tasks. Perception and Psychophysics. 1971;9:404–406. [Google Scholar]

- Cahoon RL. Physiological arousal and time estimation. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1969;28:259–268. doi: 10.2466/pms.1969.28.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaston A, Kingstone A. Time estimation: the effect of cortically mediated attention. Brain and Cognition. 2004;55:286–289. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chistensen BK, Colella B, Inness E, Hebert D, Monette G, Bayley M, et al. Recovery of cognitive function after traumatic brain injury: A multilevel modeling analysis of Canadian outcomes. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2008;89:S3–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craik FI, Hay JF. Aging and judgments of durations: Effects of task complexity and method of estimation. Perception & Psychophysiology. 1999;61:549–560. doi: 10.3758/bf03211972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Guger S, Roncadin C, Barnes M, Schachar R. Attentional-inhibitory control and social-behavioral regulation after childhood closed head injury: do biological, developmental, and recovery variables predict outcome? Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2001;7:683–692. doi: 10.1017/s1355617701766040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doob LW. Patterning of time. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Eagleman DM, Tse PU, Buonomano D, Janssen P, Nobre AC, Holcombe AO. Time and the brain: How subjective time relates to neural time. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:10369–10371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3487-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM, Ewing-Cobbs L, Miner ME, Levin HS, Eisenberg H. Behavioral changes after closed head injury in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:93–98. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraisse P. The Psychology of Time (J. Leith, Trans.) New York: Harper & Row; 1957/1963. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon J. Scalar expectancy theory and Weber’s law in animal timing. Psychological Review. 1977;84:279–325. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon J, Church RM, Meck WH. Scalar timing in memory. In: Gibbon J, Allan L, editors. Timing and Time Perception. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences; 1984. pp. 52–77. 423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock PA. Body temperature influence on time perception. Journal of General Psychology. 1993;120:197–216. doi: 10.1080/00221309.1993.9711144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks RE. Prospective and retrospective judgments of time: A neurobehavioral analysis. In: Macar F, Pouthas V, Friedman WJ, editors. Time, Action, and Cognition: Towards Bridging the Gap. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic; 1992. pp. 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks RE, Miller GW, Kinsbourne M. Prospective and retrospective judgments of time as a function of amount of information processed. American Journal of Psychology. 1976;89:719–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielhofner G. Temporal adaptation: A conceptual framework for occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1977;31:235–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King NS, Crawford S, Wenden FJ, Moss NEG, Wade DT, Caldwell FE. Measurement of post traumatic amnesia: How reliable is it? Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1997;62:38–42. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsbourne M. The role of memory in estimating time: a neuropsychological analysis. In: Conner LT, Obler LK, editors. Neurobehavior of language and cognition: studies of normal aging and brain damage. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. pp. 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsbourne M, Hicks RE. The extended present: Evidence from time estimation by amnesics and normals. In: Vallan G, Shallice T, editors. Neuropsychological impairments of short-term memory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 319–329. [Google Scholar]

- Levin HS, O’Donnell VM, Grossman RG. The Galveston Orientation and Amnesia Test: A practical scale to assess cognition after head injury. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1979;167:675–684. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197911000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht BA, Morganti JB, Nehrke M, Heiman G. Mediators of estimates of brief time intervals in elderly domiciled males. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1985;21:211–225. doi: 10.2190/rbyl-67qw-yjn0-elbq. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majdan A, Sziklas V, Jones-Gotman M. Performance of healthy subjects and patients with resection from the anterior temporal lobe on matched tests of verbal and visuoperceptual learning. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1996;18:416–430. doi: 10.1080/01688639608408998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marum KD, Macintryre J, Armstrong R. Heart-rate conditioning, time estimation, and arousal level: Exploratory study. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1972;34:244. doi: 10.2466/pms.1972.34.1.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matell MS, Meck WH. Neuropsychological mechanisms of interval timing behavior. BioEssays. 2000;22:94–103. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200001)22:1<94::AID-BIES14>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauk MD, Buonomano DV. The neural basis of temporal processing. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2004;27:304–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan TM, Jongen ELM, Greenwood RJ. Assessment of post-traumatic amnesia after severe closed head injury: Retrospective or prospective? Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1996;60:422–427. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.60.4.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH, Benson AM. Dissecting the brain’s internal clock: How frontal-striatal circuitry keeps time and shifts attention. Brain and Cognition. 2002;48:195–211. doi: 10.1006/brcg.2001.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers CA, Levin HS. Temporal perception following closed head injury. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, and Behavioral Neurology. 1992;5:28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Myers JL, Well AD. Research Design and Statistical Analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mimura M, Kinsbourne M, O’Conner M. Time estimation by patients with frontal lobe lesions and by Korsakoff amnesics. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2000;6:517–528. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700655017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichelli P, Venneri A, Molinari M, Tavani F, Grafman J. Precision and accuracy of subjective time estimation in different memory disorders. Cognitive Brain Research. 1993;1:87–93. doi: 10.1016/0926-6410(93)90014-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornstein RE. On the Experience of Time. Harmondsworth, GB: Penguin; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Perbal S, Coullet J, Azouvi P, Pouthas V. Relationship between time estimation, memory, attention, and processing speed in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:1599–1610. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(03)00110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal S, Pouthas V, Vander Linden M. Time estimation and amnesia: A case study. Neurocase. 2000;6:347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Polyukhov AM. Subjective time estimation in relation to age, health, and interhemispheric brain asymmetry. Zeitschrift fur Gerontologie. 1989;22:79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SM, Hammeke TA, McQuillen MP. Memory disturbance in chronic progressive multiple sclerosis. Archives of Neurology. 1984;41:625–631. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1984.04210080033010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SM, Mayer AR, Harrington DL. The evolution of brain activation during temporal processing. Nature Neuroscience. 2001;4:317–323. doi: 10.1038/85191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Richards W. Time reproduction by H. M. (1973) Acta Psychologica. 1973;37:279–182. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(73)90020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda AD, Schmitter-Edgecombe M. Time estimation abilities in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:179–188. doi: 10.1037/a0014289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitter-Edgecombe M, Rueda A. Time estimation and episodic memory following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2008;30:1–12. doi: 10.1080/13803390701363803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw C, Aggleton JP. The ability of amnesic subjects to estimate time intervals. Neuropsychologia. 1994;32:857–873. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderland A, Harris JE, Baddeley AD. Do laboratory tests predict everyday memory? A neuropsychological study. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1983;22:341–357. [Google Scholar]

- SuperLab Pro Beta Version Experimental Lab Software [Computer software] San Pedro, CA: Cedrus Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Computer-Assisted Research Design and Analysis. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor HG, Yeates KO, Wade SL, Drotar D, Stancin T, Minich N. A prospective study of short- and long-term outcome after traumatic brain injury in children: Behavior and Achievement. Neuropsychology. 2002;16:15–27. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.16.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. a practical scale. Lancet. 1974;13:81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulbrich P, Churan J, Fink M, Wittmann M. Temporal reproduction: Further evidence for two processes. Acta Psychologica. 2006;125:51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderploeg RD, Crowell TA, Curtiss G. Verbal learning and memory deficits in traumatic brain injury: Encoding, consolidation, and retrieval. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2001;23:185–195. doi: 10.1076/jcen.23.2.185.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wearen JH. Applying the scalar timing model to human time psychology: Progress and challenges. In: Helfrich H, editor. Time and Mind II: Information-Processing Perspectives. Gottingen, DE: Hogrefe & Huber; 2003. pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wearden JH, Penton-Voak IS. Feeling the heat: Body temperature and the rate of subjective time, revisited. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1995;48B:129–141. doi: 10.1080/14640749508401443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM. Memory disorders and subjective time estimation. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1988;11:713–723. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DH, Levin HS, Eisenberg HM. Mild head injury classification. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:422–428. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199009000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakay D. The evasive art of subjective time measurement: Some methodological dilemmas. In: Block RA, editor. Cognitive models of psychological time. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1990. pp. 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zakay D, Block RA. The role of attention in time estimation processes. In: Pastor MA, Artieda J, editors. Time, internal clocks and movement. Amsterdam: Elsevier, North Holland; 1996. pp. 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- Zakay D, Block RA. Temporal Cognition. Current Directions in Psychological Research. 1997;6:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zakay D, Block RA, Tsal Y. Prospective duration estimation and performance. In: Gopher D, Koriat A, editors. Attention and Performance XVII: Cognitive Regulation of Performance: Interaction of Theory and Application. Attention and Performance. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 1999. pp. 557–580. [Google Scholar]