Abstract

Objectives. We sought to determine how part-year and full-year gaps in health insurance coverage affected working-aged persons with chronic health care needs.

Methods. We conducted multivariate analyses of the 2002–2004 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey to compare access, utilization, and out-of-pocket spending burden among key groups of persons with chronic conditions and disabilities. The results are generalizable to the US community-dwelling population aged 18 to 64 years.

Results. Among 92 million adults with chronic conditions, 21% experienced at least 1 month uninsured during the average year (2002–2004). Among the 25 million persons reporting both chronic conditions and disabilities, 23% were uninsured during the average year. These gaps in coverage were associated with significantly higher levels of access problems, lower rates of ambulatory visits and prescription drug use, and higher levels of out-of-pocket spending.

Conclusions. Implementation of health care reform must focus not only on the prevention of chronic conditions and the expansion of insurance coverage but also on the long-term stability of the coverage to be offered.

Approximately 46 million Americans were uninsured in 2006–2007.1 However, measures such as this one are based upon the number of individuals without coverage on a particular day; consequently, these measures record a person as insured even if that individual may have experienced a period without coverage directly preceding or following the day of measurement. The result is an undercount of persons experiencing brief spells uninsured.2 Individuals frequently move into and out of coverage over time,3,4 and persons with chronic conditions and disabilities may be particularly sensitive to the effects of even these brief periods without insurance. A number of factors have caused persons with ongoing health care needs to have difficulty obtaining and maintaining stable coverage, such as taking a job without health benefits, job loss or transition, divorce, means testing, disability determination, or waiting periods for public coverage.5–8 A growing body of research documents how being uninsured can affect persons with chronic conditions,9–13 and other studies have separately examined the experiences that people with disabilities have when uninsured.7,8,14–16 However, these are not mutually exclusive populations, and the extent and effects of insurance coverage gaps in these groups are not well differentiated in the available literature.

Existing research cautions us that insurance coverage is a dynamic process,2–4 but most current studies of these groups employ point-in-time estimates of insurance coverage or limit the analysis to the long-term uninsured, potentially underestimating the extent of coverage interruptions. Furthermore, these are population groups with much to gain (or lose) as health care reform is implemented in the years to come.

Unlike individuals who require simple routine care and screenings, adults with chronic health care needs have conditions that persist over time, sometimes necessitating the continuing use of a range of costly health care services.17 In addition, persons with chronic conditions frequently have multiple long-term conditions18 and may also develop additional acute conditions over time.19 Although this accumulation of medical conditions is well documented in elderly populations,20 roughly half of the working-aged population also has at least 1 chronic condition.21 About a quarter of these persons will also report some degree of disability that may affect work and other types of community participation, as well as such fundamental activities as independently dressing, bathing, or preparing a meal.18,22

Regardless of whether an individual has a single chronic condition or several, or whether that individual has a disability or not, the effort required to manage ongoing health care needs over time can be substantial, particularly in a system as specialized as ours.23,24 Studies of persons with chronic conditions18,19,21 and disabilities7,25,26 document high utilization rates of many types of care in numerous different settings. Hence, the primary concerns for many persons with chronic conditions and disabilities include how to arrange, coordinate, and pay for care from multiple providers at the same time.18 Indeed, even among the fully insured, out-of-pocket spending rises in a linear fashion with the number of chronic conditions reported.27

In light of these concerns, we investigated the extent of insurance coverage gaps among working-aged adults with chronic conditions and disabilities. Although these populations have historically been studied separately, we used a combined approach because of their shared needs for ongoing health care services. We examined the prevalence of part-year and full-year insurance gaps in 3 subgroups of these adults on the basis of presence and extent of disability. We then analyzed how this instability in coverage could affect access to general medical services and prescription medications, rates of ambulatory health care visits and prescription fills, and out-of-pocket spending for health care services.

METHODS

We pooled annual data files from the 2002–2004 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Household Component and related files for medical conditions and medical events during those years.28,29 All results reported take the form of weighted, averaged estimates for the period of 2002–2004, which, for brevity, we call the “year.” The final sample size was 58 408, which was the basis of our estimate of approximately 177 million community-dwelling working-aged adults in the United States. To identify persons with ongoing needs for care, we adapted a well-validated list of chronic medical conditions27 and applied it to the International Classification of Disease codes provided in MEPS.19,22,30 Each medical or mental health condition on this list is expected to last at least 12 months and to result in a need for ongoing intervention (including regularly prescribed medications, therapies provided by health professionals, specialized medical equipment, or protocols affecting diet or physical activity) or limitations (including limitations on age-appropriate task performance, activities of daily living [ADL], instrumental activities of daily living [IADL], or social interactions). Individuals reporting 1 or more of the listed conditions were flagged as having a chronic condition. Individuals without these conditions comprised a contrast group that reported either no medical conditions at all or conditions not expected to result in a lasting need for medical intervention.

To further assess disability among those with chronic conditions, we used the limitation measures in the MEPS in the following domains: limitations in physical functioning; cognitive difficulties; sensory impairment; limitations in activities such as work, housework, or school; social limitations; use of assistive devices; and limitations in ADL or IADL (the need for help or supervision with activities such as dressing, bathing, meals, or taking medications). We then categorized 4 mutually exclusive groups of adults: those without chronic conditions (the contrast group), and 3 subgroups of adults with at least 1 chronic condition—those without self-reported limitations, those reporting limitations other than ADL or IADL limitations, and those needing help or supervision with ADL or IADL. (A list of the most prevalent health conditions by analytic group is presented in Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.)

Measures

We characterized insurance both with regard to status (insured all year; uninsured part of the year, including uninsured for 1–5 or 6–11 months; and uninsured all year, meaning 12 months without coverage) and source (any private insurance, including any primary or dependent coverage by employer or union group, another group, or individual-market sources; and public only, including Medicare, Medicaid, TRICARE, or other government-sponsored coverage).

For general medical care services and for prescription medications, we examined the percentage self-reporting delay or nonreceipt during the year, reflecting access to care. Next, we analyzed differences in 2 measures of service utilization: total ambulatory health care visits and number of prescription medication fills during the year. Last, we measured the percentage of respondents reporting a high health care service burden, defined as annual out-of-pocket spending for medical care by the individual (excluding premiums) that met or exceeded 15% of family income.31 “Family” was defined on the basis of Health Insurance Eligibility Units, a definition of family used in MEPS to group persons who would likely be covered together under an insurance plan (e.g., spouses and their dependents, including children away at school up to age 24 years). Our multivariate models included controls for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and poverty status (based on the federal poverty level measure provided with the MEPS-HC data files).

Statistical Analysis

We first examined the population distributions of working-aged persons with and without chronic conditions by analytic group, insurance status, and insurance sources. We then calculated weighted, average annual estimates (2002–2004) of the access, utilization, and out-of-pocket spending burden measures, on the basis of analytic group and insurance status. We computed statistical significance of differences in these measures by using the pairwise t test, while controlling the false discovery rate32 for multiple comparisons. We next fit multivariate models to the data to compare differences in the outcome measures (access, utilization, and out-of-pocket spending burden), on the basis of insurance status, analytic group, and their interaction, while controlling for the covariates described earlier. The contrast group (no chronic conditions) and those insured all year were designated as the reference groups.

We used logistic regression for the 2 models pertaining to access. The models pertaining to service use were fit in 2 parts: logistic regressions were used to predict any use in the first part, and generalized estimating equations with a log link function were used to predict average annual visits among those with at least 1 medical visit or prescription fill. Lastly, after controlling the covariates and family size, we used logistic regression to model the percentage reporting high health care service burden, and we calculated 2-way predicted marginal estimates. We used Taylor-series linearization for variance estimation throughout.

RESULTS

Among all working-aged adults, 28 million (16%) remained uninsured for all 12 months, and an additional 21 million (12%) reported part-year coverage, as shown in Table 1. Among those with part-year coverage, there was an even split between persons reporting a period of 1 to 5 months without coverage versus those reporting a period lasting 6 to 11 months, with a mean of 5.2 months uninsured. The proportion losing coverage and not regaining it by year's end was about 40%, as was the proportion gaining and maintaining coverage through the year's end. The remaining 20% moved both into and out of coverage in a single year. (Additional analyses of sociodemographic and health-status differences on the basis of insurance status are presented in Table B, available as a supplement online at http://www.ajph.org.)

TABLE 1.

Pooled Annual Estimates of Chronic Conditions, Disabilities, Demographics, and Insurance Status Among US Adults Aged 18–64 Years: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002–2004

| Measures | All Persons | Without Chronic Condition | With Chronic Condition | Chronic Condition, No Disability | Chronic Condition, Disability Not Affecting ADL or IADL | Chronic Condition, Disability Affecting ADL or IADL |

| All insurance statuses | ||||||

| Sample size | 58 408 | 29 237 | 29 171 | 20 399 | 6472 | 2300 |

| Population size, millions (95% CI) | 176.81 (169.55, 184.07) | 85.30 (81.32, 89.28) | 91.52 (87.78, 95.26) | 66.92 (63.92, 69.92) | 18.70 (17.67, 19.73) | 5.90 (5.42, 6.38) |

| % all persons (SE) | 100 | 48.24 (0.39) | 51.76 (0.39) | 37.85 (0.36) | 10.57 (0.25) | 3.34 (0.13) |

| % all persons with ≥ 1 chronic condition (SE) | N/A | N/A | 100 | 73.12 (0.53) | 20.43 (0.43) | 6.45 (0.24) |

| Age, y, mean (SE) | 40.75 (0.11) | 36.65 (0.12)bcde | 44.58 (0.14)a | 43.18 (0.16)ade | 48.47 (0.21)ac | 48.16 (0.35)ac |

| Female, % (SE) | 51.00 (0.25) | 44.56 (0.45)bcde | 56.99 (0.33)a | 56.19 (0.40)ade | 58.76 (0.89)ac | 60.53 (1.44)ac |

| Insured all year | ||||||

| Sample size | 38 685 | 16 712 | 21 973 | 15 410 | 4747 | 1816 |

| Population size, millions (95% CI) | 127.63 (122.02, 133.24) | 55.28 (52.53, 58.03) | 72.35 (69.16, 75.54) | 53.46 (50.84, 56.08) | 14.21 (13.39, 15.03) | 4.68 (4.29, 5.07) |

| % analytic group (SE) | 72.18 (0.44) | 64.81 (0.56)bcde | 79.05 (0.44)a | 79.89 (0.48)ad | 75.98 (0.74)ace | 79.27 (1.24)ad |

| Any private sources of insurance, % (SE) | 90.54 (0.36) | 93.65 (0.36)bcde | 88.17 (0.47)a | 95.06 (0.29)ade | 75.04 (1.04)ace | 49.22 (1.88)acd |

| Public sources of insurance only, % (SE) | 9.46 (0.36) | 6.35 (0.36)bcde | 11.83 (0.47)a | 4.94 (0.29)ade | 24.96 (1.04)ace | 50.78 (1.88)acd |

| Uninsured part year | ||||||

| Sample size | 7593 | 4235 | 3358 | 2318 | 786 | 254 |

| Population size, millions (95% CI) | 21.14 (20.04, 22.24) | 11.48 (10.77, 12.19) | 9.66 (9.11, 10.21) | 6.82 (6.37, 7.27) | 2.17 (1.95, 2.39) | 0.67 (0.54, 0.80) |

| Months uninsured, mean (SE) | 5.20 (0.05) | 5.27 (0.06) c | 5.11 (0.07) | 5.05 (0.08)a | 5.26 (0.14) | 5.25 (0.23) |

| 1–5 mo uninsured, % (SE) | 6.73 (0.14) | 7.40 (0.20)bce | 6.11 (0.18)a | 5.97 (0.20)a | 6.72 (0.36) | 5.79 (0.65)a |

| 6–11 mo uninsured, % (SE) | 5.22 (0.12) | 6.06 (0.19)bcd | 4.44 (0.14)a | 4.22 (0.16)a | 4.90 (0.35)a | 5.50 (0.65) |

| 1–11 mo uninsured, % (SE) | 11.96 (0.20) | 13.46 (0.29)bcde | 10.56 (0.22)a | 10.19 (0.26)a | 11.62 (0.51)ac | 11.29 (0.95)a |

| Gaining and maintaining coverage, % (SE) | 40.19 (0.71) | 39.52 (1.00) | 40.98 (1.01) | 41.21 (1.15) | 39.38 (2.00) | 43.81 (3.76) |

| Losing and not regaining coverage, % (SE) | 39.81 (0.74) | 40.75 (0.97) | 38.69 (0.98) | 38.46 (1.09) | 40.12 (1.97) | 36.33 (3.71) |

| Multiple transitions during year, % (SE) | 20.01 (0.67) | 19.73 (0.88) | 20.34 (0.85) | 20.33 (0.97) | 20.51 (1.79) | 19.87 (2.95) |

| Uninsured all year | ||||||

| Sample size | 12 130 | 8290 | 3840 | 2 671 | 939 | 230 |

| Population size, millions (95% CI) | 28.04 (26.48, 29.60) | 18.53 (17.33, 19.73) | 9.51 (8.85, 10.17) | 6.64 (6.16, 7.12) | 2.32 (2.08, 2.56) | 0.56 (0.46, 0.66) |

| % analytic group (SE) | 15.86 (0.35) | 21.73 (0.49)bcde | 10.39 (0.34)a | 9.92 (0.36)ad | 12.40 (0.53)ace | 9.44 (0.75)ad |

Note. ADL = activities of daily living; CI = confidence interval; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; SE = standard error. We recorded significant differences (P < .05) after controlling the false discovery rate. All results are weighted and averaged to represent the US population during the period 2002–2004, which, for brevity, we call the “year.”

Differs significantly from the estimate for persons without chronic conditions.

Differs significantly from the estimate for persons with chronic conditions.

Differs significantly from the estimate for persons with a chronic condition and no disability.

Differs significantly from the estimate for persons with a chronic condition and a disability not affecting ADL or IADL.

Differs significantly from the estimate for persons with a chronic condition and a disability affecting ADL or IADL.

We identified 92 million working-aged adults with chronic health care needs in the US population. They were older, more highly educated, more likely to be female and non-Hispanic White, and no less likely to be in poverty than were persons without chronic conditions (Table C, available at http://www.ajph.org). They reported poorer overall health, with a mean of 2.1 chronic conditions and 2.6 acute conditions reported during the year. These figures are much higher than those reported among persons without chronic conditions (mean of 1.3 acute conditions). Among those with chronic conditions, the 2 subgroups with disabilities were older, more likely to be female, more likely to be Black, less well-educated, and more likely to be poor than were the 67 million persons without disabilities. Both disability groups scored worse on the health-related measures than did nondisabled adults with chronic conditions. The group with limitations in ADL or IADL (5.9 million persons) stood out in this regard: they averaged 3.5 chronic conditions per person, and 79% reported fair to poor overall health.

Coverage Gaps

Adults without chronic conditions had the largest percentages uninsured at any time during the year, primarily owing to the large numbers of individuals who were uninsured for all 12 months. However, we also found large numbers of uninsured persons with chronic conditions; approximately 10 million were uninsured all 12 months, and another 10 million were uninsured for part of the year. In total, 21% of adults with chronic conditions reported being uninsured for 1 or more months during the year.

Among those with chronic conditions, persons with disabilities were just as vulnerable (or slightly more vulnerable) to coverage gaps as were persons without disabilities. In particular, persons with chronic conditions and disabilities that did not affect ADL or IADL were less likely to report a full 12 months of coverage during the year than were individuals with chronic conditions who did not report a disability. Among persons reporting part-year gaps, we found no group differences in the percentages reporting that they had gained or lost coverage during the year. Further, in every group analyzed, approximately 20% of those with part-year gaps reported multiple transitions during the year involving both gains and losses of coverage.

Table 1 documents the increasingly important role of public coverage sources for adults with chronic conditions and disabilities. Among those who were insured the entire year, less than 5% of adults with chronic conditions and no disability had coverage exclusively from public sources. In contrast, this figure rose to more than 50% among persons with chronic conditions and disabilities that affected ADL or IADL.

Access, Utilization, and Out-of-Pocket Spending Burden

Table 2 provides average annual estimates of the percentages reporting delay in or nonreceipt of general medical services and prescription medications, rates of mean ambulatory visits and prescription fills, and out-of-pocket spending burden, on the basis of analytic group and insurance status. The results across all of these analyses can be summarized as follows:

TABLE 2.

Pooled Annual Estimates of Health Care Access, Utilization, and Out-of-Pocket Spending Burden Among US Adults Aged 18–64 Years, by Insurance Status: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002–2004

| Measures | Without Chronic Condition | With Chronic Condition | Chronic Condition, No Disability | Chronic Condition, Disability Not Affecting ADL or IADL | Chronic Condition, Disability Affecting ADL or IADL |

| Persons reporting delaying or not receiving general medical services, % (SE) | |||||

| Insured all year | 2.18 (0.15)xyz | 6.43 (0.27)xyz | 4.12 (0.23)xyz | 12.06 (0.64)xyz | 15.75 (1.08)xyz |

| Uninsured 1–5 mo | 4.81 (0.57)wz | 13.00 (0.91)wyz | 8.78 (0.88)wyz | 22.37 (2.64)wyz | 28.03 (5.18)wy |

| Uninsured 6–11 mo | 6.40 (0.69)w | 22.35 (1.40)wx | 14.49 (1.36)wx | 35.51 (3.36)wx | 53.83 (5.15)wxz |

| Uninsured all year | 6.67 (0.39)wx | 20.42 (0.98)wx | 14.95 (1.08)wx | 31.78 (2.00)wx | 38.19 (3.87)wy |

| Annual ambulatory health care visits, mean (SE) | |||||

| Insured all year | 2.85 (0.07)xyz | 9.50 (0.14)xyz | 6.94 (0.12)xyz | 15.07 (0.39)xyz | 21.79 (0.86)xyz |

| Uninsured 1–5 mo | 2.42 (0.14)wz | 7.67 (0.41)wyz | 5.73 (0.37)wyz | 11.60 (1.04)wz | 15.98 (1.93)w |

| Uninsured 6–11 mo | 2.02 (0.14)wz | 5.98 (0.35)wxz | 4.31 (0.31)wx | 8.98 (0.93)w | 12.01 (1.44)w |

| Uninsured all year | 1.07 (0.07)wxy | 4.91 (0.25)wxy | 3.56 (0.24)wx | 6.89 (0.54)wx | 12.66 (1.63)w |

| Persons reporting delaying or not receiving prescription medications, % (SE) | |||||

| Insured all year | 0.80 (0.10)xyz | 5.84 (0.21)xyz | 3.67 (0.19)xyz | 10.75 (0.52)xyz | 15.80 (1.00)yz |

| Uninsured 1–5 mo | 1.78 (0.30)wz | 10.12 (0.85)wyz | 5.94 (0.71)wyz | 20.18 (2.52)wy | 22.12 (4.92)y |

| Uninsured 6–11 mo | 2.81 (0.44)w | 18.81 (1.41)wxz | 12.29 (1.42)wx | 29.38 (2.97)wx | 45.58 (5.61)wx |

| Uninsured all year | 2.64 (0.26)wx | 14.00 (0.86)wxy | 9.08 (0.91)wx | 22.87 (1.62)w | 35.80 (4.45)w |

| Annual prescription medication fills, mean (SE) | |||||

| Insured all year | 2.07 (0.06)xyz | 18.17 (0.28)xyz | 12.76 (0.20)xyz | 29.09 (0.67)xyz | 46.73 (1.62)xyz |

| Uninsured 1–5 mo | 1.67 (0.10)wyz | 12.63 (0.52)wz | 9.08 (0.38)wz | 19.54 (1.51)wz | 28.71 (2.52)w |

| Uninsured 6–11 mo | 1.17 (0.07)wxz | 11.88 (0.59)wz | 8.11 (0.48)w | 17.73 (1.50)w | 28.18 (3.96)w |

| Uninsured all year | 0.76 (0.05)wxy | 10.17 (0.40)wxy | 7.05 (0.32)wx | 15.23 (0.90)wx | 26.21 (2.75)w |

| Persons spending 15% or more of family income on health care services, % (SE) | |||||

| Insured all year | 1.12 (0.10)yz | 4.52 (0.20)xyz | 2.04 (0.13)xyz | 8.61 (0.57)xyz | 20.42 (1.23)yz |

| Uninsured 1–5 mo | 2.04 (0.46)z | 6.78 (0.63)wyz | 3.97 (0.53)wyz | 12.88 (1.72)wyz | 17.12 (4.21)yz |

| Uninsured 6–11 mo | 2.87 (0.46)w | 12.62 (1.06)wxz | 7.29 (0.94)wxz | 21.47 (3.09)wx | 34.08 (5.81)wxz |

| Uninsured all year | 3.57 (0.30)wx | 16.60 (0.77)wxy | 11.04 (0.84)wxy | 24.16 (1.67)wx | 51.48 (4.34)wxy |

Note. ADL = activities of daily living; CI = confidence interval; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living. All results reported are from the period 2002–2004, which, for brevity, we call the “year.” We recorded significant differences (P < .05) after controlling the false discovery rate.

Differs significantly from the estimate for persons insured all year.

Differs significantly from the estimate for persons uninsured 1–5 mo during the year.

Differs significantly from the estimate for persons uninsured 6–11 mo during the year.

Differs significantly from the estimate for persons uninsured all year.

In each separate insurance status category, persons with chronic conditions reported more ambulatory visits, more prescription drug fills, greater access difficulties, and higher out-of-pocket spending burden than did persons without chronic conditions, particularly if they also reported a disability (tests of significance presented in Table D, available at http://www.ajph.org).

In virtually all instances and in all analytic groups, persons with even the shortest period uninsured (1–5 months) reported significantly fewer ambulatory visits and prescription fills, greater access difficulties, and higher out-of-pocket spending burden than did the continuously insured.

The largest gross differences in access, utilization, and out-of-pocket spending burden that we observed on the basis of insurance status were found among those reporting disabilities.

Multivariate Findings

To determine whether the differences in these estimates persisted after covariates were controlled, we fit logistic regression models to the 2 access measures and constructed 2-part models for the 2 measures of utilization, as shown in Table 3. For access to general medical services and prescription medications, we found that even after we controlled the covariates, persons with chronic conditions reported greater access problems than did persons without chronic conditions, especially when they also reported disabilities. These models also confirmed that persons with either part-year or full-year coverage gaps were more likely to report access problems than were the continuously insured. The interaction terms between analytic group and insurance coverage proved nonsignificant and were thus omitted in the final models.

TABLE 3.

Pooled Annual Estimates From Multivariate Models of Access to and Utilization of Medical Care Services Among US Adults Aged 18–64 Years, by Chronic Condition Status, Disability Status, Insurance Gaps, and Covariates: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002–2004

| Medical Care Delayed or Not Received, OR (95% CI) | Any Ambulatory Care Visit During Year, OR (95% CI) | Among Persons With Ambulatory Care Visits, IDR (95% CI) | Prescription Medications Delayed or Not Received, OR (95% CI) | Any Prescription Fills During Year, OR (95% CI) | Among Persons With Prescription Fills, IDR (95% CI) | |

| Age, y | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) | 1.01* (1.01, 1.01) | 1.01* (1.01, 1.01) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | 1.01* (1.00, 1.01) | 1.02* (1.02, 1.02) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 1.35* (1.24, 1.48) | 2.62* (2.48, 2.76) | 1.29* (1.23, 1.34) | 1.37* (1.24, 1.51) | 2.42* (2.29, 2.56) | 1.14* (1.10, 1.18) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.58* (0.50, 0.68) | 0.62* (0.57, 0.67) | 0.86* (0.80, 0.93) | 0.77* (0.65, 0.90) | 0.71* (0.66, 0.77) | 0.94* (0.88, 0.99) |

| Non-Hispanic other/multiple race | 0.87 (0.70, 1.06) | 0.72* (0.64, 0.81) | 0.91* (0.83, 0.99) | 0.89 (0.71, 1.10) | 0.62* (0.55, 0.69) | 0.85* (0.78, 0.93) |

| Hispanic, any race | 0.64* (0.54, 0.76) | 0.69* (0.63, 0.75) | 0.91* (0.86, 0.96) | 0.64* (0.55, 0.75) | 0.67* (0.62, 0.72) | 0.80* (0.76, 0.86) |

| Education | ||||||

| High school diploma/GED or greater (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No high school diploma/GED | 0.95 (0.84, 1.06) | 0.83* (0.77, 0.89) | 0.81* (0.76, 0.87) | 0.93 (0.81, 1.06) | 0.90* (0.83, 0.97) | 0.99* (0.94, 1.03) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married all year (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Single any time during year | 1.48* (1.33, 1.64) | 0.93* (0.87, 0.99) | 1.02 (0.97, 1.06) | 1.32* (1.20, 1.46) | 0.90* (0.84, 0.95) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.07) |

| Family income | ||||||

| High (≥ 400% FPL; Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Middle (200%–399% FPL) | 1.22* (1.08, 1.39) | 0.85* (0.80, 0.90) | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) | 1.45* (1.27, 1.66) | 0.98 (0.92, 1.04) | 1.09* (1.05, 1.13) |

| Low (125%–199% FPL) | 1.40* (1.17, 1.67) | 0.80* (0.73, 0.88) | 0.89* (0.84, 0.95) | 1.92* (1.63, 2.26) | 0.95 (0.86, 1.05) | 1.17* (1.11, 1.24) |

| Negative/poor/near poor (< 125% FPL) | 1.55* (1.32, 1.82) | 0.78* (0.71, 0.85) | 1.03 (0.95, 1.11) | 2.17* (1.84, 2.56) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.11) | 1.33* (1.25, 1.42) |

| Chronic condition and disability status | ||||||

| No chronic condition (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Chronic condition, no disability | 2.04* (1.83, 2.26) | 5.11* (4.73, 5.52) | 1.54* (1.46, 1.62) | 4.01* (3.52, 4.56) | 11.03* (10.17, 11.95) | 2.54* (2.42, 2.67) |

| Chronic condition, disability not affecting ADL or IADL | 5.76* (5.03, 6.59) | 14.89* (12.57, 17.65) | 3.07* (2.87, 3.29) | 10.80* (9.18, 12.71) | 22.62* (19.09, 26.81) | 4.69* (4.41, 4.99) |

| Chronic condition, disability affecting ADL or IADL | 7.65* (6.48, 9.04) | 21.48* (15.96, 28.90) | 4.55* (4.15, 4.99) | 15.54* (12.90, 18.71) | 37.11* (26.67, 51.64) | 7.19* (6.60, 7.84) |

| Insurance coverage status | ||||||

| Insured all year (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Uninsured part year (1–11 mo) | 2.48* (2.18, 2.82) | 0.85* (0.77, 0.92) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.07) | 2.17* (1.88, 2.50) | 0.86* (0.79, 0.95) | 0.88* (0.81, 0.95) |

| Uninsured all year | 3.18* (2.82, 3.58) | 0.35* (0.32, 0.38) | 0.86* (0.77, 0.96) | 2.27* (1.95, 2.64) | 0.44* (0.40, 0.48) | 0.76* (0.68, 0.84) |

| Chronic status × insurance status | ||||||

| Chronic condition, no disability, uninsured part year | NS | 0.72* (0.61, 0.85) | 0.89 (0.78, 1.02) | NS | 0.64* (0.54, 0.77) | 0.92 (0.83, 1.02) |

| Chronic condition, no disability, uninsured all year | NS | 0.79* (0.69, 0.90) | 0.87 (0.75, 1.02) | NS | 0.73* (0.54, 0.73) | 0.97 (0.84, 1.12) |

| Chronic condition, disability not affecting ADL or IADL, uninsured part year | NS | 0.44* (0.30, 0.64) | 0.79* (0.68, 0.91) | NS | 0.54* (0.39, 0.74) | 0.84* (0.73, 0.97) |

| Chronic condition, disability not affecting ADL or IADL, uninsured all year | NS | 0.46* (0.35, 0.60) | 0.70* (0.58, 0.85) | NS | 0.41* (0.31, 0.54) | 0.87 (0.73, 1.03) |

| Chronic condition, disability affecting ADL or IADL, uninsured part year | NS | 0.42* (0.22, 0.82) | 0.70* (0.57, 0.85) | NS | 0.51 (0.24, 1.10) | 0.76* (0.63, 0.91) |

| Chronic condition, disability affecting ADL or IADL, uninsured all year | NS | 0.43* (0.26, 0.72) | 0.80 (0.60, 1.07) | NS | 0.51* (0.28, 0.92) | 0.82 (0.64, 1.05) |

Note. ADL = activities of daily living; CI = confidence interval; FPL = federal poverty level; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; IDR = incidence density ratio; NS = terms omitted, not significant; OR = odds ratio. All results reported are from the period 2002–2004, which, for brevity, we call the “year.”

*P < .05.

With regard to utilization, the 2-part models of ambulatory visits and prescription fills demonstrated that persons with gaps in coverage reported significantly lower utilization in all 4 analytic groups than did persons with continuous coverage. In addition, the interaction terms between the analytic groups and their insurance statuses revealed that these gaps may have affected the groups disproportionately, with greater reductions in use seen among those with chronic conditions (and disabilities) than among persons without them.

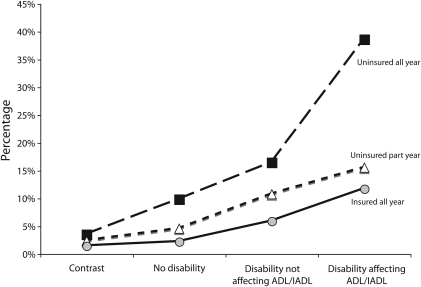

When we modeled the percentage of individuals who reported spending 15% or more of their family income on medical goods and services (excluding insurance premiums), we found that persons with either part-year or year-long coverage gaps were more likely to report health care service burdens in excess of 15% of family income compared with persons with continuous coverage (Figure 1). This was true in all groups except for the group with limitations in ADL or IADL, where part-year gaps did not reach significance (P = .15). In the contrast group, regarding the percentage with high out-of-pocket burden, the estimated difference in size between those insured all year and those uninsured all year is a bit more than 2 percentage points. By comparison, for persons with limitations in ADL or IADL, the size difference between those insured all year and those uninsured all year was in excess of 25 percentage points. In addition, even when persons with disabilities were insured all year long, nontrivial percentages of this group still reported high out-of-pocket burdens, suggesting that some members of these groups may be underinsured.

FIGURE 1.

Percentages of US adults aged 18–64 years spending 15% or more of family income on health care services, by analytic group and insurance coverage status: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002–2004.

Note. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living. Data are pooled annual estimates. Covariate-controlled predicted marginal rates are presented. Predicted marginal estimates were computed from a logistic regression model fit on the basis of analytic group, insurance coverage status, the interaction of those 2 variables, and the following covariates: age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and the number of persons in the health insurance eligibility unit.

DISCUSSION

We identified 19 million working-aged adults with chronic health care needs who reported lacking coverage at some point during the year. Among the 2 subgroups with disabilities, we found that more than 1 in 5 persons reported a coverage gap. When our findings are compared with studies that relied on short chronic condition lists12,33 or that did not evaluate brief coverage interruptions,7,10,12,33,34 they suggest that the problem of uninsurance may be more widespread in these populations than previously recognized. Furthermore, these coverage gaps were often associated with access problems, reductions in ambulatory visits and prescription drug use, and higher out-of-pocket spending burdens, particularly for persons with disabilities.

Policy Implications

The passage of health care reform in the form of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) reflects a growing consensus that health care in the United States must be reoriented toward prevention, better management of chronic conditions, and greater attention to the health and community-based support of persons with disabilities.21,23,35–37 PPACA addresses many of these issues directly through enhanced public health funding, medical home initiatives, coverage for preventive health visits, and several programs for community-based services for people with disabilities. The success of this agenda will depend on reform of both public programs and private insurance practices to ensure that coverage remains steadfast during periods of unemployment, loss of income, or ill health.

Indeed, the PPACA makes many promises to persons with chronic conditions and disabilities who are currently uninsured or who have struggled to maintain stable coverage over time. Complementing the individual mandate, these promises cover wide ground, including the extension of Medicaid benefits to all working-aged adults whose income is less than 133% of the federal poverty level, protections for persons with preexisting conditions, guaranteed issue and renewal in the private market, extension of child coverage up to age 26 years, temporary high-risk pools to grant relief to the currently uninsurable, and a longer-term plan to create subsidized, state-based insurance exchanges. Taken together, this is a large package of incremental changes that may create many new pathways to coverage. Given time, the PPACA may further dissolve the problematic link between employment and insurance that historically left many with chronic conditions “job-locked”38 and that created significant work disincentives for people with disabilities, though it may not eliminate that link entirely.39

Assuming the PPACA survives the legal challenges now arising in several states, delivering on the promise of stable insurance coverage will still be a complex matter. First, there remain notable gaps in the law itself. Congress opted to leave in place the 2-year waiting period for Medicare coverage for persons with disabilities subsequent to receipt of Social Security disability insurance. Waiting periods are also evident for long-term services and community supports for people with disabilities. Moreover, the law allows private insurers a delay of up to 90 days before newly issued coverage must go into effect. In the short term, extending the federal COBRA subsidies that were initiated under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act might provide some relief to persons trying to avoid a gap in coverage, but in the longer term, these waiting periods may require legislative redress.

Second, these new options for coverage may be welcomed by consumers, but they may also add complexity to an already complex system. Depending upon how each state implements these new mechanisms, persons with chronic health care needs may find it a lengthy process to find and secure the coverage that fits their current circumstances and provides the benefits required. This may be a special concern for persons whose functional limitations, health problems, or mental health conditions cause serial disruptions in employment or income, or interfere with their ability to self-advocate. To avoid delays, such consumers may require information in accessible formats40 and counseling or case management to sort through their options. Aging and Disability Resource Centers, which receive enhanced funding under PPACA, may provide a key node of infrastructure for such persons. In addition, carefully designed partnerships between the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Social Security offices, insurance exchanges, private health plans, and employers will be required to avoid interruptions in coverage over time.

Limitations

Several important limitations of this study should be noted. The use of self-reported medical conditions from MEPS may lead to some degree of undercounting, because undiagnosed health conditions will go unreported, and respondents do not always know or recall their conditions.41 Also, disability estimates are sensitive to question wordings in health surveys and the coding algorithms used to assess the data42; there is no single gold standard for disability measurement. Relative to the range of percentage estimates of working-aged persons with disabilities seen in the literature (13%43 and 16.5%34), the approach we take here results in a relatively conservative estimate of 13.9% reporting a disability. Third, the MEPS data do not provide any means by which to assess the clinical necessity or adequacy of services received. Lower utilization does not necessarily imply worse health outcomes.

Conclusions

The problem of being uninsured has never been limited to young, healthy adults who prefer to take their chances. We found that these coverage gaps spanned the entire working-aged population and included millions of persons with chronic conditions and disabilities that required ongoing care. The importance of uninterrupted insurance coverage for these population groups must not be underestimated. In addition, a secondary finding of this study is that some persons with chronic conditions and disabilities reported substantial levels of access problems and high out-of-pocket costs even when insured year-round. A key area for future research will be the content of benefit packages, both public and private, that arise in the new health care environment. In the end, it will be not only the promise of stable insurance over time but the actual value of the coverage available that will shape health care access, utilization, and financing for persons with chronic conditions and disabilities in the years to come.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health Clinical Research Center, Rehabilitation Medicine Department.

We thank Minh Huynh for his statistical consultation and three anonymous reviewers with the American Journal of Public Health for their comments on an earlier version of this article.

Human Participant Protection

The office of human subjects research of the National Institutes of Health determined that federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects do not apply to this work, because the data we used are in the public domain.

References

- 1.State Health Access Data Assistance Center At the Brink: Trends in America's Uninsured. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2009. Available at: http://covertheuninsured.org/files/u15/State_by_State_Analysis_2009.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Congressional Budget Office How Many People Lack Health Insurance and for How Long? Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office; 2003. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/42xx/doc4210/05-12-Uninsured.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein K, Glied S, Ferry D. Entrances and Exits: Health Insurance Churning, 1998–2000. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2005. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Content/Publications/Issue-Briefs/2005/Sep/Entrances-and-Exits–Health-Insurance-Churning–1998-2000.aspx. Accessed July 1, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Short PF, Graefe DR. Battery-powered health insurance? Stability in coverage of the uninsured. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22(6):244–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Short PF, Weaver FM. Transitioning to Medicare before age sixty-five. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):w175–w184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sommers BD. Loss of health insurance among non-elderly adults in Medicaid. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(1):1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanson KW, Neuman P, Dutwin D, Kasper JD. Uncovering the health challenges facing people with disabilities: the role of health insurance. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;suppl:w3-552–;w3–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer JA, Zeller PJ. Profiles of disability: employment and health coverage. Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 1999. Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/loader.cfm?url=/commonspot/security/getfile.cfm&PageID=13325. Accessed June 3, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reed MC, Tu HT. Triple jeopardy: low income, chronically ill and uninsured in America. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2002. Available at: http://www.hschange.com/CONTENT/411/411.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hafner-Eaton C. Physician utilization disparities between the uninsured and insured: comparisons of the chronically ill, acutely ill, and well nonelderly populations. JAMA. 1993;269(6):787–792 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrer RL. Pursuing equity: contact with primary care and specialist clinicians by demographics, insurance, and health status. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(6):492–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman C, Schwartz K. Eroding access among nonelderly US adults with chronic conditions: ten years of change. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(5):w340–w348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hadley J. Insurance coverage, medical care use, and short-term health changes following an unintentional injury or the onset of a chronic condition. JAMA. 2007;297(10):1073–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin J, Moon S. Quality of care and role of health insurance among non-elderly women with disabilities. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18(4):238–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry M, Dulio A, Hanson K. The role of health coverage for people with disabilities. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2003. Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/The-Role-of-Health-Coverage-for-People-with-Disabilities-Findings-from-12-Focus-Groups-with-People-with-Disabilities.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gulley SP, Altman BM. Disability in two health care systems: access, quality, satisfaction, and physician contacts among working-age Canadians and Americans with disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2008;1(4):196–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bodenheimer T, Berry-Millett R. Follow the money—controlling expenditures by improving care for patients needing costly services. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1521–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson GF, Knickman JR. Changing the chronic care system to meet people's needs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(6):146–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Machlin S, Cohen J, Beauregard K. Health care expenses for adults with chronic conditions, 2005. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Quality and Research; 2008. Available at: http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st203/stat203.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norris SL, High K, Gill TM, et al. Health care for older Americans with multiple chronic conditions: a research agenda. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(1):149–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson G, Horvath J. The growing burden of chronic disease in America. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(3):263–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson GF, Herbert R, Zeffiro T, Johnson N. Chronic conditions: making the case for ongoing care. Baltimore, MD: Partnership for Solutions; 2004. Available at: http://www.partnershipforsolutions.org/DMS/files/chronicbook2004.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care—a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1064–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jha A, Patrick DL, Maclehose RF, Doctor JN, Chan L. Dissatisfaction with medical services among Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(10):1335–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dejong G, Palsbo SE, Beatty PW, Jones GC, Knoll T, Neri MT. The organization and financing of health services for persons with disabilities. Milbank Q. 2002;80(2):261–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan L, Beaver S, Maclehose RF, Jha A, Maciejewski M, Doctor JN. Disability and health care costs in the Medicare population. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(9):1196–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hwang W, Weller W, Ireys H, Anderson GF. Out-of-pocket medical spending for care of chronic conditions. Health Aff. 2001;20(6):267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agency for Health Care Research and Quality Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Web site. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Research and Quality; 2009. Available at: http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb. Accessed June 5, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agency for Health Care Research and Quality Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component statistical estimation issues. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Research and Quality; 2009. Available at: http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/about_meps/workbook/WB-Weight_Estimat.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein RE, Westbrook LE, Bauman LJ. The questionnaire for identifying children with chronic conditions: a measure based on a noncategorical approach. Pediatrics. 1997;99(4):513–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banthin JS, Bernard DM. Changes in financial burdens for health care: national estimates for the population younger than 65 years, 1996 to 2003. JAMA. 2006;296(22):2712–2719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc B. 1995;57(1):289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tu HT, Cohen GR. Financial and health burdens of chronic conditions grow. Tracking report 24 Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2009. Available at: http://www.hschange.com/CONTENT/1049/#ib8. Accessed April 21, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brault MW. Americans with disabilities: 2005. Current Population Reports P70-117 Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2008. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2008pubs/p70-117.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson GF. Physician, public, and policymaker perspectives on chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(4):437–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rimmer JH. Health promotion for people with disabilities: the emerging paradigm shift from disability prevention to prevention of secondary conditions. Phys Ther. 1999;79(5):495–502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan L, Doctor JN, MacLehose RF, et al. Do Medicare patients with disabilities receive preventive services? A population-based study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(6):642–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stroupe KT, Kinney ED, Kniesner TJ. Chronic illness and health insurance-related job lock. Working Paper 19 Syracuse, NY: Center for Policy Research, Syracuse University; 2000. Available at: http://www-cpr.maxwell.syr.edu/cprwps/pdf/wp19.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stapleton D, Liu S. Will health care reform increase the employment of people with disabilities? Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research; 2009. Available at: http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/publications/pdfs/disability/healthcarereform.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neuhauser L, Rothschild B, Graham C, Ivey SL, Konishi S. Participatory design of mass health communication in three languages for seniors and people with disabilities on Medicaid. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(12):2188–2194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Machlin S, Cohen J, Beauregard K, Steiner C. Sensitivity of household reported medical conditions in the medical expenditure panel survey. Med Care. 2009;47(6):618–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Altman BM, Gulley SP. Convergence and divergence: differences in disability prevalence estimates in the United States and Canada based on four health survey instruments. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(4):543–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.US Census Bureau American Community Survey. Percent of people 21 to 64 years old with a disability: 2006. Table R1802, generated using American FactFinder. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov. Accessed April 21, 2010