Abstract

Group G Streptococcus has been implicated as a causative agent of pharyngitis in outbreak situations, but its role in endemic disease remains elusive. We found an unexpected inverse association of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis colonization and sore throat in a study of 2,194 children of 3 to 15 years of age in Salvador, Brazil.

The role of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis as a causative agent of endemic pharyngitis has been debated for more than 50 years (4, 8, 14, 19, 26, 28, 29, 37). S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis has been implicated as a causative agent of pharyngitis in outbreak situations, but its role in endemic disease remains elusive (6, 12, 16, 20, 24, 27, 35). Nomenclature changes among non-group A beta-hemolytic streptococci (non-GAS) have contributed to the difficulty of establishing disease association (13, 25). Advances in techniques for identication of microorganisms to the species level have revealed streptococci with carbohydrate groups C and G (GCS and GGS) to be comprised of several streptococcal species, where some species can express either group C or G carbohydrate antigen.

The most common human beta-hemolytic GGS and GCS include S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and Streptococcus anginosus. GGS/GCS are most commonly considered commensals with the capacity to cause opportunistic infections in individuals with underlying medical conditions (1, 31). However, in recent decades, GGS/GCS have increasingly been implicated in diseases that occur in healthy individuals (3, 30). GGS/GCS and GAS inhabit the same tissue sites, and the disease spectrum caused by GGS/GCS overlaps that of GAS (1, 2, 7, 15, 17, 18, 21). Virulence factor genes are transferred between GAS and GGS/GCS via mobile genetic elements such as transposons and phages (5, 9-11, 22, 23, 32, 33, 36).

In highly crowded settings, GAS, GGS, and GCS may undergo frequent person-to-person transmission. We examined GGS/GCS isolates from throats of children in slum and nonslum communities in Salvador, Brazil, and compared their possible association with sore throat.

Patients aged 3 to 15 years were recruited consecutively from pediatric outpatient emergency clinics A, B, and C from 17 April 2008 to 31 October 2008. Clinical services at clinics A and B are offered free to patients through the publicly funded Unified Health System (SUS); most of the patients are residents of slum communities. Clinic C serves only those with private health insurance. Following consent procedures, a standardized questionnaire and throat swab sample were conducted with each study participant. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from all participating institutions.

Cases were defined as children whose chief complaint was sore throat. Culture-confirmed sore throat was defined as sore throat in a child with GAS or GGS/GCS isolated from the throat swab. Controls were defined as children visiting the clinics for reasons other than sore throat. Children who used antibiotics in the previous 2 weeks or required hospitalization on the day of recruitment were excluded. Patient-related variables recorded by the standardized questionnaire are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bivariable analysis of risk factors for sore throat in a pediatric outpatient population in Salvador, Brazil

| Covariate | Value for groupa |

OR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with sore throat (n = 624) | Patients without sore throat (n = 1,557) | ||||

| No. (%) of males | 285 (45.7) | 843 (54.1) | 0.71 | 0.59-0.86 | <0.001 |

| No. (%) of slum dwellers | 337 (54.0) | 929 (59.7) | 0.79 | 0.66-0.96 | 0.015 |

| No. (%) of patients in age group (yr) | |||||

| 3-5 | 226 (36.2) | 511 (32.8) | 1.0 | ||

| 6-8 | 165 (26.4) | 481 (30.9) | 0.78 | 0.61-0.98 | 0.03 |

| 9-11 | 148 (23.7) | 365 (23.4) | 0.92 | 0.72-1.17 | 0.49 |

| 12-15 | 85 (13.6) | 200 (12.8) | 0.96 | 0.71-1.29 | 0.79 |

| No. (%) of patients with indicated monthly salary (reais) | |||||

| ≤415 | 189 (32.3) | 494 (33.5) | 1.0 | ||

| 416-830 | 129 (22.0) | 414 (28.1) | 0.81 | 0.63-1.06 | 0.12 |

| 831-1,660 | 92 (15.7) | 241 (16.3) | 1.00 | 0.74-1.34 | 0.99 |

| 1,661-2,490 | 60 (10.2) | 134 (9.1) | 1.17 | 0.83-1.66 | 0.38 |

| ≥2,491 | 116 (19.8) | 193 (13.1) | 1.57 | 1.18-2.09 | 0.002 |

| Mean (SD) no. of people/house | 4.31 (0.07) | 4.26 (0.04) | 4.18-4.34 | 0.53 | |

| Mean (SD) no. of people aged ≤15 yr/house | 1.86 (0.04) | 1.83 (0.03) | 4.18-4.44 | 0.67 | |

| No. (%) of patients with indicated mother's education | |||||

| Primary, incomplete | 159 (25.8) | 425 (27.7) | 1.0 | ||

| Primary, complete | 37 (6.0) | 125 (8.2) | 0.79 | 0.53-1.19 | 0.26 |

| Secondary, incomplete | 44 (7.1) | 151 (9.8) | 0.78 | 0.53-1.14 | 0.20 |

| Secondary, complete | 241 (39.1) | 573 (37.4) | 1.12 | 0.89-1.42 | 0.33 |

| University or beyond | 133 (21.6) | 247 (16.1) | 1.44 | 1.09-1.90 | 0.01 |

| Illiterate | 3 (0.49) | 13 (0.85) | 0.62 | 0.17-2.19 | 0.46 |

| No. (%) of patients with indicated father's education | |||||

| Primary, incomplete | 124 (22.4) | 345 (25.0) | 1.0 | ||

| Primary, complete | 45 (8.1) | 122 (8.8) | 1.03 | 0.69-1.53 | 0.90 |

| Secondary, incomplete | 33 (6.0) | 113 (8.2) | 0.81 | 0.52-1.26 | 0.35 |

| Secondary, complete | 220 (39.7) | 585 (42.4) | 1.05 | 0.81-1.35 | 0.73 |

| University or beyond | 126 (22.7) | 207 (15.0) | 1.69 | 1.25-2.29 | 0.001 |

| Illiterate | 6 (1.1) | 9 (0.7) | 1.85 | 0.65-5.32 | 0.25 |

| No. (%) of patients in school | 552 (88.6) | 1394 (89.5) | 0.91 | 0.67-1.24 | 0.53 |

| No. (%) of patients in day care | 40 (6.4) | 75 (4.8) | 1.36 | 0.89-2.04 | 0.13 |

| No. (%) of patients with streptococcal colonization | |||||

| Group G (all species) | 25 (4.0) | 108 (6.9) | 0.56 | 0.34-0.88 | 0.01 |

| Group C (all species) | 14 (2.2) | 43 (2.8) | 0.81 | 0.41-1.52 | 0.49 |

| S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis | 12 (1.9) | 59 (3.8) | 0.50 | 0.24-0.94 | 0.03 |

| S. anginosus | 17 (2.7) | 69 (4.4) | 0.60 | 0.33-1.05 | 0.06 |

| Group A Streptococcus | 128 (20.5) | 124 (8.0) | 2.98 | 2.26-3.93 | <0.001 |

The data for 13 subjects were missing case/control status.

A sterile cotton swab tip was applied to the posterior pharynx and tonsils of each participant. Swabs were placed immediately in Stuart transport medium, transported to the laboratory, and plated the same day of collection on 5% sheep blood agar. Plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 to 48 h. Streptococci were identified phenotypically by beta-hemolysis, colony morphology, and the catalase test. Carbohydrate group identification was performed by positive latex agglutination (Remel PathoDx Strep Grouping latex test kit; Remel, Lenexa, KS). DNA isolation was performed with a DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

PCR amplifications were carried out in a total volume of 25 μl containing 2 μl of template DNA, 0.5 μl of 50 μM (each) forward (16S-8F [5′-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG-3′]) and reverse (16S-806R [5′-GGA CTA CCA GGG TAT CTA ATC C-3′]) primers, 2.5 μl of 10× buffer, 15 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μl of 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mix, and 0.1 μl of 5,000-U/ml Taq polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA).

Analyses were conducted with STATA 11.0 (Stata Inc., College Station, TX). Categorical variables were compared between cases and controls by the chi-square test or two-tailed Fisher's exact test. Student's t test was used to compare means. Selection of variables for the multivariable model was done by backward stepwise logistic regression with a cutoff P value of 0.20. The multivariable model was used to evaluate the association between the presence of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. anginosus and case status while controlling for the covariates age, sex, slum versus nonslum, and culture-positive GAS status. We evaluated effect modification between covariates by the Mantel-Haenszel test of homogeneity following bivariable stratification with cross-product terms in the multivariable model. Evaluation of interactions was done with females with no S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis infection and no GAS infection as the reference group.

During the study period, 2,194 eligible children aged 3 to 15 years (759 in clinic A, 518 in clinic B, and 917 in clinic C) were enrolled in the study. Of 2,181 children with data on case status, 624 (28.6%) reported sore throat (cases), and 1,557 (71.4%) presented with other illnesses. Reasons for hospital visit among the controls were comparable across all three clinics (data not shown).

In total, 133 (6.1%) GGS isolates and 57 (2.6%) GCS isolates were obtained from 2,194 children. Of 133 GGS isolates, 122 were identified to the species level; 59 were S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, 61 were S. anginosus, and 1 was S. constellatus. Of 57 GCS isolates, 39 were identified to the species level; 12 were S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, 26 were S. anginosus, and 1 was S. constellatus.

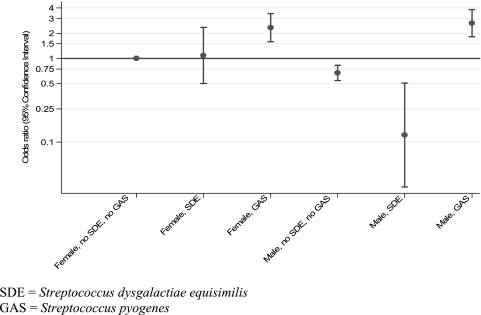

Income of more than six times the minimum wage, university education of the mother and father, age of 3 to 5 years old, and isolation of GAS were each associated with sore throat in bivariable analyses. However, unexpectedly, slum residence, being male, and colonization with GGS, specifically with S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, were inversely associated with sore throat. In multivariable analyses adjusted for presence of GAS, presence of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, sex, and interaction terms for sex, GAS, and S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, living in a slum was associated with reduced odds of sore throat (odds ratio [OR] = 0.79; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.65 to 0.96; P = 0.018); an age of 3 to 5 years was associated with increased odds of sore throat compared with that for children aged 6 to 8 years (P = 0.011). S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis colonization in slum-dwelling male children only was inversely associated with sore throat (OR = 0.12; CI, 0.03 to 0.51; P = 0.004) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Effect of sex on the association of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and S. pyogenes with sore throat in children aged 3 to 15 years in Salvador, Brazil.

To our knowledge, an inverse association between colonization with S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and sore throat has not been reported previously. This study, conducted in an endemic setting, and the identification of GGS/GCS to the species level may have enabled us to identify this previously unrecognized association. Whereas S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis is morphologically similar to GAS and shares structural features such as the M protein, S. anginosus is morphologically distinct. The hypervariable terminal region of the M protein is known to be immunogenic. It is possible that S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis colonization induces a cross-protective mucosal immune response against subsequent GAS colonization or infection or that S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and GAS exhibit competitive colonization in the throat.

The inverse association was strongest for male children living in a slum. It is possible that slum children experience repeated exposures to causative agents early in life and may develop immunity earlier against symptomatic infections. The fact that the association between GGS and sore throat differs by sex has been detected in previous studies (34). Further studies may elucidate the biological plausibility of this gender difference.

Further studies of the epidemiology of GGS stratified by species are needed, particularly in high-density urban settings where the prevalence of these bacteria appears to be high and where environmental and socioeconomic conditions favor high rates of transmission.

Acknowledgments

This report was funded by a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grant for public health dissertation research (R36).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baracco, G. J., and A. L. Bisno. 2006. Group C and group G streptococcal infections: epidemiologic and clinical aspects, p. 222-229. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferreti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 2.Brandt, C. M., and B. Spellerberg. 2009. Human infections due to Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:766-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broyles, L. N., C. Van Beneden, B. Beall, R. Facklam, P. L. Shewmaker, P. Malpiedi, P. Daily, A. Reingold, and M. M. Farley. 2009. Population-based study of invasive disease due to beta-hemolytic streptococci of groups other than A and B. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:706-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cimolai, N., R. W. Elford, L. Bryan, C. Anand, and P. Berger. 1988. Do the beta-hemolytic non-group A streptococci cause pharyngitis? Rev. Infect. Dis. 10:587-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleary, P. P., J. Peterson, C. Chen, and C. Nelson. 1991. Virulent human strains of group G streptococci express a C5a peptidase enzyme similar to that produced by group A streptococci. Infect. Immun. 59:2305-2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen, D., M. Ferne, T. Rouach, and S. Bergner-Rabinowitz. 1987. Food-borne outbreak of group G streptococcal sore throat in an Israeli military base. Epidemiol. Infect. 99:249-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen-Poradosu, R., J. Jaffe, D. Lavi, S. Grisariu-Greenzaid, R. Nir-Paz, L. Valinsky, M. Dan-Goor, C. Block, B. Beall, and A. E. Moses. 2004. Group G streptococcal bacteremia in Jerusalem. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1455-1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornfeld, D., and J. P. Hubbard. 1961. A four-year study of the occurrence of beta-hemolytic streptococci in 64 school children. N. Engl. J. Med. 264:211-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies, M. R., D. J. McMillan, G. H. Van Domselaar, M. K. Jones, and K. S. Sriprakash. 2007. Phage 3396 from a Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis pathovar may have its origins in Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Bacteriol. 189:2646-2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies, M. R., J. Shera, G. H. Van Domselaar, K. S. Sriprakash, and D. J. McMillan. 2009. A novel integrative conjugative element mediates genetic transfer from group G streptococcus to other beta-hemolytic streptococci. J. Bacteriol. 191:2257-2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies, M. R., T. N. Tran, D. J. McMillan, D. L. Gardiner, B. J. Currie, and K. S. Sriprakash. 2005. Inter-species genetic movement may blur the epidemiology of streptococcal diseases in endemic regions. Microbes Infect. 7:1128-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Efstratiou, A. 1989. Outbreaks of human infection caused by pyogenic streptococci of Lancefield groups C and G. J. Med. Microbiol. 29:207-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Facklam, R. 2002. What happened to the streptococci: overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:613-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox, K., J. Turner, and A. Fox. 1993. Role of beta-hemolytic group C streptococci in pharyngitis: incidence and biochemical characteristics of Streptococcus equisimilis and Streptococcus anginosus in patients and healthy controls. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:804-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaunt, P. N., and D. V. Seal. 1987. Group G streptococcal infections. J. Infect. 15:5-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerber, M. A., M. F. Randolph, N. J. Martin, M. F. Rizkallah, P. P. Cleary, E. L. Kaplan, and E. M. Ayoub. 1991. Community-wide outbreak of group G streptococcal pharyngitis. Pediatrics 87:598-603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haidan, A., S. R. Talay, M. Rohde, K. S. Sriprakash, B. J. Currie, and G. S. Chhatwal. 2000. Pharyngeal carriage of group C and group G streptococci and acute rheumatic fever in an Aboriginal population. Lancet 356:1167-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashikawa, S., Y. Iinuma, M. Furushita, T. Ohkura, T. Nada, K. Torii, T. Hasegawa, and M. Ohta. 2004. Characterization of group C and G streptococcal strains that cause streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:186-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayden, G. F., T. F. Murphy, and J. O. Hendley. 1989. Non-group A streptococci in the pharynx. Pathogens or innocent bystanders? Am. J. Dis. Child. 143:794-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill, H. R., G. G. Caldwell, E. Wilson, D. Hager, and R. A. Zimmerman. 1969. Epidemic of pharyngitis due to streptococci of Lancefield group G. Lancet ii:371-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson, C., and A. Tunkel. 2000. Viridans streptococci and groups C and G streptococci, p. 2167-2182. In J. B. G. Mandell and R. Dolin (ed.), Principles and practice of infectious diseases. Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, PA.

- 22.Kalia, A., and D. E. Bessen. 2003. Presence of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A and C genes in human isolates of group G streptococci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 219:291-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalia, A., M. C. Enright, B. G. Spratt, and D. E. Bessen. 2001. Directional gene movement from human-pathogenic to commensal-like streptococci. Infect. Immun. 69:4858-4869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24.Kaplan, E., M. Nussbaum, I. R. Shenker, M. Munday, and H. D. Isenberg. 1977. Group C hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis. J. Pediatr. 90:327-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lancefield, R. C. 1933. A serological differentiation of human and other groups of hemolytic streptococci. J. Exp. Med. 57:571-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindbaek, M., E. A. Hoiby, G. Lermark, I. M. Steinsholt, and P. Hjortdahl. 2005. Clinical symptoms and signs in sore throat patients with large colony variant beta-haemolytic streptococci groups C or G versus group A. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 55:615-619. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCue, J. D. 1982. Group G streptococcal pharyngitis. Analysis of an outbreak at a college. JAMA 248:1333-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMillan, J. A., C. Sandstrom, L. B. Weiner, B. A. Forbes, M. Woods, T. Howard, L. Poe, K. Keller, R. M. Corwin, and J. W. Winkelman. 1986. Viral and bacterial organisms associated with acute pharyngitis in a school-aged population. J. Pediatr. 109:747-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meier, F. A., R. M. Centor, L. Graham, Jr., and H. P. Dalton. 1990. Clinical and microbiological evidence for endemic pharyngitis among adults due to group C streptococci. Arch. Intern. Med. 150:825-829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinho, M. D., J. Melo-Cristino, and M. Ramirez. 2006. Clonal relationships between invasive and noninvasive Lancefield group C and G streptococci and emm-specific differences in invasiveness. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:841-846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruoff, K. L. 1988. Streptococcus anginosus (“Streptococcus milleri”): the unrecognized pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1:102-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson, W. J., J. M. Musser, and P. P. Cleary. 1992. Evidence consistent with horizontal transfer of the gene (emm12) encoding serotype M12 protein between group A and group G pathogenic streptococci. Infect. Immun. 60:1890-1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sriprakash, K. S., and J. Hartas. 1996. Lateral genetic transfers between group A and G streptococci for M-like genes are ongoing. Microb. Pathog. 20:275-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steer, A. C., A. W. Jenney, J. Kado, M. F. Good, M. Batzloff, G. Magor, R. Ritika, K. E. Mulholland, and J. R. Carapetis. 2009. Prospective surveillance of streptococcal sore throat in a tropical country. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 28:477-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stryker, W. S., D. W. Fraser, and R. R. Facklam. 1982. Foodborne outbreak of group G streptococcal pharyngitis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 116:533-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Towers, R. J., D. Gal, D. McMillan, K. S. Sriprakash, B. J. Currie, M. J. Walker, G. S. Chhatwal, and P. K. Fagan. 2004. Fibronectin-binding protein gene recombination and horizontal transfer between group A and G streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5357-5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner, J. C., F. G. Hayden, M. C. Lobo, C. E. Ramirez, and D. Murren. 1997. Epidemiologic evidence for Lancefield group C beta-hemolytic streptococci as a cause of exudative pharyngitis in college students. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]