Abstract

We report a case of acute Plasmodium malariae infection complicating corticosteroid treatment for membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in a patient from an area where P. malariae infection is not endemic. A peripheral blood smear showed typical band-form trophozoites compatible with P. malariae or Plasmodium knowlesi. SSU rRNA sequencing confirmed the identity to be P. malariae.

CASE REPORT

A 72-year-old man with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, hypertension, and α-thalassemia trait was admitted to our hospital because of chills and rigor for 2 days and a fever on the day of admission. He had been diagnosed with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis 3 years prior to admission, when he presented with nephrotic syndrome. Autoimmune marker testing showed a raised level of antinuclear antibody (>1/720), with a normal level of anti-double-stranded-DNA antibody (<5 IU/ml) and a negative result for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA). Testing for hepatitis B virus surface antigen showed a negative result. His initial renal biopsy specimen at diagnosis showed immune deposits of IgA, IgG, IgM, C3, and C1q. He was treated with high-dose corticosteroid with partial response. Two months prior to admission, he had recurrent lower limb edema and was confirmed to have a relapse of the nephrotic syndrome, with urine protein excretion of 2.78 g/day. Prednisolone at 50 mg once daily was started 50 days before admission, with a gradual tailing dose. On the day of admission, his prednisolone dosage was 35 mg once daily. The patient was a resident of Hong Kong. He occasionally traveled to southern China, but he has never traveled outside this area in his lifetime. He has never received a blood transfusion.

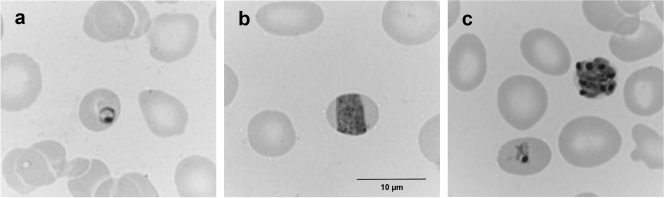

On admission, he had a temperature of 39.3°C and a heart rate of 138 beats per minute. His blood pressure was 144/68 mm Hg. Physical examination revealed bilateral lower limb edema. The spleen was not palpable. A blood test showed thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of 69 × 109/liter. The platelet count 6 weeks before admission was within the normal range (253 × 109/liter). The total white cell count was 4.4 × 109/liter, with a neutrophil count of 4.09 × 109/liter and a lymphocyte count of 0.26 × 109/liter. The hemoglobin level was 7.4 g/dl. Biochemical tests revealed a creatinine level of 2.68 mg/dl and an albumin level of 31 g/liter. The levels for bilirubin and liver parenchymal enzymes were within the normal range. A peripheral blood smear showed normal-sized erythrocytes, thick rings (Fig. 1a), band-form trophozoites (Fig. 1b), and schizonts containing dark brown pigments (Fig. 1c), compatible with Plasmodium malariae or P. knowlesi. The level of parasitemia was 0.1%. There was no growth in one set of blood culture after 5 days of incubation. Urine culture was not performed, in view of normal urinalysis except proteinuria. The nasopharyngeal aspirate was negative for influenza viruses A and B, for parainfluenza virus types 1, 2, and 3, for adenovirus, and for respiratory syncytial virus by direct immunofluorescence (19) and for pandemic (H1N1) influenza virus by reverse transcriptase PCR (16). A chest radiograph showed left apical pleural thickening, but lung fields were clear. Oral chloroquine (600 mg, then 300 mg once 6 h later, and then 300 mg once daily for 2 days) was started on the second day of admission. Intravenous ceftriaxone at 1 g once daily was also given in view of possible bacterial coinfection. His condition gradually improved, his platelet count returned to 155 × 109/liter on day 9 of hospitalization, and he was discharged on the same day. Urine protein excretion was reduced to 0.57 g/day 19 days after admission. He remained asymptomatic at the time of writing, 6 months after discharge.

FIG. 1.

Peripheral blood smear of our patient, taken on the day of admission. (a) Thick ring; (b) band-form trophozoite, typical of P. malariae or P. knowlesi; (c) schizonts containing dark brown pigments.

SSU rRNA sequencing.

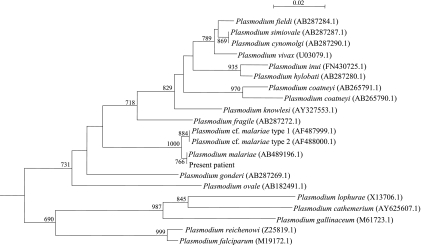

DNA extraction, nested PCR amplification, and DNA sequencing of the small-subunit (SSU) rRNA gene of the Plasmodium species from our patient were performed according to a previous publication (12, 13), using LPW12271 (5′-TCAAAGATTAAGCCATGCAAGTGA-3′) and LPW12272 (5′-CCTGTTGTTGCCTTAAACTCC-3′) for the primary PCR amplification and LPW12273 (5′-TTTTTATAAGGATAACTACGGAAAAGCTGT-3′) and LPW12274 (5′-TACCCGTCATAGCCATGTTAGGCCAATACC-3′) (Sigma-Proligo, Singapore) for the nested PCR amplification and DNA sequencing. The sequences of the PCR products were compared with sequences of closely related Plasmodium species in GenBank by multiple sequence alignment using ClustalX 1.83 (15). Phylogenetic relationships were determined using the neighbor-joining method. Sequencing of the SSU rRNA gene of the Plasmodium species from our patient showed that there were 0- to 2-base (0 to 1%) differences between the SSU rRNA gene sequence of the Plasmodium species from our patient and those of P. malariae (GenBank accession no. AB489196.1, AF487999.1, and AF488000.1) but >19-base (9%) differences between the SSU rRNA gene sequence of the Plasmodium species from our patient and those of other Plasmodium species, indicating that the Plasmodium species from our patient was P. malariae (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships of the patient's Plasmodium species to other, closely related Plasmodium species. The tree was inferred from SSU rRNA data by the neighbor-joining method using Kimura's two-parameter correction and was rooted using Cryptosporidium baileyi (EU814425.1). Two hundred one nucleotide positions were included in the analysis. The scale bar indicates the estimated number of substitutions per 50 bases. All names and accession numbers are given as cited in the GenBank database.

Traditionally, human malaria can be caused by one of four Plasmodium species, Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae. Recently, a simian Plasmodium species, P. knowlesi, was described to be a cause of severe acute human infection resembling P. falciparum infection (3, 13). Morphologically, P. knowlesi is indistinguishable from P. malariae, and these two species can be distinguished only by molecular technologies, such as SSU rRNA sequencing. Among these five Plasmodium species, P. malariae is considered to be the most benign species causing malaria in terms of acute illness (18). Severe and acute presentations of P. malariae infections have rarely been reported in the literature (Table 1). In this article, we describe a case of SSU rRNA sequencing-confirmed acute Plasmodium malariae infection complicating corticosteroid treatment.

TABLE 1.

Severe cases of Plasmodium malariae infections reported in the literaturea

| Reference or source | Age (yr) | Sex | Underlying disease(s) | No. of platelets (109)/liter | Complication(s) | Treatment | Confirmation of P. malariae by PCR sequencing (target gene) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 28 | M | None | 30 | ARDS, acute renal failure, shock, lactic acidosis, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy | Intravenous quinine | Yes (SSU rRNA gene) |

| 10 | 32 | M | None | 93 | Generalized convulsion | Intravenous quinine | Yes (18S rRNA gene) |

| 14 | 42 | F | Metastatic carcinoma of the colon, splenectomy | Not available | Confusion | Oral chloroquine | Not performed |

| Present case | 72 | M | Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, hypertension, alpha thalassemia trait | 69 | Sepsis, thrombocytopenia | Oral chloroquine | Yes (SSU rRNA gene) |

M, male; F, female; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Our patient might have contracted the initial P. malariae infection many years ago, causing the membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, with exacerbation of the acute P. malariae disease due to corticosteroid therapy; or alternatively, he might have acquired the parasite recently and had a severe acute infection due to corticosteroid therapy. For both scenarios, the patient would most likely have acquired the infection in southern China, an area where malaria is still prevalent, due to frequent travel (23). P. malariae is well known to cause chronic malarial nephropathy (4), but acute renal failure has also been reported (9). P. malariae infection usually leads to immune complex-mediated glomerular disease, resulting in nephrotic syndrome. Although it is highly likely that the patient would have acquired the malaria which led to membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, P. malariae infection was not seen on a blood film previously. One possibility is that P. malariae usually exhibits low-level parasitemia (2). P. malariae infections are often diagnosed after corticosteroid therapy in the treatment for glomerulonephritis (9), and it is possible that corticosteroid suppresses the host immunity and allows the proliferation of P. malariae. The effect of steroid on Plasmodium infections has been studied in animal models, with contradictory results. In a mouse model infected with Plasmodium yoelii, the dexamethasone group had higher numbers of rings, trophozoites, and schizonts than the control group (11). However, in another study, using squirrel monkeys, dexamethasone was shown to suppress P. falciparum in a dose-dependent manner (7). Plasmodium infections are frequently missed, especially in patients who have not traveled to areas of endemicity. However, P. malariae may manifest in patients in areas where P. malariae infection is not endemic, because of recrudescence (1, 17) or importation via animal species (6). The acute illness with thrombocytopenia in our patient may be confused with severe bacterial sepsis. However, there was no evidence of other infections from microbiological investigations of blood, sputum, urine, and nasopharyngeal aspirate samples. The acute onset and prompt recovery of thrombocytopenia suggests that the low platelet count was related to the severe infection (8).

SSU rRNA sequencing is a useful tool for accurate identification of Plasmodium species. Only three cases of severe acute infections due to P. malariae have been reported (Table 1). The first case was that of a 28-year-old immunocompetent man who presented with a fever and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome 5 weeks after returning to France from Côte d'Ivoire (5), whereas the other two cases were cerebral malaria in a 32-year-old man from Bangladesh (10) and a 42-year-old woman who had metastatic carcinoma of the colon and a history of splenectomy (14). It has been found that Plasmodium species, even those that are theoretically distinguishable by morphology, are frequently misidentified, even in areas of endemicity where the blood films are examined by experienced microscopists (3). For our patient, we were unable to distinguish between P. malariae and P. knowlesi by blood film examination. Since P. malariae is rarely associated with acute sepsis, and septic workup did not reveal any coinfection, P. knowlesi was initially suspected and SSU rRNA sequencing was performed to confirm the identification of the Plasmodium isolate to the species level, which unexpectedly turned out to be a case of P. malariae. In fact, one of the three reported cases of severe P. malariae infections was confirmed by SSU rRNA sequencing (5). Similar to what was found for bacterial and fungal infections (20-22), a polyphasic approach using a combination of phenotypic identification and rRNA sequencing is required for identification and novel species discovery in parasitic infections in the long run.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The SSU rRNA gene sequence of the Plasmodium species has been lodged within the GenBank sequence database under accession number GU950655.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the University Development Fund and the Committee for Research and Conference Grant, The University of Hong Kong.

We thank Gavin S. W. Chan and K. W. Chan for reviewing the renal biopsy specimen.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 August 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chim, C. S., S. S. Wong, C. C. Lam, and K. W. Chan. 2004. Concurrent hyperreactive malarial splenomegaly and quartan malarial nephropathy—Plasmodium malariae revisited. Haematologica 89:ECR21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins, W. E., and G. M. Jeffery. 2007. Plasmodium malariae: parasite and disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20:579-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox-Singh, J., T. M. Davis, K. S. Lee, S. S. Shamsul, A. Matusop, S. Ratnam, H. A. Rahman, D. J. Conway, and B. Singh. 2008. Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in humans is widely distributed and potentially life threatening. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:165-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das, B. S. 2008. Renal failure in malaria. J. Vector Borne Dis. 45:83-97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Descheemaeker, P. N., J. P. Mira, F. Bruneel, S. Houzé, M. Tanguy, J. P. Gangneux, E. Flecher, C. Rousseau, J. Le Bras, and Y. Mallédant. 2009. Near-fatal multiple organ dysfunction syndrome induced by Plasmodium malariae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:832-834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayakawa, T., N. Arisue, T. Udono, H. Hirai, J. Sattabongkot, T. Toyama, T. Tsuboi, T. Horii, and K. Tanabe. 2009. Identification of Plasmodium malariae, a human malaria parasite, in imported chimpanzees. PLoS One 4:e7412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katakai, Y., S. Suzuki, Y. Tanioka, S. Hattori, Y. Matsumoto, M. Aikawa, and M. Ito. 2002. The suppressive effect of dexamethasone on the proliferation of Plasmodium falciparum in squirrel monkeys. Parasitol. Res. 88:53-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mavrommatis, A. C., T. Theodoridis, A. Orfanidou, C. Roussos, V. Christopoulou-Kokkinou, and S. Zakynthinos. 2000. Coagulation system and platelets are fully activated in uncomplicated sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 28:451-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neri, S., D. Pulvirenti, I. Patamia, A. Zoccolo, and P. Castellino. 2008. Acute renal failure in Plasmodium malariae infection. Neth. J. Med. 66:166-168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman, W., K. Chotivanich, K. Silamut, N. Tanomsing, A. Hossain, M. A. Faiz, A. M. Dondorp, and R. J. Maude. 2010. Plasmodium malariae in Bangladesh. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 104:78-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rungruang, T., and S. K. Klosek. 2007. Chronic steroid administration does not suppress Plasmodium development and maturation. Parasitol. Res. 101:1091-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh, B., A. Bobogare, J. Cox-Singh, G. Snounou, M. S. Abdullah, and H. A. Rahman. 1999. A genus- and species-specific nested polymerase chain reaction malaria detection assay for epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 60:687-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh, B., L. Kim Sung, A. Matusop, A. Radhakrishnan, S. S. Shamsul, J. Cox-Singh, A. Thomas, and D. J. Conway. 2004. A large focus of naturally acquired Plasmodium knowlesi infections in human beings. Lancet 363:1017-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tapper, M. L., and D. Armstrong. 1976. Malaria complicating neoplastic disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 136:807-810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.To, K. K., K. H. Chan, I. W. Li, T. Y. Tsang, H. Tse, J. F. Chan, I. F. Hung, S. T. Lai, C. W. Leung, Y. W. Kwan, Y. L. Lau, T. K. Ng, V. C. Cheng, J. S. Peiris, and K. Y. Yuen. 2010. Viral load in patients infected with pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza A virus. J. Med. Virol. 82:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vinetz, J. M., J. Li, T. F. McCutchan, and D. C. Kaslow. 1998. Plasmodium malariae infection in an asymptomatic 74-year-old Greek woman with splenomegaly. N. Engl. J. Med. 338:367-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White, N. J. 2009. Malaria, p. 1201-1301. In C. G. Cook and A. I. Zumla (ed.), Manson's tropical diseases, 22nd ed. W. B. Saunders, London, United Kingdom.

- 19.Woo, P. C., S. S. Chiu, W. H. Seto, and M. Peiris. 1997. Cost-effectiveness of rapid diagnosis of viral respiratory tract infections in pediatric patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1579-1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woo, P. C., S. K. Lau, A. H. Ngan, H. Tse, E. T. Tung, and K. Y. Yuen. 2008. Lasiodiplodia theobromae pneumonia in a liver transplant recipient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:380-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woo, P. C., S. K. Lau, A. H. Ngan, E. T. Tung, S. Y. Leung, K. K. To, V. C. Cheng, and K. Y. Yuen. 2010. Lichtheimia hongkongensis sp. nov., a novel Lichtheimia spp. associated with rhinocerebral, gastrointestinal and cutaneous mucormycosis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 66:274-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woo, P. C., S. K. Lau, J. L. Teng, H. Tse, and K. Y. Yuen. 2008. Then and now: use of 16S rDNA gene sequencing for bacterial identification and discovery of novel bacteria in clinical microbiology laboratories. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14:908-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou, S. S., Y. Wang, W. Fang, and L. H. Tang. 2009. Malaria situation in the People's Republic of China in 2008. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi 27:455-457. (In Chinese and English.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]