Abstract

Various innate-like T cell subsets preferentially reside in specific epithelial tissues as the first line of defence. However, mechanisms regulating their tissue-specific development are poorly understood. Using the prototypical skin intraepithelial γδT cells (sIEL) as a model, we herein show that a TCR-mediated selection plays an important role in promoting acquisition of a specific skin-homing property by fetal thymic sIEL precursors for their epidermal location and the skin-homing potential is intrinsically programmed even before the selection. In addition, once localized in the skin, the sIEL precursors develop into sIELs without the requirement of further TCR/ligand interaction. These studies reveal that development of the tissue-specific lymphocytes is a “hard-wired” process that targets them to specific tissues for proper functions.

Introduction

Besides conventional αβT cells that reside in secondary lymphoid organs (SLO) for adaptive responses, various unconventional T cell subsets, such as γδT cells with innate properties, preferentially reside in epithelial tissues as the first line of defense. However, their tissue-specific development processes are poorly understood.

Recent studies suggest that development of the tissue-resident T cells is determined intrathymically. We found that fetal thymic precursors for skin-specific sIELs (also called dendritic epidermal T cells or DETC) express a unique pattern of migration molecules, such as chemokine receptor CCR10 that plays a role in their homing to the epidermis (1, 2). Similarly, subsets of adult thymic αβ and γδ T cells were found to display homing properties associated with their intestinal location (3)(4).

A TCR-mediated thymic selection is likely involved in the acquisition of unique homing properties by the specific T cells subsets (1, 4). Fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors deficient of a TCR signalling molecule Itk could not acquire the skin-homing property properly (5). In addition, Vγ3+ sIEL precursors remain at an immature status and could not develop into sIELs in a strain of FVB mice (Tac) that bear mutated Skint1, a selecting molecule for the Vγ3+ sIEL precursors (6). However, how the different thymic T cell subsets acquire unique homing properties are unknown. We show herein that the development of tissue-specific T cells is an intrinsically programmed process.

Materials And Methods

Mice

KN6 and G8 γδTCR transgenic (Tg) mice were described (7, 8). Balb/c, C57BL/6 (B6), TCRδ−/−, and β2M−/− mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory; FVB(NCI) from National Cancer Institute; FVB(Tac) from Taconic. KN6 or G8 mice on B6, Balb/c or β2M−/− background were obtained by proper crossing. One CCR10-knockout/EGFP-knockin allele (CCR10+/EGFP) was also introduced into KN6 or G8 mice of the different backgrounds or mice bearing Skint1FVB(Tac) alleles as a reporter for CCR10 expression (2). All animal experiments were approved by Pennsylvania State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell isolation, antibodies and flow cytometry (FACS)

Isolation of epidermal cells, thymocytes and splenocytes was performed as described (1). Anti-CD3, CD122, CD62L and γδTCR antibodies were from eBioscience; anti-CD24, CCR7 from BioLegend; anti-Vγ2, Vγ3 and α4β7 from BD Bioscience; and anti-CCR9 from R&D Systems. 17D1 antibody was described (9).

Reconstituted fetal thymic organ culture (FTOC)

The experiment was performed as described (10). Rag1−/−γC−/− or 2-deoxyguanosine treated E15 fetal thymic lobes were reconstituted with donor cells of different origins and cultured in vitro.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

The experiment was performed similarly as described (11). Formaldehyde-fixed cells were sonicated to generate fragmented chromatins, which were immunoprecipitated by anti-H3K4me2 or H3K9me3 antibodies (Abcam Inc). DNA purified from the immunoprecipitated samples were analyzed by real-time PCR with primer sets PF:ccaccgtggcgagcaggatg/PR:agccgtgaacccaggagaaaagc for the CCR10 promoter region and CF:gggtgtgggaatgtcttacacggt/CR:ggccattgccagccagaccc for the CCR10 coding region.

Adoptive transfer of fetal thymic γδT cells into recipient mice

The experiment was performed as described (5). Positively selected CD122+ fetal thymic Tg Vγ2+ of B6 background or wild-type Vγ3+ γδT cells were injected intraperitoneally into 2–3 day old newborn mice. Two months after the transfer, recipients were analyzed.

In situ staining of epidermal sheets and fluorescent microscopy

The experiment was performed as previously described (5). Ear epidermal sheets were fixed, and stained with fluorescently labeled anti-Vγ3 or Vγ2 antibodies and, if for TUNEL staining, an in situ cell death detection kit (TMR red) (Roche Applied Science). The stained sheets were analyzed by fluorescent microscopy.

Results and Discussion

Impaired selection promotes acquisition of different homing properties by fetal thymic Vγ3+ T cells

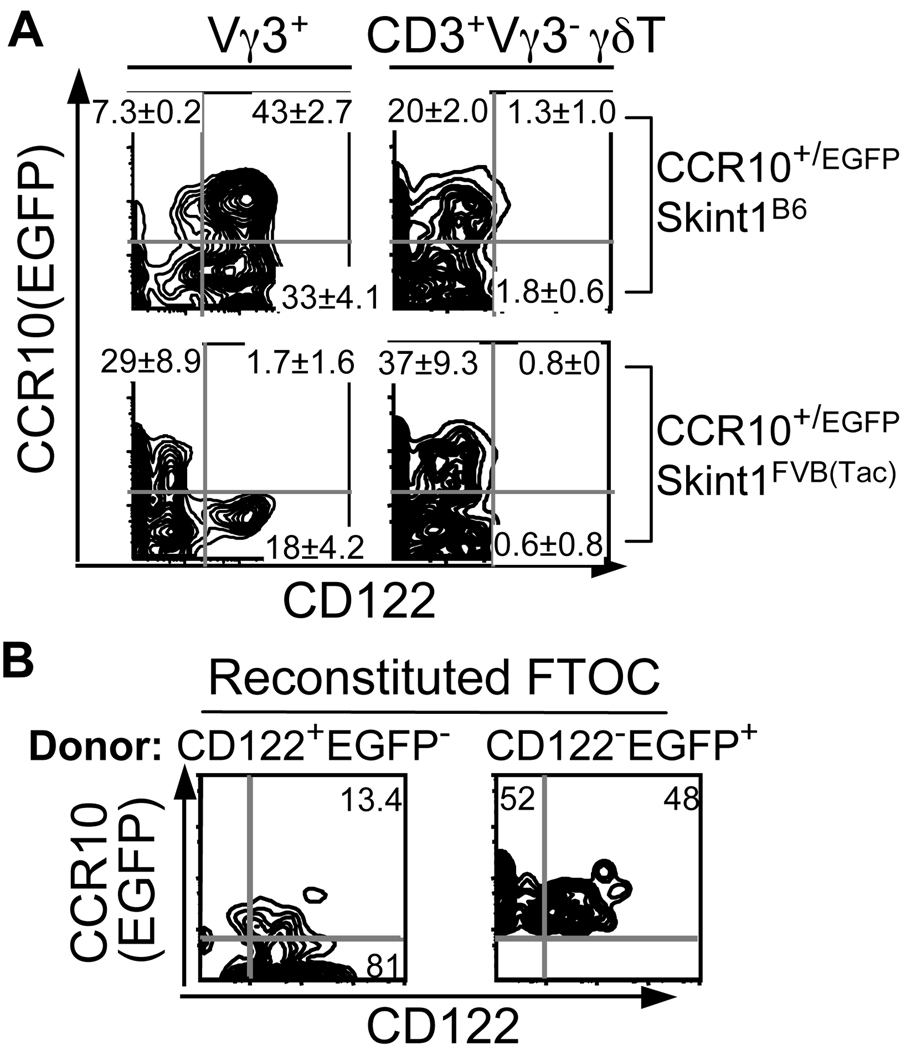

To dissect how selection is involved in the acquisition of the skin-homing property by fetal thymic Vγ3+ T cells, we analyzed their differentiation in mice bearing the mutant Skint1FVB(Tac) gene (6). In contrast to those of wild type Skint1B6 background, Vγ3+ fetal thymocytes of Skint1FVB(Tac) background could not develop into the mature CD122+CCR10+ stage that is associated with a unique homing molecule pattern (CCR10+CCR9−CCR7−CD62Llowα4β7−) and the ability to home to the skin (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1)(2). Instead, many Vγ3+ fetal thymocytes of Skint1FVB(Tac) background differentiated into a CD122−CCR10+ population with a homing molecule expression pattern similar to that of Vγ3− γδT cells (CCR9+CCR7+CD62Lhighα4β7+). Consistent with their altered homing property, Vγ3+ cells were found in tissues other than the skin, such as the uterus, in FVB(Tac) mice (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Impaired selection of Vγ3+ fetal thymocytes results in their acquisition of a different homing property. A. FACS analysis of CCR10(EGFP) and CD122 expression on E16 fetal thymic Vγ3+ vs. Vγ3− T cells of CCR10+/EGFP mice of Skint1B6 or Skint1FVB(Tac) background (N≥5 each). B. FACS analysis of Vγ3+ cells recovered from five-day in vitro cultured E15 fetal B6 thymic lobes reconstituted with fetal thymic CD122+CCR10− or CD122−CCR10+ Vγ3+ cells of CCR10+/EGFPSkint1FVB(Tac) mice. N≥3 for each type.

The CD122−CCR10+ or CD122+CCR10− Vγ3+ fetal thymocytes of Skint1FVB(Tac) background differentiated into the CD122+CCR10+ stage when reconstituted and cultured in fetal thymic lobes of B6 mice bearing a wild-type Skint1 (Fig. 1B), confirming that a unique selection is required for acquisition of the skin-homing property by the Vγ3+ cells.

A strong γδTCR signal promotes fetal thymic transgenic Vγ2+T cells to acquire the Vγ3-like skin-homing property

To assess how the TCR signalling is involved in acquisition of the skin-homing property, we tested whether γδT cell subsets that normally do not localize to the skin could acquire the unique skin-homing property if provided different TCR signals. For this purpose, we used two well-studied Vγ2+ γδTCR Tg mice, G8 and KN6 (7, 8). Both G8 and KN6 γδTCRs recognize ligands T10/22, two non-classic MHC molecules encoded in the H-2 allele that are expressed highly in B6 (H-2b), low in Balb/c (H-2d) but not in β2M−/− mice (12). Since Vγ2+ T cells are normally generated in adult thymi and preferentially localize into SLOs, these Tg mice also allow us to compare how fetal and adult thymic Tg γδT cells are selected to acquire specific homing properties.

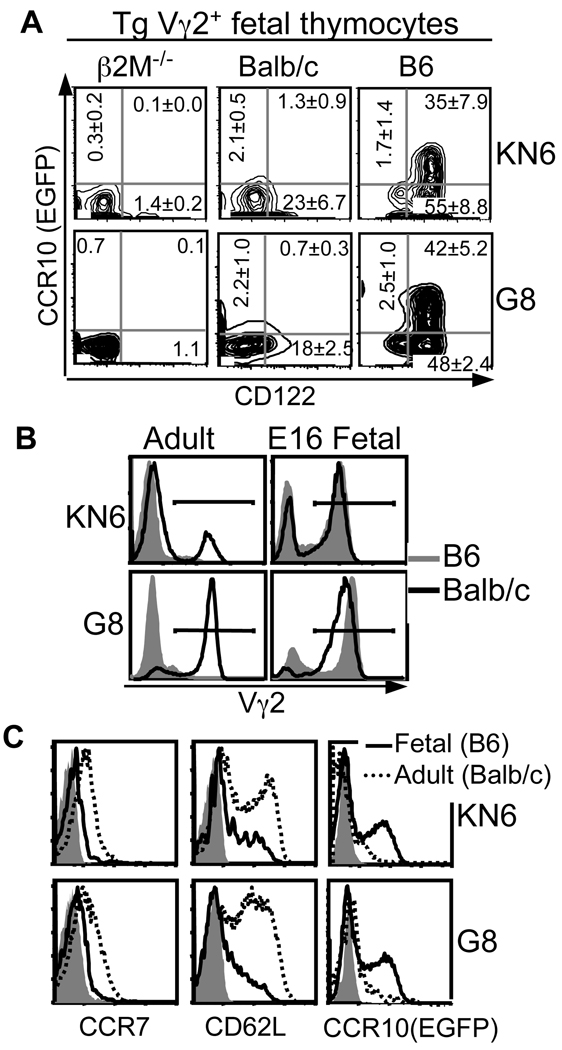

Only on the ligand-high B6 background did the fetal thymic G8 or KN6 γδT cells undergo a developmental process same as the Vγ3+ sIEL precursors to reach the mature CD122+CCR10+ stage (CD24−CD62LlowCCR7−) (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 3), demonstrating that a strong γδTCR signal promotes positive selection associated acquisition of the skin-homing property in fetal thymic γδT cells, irrespective of γδTCR composition. The Tg γδT cells of ligand-low Balb/c background showed signs of partial selection, such as the moderate CD122 upregulation and CD62L downregulation, but could not reach the CD122+CCR10+ stage.

Figure 2.

A strong γδTCR signal promotes acquisition of the Vγ3-like skin-homing property by fetal thymic Tg Vγ2+ T cells. A. FACS analysis of CD122 and CCR10(EGFP) expression on E16-17 fetal KN6 or G8 Tg Vγ2+ thymocytes of different ligand-expressing backgrounds. At least two mice of each genotype were analyzed with the same results. B. FACS analysis of fetal vs. adult thymocytes for Tg Vγ2+ T cells in G8 or KN6 mice of B6 or Balb/c background. The histographs are gated on total thymocytes. N≥3. C. FACS analysis of fetal vs. adult G8 or KN6 Tg γδT cells of indicated backgrounds for the expression of different homing molecules. Histographs were gated on Vγ2+ cells. Gray areas were isotype controls.

Unlike their fetal counterparts, adult thymic G8 or KN6 γδT cells of B6 background were negatively selected (Fig. 2B)(8). While the adult thymic Tg γδT cells of Balb/c background were not negatively selected, they preferentially expressed homing molecules characteristic of the SLO localization, such as CCR7 and CD62L, but no or low CCR10 (Fig. 2C). Therefore, T cells bearing identical γδTCRs, if generated at different ontogenic stages and/or selected in different thymic environments, acquire different homing properties.

The skin-homing potential is intrinsically programmed in fetal thymic γδT cells before the γδTCR-mediated selection

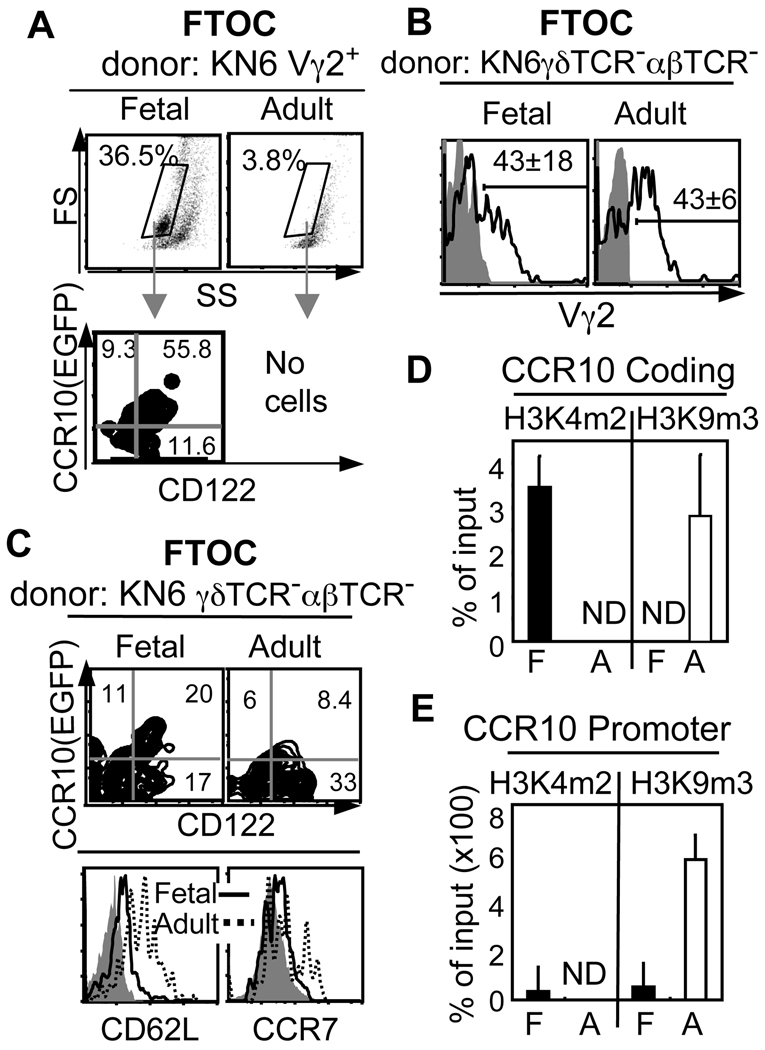

To dissect mechanisms underlying the selective acquisition of skin-homing property by the fetal thymic γδT cells, we reconstituted B6 fetal thymic lobes with purified un-selected adult or fetal thymic KN6 Vγ2+ T cells for FTOC cultures. While the fetal donor cells differentiated efficiently into the CD122+CCR10+ stage, few cells could be recovered from lobes reconstituted with the adult donors (Fig. 3A). These results are consistent with the notion that adult thymic γδT cells are negatively selected in the ligand-high environment and suggest that intrinsic properties of fetal and adult thymic γδT cells play an important role in their selection consequences. To dissect this further, we reconstituted B6 fetal thymic lobes with earlier-stage γδTCR−αβTCR− adult or fetal thymic progenitors of KN6 mice. In this scheme, KN6 γδT cells were efficiently generated of both adult and fetal donors (Fig. 3B). However, KN6 γδT cells of the adult donors still preferentially expressed the molecules associated with the SLO localization (CD62L+CCR7+CCR10low/−) while those of the fetal donors displayed the unique skin-homing property (CD122+CCR10+) (Fig. 3C), indicating that the skin-homing potential is intrinsically programmed in the fetal thymic progenitors even before the TCR-mediated selection.

Figure 3.

Intrinsic properties of fetal vs. adult thymic KN6 γδT cells determine their different selection and differentiation processes. A. FACS of thymocytes of a five-day FTOC reconstituted with purified fetal thymic CD122−CCR10(EGFP)− or adult thymic CD24highCCR10(EGFP)− Tg Vγ2+ cells of CCR10+/EGFPβ2M−/−KN6 mice. The gated regions in the top panels represent total thymocytes that are all of the Tg Vγ2+ donor origin, whose expression of CD122 and CCR10(EGFP) is shown in the bottom panels. N≥5. B. FACS analysis of thymocytes recovered from ten-day B6 FTOC reconstituted with purified E15 fetal or adult thymic αβTCR−γδTCR− progenitor cells of CCR10+/EGFPKN6 (B6) mice for the Tg Vγ2+ T cells. N≥ 5. C. FACS analysis of the Tg Vγ2+ T cells gated from the panel B for different homing molecules. N≥4. D–E. ChIP analyses of H3K4m2 and H3K9m3 modifications at the CCR10 locus in purified fetal EGFP(CCR10)−CD122− and adult CD24hiCD4−CD8− Vγ2+ thymocytes of CCR10+/EGFPβ2M−/−KN6 mice. N ≥2. ND: non-detectable. F: fetal. A: adult.

To gain insight into a molecular basis underlying the intrinsically programmed skin-homing potential in fetal thymic γδT cells, we assessed epigenetic modifications of CCR10 locus in un-selected fetal and adult thymic KN6 γδT cells of β2M−/− background, which do not express CCR10 at all (Fig. 2A). Levels of di-methylated lysine4 of histone 3 (H3K4m2), a modification correlating with gene activation, and tri-methylated lysine9 of histone 3 (H3K9m3), a modification implicated in gene silencing, were determined by a ChIP assay (11, 13). Compared to their adult counterparts, the fetal thymic Tg γδT cells had higher levels of H3K4m2 and lower levels of H3K9m3 at both CCR10 promoter and coding regions (Fig. 3D–E), all suggesting that the fetal cells have a more active CCR10 locus. These results indicate that before its expression, CCR10 locus is already in an “OPEN” and transcription permissive configuration in the fetal, but not adult, thymic γδT cells, suggesting that it is programmed for different expression potentials.

Positively selected fetal thymic γδT cells develop into sIELs without requirement of peripheral TCR/ligand interaction

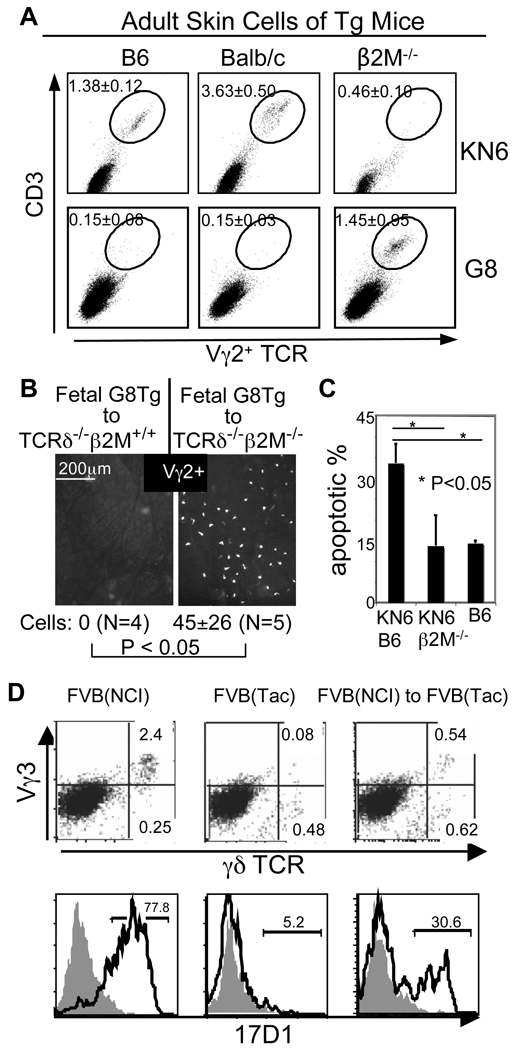

Different from Vγ3+ cells, the positive selection and skin-homing properties of the fetal thymic Tg Vγ2+ T cells were not associated with the efficient development of Tg Vγ2+ sIELs (Fig. 4A). There were nearly no Tg sIELs in adult G8(B6) mice while β2M−/−G8 mice had many. KN6(B6) mice also had fewer sIELs than KN6(Balb/c) mice. The development of Tg sIELs in G8 vs. KN6 mice of same backgrounds was also different. For example, there were more Tg sIELs in β2M−/−G8 mice than in β2M−/−KN6 mice.

Figure 4.

Positively selected fetal thymic γδT cells develop into sIELs without the requirement of peripheral TCR/ligand interaction. A. FACS analysis of epidermal cell preparations for the Tg Vγ2+ sIELs in adult G8 and KN6 mice of different ligand backgrounds. N≥4 per genotype. B. Immunofluorescent microscopy of ear epidermal sheets of TCRδ−/−β2M−/−B6 or TCRδ−/−B6 mice adoptively transferred with positively selected fetal thymic Tg γδT cells of G8 (B6) mice for the Tg Vγ2+ sIELs. C. High percentages of apoptotic Tg Vγ2+ sIELs in KN6 mice of B6 background. The percentages of apoptotic sIELs are of total sIELs based on in situ TUNEL analyses of ear epidermal sheets (N=4 each). D. FACS analysis of epidermal cell preparations for Vγ3+ sIELs in FVB(Tac) mice transferred with FVB(NCI) fetal thymic γδT cells (top panels). Increased percentages of the epidermal Vγ3+ cells expressing the “sIEL-specific” 17D1-epitope on gated γδTCR+ populations confirmed the reconstitution (bottom) (9). The data is representative of at least 3 experiments.

Several factors might contribute to these complex phenotypes. First, although a strong γδTCR/ligand signal promotes acquisition of the skin-homing property in fetal thymic γδT cells, peripheral TCR/ligand interaction might also affect their development into sIELs. A ligand for G8 and KN6 γδTCRs is expressed in the skin of B6, but not Balb/c, mice (12). Complicating the issue, G8 γδTCR has a higher affinity for the ligand than KN6 γδTCR (14) and they could possibly have additionally different ligands, which altogether would result in the phenotypic difference between G8 and KN6 mice. Furthermore, adult thymic Tg γδT cells might contribute to sIELs. In fact, γδT cells of adult SLOs could migrate into the skin in absence of normal sIELs (15). Therefore, correlation between positive selection of the fetal thymic Tg γδT cells and their development into sIELs could not be directly assessed in the Tg mice.

We therefore transferred positively selected fetal thymic G8 or KN6 γδT cells of B6 background into ligand-negative TCRδ−/−β2M−/−B6 or ligand-high TCRδ−/−B6 mice, which lack endogenous γδT cells. The transferred G8 γδT cells developed into sIELs only in the ligand-negative recipients (Fig. 4B). The transferred KN6 γδT cells also developed efficiently into sIELs in the ligand-negative recipients although some KN6 sIELs developed in the ligand-high recipients (Supplementary Fig. 4A). These results demonstrate that 1) the positively selected fetal thymic Tg γδT cells could develop into sIELs without requirement of peripheral TCR/ligand interaction and 2) continuous peripheral TCR/ligand interaction impairs the sIEL development, likely due to activation-induced apoptosis. Consistent with this, there were higher percentages of apoptotic sIELs in KN6 mice of B6 background than in β2M−/−KN6 or wild type mice (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. 5). The extents of impairment of the G8 or KN6 sIEL development in the ligand-high recipients are also consistent with this conclusion in that a higher G8TCR/ligand affinity is associated with no G8 sIELs while the lower KN6TCR/ligand affinity is associated with the reduced KN6 sIELs. Un-selected fetal thymic Tg γδT cells could not develop into sIELs in any recipients (Supplementary Fig. 4B), confirming that the positive selection is a pre-requisite for their development into sIELs. Together, these results demonstrate that the positive selection of fetal thymic γδT cells is necessary and sufficient for their development into sIELs. Further supporting this, transferred positively selected fetal thymic Vγ3+ γδT cells of Skint1-sufficient FVB(NCI) mice developed into sIELs in Skint1-deficient FVB(Tac) recipients (Fig. 4D).

Conclusion remarks

Proper localization of various T cell subsets in specific tissues is important in the local protection but mechanisms regulating the process are unclear. We here identify an intrinsically programmed process in the fetal thymus that determines selective acquisition of the skin-homing property by the sIEL precursors. This finding could provide a guide in understanding development of other tissue-resident T cells. Our findings on the differential selection processes of the fetal vs. adult thymic Tg γδT cells also help in understanding roles of TCR signals in the γδT cell development, a poorly understood question. Early suggestion on requirement of TCR signals for positive selection of the adult thymic Tg γδT cells (16) was later attributed to negative selection or genetic background (17). However, a recent study found that KN6 γδT cells divert to αβT cell lineage on β2M−/− background (18), suggesting requirement of γδTCR signals for the γδT cell development. In light of our findings, it is likely that different γδT cell subsets have differential requirements of TCR signals for their development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs. David Raulet, Jianke Zhang and Avery August for comments and Priyadarshini Karmarkar for the Skint1genotyping.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (N.X) and, in part, under a grant with the Pennsylvania Department of Health using Tobacco Settlement Funds (N.X.). The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Xiong N, Kang C, Raulet DH. Positive selection of dendritic epidermal γδ T cell precursors in the fetal thymus determines expression of skin-homing receptors. Immunity. 2004;21:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin Y, Xia M, Sun A, Saylor C, Xiong N. CCR10 is important for the development of skin-specific γδT cells by regulating their migration and location. J Immunol. 2010 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001612. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staton TL, Habtezion A, Winslow MM, Sato T, Love PE, Butcher EC. CD8+ recent thymic emigrants home to and efficiently repopulate the small intestine epithelium. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:482–488. doi: 10.1038/ni1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen KD, Shin S, Chien YH. Cutting edge: γδ intraepithelial lymphocytes of the small intestine are not biased toward thymic antigens. J Immunol. 2009;182:7348–7351. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xia M, Qi Q, Jin Y, Wiest DL, August A, Xiong N. Differential roles of IL-2-inducible T cell kinase-mediated TCR signals in tissue-specific localization and maintenance of skin intraepithelial T cells. J Immunol. 184:6807–6814. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyden LM, Lewis JM, Barbee SD, Bas A, Girardi M, Hayday AC, Tigelaar RE, Lifton RP. Skint1, the prototype of a newly identified immunoglobulin superfamily gene cluster, positively selects epidermal γδ T cells. Nat Genet. 2008;40:656–662. doi: 10.1038/ng.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishida I, Verbeek S, Bonneville M, Itohara S, Berns A, Tonegawa S. T-cell receptor γδ and γ transgenic mice suggest a role of a γ gene silencer in the generation of αβ T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:3067–3071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.8.3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dent AL, Matis LA, Hooshmand F, Widacki SM, Bluestone JA, Hedrick SM. Self-reactive γδ T cells are eliminated in the thymus. Nature. 1990;343:714–719. doi: 10.1038/343714a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mallick-Wood C, Lewis JM, Richie LI, Owen MJ, Tigelaar RE, Hayday AC. Conservation of T cell receptor conformation in epidermal γδ cells with disrupted primary Vγ gene usage. Science. 1998;279:1729–1733. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coligan J, Kruisbeek A, Margulies D, Shevach E, Strober W. Current Protocols in Immunology. New York: Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li P, Yao H, Zhang Z, Li M, Luo Y, Thompson PR, Gilmour DS, Wang Y. Regulation of p53 target gene expression by peptidylarginine deiminase 4. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4745–4758. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01747-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito K, Van KL, Bonneville M, Hsu S, Murphy DB, Tonegawa S. Recognition of the product of a novel MHC TL region gene (27b) by a mouse γδ T cell receptor. Cell. 1990;62:549–561. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90019-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams EJ, Strop P, Shin S, Chien YH, Garcia KC. An autonomous CDR3δ is sufficient for recognition of the nonclassical MHC class I molecules T10 and T22 by γδ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:777–784. doi: 10.1038/ni.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Girardi M, Lewis J, Glusac E, Filler RB, Geng L, Hayday AC, Tigelaar RE. Resident skin-specific γδ T cells provide local, nonredundant regulation of cutaneous inflammation. J Exp Med. 2002;195:855–867. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells F, Tatsumi Y, Bluestone J, Hedrick S, Allison J, Matis L. Phenotypic and functional analysis of positive selection in the γδ T cell lineage. J. Exp. Med. 1993;177:1061–1070. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schweighoffer E, Fowlkes BJ. Positive selection is not required for thymic maturation of transgenic γδ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:2033–2041. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haks MC, Lefebvre JM, Lauritsen JP, Carleton M, Rhodes M, Miyazaki T, Kappes DJ, Wiest DL. Attenuation of γδTCR signalling efficiently diverts thymocytes to the αβ lineage. Immunity. 2005;22:595–606. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.