Abstract

A growing body of evidence points toward activated fibroblasts, also known as myofibroblasts, as one of the leading mediators in several major human pathologies including proliferative fibrotic disorders, invasive tumor growth, rheumatoid arthritis, and atherosclerosis. Niemann-Pick Type C2 (NPC2) protein has been recently identified as a product of the second gene in NPC disease. It encodes ubiquitous, highly conserved, secretory protein with the poorly defined function. Here we show that NPC2 deficiency in human fibroblasts confers their activation. The activation phenomenon was not limited to fibroblasts as it was also observed in aortic smooth muscle cells upon silencing NPC2 gene by siRNA. More importantly, activated synovial fibroblasts isolated from patients with rheumatoid arthritis were also identified as NPC2-deficient at both the NPC2 mRNA and protein levels. The molecular mechanism responsible for activation of NPC2-null cells was shown to be a sustained phosphorylation of ERK 1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), which fulfills both the sufficient and necessary fibroblast activation criteria. All of these findings highlight a novel mechanism where NPC2 by negatively regulating ERK 1/2 MAPK phosphorylation may efficiently suppress development of maladaptive tissue remodeling and inflammation.

Keywords: Cellular Regulation, Fibroblast, Inflammation, Innate Immunity, Signal Transduction

Introduction

Somatic cell plasticity, especially that of skin fibroblasts, was brought into the spotlight after discovery of induced cell pluripotency (1, 2). The interest in skin fibroblast plasticity has gained additional momentum after a recent report describing direct conversion of mouse skin fibroblasts into functional neurons upon their transfection with defined factors (3). Such new and exciting developments were not entirely surprising as it has been known for quite some time that fibroblasts and mesenchymal stem cells share many specific properties and markers (4). Yet freshly isolated but not repeatedly subcultured adult human skin fibroblasts displayed the ability to (trans)differentiate along the mesodermal and endodermal lineages (5, 6).

Activated fibroblasts (AF),2 also known as myofibroblasts, play a pivotal role in tissue repair and regeneration (7, 8). They are not only important for survival and self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells (9) but were also shown to have mesenchymal stem cell-like properties that could be maintained in culture for a prolonged time (10, 11). However, uncontrolled and persistent fibroblast activation is a leading cause in the development of several major human pathologies including tissue fibrosis (12–14), invasive tumor growth (15), and rheumatoid arthritis (16). AF and smooth muscle cells (SMC) also represent a major underlying cause in maladaptive vessel wall remodeling induced by hypertension, atherosclerosis, and angioplasty (17–20).

As an essential intermediary in the above processes, AF display a distinct phenotype that is characterized by the up-regulated expression of contractile proteins, such as myosin heavy polypeptides, α(γ)-smooth muscle actin, vimentin, and tropomyosin (21–23). In addition, AF demonstrate increased production and secretion of inflammatory cytokines and growth factors, including IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, TGF-β, basic FGF, PDGF, and VEGF (15, 24, 25). One of the least appreciated AF features is their remarkable ability to clear bacteria, microbes, and apoptotic cells through phagocytosis, thus, providing immune protection and resolution of inflammation (26–29).

Although a close link has been clearly established between initiation of maladaptive tissue remodeling and fibroblast activation (30), much less known about the molecular mechanism(s) underlying fibroblast activation. The most studied and understood mechanism associated with fibroblast activation is the induction of the TGF-β1 signaling network (31) where sustained activation of ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) provides both sufficient and necessary conditions for fibroblast activation (32–34). While performing DNA microarray analysis of human dermal fibroblasts bearing nonsense mutations in the second gene of Niemann-Pick type C disease, NPC2, we noticed a striking up-regulation of the activated fibroblast markers. This observation prompted us to explore in detail a potential role for NPC2 protein in regulation of fibroblast activation.

NPC disease is an autosomal recessive disorder where mutations in at least two independent genes, NPC1 and NPC2, are responsible for the pathologic changes in the liver, lungs, and the brain of patients that leads to their premature death (35). The function of these genes is not yet well understood. The NPC1 product was thought to regulate cholesterol mobilization of intracellular cholesterol to the plasma membrane (36–38), although this view has been recently challenged (39, 40). Yet during the past few years the NPC1 research field has progressed quickly, and new functions of this protein have been uncovered that extend beyond cholesterol trafficking. They include maintenance of embryonic stem cells (41), regulation of oncogenesis (41, 42), intracellular transport of copper (43) and fatty acids (44), late endosome/lysosome fusion (45), and lysosomal amine regulation (46).

The NPC2 protein was originally characterized as the major secretory protein of epididymal fluid (HE1) (47) and was later linked to the second NPC disease locus, the NPC2 gene (48), which encodes ubiquitous 14–18-kDa protein with poorly defined function. NPC2 is highly conserved among the major species, has a striking structural resemblance to the dust mite allergen Der p 2 (49), and is also found in large quantities in milk, bile, and plasma (49, 50). NPC2 binds cholesterol with the high affinity (51) and was implicated in mediating intracellular cholesterol trafficking through the late endosomal/lysosomal compartment (for review, see Ref. 52). However, NPC2 mutants with almost zero cholesterol binding activity (2–7% of control level) were able to normalize cholesterol content and distribution in ∼50% of NPC2-null fibroblasts (51), which points strongly toward the existence of cholesterol-independent mode of action for NPC2. Consistent with this notion, NPC2 protein has been shown recently to play an important role in regulation of hematopoiesis (53) and immunity (54), where it performs the respective functions independently of its cholesterol binding ability. Intriguingly, the clinical phenotype of NPC disease patients associated with mutations in the NPC2 gene is characterized by pronounced pulmonary fibrosis (55–57), known to be primarily mediated by AF (12). In fact, respiratory and(or) liver failure is reported to be the major cause of patient deaths and occurs before the development of neurologic symptoms (55, 57). This implicates fibroblast activation in disease pathogenesis.

In the present study we demonstrate that the loss of NPC2 protein in primary human fibroblasts resulted in their activation. To determine whether alteration in NPC2 expression is a more general characteristic of AF in human disease, we examined synovial fibroblasts (SF) from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). RA is characterized by SF that develop an activated phenotype associated with massive proliferation and destruction of articular cartilage and juxta-articular bone. We showed that SF isolated from patients with RA were NPC2-deficient as reflected by their drastic reduction of both the NPC2 mRNA and protein levels. The molecular mechanism responsible for activation of NPC2-null fibroblasts was identified by detecting sustained ERK1/2 MAPK phosphorylation, which fulfills both the sufficient and necessary fibroblast activation criteria (32–34). Therefore, our studies highlight a novel mechanism where NPC2 protein regulates maintenance of the basal, non-activated fibroblast state through suppression of sustained ERK 1/2 MAPK phosphorylation. Altogether, our studies begin to unveil a novel and important role for NPC2 protein in regulation of maladaptive tissue remodeling and development of systemic inflammatory disorders.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, fetal bovine serum, glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin were obtained from Cellgro. Alexa Fluor488-conjugated acetylated human LDL (Alexa-AcLDL) was purchased from Molecular Probes. Rabbit polyclonal, mono-specific antibody against human NPC2 was obtained from Atlas.

Cell Lines

Normal skin fibroblasts (CRL-1474) were obtained from ATCC. NPC2-null human dermal fibroblasts were described elsewhere (58, 59). Human aortic smooth muscle cells were obtained from Cambrex and cultured in the media provided by the same supplier. Primary AF were isolated from synovial tissue (60, 61) procured from anonymous patients undergoing clinically indicated orthopedic surgery for the management of RA. Experimental protocols were approved by the institutional review board of the University of Kentucky.

DNA Microarray Assay

Total RNA was isolated from the normal and NPC2-null confluent cells that were cultured under normal conditions (58, 59) by using the Qiagen RNeasy kit following the manufacturer instructions. Samples were hybridized to the human U133A microarray (Affimetrix) by the Alvin Siteman Cancer Center's Multiplexed Gene Analysis Core at the Washington University in St. Louis. Signal intensity ratios of >2-fold (up-regulated) or <2-fold (down-regulated) in at least two trials were considered regulated. Expression of the genes that were undetectable in the wild type cells and were only present in NPC2-null fibroblasts was termed “induced.”

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA from normal and NPC2-deficient human skin fibroblasts was quantitatively converted into the single-stranded cDNA by using High Capacity cDNA Archive kit (Applied Biosystems). The particular genes were detected using the respective TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) on the 7300 Real-time RT-PCR system from the same manufacturer by relative quantitation employing β-glucuronidase (GUSB) as the reference gene.

Cytokine ELISA Assay

IL-6 and IL-1 were measured in the conditioned medium from non-elicited human fibroblasts cultured under the normal conditions using the respective RayBio human ELISA kits from RayBiotech. Sample manipulations, detection, and quantification were conducted according to the manufacturer instructions.

NF-κB Activity Measurement

Cell nuclear extracts were isolated from normal and NPC2-mutant human fibroblasts using the nuclear/cytosol fractionation kit from BioVision. NF-κB activity was assessed by using TransBinding NF-κB assay kit from Panomics. This kit detects binding of p50 NF-κB subunit to an oligonucleotide containing a NF-κB binding consensus that is immobilized on the 96-well plate. Activated NF-κB p50 from cell nuclear extracts specifically binds to this oligonucleotide. The complex bound to the oligonucleotide is detected by antibody directed against the p50 subunit. An additional secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody provides sensitive colorimetric readout easily quantified by spectrophotometry. Sample manipulation, detection, and quantification were performed according to the manufacturer instructions.

AcLDL Uptake Measurement

Normal and NPC2-null fibroblasts grown in 96-well plates under the normal conditions were washed three times with PBS and incubated with different concentrations of Alexa-AcLDL (see above) dissolved in the same buffer for 1 h at 37 °C. After the incubation, cells were washed three times with the ice-cold PBS, and the respective wells were filled with the same buffer. Cell-bound AcLDL was assayed by measuring absorption at 488 nm as recommended by the manufacturer using Tecan GENios multimode microplate reader. The AcLDL signal in each well was normalized to its respective protein content that was determined using the CBQCA protein quantitation kit from Molecular Probes.

Phagocytic Activity Assay

Phagocytic potential of normal and NPC2-null cells was assessed by using Vybrant Phagocytosis Assay kit from Molecular Probes following the manufacturer's instructions. This assay is based on the uptake of fluorescein-labeled Escherichia coli (K-12 strain) BioParticles® by cultured cells where fluorescence of non-internalized bacterial particles was quenched by toluidine blue.

Cell migration was assessed by employing a QCM chemotaxis 8-μm 24-well cell migration assay from Chemicon according to the manufacturer's protocol. Chemotactic gradient was created by adding 10 ng/ml PDGF-BB to the bottom chamber.

ERK 1/2 Activation

NPC2-null human fibroblasts were cultured under the normal conditions as previously described (58, 59), and both the cytosolic and nuclear protein fractions were isolated from the ∼90%-confluent cells using the nuclear/cytosol fractionation kit from BioVision according to the manufacturer's instructions. The total (catalog #9102) and phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204, catalog #9101) were probed by Western blotting using highly specific primary mouse monoclonal and rabbit polyclonal antibodies from Cell Signaling. That was followed by the incubation with the Alexa Fluor 680 goat anti-mouse (Molecular Probes) and IRDye800CW goat anti-rabbit (Rockland) affinity-purified IgG, respectively. Protein bands were identified on the same membrane by simultaneous, dual-color scanning using the LI-COR Odyssey near-infrared imaging system.

NPC2 gene silencing by siRNA was performed as follows. The complimentary mRNA nucleotides derived from the human NPC2 sequence (Ambion, siRNA ID #18116) were transfected into human fibroblasts or primary human aortic SMC (Cambrex) plated onto a 96-well cell culture vessel using jetSI-ENDO Polyplus Transfection according to the manufacturer's instructions. The fluorescent derivative of the same transfection reagent, jetSI-ENDO-Fluo (Polyplus Transfection), was used in the parallel experiment to measure cell transfection efficiency. The extent of the gene silencing was assessed by real-time RT-PCR. To that end, total RNA was extracted from the control and transfected cells using the Qiagen RNeasy micro kit following the manufacturer instructions and was quantitatively converted into the single-stranded cDNA by using the High Capacity cDNA Archive kit (Applied Biosystems). The NPC2 gene was detected using the respective TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems) on the 7300 Real-Time RT-PCR system from the same manufacturer by relative quantitation employing β-glucuronidase (GUSB) as the reference gene. The optimized transfection protocol, which utilized 50 nm siRNA, demonstrated ≥90% transfection efficiency and ∼70% reduction in NPC2 gene expression after 24 h. It should be noted that siRNA transfection caused no detectable effect on cell viability.

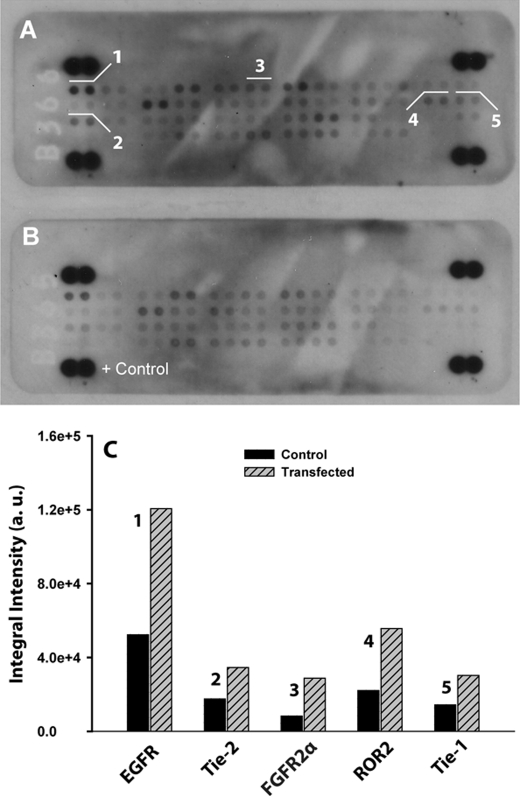

Activation Status of the membrane-bound receptor-tyrosine kinase (RTK)/growth factor receptor (GFR) was probed with human phospho-receptor-tyrosine kinase array kit from R & D Systems. The array is capable of simultaneously identifying the relative phosphorylation levels of 42 different RTKs. The sensitivity of the array is 2–20-fold higher as compared with the immunoprecipitation/Western blot analysis. To that end, normal and NPC2-null human skin fibroblasts were cultured under the normal conditions and lysed using BioVision nuclear/cytosol fractionation kit supplemented with 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin. Cytosolic fractions of the cell lysates (100 μg) isolated from normal and NPC2-null cells were simultaneously applied to and incubated with the respective array nitrocellulose membranes containing capture and control antibodies. After binding the extracellular domain of both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated RTKs, unbound material was washed away. A pan phosphotyrosine antibody conjugated to HRP was used to detect phosphotyrosines on activated receptors by chemiluminescence. Signals from particular RTKs were identified according to the array map. Semiquantitative analysis of the respective signals was performed following the manufacturer's recommendation with the assistance of Adobe Photoshop CS4 Extended software.

RESULTS

NPC2 Deficiency Confers Fibroblast Activation

Transcriptional profiling of NPC2-mutant fibroblasts by DNA microarray demonstrated clearly either induced or up-regulated expression pattern of several gene family members that are characteristic of AF (Table 1). The most specific markers among these genes are MYH1, PDGFD, VEGFB, IL-1B, and IL-6 (24, 25). We use the term “induced” to define expression of the genes that were undetectable in the wild type cells and were only present in NPC2-null fibroblasts. To confirm differential expression of specific genes in human fibroblasts, we performed analysis of the respective mRNA transcripts by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 1A). As in this figure, the respective data were in the excellent agreement with those of DNA microarray set (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Transcriptional signature of NPC2-null human fibroblasts as probed by DNA microarray; activated fibroblast markers

| Probe set | Gene name | Symbol | Gene expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeleton proteins | |||

| 205951_at | Myosin, heavy polypeptide 1, skeletal muscle, adult | MYH1 | Induceda |

| 202274_at | Actin, γ2, smooth muscle, enteric | ACTG2 | Induced |

| Extracellular matrix proteins | |||

| 213451_x_at | Tenascin XB | TNXB | Induced |

| 201787_at | Fibulin 1 | FBLN1 | Induced |

| 203477_at | Collagen, type XV, α1 | COL15A1 | Induced |

| 37892_at | Collagen, type XI, α1 | COL11A1 | Induced |

| 218975_at | Collagen, type V, α3 | COL5A3 | Induced |

| 213110_s_at | Collagen, type IV, α5 (Alport syndrome) | COL4A5 | Induced |

| 212940_at | Collagen, type VI, α1 | COL6A1 | ↑ 1.9 |

| 202311_s_at | Collagen, type I, α1 | COL1A1 | ↑ 1.6 |

| 213790_at | A disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 12 (meltrin α) | ADAM12 | ↑ 2.3 |

| 206046_at | A disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 23 | ADAM23 | Induced |

| Growth factors | |||

| 219304_s_at | Platelet-derived growth factor D | PDGFD | ↑ 7.0 |

| 203683_s_at | Vascular endothelial growth factor B | VEGFB | Induced |

| 205767_at | Epiregulin | EREG | Induced |

| 206404_at | Fibroblast growth factor 9 (glia-activating factor) | FGF9 | Induced |

| Scavenger receptors | |||

| 209555_s_at | CD36 antigen (collagen type I receptor, thrombospondin receptor) | CD36 | Induced |

| 210004_at | Oxidized low density lipoprotein (lectin-like) receptor 1 | OLR1 (LOX-1) | ↑ 9.8 |

| 214770_at | Macrophage scavenger receptor 1 | MSR1 (SR-A) | Induced |

| Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines | |||

| 39402_at | Interleukin 1β | IL1B | Induced |

| 205207_at | Interleukin 6 (interferon, β2) | IL6 | ↑ 2.5 |

| 204470_at | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (melanoma growth stimulating activity α) | CXCL1 (GRO-α) | ↑ 4.0 |

| 206336_at | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 6 (granulocyte chemotactic protein 2) | CXCL6 | Induced |

| 216598_s_at | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 | CCL2 (MCP-1) | Induced |

a “Induced” in the Gene expression column identifies genes whose expression was undetectable in the wild type cells and were only present in NPC2-null fibroblasts. See text for experimental details.

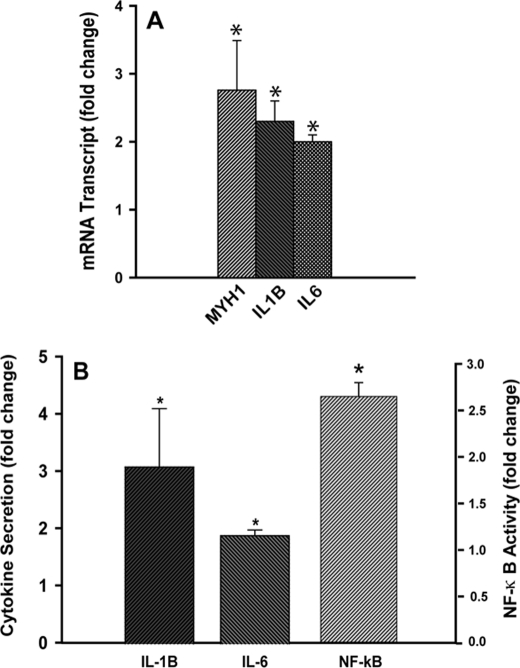

FIGURE 1.

NPC2 deficiency confers fibroblast activation. A, expression of activated fibroblast markers as probed by real-time RT-PCR is shown. IL-6 and IL-1β secretion from non-elicited normal and NPC2-null human fibroblasts as measured by ELISA is shown. B, IL-6 and IL-1β secretion from non-elicited normal and NPC2-null human fibroblasts as measured by ELISA. Data were normalized to their respective control and are shown as the mean ± S.E. (*) depicts p ≤ 0.05 as compared with control (n = 3).

Consistent with the activated fibroblast phenotype, the NPC2-mutant cells were characterized by the increased production and secretion of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and IL-1β (Table 1, Fig. 1, A and B). The increase in production of IL-6 and IL-1β (Table 1) was most likely related to the up-regulated activity of NF-κB as demonstrated in Fig. 1B.

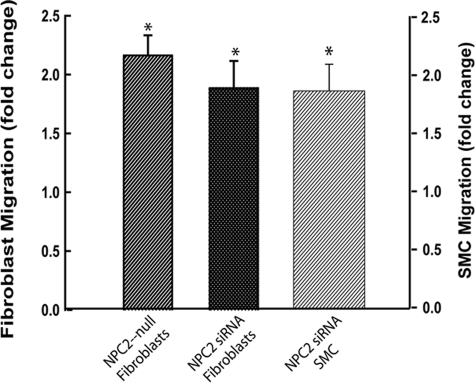

An additional and very important feature of AF is their increased ability to migrate in response to a variety of chemotactic factors, including PDGF-BB, that are released by tissue resident cells after injury (62–64). This feature allows AF to reach a lesion site quickly and initiate repair. We probed migratory activity of NPC2-null fibroblasts by measuring their translocation across the membrane in the Boyden chamber toward the 10 ng/ml PDGF-BB (Fig. 2). Consistent with the AF nature of the NPC2-null cells, their chemotactic activity was increased more than 2-fold as compared with that of normal fibroblasts. The very similar effect was also observed in normal fibroblasts and human aortic smooth muscle cells after silencing NPC2-gene by siRNA (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

NPC2 deficiency results in enhanced cell migration; NPC2 null human dermal fibroblasts or normal human dermal fibroblasts after NPC2 gene silencing by siRNA and aortic SMC after NPC2 gene silencing by siRNA have increased migration toward 10 ng/ml PDGF-BB. Data were normalized to their respective controls and are shown as the mean ± S.E. (*) depicts p ≤ 0.05 as compared with control (n = 3).

Loss of NPC2 Protein in Human Fibroblasts Renders Stimulation of Their Scavenger Receptor Expression and Activity

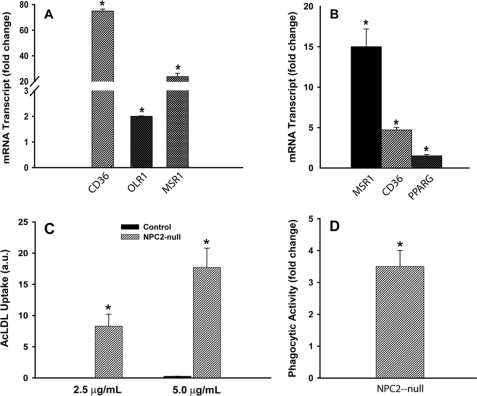

One of the important discoveries in the present study is that NPC2-deficient cells demonstrated increased expression of several membrane scavenger receptors, including CD36, MSR1 (SR-A), and OLR1 (LOX-1) (Table 1). These receptors are the important regulators of innate immunity as well as the providers of modified LDL clearance from circulation. Some of them, CD36 and OLR1, are known to be up-regulated in AF (65–67) where they mediate oxidative stress and fibrogenesis (67, 68). We confirmed up-regulated expression of scavenger receptors in NPC2-null fibroblasts (Table 1) by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 3A) and then reproduced such phenomenon in human aortic SMC by silencing NPC2 gene through siRNA transfection (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Scavenger receptor expression and function in NPC2-null human fibroblasts and aortic SMC. A, scavenger receptor expression and function in NPC2-null human fibroblasts compared with normal human fibroblasts is shown. B, scavenger receptor expression in aortic SMC transfected with NPC2 siRNA is shown. C, binding of modified LDL is shown. a.u., absorbance units. D, phagocytic activity of NPC2-null fibroblasts using fluorescently labeled E. coli particles is shown. Fluorescence of non-internalized particles was quenched by toluidine blue. Data shown are the mean ± S.E. (*) depicts p ≤ 0.05 as compared with control (n = 3).

To assess a functional significance of the scavenger receptor expression in NPC2-deficient cells, we measured their AcLDL binding activity (Fig. 3C). Although normal fibroblasts displayed no such detectable activity, the NPC2-null fibroblasts robustly bound modified LDL. In addition, the NPC2-null fibroblasts had significantly (∼3.5-fold) up-regulated basal phagocytic activity toward the fluorescein-labeled E. coli particles (Fig. 3D). Altogether, these data demonstrate that the up-regulated scavenger receptors in NPC2-null cells are functionally competent.

In summary, based on the specific gene expression pattern (Table 1 and Fig. 1A) and up-regulated cell innate immune response (Table 1, Fig. 1) increased cell chemotactic activity (Fig. 2) as well as up-regulated and functional scavenger receptors (Fig. 3), we conclude that NPC2 deficiency in human fibroblasts is sufficient for fibroblast activation.

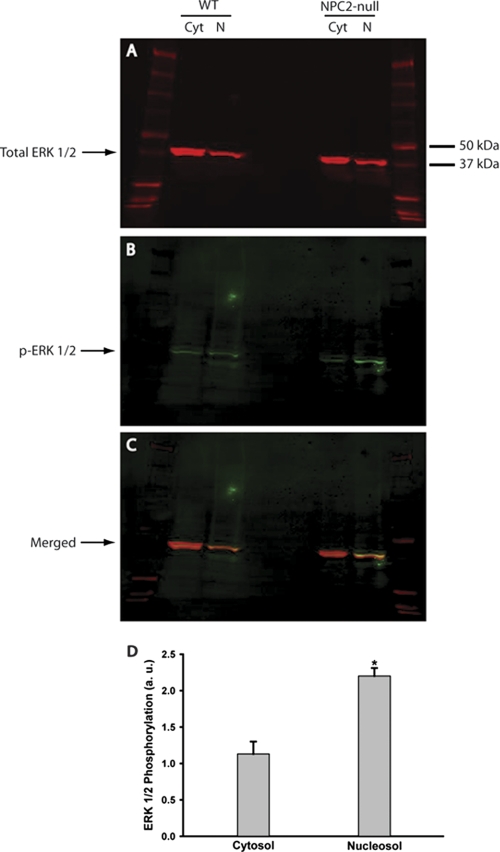

NPC2 Regulates Fibroblast Activation through Suppression of Sustained ERK2 MAPK Activation

To identify the NPC2-dependent mechanism that regulates non-activated cell state, we turned our attention to phosphorylation status of ERK 1/2 MAPK. Sustained phosphorylation of ERK 1/2 has been identified as both the sufficient and necessary pre-requisite of fibroblast activation (32–34) with the ERK 2 isoform being a major driving force (69). We probed the activation status of ERK 1/2 MAPK in non-elicited NPC2-null fibroblasts and found a selective and sustained increase in phosphorylation of ERK 2 isoform (Fig. 4). Most, if not all of the activated ERK2 was found in the nucleosol where its phosphorylation level exceeded that of in normal cells by more than 2-fold (Fig. 4). The sustained increase in the ERK2 activity was also detected in the total cell lysate (supplemental Fig. S1). We conclude that NPC2 protein controls a key regulatory process that is responsible for modulating fibroblast phenotype by suppressing persistent ERK 2 MAPK activation.

FIGURE 4.

Sustained ERK 1/2 activation in NPC2-null human fibroblasts. Total (A) and phosphorylated (activated, B) ERK1/2 were detected by Western blotting in the cytosolic (Cyt) and nuclear protein (N) fractions isolated from the wild type (WT) and NPC2-null fibroblasts. The respective proteins were labeled with the specific sets of primary/fluorescently tagged secondary antibodies and were identified on the same membrane by simultaneous dual-color scanning using the high-resolution LI-COR Odyssey near-infrared imaging system. C, a merged image of A and B demonstrates high specificity of the phospho-ERK1/2 staining. D, quantitative analysis of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in NPC2-null fibroblasts is shown. The intensities of the phosphorylated ERK1/2 bands (B) were measured using the LI-COR Odyssey Version 2.0 software and normalized to that of total ERK1/2 (A). Data are the mean ± S.E. (n = 3). The asterisk (*) depicts p ≤ 0.001 as compared with control. a.u., absorbance units.

The RTK/GFRs Are Constitutively Activated in NPC2-null Cells

In general, sustained activation of ERK can be achieved through either constitutive activation of the respective upstream kinase(s), persistent phosphatase suppression, or both. We decided to focus on the RTK/GFR constitutive activation as a probable cause for a sustained phosphorylation of ERK for the following reasons. First, the ERK 1/2 is the integral part of the RTK/GFR signaling pathway where it serves as the respective downstream target (70). Second, the RTK/GFR-dependent mechanism has been shown to control fibroblast activation (71–73) as well as scavenger receptor expression (74). Third, our DNA microarray screen of the NPC2-null fibroblasts displayed up-regulated expression of the dual specificity phosphatase 4 (DUSP4) and protein phosphatase 1 (TOPP1/PP1) (data not shown) that are known to efficiently dephosphorylate activated ERK1/2 (75, 76). Therefore, it seemed unlikely that in these settings phosphatase deficiency could be a leading cause for the persistent ERK1/2 activation.

We probed the activation status of the membrane-bound RTK/GFR by using phospho-RTK antibody array (Fig. 5). As in this figure, the absence of NPC2 protein in fibroblasts conferred a constitutive and robust increase in activity of several RTK/GFR including EGF receptor, FGF receptor 2α, ROR2, and Tie-1/2. The relatively high number of constitutively active RTKs in NPC2-null fibroblasts is intriguing and may indicate either their efficient transactivation in response to persistent activation of a single RTK or(and) that NPC2 protein controls a key regulatory step that is common for all activated RTKs. Noteworthy, we also found that several RTKs, one of them being FGF receptor 2α, were constitutively activated in mature human adipocytes after NPC2 gene silencing by siRNA (77). Therefore, it appears that the RTK/GFR ↔ ERK 2 signaling module may represent a regulatory target for NPC2 protein.

FIGURE 5.

Constitutive RTK/GFR activation in NPC2-null fibroblasts. The RTK/GFR activation was probed by human phospho-RTK antibody array using cytosolic fractions of cell lysates isolated from NPC2-null (A) and normal (B) human skin fibroblasts. Signals from particular RTK/GFRs are shown in duplicate and numerically labeled as: 1, EGF receptor; 2, Tie-2; 3, FGF receptor 2α (FGF receptor 2 IIIc); 4, ROR2; 5, Tie-1. C, shown is a semiquantitative analysis of the duplicative signals shown in A and their respective counterparts in B. The images A and B were inverted, and intensities of particular RTK/GFRs were measured and corrected for the background using Adobe Photoshop CS4 Extended software. Data shown are the average (n = 2). a.u., absorbance units.

Activated Fibroblasts from Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Bears NPC2 Deficiency

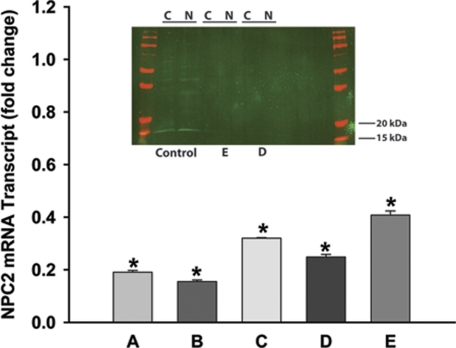

We have already shown (see above) that NPC2 deficiency is sufficient to confer a fibroblast activation phenotype in dermal fibroblasts. Next we reasoned if indeed NPC2 protein participates in regulation of a key process that controls fibroblast activation, then AF in pathologic settings may be NPC2-deficient. To address this question, we chose to study activated SF derived from patients with RA. RA SF, similar to NPC2-null fibroblasts, were shown to maintain their activated and proinflammatory state autonomously, i.e. independently of the other inflammatory cells and cytokines (78). We isolated SF from patients with RA and measured the respective NPC2 mRNA and protein levels by real-time RT-PCR and Western blotting (Fig. 6). All five independent samples studied (A–E) displayed significant, 2.5–5.0-fold reduction in NPC2 mRNA levels as compared with normal skin fibroblasts. Although normal skin fibroblasts demonstrated clear and specific 15–18-kDa NPC2 protein band on the Western blot (Fig. 6), neither of two analyzed independent RA SF samples from which we were able to extract sufficient amount of the total protein (D and E) had detectable levels of NPC2 (Fig. 6, inset). It should be noted that one of those specimens (E) had the highest level of NPC2 mRNA among analyzed samples (Fig. 6), and NPC2 protein bands were visualized using an extremely sensitive near-infrared imaging technique with a low detection limit of <1 pg of protein (see “Experimental Procedures”).

FIGURE 6.

Analysis of NPC2 gene expression in synovial fibroblasts isolated from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The NPC2 mRNA transcript was measured by the real-time RT-PCR in five individual specimens designated A–E. Data normalized to the respective control and shown as the mean ± S.E. (*) depict p ≤ 0.001 as compared with control. Inset, shown is a Western blot analysis of NPC2 protein expression in activated synovial fibroblasts (specimens D and E). Control, normal skin fibroblasts. Cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) protein fractions were analyzed as described under “Experimental Procedures” using the near-infrared LI-COR Odyssey imaging system and its Version 2.0 software. Molecular weight markers are shown in red on both sides of the gel. The amount of the total protein loaded per lane: Control: C, 18 ng, N, 19 ng; E: C, 23 ng, N, 27 ng; D: C, 15 ng, N, 24 ng.

Cholesterol Accumulation Plays No Measurable Role in Either the Induction or the Maintenance of the Activated Fibroblast Phenotype in NPC2-null Cells

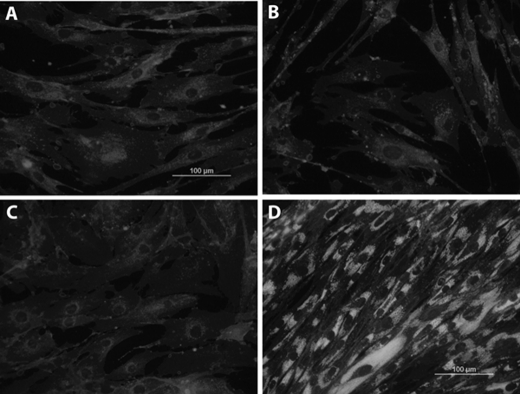

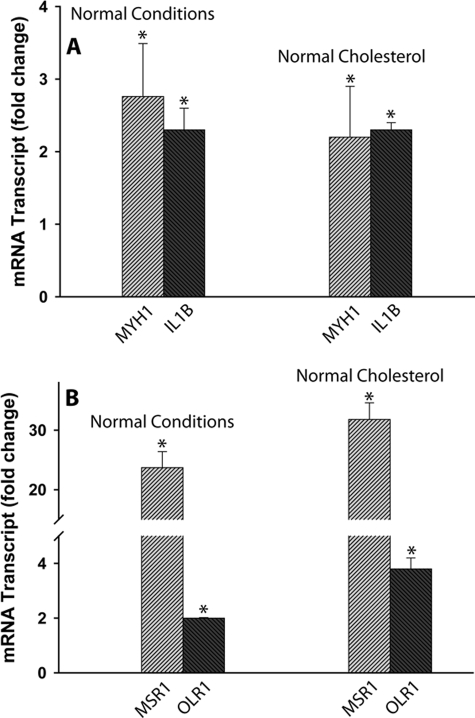

Indeed, 24 h after silencing NPC2 expression in normal human skin fibroblasts by siRNA transfection, these cells displayed no cholesterol accumulation (Fig. 7B) while acquiring the phenotype of activated fibroblasts as demonstrated by their dramatically up-regulated migratory activity (Fig. 2). More importantly, NPC2-deficient human synoviocytes isolated from patients with rheumatoid arthritis displayed normal cholesterol levels and distribution as probed by filipin staining that was undistinguishable from that of normal skin fibroblasts (Fig. 7C). Yet normalization of cholesterol level in NPC2-null human fibroblasts failed to correct their activated phenotype as demonstrated by the unaltered expression of the respective markers that were measured by DNA microarray and real-time RT-PCR (Table 2 and Fig. 8).

FIGURE 7.

Intracellular cholesterol imaging. Cell were stained with the cholesterol probe filipin as previously described (58, 59), and images were taken on the Olympus BX41 microscope equipped with the digital camera controlled by the MagnaFire 2.1 software. A, shown are normal human skin fibroblasts. B, shown are normal human skin fibroblasts 24 h after transfection with NPC2 siRNA. C, shown are human synoviocytes derived from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. D, shown are NPC2-null human skin fibroblasts. All images were taken under the same exposure time (50 ms), and their intensities were adjusted upwards to the identical levels using Adobe Photoshop CS4 Extended Software.

TABLE 2.

Cholesterol normalization in NPC2-null cells failed to correct their activated phenotype; DNA microarray analysis of the activated fibroblasts markers in NPC2-null human skin fibroblasts

| Probe set | Gene name | Symbol | Normal conditions | Normal cholesterola |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeleton proteins | ||||

| 205951_at | Myosin, heavy polypeptide 1, skeletal muscle, adult | MYH1 | Induced | Induced |

| 202274_at | Actin, γ2, smooth muscle, enteric | ACTG2 | Induced | Induced |

| Extracellular matrix proteins | ||||

| 213451_x_at | Tenascin XB | TNXB | Induced | Induced |

| 201787_at | Fibulin 1 | FBLN1 | Induced | Induced |

| 203477_at | Collagen, type XV, α1 | COL15A1 | Induced | Induced |

| 37892_at | Collagen, type XI, α1 | COL11A1 | Induced | Induced |

| 218975_at | Collagen, type V, α3 | COL5A3 | Induced | Induced |

| 213110_s_at | Collagen, type IV, α5 (Alport syndrome) | COL4A5 | Induced | Induced |

| 212940_at | Collagen, type VI, α1 | COL6A1 | ↑ 1.9 | ↑ 1.87 |

| 202311_s_at | Collagen, type I, α1 | COL1A1 | ↑ 1.6 | ↑ 1.26 |

| 213790_at | A disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 12 (meltrin α) | ADAM12 | ↑ 2.3 | ↑ 2.73 |

| 206046_at | A disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 23 | ADAM23 | Induced | Induced |

| 203683_s_at | Vascular endothelial growth factor B | VEGFB | Induced | Induced |

| 205767_at | Epiregulin | EREG | Induced | Induced |

| 206404_at | Fibroblast growth factor 9 (glia-activating factor) | FGF9 | Induced | Induced |

| Scavenger receptors | ||||

| 209555_s_at | CD36 antigen (collagen type I receptor, thrombospondin receptor) | CD36 | Induced | Induced |

| 210004_at | Oxidized low density lipoprotein (lectin-like) receptor 1 | OLR1 (LOX-1) | ↑ 4.53 | ↑ 5.55 |

| 214770_at | Macrophage scavenger receptor 1 | MSR1 (SR-A) | Induced | Induced |

| Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines | ||||

| 39402_at | Interleukin 1, β | IL1B | Induced | Induced |

| 205207_at | Interleukin 6 (interferon, β 2) | IL6 | ↑ 2.54 | ↑ 2.81 |

| 204470_at | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 | CXCL1 (GRO-α) | ↑ 4.04 | ↑ 3.59 |

| 206336_at | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 6 | CXCL6 | Induced | Induced |

| 216598_s_at | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 | CCL2 (MCP-1) | Induced | Induced |

a Cholesterol normalization in NPC2-null human skin fibroblasts (normal cholesterol ∼ 30 μg/mg of protein) was performed by incubating cells in the culture medium supplemented with the lipoprotein deficient serum (LPDS) for 48 h exactly as described previously (58). “Induced” in the Gene expression column identifies genes whose expression was undetectable in the wild type cells and were only present in NPC2-null fibroblasts. See text for experimental details.

FIGURE 8.

Cholesterol normalization in NPC2-null cells failed to correct their activated phenotype; real-time RT-PCR analysis of activated fibroblast markers (A) and scavenger receptors (B) in NPC2-null human skin fibroblasts. Cholesterol normalization (Normal cholesterol, ∼ 30 μg/mg of protein) was performed by incubating cells in the culture medium supplemented with the lipoprotein-deficient serum for 48 h exactly as described previously (58). Data shown are the mean ± S.E. * depicts p ≤ 0.05 as compared with control (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

The significance of the present report is severalfold. First, we identified NPC2 protein as a novel factor that regulates fibroblast activation. This conclusion is based on the following characteristics of NPC2-null dermal fibroblasts that were established in the current studies and were fully consistent with the activated phenotype of these cells; (i) up-regulated expression of specific cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix proteins as well as growth factors, (ii) induction of the innate immune response in non-elicited cells as evidenced by the increased production and secretion of inflammatory cytokines, (iii) up-regulated expression and function of several membrane scavenger receptors, and increased basal (iv) phagocytic and (v) chemotactic activity.

The NPC2-null cells used in the current study were derived from a patient bearing the most common G58T nucleotide mutation, which resulted in the premature termination of the protein translation (55). The phenotype of this particular cell line was identical to that of different NPC2-null (IVS2 + 5G→A) cells (55, 58) and was completely normalized after cell incubation with the recombinant NPC2 protein (53). Yet when these two NPC2-mutant cells were studied alongside the NPC1-mutant cell line bearing the most common I1061T mutation in humans (35), all three cell lines displayed almost identical phenotype (58), which was consistent with the pathology of NPC disease observed in humans and experimental animals (35, 55, 79). Therefore, the NPC2-null cell line that was chosen for this study can be viewed as a correct and representative in vitro model of NPC disease. More importantly, using the siRNA-based silencing of NPC2 gene, we were able to induce activated phenotypes in normal human dermal fibroblasts as well as aortic smooth muscle cells. Therefore, NPC2-deficiency could be considered as sufficient condition for fibroblast activation.

Second, we identified a molecular mechanism through which NPC2 protein exerts its control upon the fibroblast-activated state by demonstrating selective and sustained phosphorylation of the ERK 2 (MAPK1) isoform in NPC2-deficient cells, which fulfills both the necessary and sufficient criteria for the fibroblast activation (32–34, 69). This observation points strongly toward the ERK 1/2 signaling module as a proximal target that is negatively regulated by NPC2 protein. Given that multiple physiologic processes are controlled by sustained ERK activation, including cell transformation (80, 81), proliferation (82), differentiation (83), and inflammation (84), we may predict a very broad and important NPC2 regulatory function in the maintenance of cell and tissue phenotypic stability. As a consequence, impairment of NPC2 function may be associated with important human diseases including cancer, tissue fibrotic disorders, atherosclerosis, and RA.

This conclusion is supported by the third important aspect of our present study where we demonstrated that SF derived from patients with RA were indeed NPC2-deficient with no detectable NPC protein level as probed by Western blotting. RA is a systemic inflammatory disorder affecting 0.5–2% of Western population (16, 85). It is characterized primarily by synovial hyperplasia and inflammation that eventually lead to joint destruction and deformity, resulting in physical disability. Patients with RA have excessive mortality which is increased approximately ∼2.0-fold above controls (86) and is mostly attributable to the accelerated development of coronary heart disease (87). This results in a reduction in the average lifespan of RA patients by as much as 15 years (88).

Therefore, it would be of great importance to identify a novel therapeutic target(s) affecting both RA and coronary heart disease. Activated synovial and adventitial fibroblasts have been recently proposed to be a central event in the initiation and development of RA (16, 89) as well as the atherosclerotic arterial vessel wall remodeling (62, 90, 91). Intriguingly, deficiency in the product of the first gene in NPC-disease, NPC1, which may function simultaneously or sequentially in the NPC2 pathway, has been shown to accelerate development of atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice with a pronounced adventitial inflammatory component (92). It should be noted that although previous literature on NPC has highlighted abnormal lipid accumulation and work on NPC1 and NPC2 has focused on their potential role in cholesterol metabolism and abnormal lipid accumulation, we have no evidence that fibroblast activation is dependent on cholesterol accumulation in NPC2 deficient cells. Therefore, our data are in line with that of others who demonstrated a novel function for NPC2 protein in regulation of hematopoiesis (53) and immunity (54) that were independent of NPC2 cholesterol binding ability. In summary, our studies highlight NPC2 protein as a potentially novel multifaceted therapeutic target for the treatment of RA and its associated cardiovascular diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dan Ory (Washington University in St. Louis) for providing the NPC2-null human fibroblasts.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1AR049010 (to L. J. C.). This work was also supported by American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant SDG 023017N, the University of Cincinnati Millennium Fund, and the Department of Internal Medicine Start-Up Fund (to A. F.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- AF

- activated fibroblasts

- SMC

- smooth muscle cells

- NPC

- Niemann-Pick Type C

- RTK

- receptor-tyrosine kinase

- GFR

- growth factor receptor

- SF

- synovial fibroblasts.

REFERENCES

- 1. Takahashi K., Yamanaka S. (2006) Cell 126, 663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Takahashi K., Tanabe K., Ohnuki M., Narita M., Ichisaka T., Tomoda K., Yamanaka S. (2007) Cell 131, 861–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vierbuchen T., Ostermeier A., Pang Z. P., Kokubu Y., Südhof T. C., Wernig M. (2010) Nature 463, 1035–1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haniffa M. A., Collin M. P., Buckley C. D., Dazzi F. (2009) Haematologica 94, 258–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lysy P. A., Smets F., Sibille C., Najimi M., Sokal E. M. (2007) Hepatology 46, 1574–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Junker J. P., Sommar P., Skog M., Johnson H., Kratz G. (2010) Cells Tissues Organs 191, 105–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hinz B. (2007) J. Invest. Dermatol. 127, 526–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McAnulty R. J. (2007) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 666–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Corre J., Barreau C., Cousin B., Chavoin J. P., Caton D., Fournial G., Penicaud L., Casteilla L., Laharrague P. (2006) J. Cell. Physiol. 208, 282–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sen M., Lauterbach K., El-Gabalawy H., Firestein G. S., Corr M., Carson D. A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 2791–2796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li X., Makarov S. S. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 17432–17437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scotton C. J., Chambers R. C. (2007) Chest 132, 1311–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bataller R., Brenner D. A. (2005) J. Clin. Invest. 115, 209–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van den Borne S. W., Diez J., Blankesteijn W. M., Verjans J., Hofstra L., Narula J. (2010) Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 7, 30–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kalluri R., Zeisberg M. (2006) Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 392–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huber L. C., Distler O., Tarner I., Gay R. E., Gay S., Pap T. (2006) Rheumatology 45, 669–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stenmark K. R., Davie N., Frid M., Gerasimovskaya E., Das M. (2006) Physiology 21, 134–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wilcox J. N., Scott N. A. (1996) Int. J. Cardiol. 54, S21–S35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilcox J. N., Okamoto E. I., Nakahara K. I., Vinten-Johansen J. (2001) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 947, 68–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dzau V. J., Braun-Dullaeus R. C., Sedding D. G. (2002) Nat. Med. 8, 1249–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Camelliti P., Borg T. K., Kohl P. (2005) Cardiovasc. Res. 65, 40–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Desmoulière A., Chaponnier C., Gabbiani G. (2005) Wound Repair Regen. 13, 7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De Wever O., Demetter P., Mareel M., Bracke M. (2008) Int. J. Cancer 123, 2229–2238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Manabe I., Shindo T., Nagai R. (2002) Circ. Res. 91, 1103–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chintalgattu V., Nair D. M., Katwa L. C. (2003) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 35, 277–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ebihara N., Yamagami S., Chen L., Tokura T., Iwatsu M., Ushio H., Murakami A. (2007) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48, 3069–3076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Erwig L. P., McPhilips K. A., Wynes M. W., Ivetic A., Ridley A. J., Henson P. M. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 12825–12830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nagao S., Nemoto H., Suzuki M., Satoh N., Iijima S. (1986) J. Cutan. Pathol. 13, 261–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chung S. W., Liu X., Macias A. A., Baron R. M., Perrella M. A. (2008) J. Clin. Invest. 118, 239–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gressner O. A., Rizk M. S., Kovalenko E., Weiskirchen R., Gressner A. M. (2008) J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 23, 1024–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Derynck R., Akhurst R. J. (2007) Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 1000–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schramek H., Feifel E., Healy E., Pollack V. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 11426–11433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schramek H., Feifel E., Marschitz I., Golochtchapova N., Gstraunthaler G., Montesano R. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 285, C652–C661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yang M., Huang H., Li J., Li D., Wang H. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 1920–1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vanier M. T., Millat G. (2003) Clin. Genet. 64, 269–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wojtanik K. M., Liscum L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14850–14856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Millard E. E., Gale S. E., Dudley N., Zhang J., Schaffer J. E., Ory D. S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28581–28590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chang T. Y., Reid P. C., Sugii S., Ohgami N., Cruz J. C., Chang C. C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 20917–20920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lloyd-Evans E., Morgan A. J., He X., Smith D. A., Elliot-Smith E., Sillence D. J., Churchill G. C., Schuchman E. H., Galione A., Platt F. M. (2008) Nat. Med. 14, 1247–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lloyd-Evans E., Platt F. M. (2010) Traffic 11, 419–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dormeyer W., van Hoof D., Braam S. R., Heck A. J., Mummery C. L., Krijgsveld J. (2008) J. Proteome Res. 7, 2936–2951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Srikanth K. N., Kulkarni A., Davies A. M., Sumathi V. P., Grimer R. J. (2005) Sarcoma 9, 33–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yanagimoto C., Harada M., Kumemura H., Koga H., Kawaguchi T., Terada K., Hanada S., Taniguchi E., Koizumi Y., Koyota S., Ninomiya H., Ueno T., Sugiyama T., Sata M. (2009) Exp. Cell Res. 315, 119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Davies J. P., Chen F. W., Ioannou Y. A. (2000) Science 290, 2295–2298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Goldman S. D., Krise J. P. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 4983–4994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kaufmann A. M., Krise J. P. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 24584–24593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Okamura N., Kiuchi S., Tamba M., Kashima T., Hiramoto S., Baba T., Dacheux F., Dacheux J. L., Sugita Y., Jin Y. Z. (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1438, 377–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Naureckiene S., Sleat D. E., Lackland H., Fensom A., Vanier M. T., Wattiaux R., Jadot M., Lobel P. (2000) Science 290, 2298–2301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Friedland N., Liou H. L., Lobel P., Stock A. M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2512–2517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Klein A., Amigo L., Retamal M. J., Morales M. G., Miquel J. F., Rigotti A., Zanlungo S. (2006) Hepatology 43, 126–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ko D. C., Binkley J., Sidow A., Scott M. P. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2518–2525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Storch J., Xu Z. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791, 671–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Heo K., Jariwala U., Woo J., Zhan Y., Burke K. A., Zhu L., Anderson W. F., Zhao Y. (2006) Stem Cells 24, 1549–1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schrantz N., Sagiv Y., Liu Y., Savage P. B., Bendelac A., Teyton L. (2007) J. Exp. Med. 204, 841–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Millat G., Chikh K., Naureckiene S., Sleat D. E., Fensom A. H., Higaki K., Elleder M., Lobel P., Vanier M. T. (2001) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69, 1013–1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bjurulf B., Spetalen S., Erichsen A., Vanier M. T., Strøm E. H., Strømme P. (2008) Med. Sci. Monit. 14, CS71–CS75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Verot L., Chikh K., Freydière E., Honoré R., Vanier M. T., Millat G. (2007) Clin. Genet. 71, 320–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Frolov A., Zielinski S. E., Crowley J. R., Dudley-Rucker N., Schaffer J. E., Ory D. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25517–25525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Frolov A., Srivastava K., Daphna-Iken D., Traub L. M., Schaffer J. E., Ory D. S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 46414–46421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Del Vecchio M. A., Georgescu H. I., McCormack J. E., Robbins P. D., Evans C. H. (2001) Arthritis Res. 3, 259–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yamasaki S., Nakashima T., Kawakami A., Miyashita T., Ida H., Migita K., Nakata K., Eguchi K. (2002) Clin. Exp. Immunol. 129, 379–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Faggin E., Puato M., Zardo L., Franch R., Millino C., Sarinella F., Pauletto P., Sartore S., Chiavegato A. (1999) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19, 1393–1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gillibert-Duplantier J., Neaud V., Blanc J. F., Bioulac-Sage P., Rosenbaum J. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 293, G128–G136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kinnman N., Hultcrantz R., Barbu V., Rey C., Wendum D., Poupon R., Housset C. (2000) Lab. Invest. 80, 697–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Karouzakis E., Gay R. E., Gay S., Neidhart M. (2009) Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 5, 266–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Santucci M., Borgognoni L., Reali U. M., Gabbiani G. (2001) Virchows Arch. 438, 457–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hu C., Dandapat A., Sun L., Khan J. A., Liu Y., Hermonat P. L., Mehta J. L. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 10226–10231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Okamura D. M., Pennathur S., Pasichnyk K., López-Guisa J. M., Collins S., Febbraio M., Heinecke J., Eddy A. A. (2009) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20, 495–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schramek H., Schumacher M., Wilflingseder D., Oberleithner H., Pfaller W. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. 272, C383–C391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Schlessinger J. (2004) Science 306, 1506–1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hobbs R. M., Watt F. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 19798–19807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Le P. T., Lazorick S., Whichard L. P., Haynes B. F., Singer K. H. (1991) J. Exp. Med. 174, 1147–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Grotendorst G. R., Rahmanie H., Duncan M. R. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 469–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Gong Q., Pitas R. E. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 21672–21678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Liu Y., Shepherd E. G., Nelin L. D. (2007) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 202–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Gardai S. J., Whitlock B. B., Xiao Y. Q., Bratton D. B., Henson P. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 44695–44703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Csepeggi C., Jiang M., Frolov A. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 30347–30354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ospelt C., Kyburz D., Pierer M., Seibl R., Kurowska M., Distler O., Neidhart M., Muller-Ladner U., Pap T., Gay R. E., Gay S. (2004) Ann. Rheum. Dis. 63, ii90–ii91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sleat D. E., Wiseman J. A., El-Banna M., Price S. M., Verot L., Shen M. M., Tint G. S., Vanier M. T., Walkley S. U., Lobel P. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 5886–5891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lopez-Bergami P., Huang C., Goydos J. S., Yip D., Bar-Eli M., Herlyn M., Smalley K. S., Mahale A., Eroshkin A., Aaronson S., Ronai Z. (2007) Cancer Cell 11, 447–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Tashiro K., Tsunematsu T., Okubo H., Ohta T., Sano E., Yamauchi E., Taniguchi H., Konishi H. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 20206–20214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Stork P. J., Schmitt J. M. (2002) Trends Cell Biol. 12, 258–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Eriksson M., Taskinen M., Leppä S. (2007) J. Cell. Physiol. 210, 538–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Na S. Y., Patra A., Scheuring Y., Marx A., Tolaini M., Kioussis D., Hemmings B. A., Hemmings B., Hünig T., Bommhardt U. (2003) J. Immunol. 171, 1285–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Haque S., Mirjafari H., Bruce I. N. (2008) Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 19, 338–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Naz S. M., Symmons D. P. (2007) Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 21, 871–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Van Doornum S., McColl G., Wicks I. P. (2002) Arthritis Rheum. 46, 862–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Gabriel S. E. (2008) Am. J. Med. 121, S9–S14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Mor A., Abramson S. B., Pillinger M. H. (2005) Clin. Immunol. 115, 118–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Herrmann J., Samee S., Chade A., Rodriguez, Porcel M., Lerman L. O., Lerman A. (2005) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 447–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sartore S., Chiavegato A., Faggin E., Franch R., Puato M., Ausoni S., Pauletto P. (2001) Circ. Res. 89, 1111–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Welch C. L., Sun Y., Arey B. J., Lemaitre V., Sharma N., Ishibashi M., Sayers S., Li R., Gorelik A., Pleskac N., Collins-Fletcher K., Yasuda Y., Bromme D., D'Armiento J. M., Ogletree M. L., Tall A. R. (2007) Circulation 116, 2444–2452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.