Abstract

HIV-1 Nef is a multifunctional protein that exerts its activities through interactions with multiple cellular partners. Nef uses different domains and mechanisms to exert its functions including cell surface down-modulation of CD4 and MHC-I receptors and activation of the serine/threonine kinase PAK-2. We inserted tags at the C-terminus and proximal to the N-terminus of Nef and the effects on Nef’s structure/function relationships were examined. We discovered significant defects in MHC-I down-modulation with the insertion of HA/FLAG tags at either region. We also found impaired PAK-2 activation with a C-terminal fusion with GFP. Interestingly, Nef-GFP and Nef-GH7 induced MHC-I down-modulation, suggesting that the negative charge of the HA/FLAG tag could contribute to the observed defect. Together, these observations highlight elements of Nef’s functional complexity and demonstrate previously unsuspected structural requirements for PAK-2 activation and MHC-1 down-modulation in Nef’s flexible N and C-terminal regions.

Keywords: HIV-1, Nef, structure-function, peptide tags, GFP, MHC-I down-modulation, CD4 down-modulation, PAK-2 activation

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Nef is a 27–29 kDa accessory protein expressed at high levels early and throughout the viral life cycle (Wei et al., 2003). Nef is functionally complex (Arold and Baur, 2001; Foster et al., 2001; Geyer, Fackler, and Peterlin, 2001; O’Neill et al., 2006) and is a major determinant of viral pathogenicity (Kestler et al., 1991). Having no known enzymatic activity, Nef instead likely functions as a molecular adaptor, intercepting cellular signaling pathways via protein-protein interactions (Arold and Baur, 2001; Geyer, Fackler, and Peterlin, 2001; Roeth and Collins, 2006). Alleles of Nef have been identified that are singly defective in three intensely studied in vitro functions of Nef: MHC-1 downregulation, CD4 downregulation and PAK-2 activation (Carl et al., 2001; Foster et al., 2001) which is consistent with Nef executing each of its functions via interactions with distinct cellular factors or complexes. Identification of the host cell proteins that interact with Nef and relating different Nef complexes to Nef function is a major area of investigation (Janardhan et al., 2004)

The longest studied function of Nef is down-regulation of cell surface CD4 (Garcia and Miller, 1991; Guy et al., 1987) which is predicted to prevent super-infection of the host cell and minimize the inhibitory effect of high CD4 levels on virus production (Benson et al., 1993; Lama, Mangasarian, and Trono, 1999; Ross, Oran, and Cullen, 1999). Nef is reported to act as a connector between the cytoplasmic tail of CD4 and the cell’s endocytotic machinery (Bentham, Mazaleyrat, and Harris, 2003; Mangasarian et al., 1997). Host cell binding partners for Nef potentially relevant for this function include adaptor complexes (Bresnahan, Yonemoto, and Greene, 1999; Craig, Pandori, and Guatelli, 1998; Greenberg et al., 1998; Greenberg et al., 1997), a subunit of the vacuolar ATPase complex (Geyer et al., 2002; Lu et al., 1998), and the coatomer protein, β-COP (Benichou et al., 1994; Janvier et al., 2001).

Another conserved function of Nef is down-modulation of cell surface major histocompatibility class I (MHC-I) (Schwartz et al., 1996) which reduces exposure of viral antigens to cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (Collins et al., 1998). While the mechanism by which Nef effects this function is controversial, several functional domains of Nef are reported to be required, including an amphipathic α-helix (R17ERM20RRAEPA26), an acidic region (E62–65) and a polyproline helix (P69/72/75/78) (Akari et al., 2000; Greenberg, Iafrate, and Skowronski, 1998; Mangasarian et al., 1999). The α-helix, acidic region and polyproline helix may be involved in the direct binding of Nef to the cytoplasmic tail of MHC-I (Williams et al., 2005), and the acidic region is postulated to also mediate an association with PACS-1 (Blagoveshchenskaya et al., 2002; Piguet et al., 2000).

A third function of Nef is the binding and activation of the serine/threonine kinase p21-activated kinase 2 (PAK-2). The mechanism of activation is not yet resolved, but is thought to involve a multi-protein complex of Nef, PAK-2, β-PIX and other unidentified proteins (Arora et al., 2000; Brown et al., 1999; Renkema, Manninen, and Saksela, 2001).

HIV-1 Nef has a genetically diverse and structurally flexible N-terminal region of ~70 residues followed by a relatively well-conserved core domain of ~130 residues and a C-terminal tail of five amino acids (Arold and Baur, 2001). In contrast to the long structured C-terminus of SIVmac239 Nef, the C-terminal ends of HIV Nefs are short and flexible (Hochrein et al., 2006). The core domain is the only part of Nef that adopts a stable tertiary fold, and its structure has been solved by X-ray crystallography (Arold et al., 1997) and NMR (Arold et al., 2000). Solving the structure of full-length Nef has so far proved difficult (Arold and Baur, 2001; Hochrein et al., 2006).

Functional roles of the N-terminal and C-terminal flexible regions of HIV-1 Nef are not known. The N-terminal flexible amino acids 21–34 in HIV-1 Nef may merely serve as a linker between the two short alpha helices (amino acids 15–20 and 35–41)(Geyer et al., 1999). The C-terminal ~25 amino acid truncation of HIV-1 Nefs relative to SIVmac239 Nef is striking since the C-terminus of SIVmac239 Nef is required for protein stability (Garcia and Foster, 1996). If these regions have no specific function in HIV-1 Nef, then they would be good candidates for epitope tag placement. Therefore, we attached peptide tags which varied in length and overall charge to the C-terminus or proximal to the N-terminus of Nef. Attachment/insertion of the peptide tags at these locations would not be predicted to alter the structure of the Nef core domain or prevent myristoylation of Nef, but our results demonstrate that alterations at opposite sides of the molecule can result in strongly impaired MHC-I down-modulation. Furthermore, fusion of GFP to the C-terminal end of Nef yields a Nef fusion protein defective in PAK-2 activation, and the severity of the defect is isolate-dependent. These results demonstrate unexpected structural requirements for Nef function at the flexible N- and C-terminal regions.

RESULTS

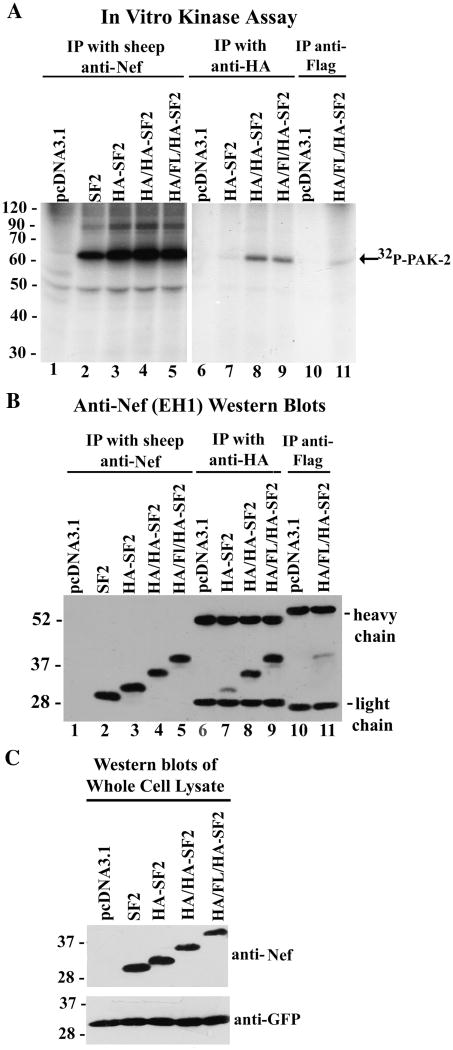

To investigate possible effects of a C-terminal HA/FLAG (HF) tag on Nef function, constructs expressing HIV-1 SF2 or NA7 Nefs or Nefs tagged at the C-terminus (SF2, SF2-HF, NA7, NA7-HF)(Fig. 1A) were transfected into 293T cells and cellular lysates were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal anti-Nef antibodies or monoclonal anti-HA or anti-FLAG antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by in vitro kinase assay to examine PAK-2 binding and activation by Nef (Sawai et al., 1994). As depicted in Fig. 2A, a robust PAK-2 activation signal was detected with SF2, SF2-HF, NA7 and NA7-HF Nefs when cellular lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Nef antibodies (lanes 2- 5). Unexpectedly, little PAK-2 activation was detected when the same SF2-HF or NA7-HF Nefs were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA (lanes 7, 8) or anti-FLAG antibodies (lanes 10, 11). Although these results indicate that the C-terminal HA/FLAG tag does not interfere with PAK-2 activation by Nef (compare lane 2 to lane 3 and lane 4 to lane 5), PAK-2 activity was not co-immunoprecipitated with Nef using anti-tag antibodies. Immunoprecipitations of tagged Nefs with tag-specific antibodies were also analyzed by Western blot to determine if the bulk of Nef was refractory to immunoprecipitation or only the fraction of Nef bound to PAK-2 (Fig. 2B). Tagged Nefs were efficiently immunoprecipitated with polyclonal anti-Nef antibodies (lanes 3, 5), anti-HA antibodies (lanes 7, 8) and anti-FLAG antibodies (lanes 10, 11). It has been previously reported that the minor fraction of Nef complexed to activated PAK-2 is not detectable by Western blot or metabolic labeling (Arora et al., 2000; Renkema, Manninen, and Saksela, 2001; Sawai et al., 1994). Therefore, the majority of Nef-HF can be immunoprecipitated with anti-tag antibodies, but PAK-2 activity is not co-immunoprecipitated, suggesting that the C-terminal tags may not form stable complexes with anti-tag antibodies when Nef is bound to activated PAK-2. Alternatively, binding by anti-tag antibodies may disrupt the Nef/PAK-2 activation complex during immunoprecipitation of cell extracts, sterically hinder the Nef/PAK-2 interaction or interfere with PAK-2 autophosphorylation in the in vitro kinase assay.

FIG. 1. Diagram of Nefs Modified with Exogenous Sequences.

(A) SF2-HF or NA7-HF Nefs; (B) SF2-GFP or NA7-GFP Nefs; (C) SF2-GH7 Nef; (D) HA-SF2, HA/HA-SF2 or HA/FL/HA-SF2 Nefs. The dark line represents the coding sequence of HIV-1 SF2 or NA7 Nef.

FIG. 2. Preferential co-immunoprecipitation of activated PAK-2 with C-terminal HA/FLAG (HF) tagged SF2 and NA7 Nefs with anti-Nef antibodies.

Plasmids expressing SF2 or NA7 Nefs or Nefs tagged at the C-terminus with HA/FLAG were transfected into 293T cells. Cellular lysates were immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies and PAK-2 binding and activation was assayed by in vitro kinase assay (A) or immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot with the mouse monoclonal anti-Nef antibody (EH1) to monitor the efficiency of immunoprecipitation (B). The positions of the heavy and light chains of the mouse antibodies used for immunoprecipitation are indicated to the right of the blots. Protein expression levels and transfection efficiency were assayed by Western blot of whole cell lysates using anti-Nef or anti-GFP antibodies (C).

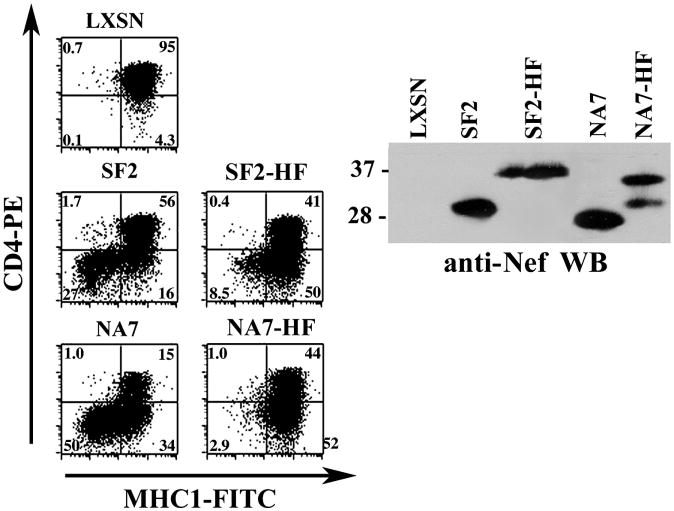

Next, we evaluated the effect of the HA/FLAG C-terminal tag on cell surface CD4 and MHC-I down-modulation. Transduced CEM cells expressing SF2, SF2-HF, NA7 or NA7-HF Nefs were analyzed by two-color flow cytometry for cell surface CD4 and MHC-I. As shown in Fig. 3, both SF2-HF and NA7-HF Nefs induced CD4 down-modulation. However, a significant defect in MHC-I down-modulation was observed with both SF2-HF and NA7-HF (the levels of MHC-I down-modulation for SF2-HF and NA7-HF were 8 and 3% respectively whereas the levels for SF2 and NA7 were 28 and 50% respectively). Even though we noted reduced steady state levels of NA7-HF compared to NA7 that could partially explain the MHC-I defect for this isolate, the defect observed with SF2-HF appears to result from the presence of the HF tag.

FIG. 3. CD4 and MHC-I down-modulation with C-terminal HA/FLAG (HF) tagged SF2 and NA7 Nefs.

CEM cells expressing SF2, SF2-HF, NA7 or NA7-HF Nefs were analyzed for down-modulation of cell-surface MHC-I and CD4 using two-color flow cytometry (left panels). Nef expression in the transduced CEM cells was confirmed by Western blotting of cellular lysates with anti-Nef antibodies (right panel).

Since tagging Nef with short amino acid sequences at the C-terminus resulted in functional defects in Nef, we were interested in what effect a relatively large tag would have on Nef function. Therefore, we fused GFP to the C-terminus of Nef (Fig. 1B). To determine whether Nef-GFP would co-immunoprecipitate with active PAK-2, constructs expressing SF2, SF2-GFP, NA7 and NA7-GFP Nef were transfected into 293T cells, cellular lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Nef antibodies and analyzed by in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 4A). Our results indicated that fusing GFP to the C-terminal end of Nef results in a reduction in the level of activated PAK-2 associated with Nef (compare lane 2 to lane 3 and lane 4 to lane 5). The impact of the GFP fusion on PAK-2 binding/activation was found to be different for the two Nefs used. SF2-GFP has 33 +/− 5% (n=4) of the level of PAK-2 activation observed with wild type SF2 (compare lanes 2, 3). NA7-GFP was found to be essentially nonfunctional for PAK-2 activation (lane 5, n=4). The defect in PAK-2 activation is not due to an inability of anti-Nef antibodies to recognize the Nef-GFP fusion proteins, since analysis of anti-Nef immunoprecipitates indicated that the bulk of Nef was efficiently immunoprecipitated (Fig. 4A, lower panel). The defect in PAK-2 activation may be due to the much larger size of the GFP molecule compared to the HA/FLAG tag.

FIG. 4. Functional Analysis of C-terminal Nef-GFP fusion proteins.

(A) Empty vector (pCGCG) or plasmids expressing SF2, SF2-GFP, NA7, and NA7-GFP were transfected into 293T cells. Cellular lysates were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal anti-Nef antibodies and PAK-2 binding and activation was assayed by in vitro kinase assay (upper left panel). The efficiency of immunoprecipitation of the different Nefs using polyclonal anti-Nef antibodies was determined by Western blot of immunoprecipitates (lower left panel). Protein expression levels and transfection efficiency were assayed by Western blot of whole cell lysates using mouse anti-Nef and anti-GFP antibodies (right upper and lower panels). Note that the pCGCG vector constitutively expresses GFP (30 kD). (B) CEM cells transduced with LXSN or LnefSN (expressing Nef or Nef-GFP fusion proteins) were analyzed for down-modulation of cell-surface MHC-I and CD4 using two-color flow cytometry. Nef expression levels in the transduced CEM cells were determined by Western blotting of cellular lysates with anti-Nef antibodies.

To assay cell surface receptor down-modulation, CEM cells were transduced with vectors expressing Nef or Nef-GFP fusion proteins (Fig. 4B). Cells were analyzed for down-modulation of CD4 or MHC-I as well as GFP expression, to monitor down-regulation in the transduced cell populations. Our results indicate that SF2-GFP and NA7-GFP down-modulated cell surface CD4 and MHC-I at comparable levels to SF2 and NA7 respectively.

We considered the possibility that the highly negative charge of the HA/FLAG tag (8 D, 2 K, 1 R) may contribute to the defect observed with the ability of Nef-HF to down-modulate MHC-1, since the much larger (249 amino acid) Nef-GFP fusion protein was substantially more active than Nef-HF in this particular function. Thus a tag devoid of negative charge GH7 (a tag with one glycine and seven histidines) was added to the C-terminus of SF2 Nef (Fig. 1C) and analyzed for the three different Nef functions. To analyze PAK-2 activation, 293T cells were transfected with constructs expressing either SF2 or SF2-GH7, cellular lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Nef antibodies and analyzed by in vitro kinase assay. Our results indicate that SF2-GH7, like SF2-HF and NA7-HF, was fully functional for PAK-2 activation (Fig. 2A and Fig. 5A) suggesting that the impaired PAK-2 activation with Nef-GFP was due the large size of the GFP fusion protein. Similar results were obtained with NA7-GH7 (data not shown). Interestingly, SF2-GH7 modestly increased PAK-2 activation compared to SF2 (p = 0.03). To analyze cell surface receptor down-modulation, CEM cells were transduced with retroviral vectors expressing either SF2 or SF2-GH7 and cell-surface down-modulation of both CD4 and MHC-I was analyzed by two-color flow cytometry. SF2-GH7 was functional for both CD4 and MHC-I down-modulation (45% and 44% respectively)(Fig. 5). Similar results were obtained with NA7-GH7 (data not shown). These results demonstrate that the deleterious effect of a C-terminal tag on Nef does not correlate only to the length of the tag (a relatively short and a long tag (GH7 and GFP) modestly altered MHC-1 down-modulation whereas an intermediate length tag (HF) resulted in a severe defect). Rather, these data suggest that the excess negative charge at the C-terminus of Nef with the HF tag could contribute to the disruption in MHC-I down-modulation.

FIG. 5. Functional Analysis of Nef containing a positive amino acid C-terminal tag (SF2 Nef-GH7).

(A) Empty vector (pcDNA3.1) or plasmids expressing SF2 or SF2-GH7 were transfected into 293T cells. Cellular lysates were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal anti-Nef antibodies and PAK-2 binding and activation was assayed by in vitro kinase assay (upper left panel). The efficiency of immunoprecipitation of the Nefs using polyclonal anti-Nef antibodies was determined by Western blot of separate immunoprecipitates (lower left panel). Protein expression levels and transfection efficiency were assayed by Western blot of the whole cell lysate using mouse anti-Nef and anti-GFP antibodies (right upper and lower panels respectively). (B) CEM cells expressing SF2 or SF2-GH7 were analyzed for down-modulation of cell-surface MHC-I and CD4 using two-color flow cytometry. Nef expression levels in the transduced CEM cells were determined by Western blotting of cellular lysates with anti-Nef antibodies.

Next, we were interested in analyzing the structural/functional effects of insertion of exogenous sequences within the N-terminal region of Nef. The N-terminus of Nef cannot be modified since N-terminal myristoylation and membrane insertion of Nef are required for all known Nef activities except for the activation of Hck (Aiken and Trono, 1995; Briggs et al., 2001; Chowers et al., 1994; Wiskerchen and Cheng-Mayer, 1996). Nefs are highly polymorphic with regard to length in the 17–26 amino acid region, and most of the variability is accounted for by duplications of 2–10 amino acids (O’Neill et al., 2006). There is a four amino acid duplication (RAEP) from amino acid 22 to 25 in SF2 Nef but removal of these four amino acids has no significant effect on PAK-2 activation, CD4 down-modulation and enhancement of viral infectivity (O’Neill et al., 2006). Importantly, these duplications do not disrupt the function of the amphipathic alpha helix to their N-terminal side (R17ERM20RRAEPA26) in MHC-I down-modulation (O’Neill et al., 2006). Other regions of length polymorphism exist in Nef but these consist of less common short deletions (O’Neill et al., 2006). Therefore, the four amino acid duplication in SF2 Nef was removed and replaced with tag sequences, which include HA, HA/HA, and HA/FLAG/HA (Fig. 1D).

To examine PAK-2 activation using these internally tagged Nefs, constructs expressing SF2, HA-SF2, HA/HA-SF2 and HA/FLAG/HA-SF2 Nefs were transfected into 293T cells. Cellular lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Nef, anti-HA or anti-FLAG antibodies and immunoprecipitates were analyzed for PAK-2 activation by in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 6A). A strong PAK-2 activation signal was observed with all four Nefs when lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Nef antibodies (Fig. 6A, lanes 2–5). However, compared to the anti-Nef immunoprecipitations, less than 10% of activated PAK-2 was co-immunoprecipitated with HA, HA/HA or HA/FLAG/HA tagged SF2 Nefs using anti-HA antibodies (Fig. 6A, lanes 7–9) or anti-FLAG antibodies (lane 11). To determine if the bulk Nef or just the Nef/PAK-2 complex was refractory to immunoprecipitation with anti-tag antibodies, anti-Nef, anti-HA or anti-FLAG immunoprecipitates were also analyzed by Western blot (Fig. 6B). Our results indicate that all four Nefs were efficiently immunoprecipitated with anti-Nef antibodies (Fig. 6B, lanes 2–5), and that the HA/HA and HA/FLAG/HA internally tagged Nefs were efficiently immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies (lanes 8–9). Interestingly, Nef with a single HA tag was poorly immunoprecipitated by anti-HA antibodies (lane 7). Furthermore, we were surprised to find that the FLAG epitope of HA/FLAG/HA-Nef was poorly recognized by anti-FLAG antibodies (lane 11), in contrast to the C-terminal HA/FLAG tag (Fig. 2B, lanes 10–11). Altogether, these results demonstrate that insertion of the HA, HA/HA or HA/FLAG/HA tags at a position proximal to the N-terminus of Nef does not inhibit PAK-2 activation by Nef. However, activated PAK-2 is not co-immunoprecipitated with the internally tagged Nefs using anti-tag antibodies. The HA/HA and HA/FLAG/HA tags may be sterically hindered in the Nef/PAK-2 complex and not accessible to anti-tag antibodies or the anti-tag antibodies may interfere with PAK-2 autophosphorylation in the in vitro kinase assay. However, bulk Nef is refractory to anti-HA immunoprecipitation of the single HA-tagged Nef as well as anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation of the HA/FLAG/HA tagged Nef.

FIG. 6. Co-immunoprecipitation of activated PAK-2 with Nefs containing HA, HA/HA or HA/FLAG/HA tags inserted at position 24 with anti-Nef and anti-tag antibodies.

Empty vector (pcDNA3.1) or plasmids expressing SF2 or SF2 containing the internally inserted tags HA, HA/HA or HA/FLAG/HA were transfected into 293T cells. Cellular lysates were immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies and PAK-2 binding and activation was assayed by in vitro kinase assay (A), or anti-tag immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot with mouse anti-Nef antibodies (EH1) to monitor the efficiency of immunoprecipitation (B). The positions of the heavy and light chains of the mouse antibodies used for immunoprecipitation are indicated to the right of the blots. Protein expression levels and transfection efficiency were assayed by Western blot of the whole cell lysate using mouse anti-Nef and anti-GFP antibodies (C).

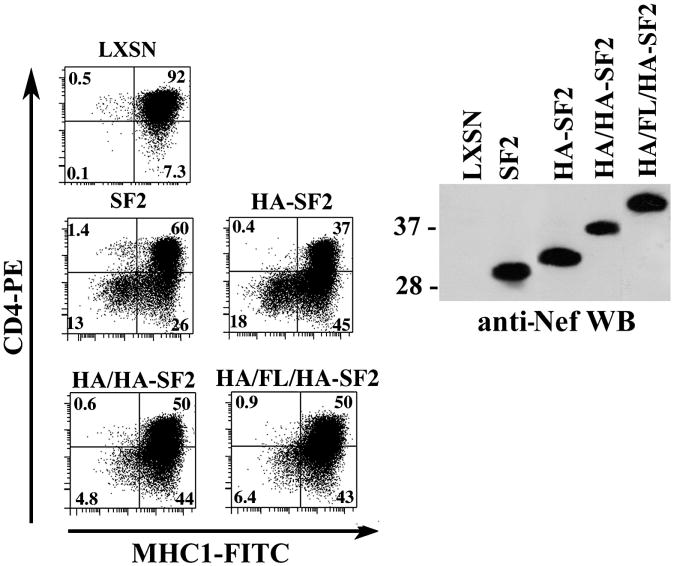

We then evaluated the effect of the N-terminal proximal internal tags on CD4 and MHC-I down-modulation in transduced CEM cells. As shown in Fig. 7, SF2, HA-SF2, HA/HA-SF2 and HA/FLAG/HA-SF2 demonstrated similar levels of CD4 down-modulation. In contrast, HA/HA-SF2 and HA/FLAG/HA-SF2, but not HA-SF2, demonstrated significant defects in MHC-I down-modulation compared to SF2 Nef.

FIG. 7. CD4 and MHC-I down-modulation with Nefs containing HA, HA/HA or HA/FLAG/HA tags inserted at position 24.

CEM cells transduced with LXSN or LnefSN (expressing SF2 or SF2 Nefs with internal tags) were analyzed for down-modulation of cell-surface MHC-I and CD4 using two-color flow cytometry (left panel). Nef expression levels in the transduced CEM cells were determined by Western blotting of cellular lysates with anti-Nef antibodies (right panel).

DISCUSSION

C-terminal addition of HA and FLAG tags to SF2 or NA7 Nefs resulted in proteins that were functional for PAK-2 activation but that did not co-immunoprecipitate active PAK-2 with anti-tag antibodies, even though the bulk population of Nef was immunoprecipitated. These results may explain the reason PAK-2 and other proteins such as β-PIX (Brown et al., 1999; Renkema, Manninen, and Saksela, 2001) were not detected in the large-scale immunochemical purification of NA7-HF that did identify DOCK2 and ELMO1 as Nef binding proteins (Janardhan et al., 2004). A simple explanation is that the components of the Nef/PAK-2 complex sterically hinder the interaction of the HA/FLAG tag with anti-HA or anti-FLAG antibodies. That cellular proteins bind to Nef in the C-terminal region is consistent with mutational data demonstrating the functional significance of F191 for PAK-2 activation (O’Neill et al., 2006). However, another possibility is that the anti-tag antibodies disrupt the binding of Nef-HF to PAK-2 during immunoprecipitation of cell extracts or interfere with PAK-2 autophosphorylation in the in vitro kinase assay.

Although the C-terminal HA/FLAG tag did not disrupt PAK-2 activation or CD4 down-modulation, it did impact the ability of SF2 Nef to down-regulate MHC-1. Even though this is also the case for NA7-HF, the defect in MHC-1 down-regulation with NA7-HF may be due to the reduced steady state levels of the protein in CEM cells. The MHC-1 down-regulation defect in SF2 Nef with the C-terminal HF tag may be a result of steric hindrance and/or excess negative charge. To determine whether Nef is intolerant to large amino acid additions to its C-terminus, we functionally characterized two Nef-GFP fusion proteins.

Nef proteins fused at the C-terminus with GFP have been used to follow the localization of Nef in lipid rafts during immunological synapse formation (Fenard et al., 2005), analyze the effect of Nef on calcium release from intracellular stores (Fenard et al., 2005), determine the role of Nef’s dileucine sorting motif in its subcellular distribution (Craig et al., 2000), correlate the intracellular localization of Nef with CD4 down-modulation (Greenberg et al., 1997) and demonstrate co-localization of Nef with MHC-I in the perinuclear region of cells (Williams et al., 2002). In our studies, Nef-GFP fusion proteins were fully functional for CD4 down-modulation and partially functional for MHC-I down-modulation. However, fusion of GFP to the C-terminus of both NA7 and SF2 resulted in defective PAK-2 activation by Nef (SF2-GFP resulted in approximately a third of the activity as SF2, and NA7-GFP was essentially nonfunctional). Western blot analysis indicates that these differences in PAK-2 activation are not due to different levels of protein expression or inability of the polyclonal anti-Nef antibody to efficiently immunoprecipitate Nef-GFP. Fusion of the GFP protein may sterically hinder the interaction of the critical phenylalanine residue at position 191 of Nef with PAK-2 or other proteins involved in the activation of PAK-2 by Nef.

Conversely, the ability of SF2-GFP and NA7-GFP to down-modulate MHC-I suggests that the defect in MHC-I down-modulation observed with SF2-HF and NA7-HF is not due only to steric hindrance. An alternative explanation for the defect may be the highly negative charge of the HF tag (8 D, 2 K, 1 R). We tested this hypothesis by functionally analyzing Nef-GH7. SF2-GH7 and NA7-GH7 were found to be functional for MHC-I down-regulation, suggesting an altered conformation or association of Nef with C-terminal negative charges that are incompatible with MHC-I down-modulation. However, the size of the tag may contribute to the defect, since the HF tag is 28 amino acids whereas the GH7 tag is only eight amino acids. SF2-GH7 and NA7-GH7 were fully functional for PAK-2 activation (Fig. 5 and data not shown), confirming our hypothesis that the defect with SF2-GFP may be due to C-terminal addition of the large fusion protein.

Deletion of the RAEP22–25 duplication in SF2 has a negligible or no effect on any of the Nef functions studied (O’Neill et al., 2006). Furthermore, analysis of a compilation of 1,643 Nef sequences yielded a large number of Nefs with 2–10 amino acid duplications in the 17–26 amino acid region (O’Neill et al., 2006). Since this region can tolerate duplications, we anticipated that Nef function would be minimally disrupted by replacement of the RAEP duplication in SF2 with a peptide tag. This was the case for the single HA tag insertion of nine amino acids. However, anti-HA immunoprecipitations and Western blot analysis indicated that the single HA tag was poorly recognized by anti-HA antibodies. Thus, we inserted HA/HA or HA/FLAG/HA peptide tags at amino acid 24. Nefs containing these tags, although efficiently immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies, demonstrated a significant defect in MHC-I down-modulation. The reverse correlation between antibody recognition and MHC-I down-regulation exhibited by HA-SF2 Nef and HA/HA or HA/FLAG/HA-SF2 Nefs suggest previously undetected conformational constraints in the N-terminal region of Nef that are important for its ability to down-regulate MHC-I. These results may be explained by an interaction between the first α helix (R17ERM20RRAEPA26) and the ordered core of the Nef protein or another protein which is required for MHC-I down-regulation. In fact, deletions of this helix or mutation of M20 to A has been shown to be deleterious to MHC-I down-regulation (Akari et al., 2000; Blagoveshchenskaya et al., 2002; Mangasarian et al., 1999; Williams et al., 2005). An alternate hypothesis would be that the first α helix has several arginine residues positioned to enable interaction with phospholipids in the cellular membrane (Arold and Baur, 2001). Addition of the negative HA/HA and HA/FLAG/HA tags within the membrane anchor of Nef could interfere with Nef’s association with the membrane.

PAK-2 activity was co-immunoprecipitated with HA/HA-SF2 Nef and HA/FLAG/HA-SF2 Nefs when lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Nef antibodies. However, less than ten percent of the PAK-2 activity was immunoprecipitated when anti-HA antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation, despite the fact that these antibodies efficiently immunoprecipitated the bulk of Nef. These results are strikingly similar to those obtained with the C-terminal HA/FLAG tag. As these results were unanticipated, more studies including the possible role of the N-terminal region of Nef on PAK-2 activation will be required to elucidate these findings.

In summary, peptide tags were added to Nef’s C-terminus or proximal to the N-terminus and the effect of these sequence modifications on Nef function was determined. We discovered disruptions in Nef function with respect to MHC-I down-modulation with the addition of peptide tags to either region. The defect with MHC-I down-modulation with the C-terminal modifications was found to be mostly due to the negative charge of the added sequences and not to their relative size. This finding is consistent with the +2 net charge on the 27 amino acid C-terminal extension found in SIVmac239 Nef and with the observation that the intact C-terminus of SIVmac239 Nef is required for MHC-1 down-regulation (Swigut et al., 2004). We also observed disruption of PAK-2 activation with a C-terminal GFP fusion protein. These results are consistent with a functional model of Nef effecting multiple functions by forming distinct complexes with host cell proteins (Arold and Baur, 2001; Geyer, Fackler, and Peterlin, 2001). Furthermore, these results suggest that regions of Nef near its N and C-terminus have subtle structural constraints imposed by one or more of these complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture conditions

293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Cellgro, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Cellgro), 100 IU penicillin/ml, 100 μg streptomycin/ml, and 2 mM glutamine (Cellgro), and were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 10% carbon dioxide. CEM cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 IU penicillin/ml, 100 μg streptomycin/ml, and 2 mM glutamine, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Cellgro) and were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% carbon dioxide.

Plasmid expression constructs, transfections, and transductions

NA7 and NA7-HF (HF = DTYRYIANATYPYDVPDYAGDYKDDDDK) were obtained from Dr. Jacek Skowronski (Janardhan et al., 2004). SF2, SF2-HF, SF2-GH7, SF2-GFP and NA7-GFP were constructed using standard molecular biology techniques. HA-SF2 Nef was cloned by introducing a BssHI restriction site at amino acid 24 of SF2 Nef by site-directed mutagenesis, converting E24Q. This made the downstream BlpI restriction site unique. Complimentary oligos with overhangs were made and annealed at ratio of 1:1. Serial dilutions of annealed oligos were ligated with SF2 Nef E24Q cut with BssHI and BlpI to yield HA-SF2 Nef (HA = 9 amino acids, YPYDVPDYA). HA/HA-SF2 Nef (HA/HA= 19 amino acids, YPYDVPDYAGYPYDVPDYA) and HA/FLAG/HA-SF2 Nef (HA/FLAG/HA = 29 amino acids, YPYDVPDYAGDYKDDDDKAGYPYDVPDYA) were made utilizing internal restriction sites incorporated into HA and HA/HA oligos respectively. Modified nef sequences were transferred to the mammalian expression vectors pcDNA3.1, pCG or pCGCG (Janardhan et al., 2004) or the retroviral vector pLXSN (containing the neomycin phosphotransferase gene) and sequenced. Insertion of epitope tags was also verified by Western blot using antibodies directed against HA or FLAG. Transient transfections of 293T cells were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions, with the exception that due to the high level of expression of the pCGCG and pCG plasmids, nanogram quantities (200–500) of these particular plasmids were used for transfection. As a control for transfection efficiency, pEGFP-N1 was included in the transfection mix. After transfection (40–48 hours), cells were harvested for Western blot analysis (200 μg of protein) and in vitro kinase assay (600 μg of protein). For transduction of CEM cells, pEQPAM (2μg) and pLXSN or various pLnefSNs (2 μg) were co-transfected into 293T cells to generate amphotropic vectors. At 40–48 hours after transfection, the vector-containing media was collected for transduction using standard techniques.

Western blot analysis

HIV-1 Nef expression was determined using sheep polyclonal anti-HIV-1 Nef serum (1:3000) followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated rabbit anti-sheep immunoglobulin G (IgG; 1:10,000; Chemicon International Inc., Temecula, CA) or mouse anti-HIV-1 Nef antibodies (EH1; 1:10,000; AIDS Research and Reference Program) followed by HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000; Zymed, San Francisco, CA). GFP expression was determined using mouse anti-GFP antibodies (1:4000; Zymed) followed by HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG.

In vitro kinase assay and immunoprecipitations

The assay for the Nef-associated kinase was performed essentially as described (Foster et al., 2001; Luo and Garcia, 1996; Sawai et al., 1994). HIV-1 Nef (and Nefs modified with peptide tags or fusion proteins) were immunoprecipitated from cellular lysates with sheep polyclonal anti-HIV-1 Nef serum, mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibodies (Covance, Berkeley, CA) or mouse anti-FLAG antibodies (M2; Sigma, Saint Louis, MO). For the in vitro kinase assays, immunoprecipitates bound to protein A beads were resuspended in kinase assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM sodium chloride, 5 mM magnesium chloride, and 1% v/v 5 Triton X-100). Subsequently, 30 μCi of γ-[32P]-ATP (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA) was added and reactions were incubated for 10 min at 30 °C. Kinase reactions were stopped by the addition of EDTA (45 mM) and processed as previously described (Arora et al., 2000). Alternatively, immunoprecipitates bound to protein A beads were washed five time in lysis buffer, eluted with 1X SDS sample buffer and analyzed by Western blot.

Quantitation of in vitro kinase reactions

The in vitro kinase reactions were quantitated from at least three different experiments using the Cyclone Storage Phosphor System (Packard, Meriden, CT).

Flow cytometry analysis

For analysis of cell surface CD4 and MHC-I levels, transduced cells (500,000) were first incubated with a mouse monoclonal antibody recognizing anti-haplotype A1, A11, and A26 MHC class I (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA) for 20 min on ice in the dark, and then the cells were washed twice in 2 ml of ice-cold phosphate buffered saline containing 5% FBS. Cells were then incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG for 20 min on ice. Cells were washed as indicated above and incubated for 20 min on ice with 2 μg of mouse IgG, and washed again. Cells were then incubated with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated IgG monoclonal antibody to human CD4 (Exalpha, Maynard, MA) for 20 min on ice. Stained cells were washed and analyzed on a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur instrument equipped with CellquestPro software. All fluorescence data were collected in log mode. CEM cells transduced with LXSN served as the positive control. For negative controls, mouse isotype antibody replaced anti-MHC class I, and PE-conjugated mouse IgG (Exalpha) replaced PE-conjugated anti-CD4. In Fig. 3B, cell surface down-modulation of CD4 was analyzed on the GFP-positive cell population by staining cells with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated IgG monoclonal antibody to human CD4 (Exalpha, Maynard, MA). MHC-I cell surface levels were analyzed on the GFP positive cell population using the mouse monoclonal MHC class I antibody indicated above, followed by allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG.

| PAK2 activation anti-Nef IP |

PAK2 activation anti-tag IP |

CD4 down- modulation |

MHC-1 down- modulation |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | SF2 | ++ | not done | ++ | ++ |

| NA7 | + | not done | +++ | +++ | |

| C-terminal tag/Fusion | SF2-HF | ++ | − | +++ | + |

| NA7-HF | + | − | ++ | − | |

| SF2-GFP | + | not done | ++ | ++ | |

| NA7-GFP | − | not done | +++ | ++ | |

| SF2-GH7 | +++ | not done | ++ | + | |

| NA7-GH7 | + | not done | +++ | ++ | |

| Internal tag | HA-SF2 | +++ | − | ++ | ++ |

| HA/HA-SF2 | +++ | − | ++ | + | |

| HA/FL/HA-SF2 | +++ | − | ++ | + |

+,++,+++ = relative activity, − = defective

Acknowledgments

We thank Jacek Skowronski for generously providing the pCGCG, pCGCGNA7 and pCGNA7-HF plasmids and to James Hoxie for the monoclonal anti-Nef antibody (EH1) that was originally obtained through the NIH AIDS Research & Reference Reagent Program. We greatly appreciate Michael Melkus, Anja Wege and Laura Baugh for assistance with flow cytometry and data analysis, and to Laura Baugh and Anja Wege for assistance with cell transductions and maintenance of cell lines. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI-33331 (J.V.G.). Alexa Raney was supported in part by National Institutes of Health training grant 5 F32 AI058541-03.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aiken C, Trono D. Nef stimulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral DNA synthesis. J Virol. 1995;69(8):5048–56. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.5048-5056.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akari H, Arold S, Fukumori T, Okazaki T, Strebel K, Adachi A. Nef-induced major histocompatibility complex class I down-regulation is functionally dissociated from its virion incorporation, enhancement of viral infectivity, and CD4 down-regulation. J Virol. 2000;74(6):2907–12. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.6.2907-2912.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arold S, Franken P, Strub MP, Hoh F, Benichou S, Benarous R, Dumas C. The crystal structure of HIV-1 Nef protein bound to the Fyn kinase SH3 domain suggests a role for this complex in altered T cell receptor signaling. Structure. 1997;5(10):1361–72. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arold S, Hoh F, Domergue S, Birck C, Delsuc MA, Jullien M, Dumas C. Characterization and molecular basis of the oligomeric structure of HIV-1 nef protein. Protein Sci. 2000;9(6):1137–48. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.6.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arold ST, Baur AS. Dynamic Nef and Nef dynamics: how structure could explain the complex activities of this small HIV protein. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26(6):356–63. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01846-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora VK, Molina RP, Foster JL, Blakemore JL, Chernoff J, Fredericksen BL, Garcia JV. Lentivirus Nef specifically activates Pak2. J Virol. 2000;74(23):11081–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.11081-11087.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benichou S, Bomsel M, Bodeus M, Durand H, Doute M, Letourneur F, Camonis J, Benarous R. Physical interaction of the HIV-1 Nef protein with beta-COP, a component of non-clathrin-coated vesicles essential for membrane traffic. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(48):30073–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson RE, Sanfridson A, Ottinger JS, Doyle C, Cullen BR. Downregulation of cell-surface CD4 expression by simian immunodeficiency virus Nef prevents viral super infection. J Exp Med. 1993;177(6):1561–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentham M, Mazaleyrat S, Harris M. The di-leucine motif in the cytoplasmic tail of CD4 is not required for binding to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef, but is critical for CD4 down-modulation. J Gen Virol. 2003;84(Pt 10):2705–13. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagoveshchenskaya AD, Thomas L, Feliciangeli SF, Hung CH, Thomas G. HIV-1 Nef downregulates MHC-I by a PACS-1- and PI3K-regulated ARF6 endocytic pathway. Cell. 2002;111(6):853–66. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnahan PA, Yonemoto W, Greene WC. Cutting edge: SIV Nef protein utilizes both leucine- and tyrosine-based protein sorting pathways for down-regulation of CD4. J Immunol. 1999;163(6):2977–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs SD, Scholtz B, Jacque JM, Swingler S, Stevenson M, Smithgall TE. HIV-1 Nef promotes survival of myeloid cells by a Stat3-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(27):25605–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103244200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Wang X, Sawai E, Cheng-Mayer C. Activation of the PAK-related kinase by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef in primary human peripheral blood lymphocytes and macrophages leads to phosphorylation of a PIX-p95 complex. J Virol. 1999;73 (12):9899–907. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9899-9907.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl S, Greenough TC, Krumbiegel M, Greenberg M, Skowronski J, Sullivan JL, Kirchhoff F. Modulation of different human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef functions during progression to AIDS. J Virol. 2001;75(8):3657–65. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3657-3665.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowers MY, Spina CA, Kwoh TJ, Fitch NJ, Richman DD, Guatelli JC. Optimal infectivity in vitro of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 requires an intact nef gene. J Virol. 1994;68(5):2906–14. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2906-2914.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins KL, Chen BK, Kalams SA, Walker BD, Baltimore D. HIV-1 Nef protein protects infected primary cells against killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature. 1998;391(6665):397–401. doi: 10.1038/34929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig HM, Pandori MW, Guatelli JC. Interaction of HIV-1 Nef with the cellular dileucine-based sorting pathway is required for CD4 down-regulation and optimal viral infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(19):11229–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig HM, Reddy TR, Riggs NL, Dao PP, Guatelli JC. Interactions of HIV-1 nef with the mu subunits of adaptor protein complexes 1, 2, and 3: role of the dileucine-based sorting motif. Virology. 2000;271(1):9–17. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenard D, Yonemoto W, de Noronha C, Cavrois M, Williams SA, Greene WC. Nef is physically recruited into the immunological synapse and potentiates T cell activation early after TCR engagement. J Immunol. 2005;175(9):6050–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JL, Molina RP, Luo T, Arora VK, Huang Y, Ho DD, Garcia JV. Genetic and functional diversity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype B Nef primary isolates. J Virol. 2001;75(4):1672–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.4.1672-1680.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JV, Foster JL. Structural and functional correlates between HIV-1 and SIV Nef isolates. Virology. 1996;226(2):161–6. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JV, Miller AD. Serine phosphorylation-independent downregulation of cell-surface CD4 by nef. Nature. 1991;350(6318):508–11. doi: 10.1038/350508a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer M, Fackler OT, Peterlin BM. Structure--function relationships in HIV-1 Nef. EMBO Rep. 2001;2(7):580–5. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer M, Munte CE, Schorr J, Kellner R, Kalbitzer HR. Structure of the anchor-domain of myristoylated and non-myristoylated HIV-1 Nef protein. J Mol Biol. 1999;289(1):123–38. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer M, Yu H, Mandic R, Linnemann T, Zheng YH, Fackler OT, Peterlin BM. Subunit H of the V-ATPase binds to the medium chain of adaptor protein complex 2 and connects Nef to the endocytic machinery. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(32):28521–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200522200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg M, DeTulleo L, Rapoport I, Skowronski J, Kirchhausen T. A dileucine motif in HIV-1 Nef is essential for sorting into clathrin-coated pits and for downregulation of CD4. Curr Biol. 1998;8(22):1239–42. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg ME, Bronson S, Lock M, Neumann M, Pavlakis GN, Skowronski J. Co-localization of HIV-1 Nef with the AP-2 adaptor protein complex correlates with Nef-induced CD4 down-regulation. Embo J. 1997;16(23):6964–76. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg ME, Iafrate AJ, Skowronski J. The SH3 domain-binding surface and an acidic motif in HIV-1 Nef regulate trafficking of class I MHC complexes. Embo J. 1998;17 (10):2777–89. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy B, Kieny MP, Riviere Y, Le Peuch C, Dott K, Girard M, Montagnier L, Lecocq JP. HIV F/3′ orf encodes a phosphorylated GTP-binding protein resembling an oncogene product. Nature. 1987;330(6145):266–9. doi: 10.1038/330266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochrein JM, Wales TE, Lerner EC, Schiavone AP, Smithgall TE, Engen JR. Conformational features of the full-length HIV and SIV Nef proteins determined by mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2006;45(25):7733–9. doi: 10.1021/bi060438x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janardhan A, Swigut T, Hill B, Myers MP, Skowronski J. HIV-1 Nef binds the DOCK2-ELMO1 complex to activate rac and inhibit lymphocyte chemotaxis. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(1):E6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janvier K, Craig H, Le Gall S, Benarous R, Guatelli J, Schwartz O, Benichou S. Nef-induced CD4 downregulation: a diacidic sequence in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef does not function as a protein sorting motif through direct binding to beta-COP. J Virol. 2001;75(8):3971–6. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3971-3976.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kestler HW, 3rd, Ringler DJ, Mori K, Panicali DL, Sehgal PK, Daniel MD, Desrosiers RC. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell. 1991;65(4):651–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90097-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lama J, Mangasarian A, Trono D. Cell-surface expression of CD4 reduces HIV-1 infectivity by blocking Env incorporation in a Nef- and Vpu-inhibitable manner. Curr Biol. 1999;9(12):622–31. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80284-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Yu H, Liu SH, Brodsky FM, Peterlin BM. Interactions between HIV1 Nef and vacuolar ATPase facilitate the internalization of CD4. Immunity. 1998;8(5):647–56. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80569-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo T, Garcia JV. The association of Nef with a cellular serine/threonine kinase and its enhancement of infectivity are viral isolate dependent. J Virol. 1996;70(9):6493–6. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6493-6496.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangasarian A, Foti M, Aiken C, Chin D, Carpentier JL, Trono D. The HIV-1 Nef protein acts as a connector with sorting pathways in the Golgi and at the plasma membrane. Immunity. 1997;6(1):67–77. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangasarian A, Piguet V, Wang JK, Chen YL, Trono D. Nef-induced CD4 and major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) down-regulation are governed by distinct determinants: N-terminal alpha helix and proline repeat of Nef selectively regulate MHC-I trafficking. J Virol. 1999;73(3):1964–73. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1964-1973.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill E, Kuo LS, Krisko JF, Tomchick DR, Garcia JV, Foster JL. Dynamic evolution of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pathogenic factor, Nef. J Virol. 2006;80(3):1311–20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1311-1320.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piguet V, Wan L, Borel C, Mangasarian A, Demaurex N, Thomas G, Trono D. HIV-1 Nef protein binds to the cellular protein PACS-1 to downregulate class I major histocompatibility complexes. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(3):163–7. doi: 10.1038/35004038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renkema GH, Manninen A, Saksela K. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef selectively associates with a catalytically active subpopulation of p21-activated kinase 2 (PAK2) independently of PAK2 binding to Nck or beta-PIX. J Virol. 2001;75(5):2154–60. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2154-2160.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeth JF, Collins KL. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef: adapting to intracellular trafficking pathways. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70(2):548–63. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00042-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross TM, Oran AE, Cullen BR. Inhibition of HIV-1 progeny virion release by cell-surface CD4 is relieved by expression of the viral Nef protein. Curr Biol. 1999;9(12):613–21. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80283-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawai ET, Baur A, Struble H, Peterlin BM, Levy JA, Cheng-Mayer C. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef associates with a cellular serine kinase in T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(4):1539–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz O, Marechal V, Le Gall S, Lemonnier F, Heard JM. Endocytosis of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules is induced by the HIV-1 Nef protein. Nat Med. 1996;2(3):338–42. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swigut T, Alexander L, Morgan J, Lifson J, Mansfield KG, Lang S, Johnson RP, Skowronski J, Desrosiers R. Impact of Nef-mediated downregulation of major histocompatibility complex class I on immune response to simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2004;78(23):13335–44. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13335-13344.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei BL, Arora VK, Foster JL, Sodora DL, Garcia JV. In vivo analysis of Nef function. Curr HIV Res. 2003;1(1):41–50. doi: 10.2174/1570162033352057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M, Roeth JF, Kasper MR, Filzen TM, Collins KL. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef domains required for disruption of major histocompatibility complex class I trafficking are also necessary for coprecipitation of Nef with HLA-A2. J Virol. 2005;79(1):632–6. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.632-636.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M, Roeth JF, Kasper MR, Fleis RI, Przybycin CG, Collins KL. Direct binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef to the major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) cytoplasmic tail disrupts MHC-I trafficking. J Virol. 2002;76(23):12173–84. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.12173-12184.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiskerchen M, Cheng-Mayer C. HIV-1 Nef association with cellular serine kinase correlates with enhanced virion infectivity and efficient proviral DNA synthesis. Virology. 1996;224(1):292–301. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]