Abstract

While substantial research examines the dynamics prompting policy adoption, few studies have assessed whether enacted policies are modified to meet distributional equity concerns. Past research suggests that important forces limit such adaptation, termed here “policy inertia.” We examine whether block grant allocations to states from the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program have evolved in response to major technological and political changes. We assess the impact of initial allocations on later funding patterns, compared to five counterfactual distributional equity standards. Initial allocations strongly predict future allocations; in comparison, the standards are weak predictors, suggesting the importance of policy inertia. Our methodology of employing multiple measures of equity as a counterfactual to policy inertia can be used to evaluate the adaptability of federalist programs in other domains.

U.S. legislative history includes longstanding political debates over the fair distribution of federal funds. Liberal and conservative groups alike note uneven payments to states (Dubay 2006; Leonard and Walder 2000). Debates over federal allocation formulas are particularly heated because formulas clearly delineate winners and losers (NRC 2001). Key questions include how to define program objectives, measure need, identify data, and negotiate trade-offs between funding stability versus redirecting funds as needs change. Allocation formulas can create perverse incentives, such as inducing local programs to under-serve need to receive larger federal shares.

Once an allocation formula is established, it may be difficult to alter, even if stakeholders, policymakers, and analysts perceive it to be unfair. A study of federal aid programs over two decades found remarkably stable funding patterns over time, suggesting that “distributive policies are a function of basic, long-term power relationships within Congress” (Peterson 1995, p. 152). For example, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has argued that the state personal income measure used by Medicaid (a program jointly financed by the states and the federal government that provides healthcare to low-income populations) does not adequately address differences in local funding capacity (Allen 2003). Revising the formula to include a more reliable measure of “total taxable resources” would change allocations patterns. Politics have blocked numerous attempts to do so (Compson 2003).

Although all federal allocation formulas experience some inertia, it is unclear whether there is variation in the extent to which inertia prevails. It is unknown whether programs that address rapidly evolving policy problems would be less inertial. We develop a novel approach to investigate inertia in federal grant allocations and apply it to the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (RW), the largest federal program for HIV care. RW is a strong case study because substantial changes in HIV epidemiology and treatment have occurred since the program's inception.

We explore these issues in four stages. First, we hypothesize political mechanisms that may hinder the funding redistribution. Second, we provide the research context. We outline historical changes in HIV and their relevance to allocation decisions. We then describe RW and enumerate key amendments to the allocation formulas throughout the program's legislative history. Third, we delineate how we tested for policy inertia by comparing allocations to five distributional equity standards. We define inertia here as whether the interstate funding distribution remained static over time, rather than shifting according to equity standards. Fourth, we apply the mechanisms of inertia to this case and discuss how events in RW's political evolution contributed to the observed funding distribution. Although this analysis is specific to HIV policy, our approach to evaluate the fairness and flexibility of formula-based programs extends more broadly to any federalist program.

Mechanisms of Policy Inertia

We draw upon four theories to hypothesize underlying political mechanisms for inertia in federal allocation formulas: path dependency, redistributive politics, interest group politics, and punctuated equilibrium. Although these theories overlap, each provides a framework to understand inertia. We do not attempt to quantify which mechanism may be most influential in funding decisions; rather, we offer these accounts as possible causal mechanisms for a static distribution of funds.

Path Dependency

Path dependency, also termed policy feedback and policy lock-in, is one framework for policy inertia. This paradigm views public policies as endogenous to their development; rather than being outcomes of the political process, existing policies alter future policy options (Campbell 2007; Pierson 2004). Particular courses of action may be irreversible. Sequence and timing are crucial, and small early events can have a larger impact than large late events.

There are numerous mechanisms whereby distributional policies can undergo lock-in (Pierson 2000, 2004; Campbell 2007). Large fixed set-up costs may make it infeasible to alter the grant allocation process and funding stream structure. Learning effects increase local program managers' capacities to secure funds, making them more likely to support the status quo. Actors may use their political power to change allocation formulas, which can in turn increase their political power. Finally, a policy's enactment may cause policymakers and the public to believe that the problem has been solved, and policymakers may face formidable obstacles to modifying existing legislation.

Redistributive Politics

Legislators are drawn to legislation with geographic benefits for several reasons: concern for their constituents, the political value of obtaining benefits for voters, and avoiding issues that could be used against them in future elections (Arnold 1990). Psychologically, losses are more powerful than equivalent gains (Kahneman and Tversky 1984). Changes to an existing allocation formula will be difficult if some jurisdictions will lose funding: “Once citizens become addicted to a flow of benefits, legislators cannot bear to be associated with terminating them” (Arnold 1990, p. 137).

Interest Group Politics

Walker asserts that “…almost no important decision is made in Washington without the active, continuous involvement of some parts of the interest-group system” (1991, p. 1). Interest groups can influence allocation decisions by formulating questions, structuring policy choices, affecting public opinion, and defining debates. A policy's introduction may alter the political power and goals of interest groups, which in turn lobby to maintain benefits (Campbell and Morgan 2008). Conflict among interest groups affects the extent to which they influence funding decisions (Baumgartner and Jones 1993). Change is more difficult when multiple groups compete around different policy images. For example, groups representing constituents who are currently receiving benefits will work to maintain the status quo distribution.

Punctuated Equilibrium in Politics

Baumgartner and Jones (1993) draw upon social choice, policy subsystems, and agenda-setting literature to posit a theory of “punctuated equilibrium,” in which long periods of stability and incremental change are punctuated by volatile change. These “critical junctures” occur when policy images (how policies are understood) and policy venues (institutions and groups with the authority to enact policy decisions) interact: “When an agreed-upon image becomes contested, a policy monopoly is usually under attack, and the likelihood grows of a new mobilization (a wave of either criticism or enthusiasm) advancing the issue onto the macropolitical agenda” (True, Jones, and Baumgartner 1999, p. 103). An inability to shift the prevailing policy image and venue may yield little change.

Policy legacies, difficulties in redistributive policies, and interest group politics may promote policy inertia. In contrast, punctuated equilibrium theory predicts that a critical juncture may encourage change and the redistribution of funds. The introduction of new medical technologies and the changing demographics of HIV (including a focus on women and children) may have led to a critical juncture. We develop empirical methods to test for the existence of policy inertia and apply them to RW.

Research Context

The historical evolution of federal allocations of RW funds is an ideal case study to examine policy inertia. As the largest federal program devoted exclusively to HIV treatment, RW has been the focus of intense scrutiny by advocacy groups, bureaucracies, and legislators since its implementation. Significant shifts in HIV epidemiology and medical therapies have challenged policymakers to reconsider their definitions of fairness. The allocation formula has been modified extensively. The absence of substantial state matching requirements minimizes endogeneity between the size of a state's federal allocation and the jurisdiction's ability and willingness to contribute local funds. Finally, relatively complete funding data make it possible to quantify changes in allocation patterns.

Key Historical Changes in HIV Policy

Since HIV's emergence, there have been notable changes in epidemiology, medical treatment options, and healthcare financing. First, risk groups and the geographical distribution of cases have shifted. Early risk groups were white gay men and injection drug users. More recently, incidence has risen among minorities and women (CDC 2006). Initially, the case burden was predominately in large metropolitan areas (CDC 1989); since then, rural areas and the Southeast have experienced a rise in HIV incidence (CDC 2008). Socioeconomically disadvantaged populations have become disproportionately burdened by the epidemic (Committee 2005).

Second, the introduction of new antiretrovirals in the mid-1990s markedly decreased mortality. Consequently, HIV prevalence has risen, despite a relatively constant incidence of new infections (CDC 2008). Additionally, pharmaceutical advances engendered a shift from acute care to chronic disease management, and the need to treat comorbidities (Committee 2005).

The higher case burden and changing demographics have increased reliance on public programs to deliver HIV care (Levi and Kates 2000). How to manage increasing drug costs and utilization through RW has remained a salient topic (Aldridge and Doyle 2002).

The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program

The predominant public finance mechanisms for HIV care are Medicare, Medicaid, and RW (Committee 2004; Committee 2005; HRSA 2007). Enrollment into Medicare (a national health insurance program for the elderly and chronically disabled) and Medicaid requires meeting strict eligibility criteria. Most HIV-infected individuals receiving care through these programs qualify through the Social Security Income (Medicaid) and Social Security Disability Income (Medicare) pathways (KFF 2006a, 2008).

RW was established to serve as a “payer of last resort” for HIV-infected individuals with limited access to coverage (“Ryan White” 1990). RW targets individuals who have not yet progressed to AIDS (thereby meeting “disability” criteria) and who are not poor enough to qualify for Medicaid. RW is the largest federal program designed specifically for HIV care, with a budget of $2.1 billion in 2008 (Committee 2004; Committee 2005; HRSA 2007). Despite a linear increase in HIV prevalence in the U.S. (CDC 2008), RW has been flat-funded. In 2006 real dollars, federal funding rose steadily from $4.1 million in 1991 to $2.2 billion in 2001, stayed at this level until 2005, and then declined slightly.

RW is overseen by the Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA), with many program decisions devolved to states. Jurisdictions receive grants through several titles, the largest of which are Title I funds to “eligible metropolitan areas” (defined by population size and AIDS case count) and Title II funds to states and territories. (These titles have recently been renamed Parts A and B.) Approximately forty percent of all federal RW grants support local AIDS Drug Assistance Programs (ADAP), which provide medications to uninsured or underinsured individuals (Committee 2004; Committee 2005; HRSA 2007).

RW is a discretionary block grant program with a fixed budget set annually by Congress. Federal funds are distributed to local jurisdictions through complex allocation formulas, which were revised during reauthorization legislations in years 1996, 2000, and 2006 (HRSA 2007).

The original formula allocated one-half of the Title I base grant (to cities) according to cumulative case counts. The remaining Title I grant was a supplemental award funded through a separate allocation process. These allocations were based on “the number of persons with AIDS who needed care, demographic data such as poverty levels, the average cost of providing each category of services and the extent to which third-party payer coverage is available, and the aggregate amounts expended on services” (Committee 2004, p. 47). Title II grants (to states) were based on cumulative case counts reported in the prior two years and the relative per capita income of the state. The formula additionally stipulated minimum allocation floors for states with low case counts (Committee 2004).

Many policymakers have argued that the original formulas did not distribute funds fairly. Legislators have been cognizant of shifts in HIV epidemiology and have struggled with how to reallocate funds. Definitions of interstate equity and proposals to address funding disparities have varied across time and among policymakers (Martin, Pollack and Paltiel 2006). Two Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports have been commissioned on this topic, as well as numerous studies by the GAO.

Policymakers modified the formulas in several ways. Each reauthorization included extensive discussion on the case counting methodology. There was concern that the original formula's use of cumulative AIDS cases disproportionately benefited historical epicenters, due to counting of deceased cases (Scanlon 2005). Although the inclusion of HIV case counts (in addition to AIDS cases) was recognized as the best way to capture case burden, states' HIV surveillance systems varied substantially. From 1997 to 2006, Congress mandated the use of “estimating living AIDS cases,” and in 2006, the formulas were revised to include HIV and AIDS case counts (Committee 2004). Prior to the 1996 reauthorization, the GAO elucidated how the dual Title I and II structure counted urban cases twice, thus penalizing rural states (Scanlon 1995). In response, Congress stipulated that 20 percent of Title II funds be set aside for rural states (Committee 2004). In 2006, Congress changed the Title I allocation process and created separate funding streams for large cities and “transitional grant areas” (KFF 2006b). Finally, new supplemental awards were established for minority communities (Committee 2004) and states with “severe need” (Kates et al. 2006).

Several provisions were built into the revised formulas to prevent significant funding losses. Hold harmless provisions were originally implemented in 1996 after the introduction of “estimated living AIDS cases” and the set-aside for rural states (Committee 2004). Similar hold harmless provisions were added during each reauthorization, with levels as high as 100 percent after the 2006 reauthorization (Morgan 2007). The 1996 and 2000 reauthorizations additionally grandfathered areas eligible for additional Title I funding (Committee 2004). In 2006, the Title I supplemental award was reduced from one-half to one-third of the total Title I budget (KFF 2006b).

Methods

We derived five distributional equity standards that are specific to RW, which we use as counterfactuals to test for policy inertia. These standards define how interstate allocations might appear if the program had adapted to changes in the HIV epidemic or understandings of fairness. These standards were based on a review of Congressional testimony, political statements, GAO and IOM reports, and published literature. They reflect policymakers' pronouncements regarding the need to compensate for interstate disparities in: HIV incidence, socioeconomic status (SES) of program beneficiaries, existing program benefits, healthcare costs, and tax bases. Table 1 summarizes these standards.

Table 1.

Five standards of distributional equity in the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program.

| Equity Standard | Description | Origin | Measurement | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher AIDS Incidence | Additional funds to states representing the “leading edge” of the epidemic | Case counting methodology discussed extensively during 1996, 2000, and 2006 reauthorizations | Annual AIDS incidence, log-transformed | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1997-2004) |

| Disproportionate Prevalence of Lower SES Populations | Additional funds to states with larger minority populations and higher poverty rates | GAO analysis of whether these populations receive services in proportion to their representation; targeting these populations discussed during 2000 and 2006 reauthorizations | Proportion of states' cumulative AIDS cases (through 2005) that were 1) black and 2) Hispanic; proportion of states' residents living in poverty | Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (2005); U.S. Census Bureau (2000) |

| Weaker Program Benefits | Additional funds to states with less generous program benefits through their AIDS Drug Assistance Programs (ADAP) | National ADAP Monitoring Project annual reports (1997-2006); GAO report on wide interstate disparities in ADAPs (2006) | ADAP income eligibility ceiling (as percent of federal poverty level); number of drugs to treat and prevent opportunistic infections (OI) on state formulary, divided by total OI drugs available; presence of at least one cost containment measure that restricts program availability | National ADAP Monitoring Project (1997-2006); Federal Register |

| Differential Healthcare Costs | “Degree to which federal funds enable each [locality] to purchase a comparable level of services for its HIV population” | GAO analysis of “beneficiary equity” prior to 1996 reauthorization | Medicare Geographic Practice Cost Index (physician work component), aggregated from county to state level | Green Book (1997-2000); American College of Cardiology (2001-2002); Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (2003-2006); U.S. Census (1997-2006) |

| Compensation for Unequal Tax Base | “Degree to which [localities] are able to supplement federal funds to finance a comparable level of services with comparable burdens on their taxpayers” | GAO analysis of “taxpayer equity” prior to 1996 reauthorization | Medicare Geographic Practice Cost Index; U.S. Treasury measure of Total Taxable Resources (log-transformed) | U.S. Treasury (1997-2005) |

We estimated five separate regression models to compare dollar-per-case allocations (dependent variable) to states' initial allocations (primary independent variable) and the standards of equity (one model per standard). Each model contained time interaction terms with the main covariates. We used joint significance tests to: test whether the equity standards were significant predictors of funds, after adjusting for the allocation legacy; assess whether the initial allocation or the equity standards were more important predictors; and analyze time trends, including the persistence of the legacy effect. If inertia were present, the allocation legacy coefficients would be significant and positive, and the five equity standards would be weak predictors of funds. If the supplemental grant allocation process and the legislative changes successfully redirected funds, at least one equity standard would be significant. Negative time interactions with the allocation legacy variable would indicate funding redistribution.

Variables and Source Data

Public data for the fifty states and the District of Columbia were compiled from numerous sources. All funds were inflated to 2006 dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index. A Technical Appendix that contains additional details is available at Publius online.

Outcome Variable

States' log dollar-per-case allocations were used as the dependent variable. To be consistent with past IOM and GAO analyses of RW funding inequities, only Title I and Title II allocations were tabulated. We included base grants, competitive supplemental awards such as the minority health supplement, and the earmark for the AIDS Drug Assistance Program. Although RW has several other titles and components, Titles I and II account for 85 percent of total RW funds and provide support for state ADAPs (HRSA 2007). Only funds through Titles I and II are paid directly to states and localities; funds through the other components are paid to local organizations, providers, and a regional training program for healthcare providers. Whereas Titles I and II grants focus on medical and support services, funds through the other components finance activities such as capacity development, dental care, and healthcare provider training (HRSA 2007).

Congress revised the case counting methodology in 1997 and 2006. Between these dates, Congress mandated the use of “estimated living cases,” which were calculated as the cumulative sum of AIDS case counts over the prior decade, multiplied by year-specific survival weights. The CDC provided these survival weights and updated them biannually. We limit our panel to this era to avoid a disjuncture. For simplicity, we refer to estimated living cases throughout the analysis as “cases”, unless otherwise specified.

Allocation Legacy Main Effect

All models contained a covariate for the allocation legacy, measured as the cumulative funds received from 1991 to 1996 divided by the cumulative AIDS case count through 1996, on a log scale. Whereas the allocation outcome is based on year-specific data from 1997 to 2006, the allocation legacy independent variable is a time-invariant measure based on a state's initial allocation. Early allocations occurred before the widespread use of antiretroviral therapy in 1996; pharmaceutical innovations around this year reasonably demarcate different eras of HIV policy.

Equity Standard 1: Increased Funding for States with Higher HIV Incidence

The original legislation states Congress' intent to target resources to areas with the greatest case burden. Congress continued to emphasize this goal by reviewing case counting methodologies during each reauthorization.

We used annual AIDS incidence to assess whether a state was on the leading edge of the epidemic. Unlike the AIDS prevalence data used in the outcome's denominator, AIDS incidence captures new cases and is more sensitive to annual changes in case burden. HIV data could not be used because states have varied markedly in the quality of their surveillance data.

Equity Standard 2: Increased Funding for States with Lower SES Populations

HIV disproportionately affects minorities, women, and low-income individuals (Committee 2004). In 1995, Congress commissioned the GAO to evaluate whether these populations receive RW services in proportion to their representation in the HIV population (Nadel 1995). How to target services to these groups was a focus of both the 2000 and 2006 reauthorization legislations (Committee 2004).

We included variables for the proportion of states' cumulative AIDS cases (through 2005) that were black and Hispanic, and a variable for the proportion of state residents living in poverty.

Equity Standard 3: Additional Funds to States with Less Generous Program Benefits

Since 1995, the National ADAP Monitoring Project has surveyed state AIDS Drug Assistance Programs annually and reported widespread variation in program benefits and eligibility criteria (National ADAP Monitoring Project 2007). Reports have consistently described three domains of interstate disparities: eligibility criteria; extent of drugs covered on the formulary; and presence of program restrictions such as wait lists, capped enrollment, and limits on per-capita expenditure costs. The GAO has additionally described these interstate disparities (Crosse 2005).

Eligibility criteria are measured with the income eligibility ceiling as a percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). We measure the generosity of drug formularies via the percentage of drugs to treat and prevent opportunistic infections (OI) that were available on a state's formulary, with a denominator of all OI drugs recommended and available during that year. The presence of at least one additional program restriction is coded with a dummy variable.

Equity Standard 4: Consideration for Differential Healthcare Costs

Prior to the 1996 reauthorization, the GAO analyzed factors that inhibited “interstate equity” in Title I and II allocations. Allocations were compared to a standard of “beneficiary equity,” described as the “degree to which federal funds enable each [locality] to purchase a comparable level of services for its HIV population.” This was based on states' caseloads and differential per-case cost to provide services (Scanlon 1995). The IOM has also highlighted the need to consider differential care costs (Committee 2004). This equity standard is not unique to HIV policy. For example, Medicare employs differential reimbursement by geography (Steinwald 2005).

Differential healthcare costs were measured with the physician work component of the Geographical Practice Cost Index (GPCI), used by Medicare to adjust payments to physicians across the U.S. Data were aggregated to the state level.

Equity Standard 5: Consideration for Unequal Tax Bases

In its analysis of interstate allocations, the GAO also considered “taxpayer equity,” defined as the “degree to which [localities] are able to supplement federal funds to finance a comparable level of services with comparable burdens on their taxpayers.” As with its standard of “beneficiary equity,” this measure incorporated caseloads and differential per-case care cost. It also included jurisdictions' fiscal capacity to finance HIV services (Scanlon 1995). This standard is widely discussed by policymakers, evidenced by differential federal Medicaid matching rates (Steinwald 2005) and the use of “total taxable resources” in block grant allocations through the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (Compson 2003).

In the GAO's 1995 analysis of “taxpayer equity,” fiscal capacity was measured via the total taxable resource (TTR) index developed by the U.S. Treasury (Scanlon 1995). This regression model employed both the physician work GPCI and a term for the log TTR per capita.

Empirical Modeling Strategy

The data were analyzed with five random effects models, corresponding to five distributional equitiy standards. There are several reasons why we did not combine all standards into one regression. Most importantly, we constructed these models as separate counterfactuals for how allocations might have evolved, had they conformed to equity standards. Our aim was not to assess which standards are the most important predictors. This is also our motivation for not including additional political predictors.1 Second, many variables were multicollinear. For example, states with higher poverty rates (SES model) were more likely to have fewer taxable resources (differential tax base model). Third, we did not have a sufficient number of observations to include simultaneously all covariates and time interactions.

The five equity standards are only useful counterfactuals if they are not correlated with initial allocations. State characteristics are weakly correlated with initial allocations (1991-1996). Pearson correlation coefficients indicate that states with higher healthcare costs and AIDS incidence in 1997 received larger allocations in early years (R = 0.367 and 0.351, respectively; p<0.05). All other bivariate correlations were statistically insignificant.

The five regression models take the following general form:

where yij is the log dollar-per-case allocation to each state i in each year j, α is the population average intercept, Tj is a time vector (described below), TEVEN j is an even-year dummy variable (described below), Li is the state-specific allocation legacy main effect, Eqijk is a vector of state- and time-specific variables that correspond to the standard k under review, Zi is a vector of random coefficients for each state (described below), and εij is a random error term. Each model uses a different set of Eqk variables.

Plots of unadjusted allocations from 1997 to 2006 displayed biannual periodicity, reflecting the methodology used to construct the estimated living cases measure. To account for this artifact, all models included a dummy variable for the even years (TEVEN j). As a sensitivity analysis, models were run on only odd-or even-year data; these results did not change substantially.

After adjusting for the biannual periodicity, allocations followed a linear trend with a slope change at the year 2000, corresponding to the 2000 reauthorization and a change in presidential administration. Three time variables (Tj) were used to model this trend: linear time; a year-2000 dummy variable; and an interaction term between time and the year-2000 dummy variable.

We used a time-invariant allocation legacy main effect variable to assess the persistence of legacy effects. As the case-counting method differed before 1997, using a lagged legacy term would have dropped several years of data. For the allocation legacy main effect, the following set of time interaction terms were initially included (LiTj): a two-way interaction between linear time and allocation legacy, representing a slope change; a two-way interaction between the year-2000 dummy variable and allocation legacy, representing an intercept shift in 2000; and a three-way interaction among allocation legacy, linear time, and the year-2000 dummy variable, representing a slope change in 2000. These time interaction terms were considered for each standard (EqijkTj). Insignificant time interaction terms were dropped. The significance of these interaction terms tested changes in the allocation legacy effect and adherence to the various equity standards.

We present three types of regression-based output. First, the sign and significance of regression coefficients indicate whether each independent variable (allocation legacy and equity standards) was a positive or negative predictor of funds. The coefficient for the time interactions assessed whether their effects increased or attenuated over time. We assessed the relative importance of the legacy effect in comparison to the equity standards by comparing the joint F statistic for the full set of legacy covariates (main effect and time interactions) to the joint F statistic for the full set of distributional equity covariates. To illustrate the magnitude of each predictor, we calculated the difference in predicted allocations for states at the tenth and ninetieth percentile of each variable at the start and end of the time series. If there were a strong legacy effect, the joint F tests and difference in predicted allocations would be substantially larger for the legacy terms than for the equity variables. If the legacy effect attenuated, the variation in predicted allocations would be larger in 1997 than in 2006.

Three random effects (Zi) with an independence covariance structure accounted for within-state correlation. These corresponded to the intercept and the linear time trends (pre- and post-2000). This adjusted for within-state correlation by allowing for interstate variation in intercepts and slopes. We used an independence covariance because unstructured covariance models would not converge if three random effects were included. Qualitative conclusions were the same for models with three random effects and an independence covariance, compared to models with two random effects (intercept and general linear trend) and an unstructured covariance. We used random effects rather than state-level fixed effects because our main independent variable was time-invariant and we did not have sufficient degrees of freedom to include fixed effects.

Data were weighted by states' cases to minimize the impact of states with artificially high dollar-per-case allocations due to low case counts.

Findings

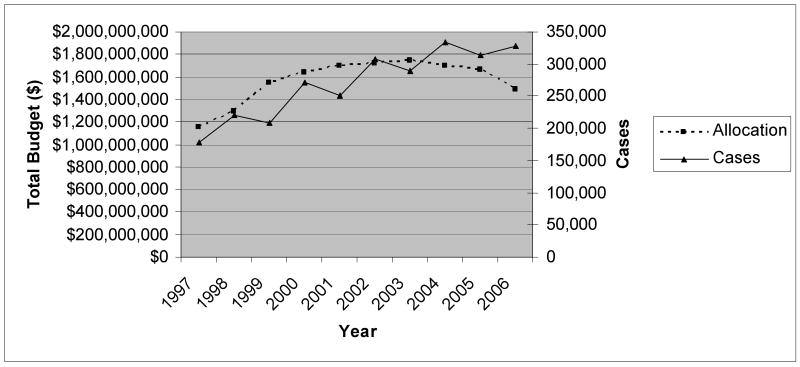

Figure 1 displays total Title I and II budget outlays and case counts for years 1997 to 2006. The case count rose steadily. From 1997 to 2000, the total budget (in 2006 real dollars) increased roughly in proportion to the increase in case load. From 2000 to 2003, the total budget increased slightly, although not in proportion to the rise in case count. After 2003, the total budget decreased. There was a wide range of dollar-per-case allocations, with some states receiving allocations over twice as large as their peers.

Figure 1.

Total federal budget outlays for Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (Titles I and II only) and number of cases reported (“estimated living cases”), for 50 states and the District of Columbia, years 1997-2006.

States' initial allocations varied widely. The mean dollar-per-cumulative AIDS case allocation was $1100 (st. dev. $525). Case-standardized allocations ranged from nearly $3000 (North Dakota) to less than $700 (Rhode Island).

Some of this variation is due to a subset of states with low case counts. Early allocation formulas provided a minimum level of funding each year, so these states received high case-standardized allocations. When the 10 percent of states with the lowest case counts were temporarily excluded, there was less variation in allocations. As discussed previously, we addressed this by weighting regression models by case counts, giving less weight to states with low disease burden.

Table 2 displays parameter estimates for the five equity models. Table 3 lists F statistics to test single and joint effects. Table 4 shows the absolute and percent differences in the predicted allocations for states at the tenth and ninetieth percentile of each independent variable, based on the regression coefficients.

Table 2.

Random effects regression models to test whether variation in interstate allocations (log $/case; years 1997-2006) through the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program is associated with a state's initial allocation (“allocation legacy,” 1991-1996) and distributional equity standards. Standard errors in parentheses.

| Equity Standard | Higher AIDS Incidence | Disproportionate Prevalence of Lower SES Populations | Weaker Program Benefits | Differential Healthcare Costs | Compensation for Unequal Tax Base |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.089*** (0.273) | 4.341*** (0.292) | 4.386*** (0.280) | 4.381*** (-0.294) | 4.170*** (-0.546) |

| Even-year dummy variable | -0.157*** (0.004) | -0.138*** (0.006) | -0.138*** (0.006) | -0.138*** (-0.006) | -0.140*** (-0.004) |

| Time | 0.643*** (0.062) | 0.470*** (0.095) | 0.466*** (0.094) | 0.469*** (-0.095) | 0.537*** (-0.059) |

| Post-2000 dummy variable | 0.970** (0.319) | -0.029 (0.339) | 0.150 (0.332) | -0.031 (-0.339) | 1.293*** (-0.252) |

| Time × post-2000 dummy variable | -0.504**** (0.080) | -0.264** (0.101) | -0.299** (0.098) | -0.263** (-0.101) | -0.507*** (-0.069) |

| Legacy | 0.660**** (0.041) | 0.630**** (0.044) | 0.609*** (0.040) | 0.606*** (-0.045) | 0.617*** (-0.042) |

| Legacy × time | -0.091**** (0.010) | -0.060**** (0.013) | -0.058*** (0.013) | -0.060*** (-0.013) | -0.069*** (-0.008) |

| Legacy × post-2000 dummy variable | -0.118* (0.049) | 0.041 (0.047) | 0.012 (0.046) | 0.041 (-0.047) | -0.140*** (-0.035) |

| Legacy × time × post-2000 dummy variable | 0.065**** (0.012) | 0.024 (0.014) | 0.030* (0.014) | 0.024 (-0.014) | 0.057*** (-0.009) |

| GPCI (physician work) | 0.009 (-0.052) | 0.028 (-0.051) | |||

| Total taxable resources per capita (log) | 0.010 (-0.049) | ||||

| Percent black AIDS cases | -0.044 (0.062) | ||||

| Percent Hispanic AIDS cases | -0.045 (0.169) | ||||

| Percent general population in poverty | -0.767* (0.374) | ||||

| Incidence (log) | -0.029* (0.014) | ||||

| Incidence × time | 0.019**** (0.005) | ||||

| Incidence × post-2000 dummy variable | 0.029 (0.025) | ||||

| Incidence × time × post-2000 dummy variable | -0.016* (0.006) | ||||

| Income eligibility | 0.011 (0.011) | ||||

| Income eligibility × time | -0.006*** (0.002) | ||||

| Percent OI drugs offered | -0.037 (0.029) | ||||

| Cost containment strategy | -0.045** (0.015) | ||||

| Time × cost containment strategy | 0.007** (0.003) | ||||

| N | 408 | 510 | 510 | 510 | 459 |

| -2 Log Likelihood | -886.3 | -669.7 | -692.3 | -664.6 | -971.8 |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

Table 3.

Joint F statistics, degrees of freedom (numerator, denominator), and significance level from random effects regression models to test whether variation in interstate allocations (log $/case; years 1997-2006) through the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program is associated with a state's initial allocation (“allocation legacy”; 1991-1996) and distributional equity standards.

| Equity Standard | Higher AIDS Incidence | Disproportionate Prevalence of Lower SES Populations | Weaker Program Benefits | Differential Healthcare Costs | Compensation for Unequal Tax Base |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legacy and time interactions | F=70.79*** df=4,346 |

F=61.07*** df=4,452 |

F=68.28*** df=4,447 |

F=53.44*** df=4,451 |

F=70.03*** df=4,399 |

| GPCI (physician work) | F=0.03 df=1,451 |

F=0.30 df=1,399 |

|||

| Total taxable resources per capita (log) | F=0.04 df=1,399 |

||||

| GPCI and total taxable resources | F=0.18 df=2,399 |

||||

| Percent black AIDS cases | F=0.51 df=1,46 |

||||

| Percent Hispanic AIDS cases | F=0.07 df=1,46 |

||||

| Percent general population in poverty | F=4.21* df=1,46 |

||||

| All demographic variables | F=1.82 df=3,46 |

||||

| Incidence (log) and time interactions | F=4.69** df=4,346 |

||||

| Income eligibility and time interaction | F=9.25*** df=2,447 |

||||

| Percent OI drugs offered | F=1.67 df=1,447 |

||||

| Cost containment and time interaction | F=4.32* df=2,447 |

||||

| All program benefits variables | F=6.43*** df=5,447 |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

Table 4.

Differences in predicted allocations for states with values at the tenth and ninetieth percentiles of the allocation legacy and variables to measure distributional equity standards.

| Variable | Difference at Start of Time Series1,2 | Difference at End of Time Series3 |

|---|---|---|

| Legacy | $2,914 (40.9 percent) | $1,599 (29.3 percent) |

| AIDS incidence | -$328 (-6.3 percent) | $207 (4.5 percent) |

| Percent black AIDS cases | -$145 (-2.8 percent) | -$123 (-2.8 percent) |

| Percent Hispanic AIDS cases | -$45 (-0.8 percent) | -$38 (-0.8 percent) |

| Percent general population in poverty | -$302 (-5.8 percent) | -$256 (-5.8 percent) |

| Income eligibility criteria | $118 (2.2 percent) | -$359 (-8.2 percent) |

| Percent OI drugs offered | -$184 (-3.5 percent) | -93 (-2.1 percent) |

| Cost containment strategy in place | -$237 (-4.6 percent) | $32 (0.7 percent) |

| Geographic Practice Cost Index | -$328 (-6.3 percent) | $207 (4.5 percent) |

| Total taxable resources per capita | $29 (0.5 percent) | $260 (5.5 percent) |

Start of time series is 1997.

Differences calculated as predicted value from states at ninetieth percentile minus predicted value from states at tenth percentile. Percent calculated as the percent change in predicted values, compared to states at the tenth percentile.

End of time series is 2006 for all variables except for AIDS incidence (2004) and total taxable resources per capita (2005).

In all models, the allocation legacy and its time interactions were highly significant. The relative magnitude of the F statistics and difference in predicted allocations suggest that this was the strongest predictor of funds. The coefficient for the legacy main effect was significant and positive, reflecting that states with larger case-standardized allocations from 1991 to 1996 received larger allocations from 1997 to 2006. The coefficients for the allocation legacy × time interactions (Table 2) are difficult to interpret due to the three-way interaction term and logarithmic transformations. Table 4 indicates that throughout the time period, states with high initial allocations received more funds than states with low initial allocations. However, this effect attenuated over time: the difference in predicted allocations for states at the ninetieth and tenth percentile of the initial allocation dropped from $2,914 (40.9 percent) in 1997 to $1,599 (29.3 percent) in 2006.

Equity Standard 1: Increased Funding for States with Higher AIDS Incidence

If RW funds targeted states representing the leading edge of the epidemic, the AIDS incidence variable would have a positive coefficient. The incidence main effect and the three time interactions are jointly significant (F=4.69; df=4,346; p=0.001). Initially, states with low AIDS incidence received slightly higher allocations, as shown by the negative coefficient for the main effect. By 2000, this relationship reversed, and in the later years of the period, states with higher AIDS incidence received higher allocations. Joint F tests indicate that the set of AIDS incidence and time interaction covariates was less significant than the set of legacy and time interaction covariates (F=70.79; df=4,346; p<0.001). This is confirmed by the difference in predicted allocations for states at the ninetieth and tenth percentile of AIDS incidence, which was -$328 and $207 for 1997 and 2004, respectively. Compared to the allocation legacy, AIDS incidence was a weak predictor of funds.

Equity Standard 2: Increased Funding for States with Lower SES Populations

Distribution of funds in accordance with this criterion of equity would predict increased allocations to states with larger minority and low-income populations. The poverty variable was significant (p=0.046) and negative, signaling that states with higher poverty rates received fewer funds. However, these results should be interpreted cautiously, because strong multicollinearity among the demographic variables made it impossible to untangle their individual effects. The joint F test for the three covariates was insignificant (F=1.82; df=3, 46; p=0.156), indicating that as a whole, these demographics were not predictive of allocations.

Equity Standard 3: Additional Funds to States with Less Generous Program Benefits

Distributing RW to states with poorer benefits would yield higher allocations to states with lower income eligibility ceilings, fewer OI drugs, and at least one cost containment strategy. This predicts a negative coefficient for the income eligibility and OI variables, and a positive coefficient for the cost containment variable. States with varying income eligibility had similar allocations, shown by the insignificant main effect term. However, by the end of the period, states with the strictest income eligibility criteria received slightly more funds; in 2006, states at the ninetieth percentile of income eligibility received $359 lower dollar-per-case allocations, compared to states at the tenth percentile. States that had at least one cost containment measure received a lower allocation in the beginning of the study period ($237), but by 2006, there was no difference. There was no observed association between the number of OI drugs offered on ADAP formularies and allocations. Compared to the allocation legacy, none of the program benefits variables and their interaction terms were strong predictors.

Equity Standard 4: Consideration for Differential Healthcare Costs

Allocations in accordance with differential healthcare costs would predict a positive coefficient for the GPCI variable. This coefficient was not significant, indicating that after adjusting for a state's allocation legacy, there was no observed relationship between a state's allocation and the cost of services.

Equity Standard 5: Consideration for Unequal Tax Bases

If funds targeted areas with reduced ability to supplement federal funds using local resources, there would be a positive coefficient for the GPCI and a negative coefficient for the TTR covariate. Neither was significant, indicating that after adjusting for a state's allocation legacy, there was no observed relationship between a state's allocation and the cost of services or the level of taxable resources.

Discussion

We tested for policy inertia in federal allocations through the Ryan White (RW) Program by comparing interstate allocation trends to states' initial allocations and five distributional equity standards. RW is a strong case study because substantial changes in HIV epidemiology and treatment have shifted needs across jurisdictions and engendered evolving conceptions of fairness. Each standard served as a counterfactual for how allocations could have evolved in response to changing needs and elite policymakers' discussions regarding the “fairness” of the allocation formulas. Three key findings emerge.

First, F statistics (Table 3) indicate that a state's initial case-standardized allocation (1991 to 1996), the “allocation legacy,” was the most important predictor of allocations in subsequent years (1997 to 2006). Although the magnitude of this effect attenuated by 2006, there remained a sizeable gap in allocations according to the size of a state's allocation legacy (Table 4).

Second, none of the standards of distributional equity was a strong predictor of funding. After adjusting for the allocation legacy, there was no evidence that funds were systematically distributed to address interstate disparities in healthcare costs, tax bases, or prevalence of lower SES populations. There was modest evidence for a funding distribution consistent with the goals of increased funding for states with higher AIDS incidence and extra funds to states with less generous program benefits. The magnitude of the relationships between allocations and these two standards was small, compared to the allocation legacy. Bivariate correlations between the allocation legacy and variables corresponding to the standards of distributional equity indicate that initial allocations did not conform to any of the five standards. This suggests that our null findings are not resultant from policymakers having made allocation decisions in accordance with these standards during the program's inception.

Third, results showed a modest attenuation of the legacy effect over time, attributable to formula modifications. This suggests incremental movement towards equity. However, the magnitude of this change is relatively small, compared to the allocation legacy. Time interactions with AIDS incidence, the presence of a cost containment measure, and income eligibility criteria were statistically significant (Table 2). However, the magnitude of these effects was very small, as shown by the differences in predicted allocations according to different levels of these measures (Table 4).

Three of the standards of distributional equity explored here (increased funding for states with higher HIV incidence, disproportionate prevalence of lower SES populations, and less generous program benefits) are directly related to changes in need resultant from shifts in HIV epidemiology. It is striking that allocation patterns have been relatively stable despite changes in these indicators. The other two standards (consideration for differential healthcare costs and unequal tax bases) reflect interstate heterogeneity that has been relatively stable over time. However, political debates over the merits of these two standards have changed. Given their importance in the 1996 reauthorization debate, it is notable that these standards were not significant predictors. Our findings are consistent with Inman's (1988) examination of federal aid to jurisdictions in the twentieth century, which found that allocation patterns could not be explained by the efficiency and equity public purpose arguments often used to support these programs.

Policy Inertia in Ryan White Allocations

We outlined four theoretical mechanisms that could account for inertia: path dependency, redistributive politics, interest group politics, and punctuated equilibrium. The following narratives describe how each could have influenced the allocation process. We do not test empirically which mechanism had the most influence on funding inertia; rather, we apply these theories to provide potential explanations for our findings.

Since the original RW legislation, the “problem” has shifted from a widespread recognition that HIV-infected individuals needed a safety net program to detailed methodological discourse on complex allocation formulas. The highly technical nature of the current debate hinders the reformulation of a policy image that would appeal to a wider public. It may be virtually impossible to alter the policy agenda and allocation process in the absence of a significant triggering event that would prompt the emergence of a new issue, dramatically shift the problem definition, or appeal to a different policy venue. However, issue reframing at the macro level is rare (Baumgartner et al. 2009).

Interest group fragmentation has impeded the formation of broad coalitions to influence allocation decisions. Powerful groups such as the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP, one of the most powerful and vocal AIDS activist groups in the early stages of the epidemic) have fractured due to gender and racial divisions, debates over internal participatory mechanisms, the use of insider versus outsider strategies, priorities and goals, and the politics of expertise (Epstein 1997). As new populations at risk have emerged, there has been less cohesive group identity. The population in which the epidemic is growing the fastest is largely poor, dependent on public programs for HIV care (Levi and Kates 2000), and with little political power. The waning political power of HIV interest groups and infighting may have reduced their ability to influence congressional leaders to redistribute funds.

As existing disease advocacy groups have diverged, new groups and constituencies representing the interest of both bureaucrats and disease advocates have formed in response to RW. They have conferred political resources to beneficiaries via access to decisionmakers and information on proposed legislations, created a readily-mobilized political base, fostered a sense of community among program beneficiaries, and lobbied and educated members of Congress. Furthermore, they have shaped the political goals of their beneficiaries. In the last reauthorization, the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD) worked with major stakeholders to affect the final outcome of the allocation process (Kates et al. 2006). The Communities Advocating Emergency AIDS Relief Coalition, originally formed by representatives of the initial sixteen Title I beneficiaries, has emphasized a goal of preventing funding losses (CAEAR 2008).

Loss aversion favors stability over change (Kahneman and Tversky 1984). Consequently, groups facing the threat of loss are more readily mobilized than groups with a potential for future gain. Defenders of the status quo can attempt to maintain the status quo by portraying change as risky and suggesting that change could be harmful (Baumgartner et al. 2009). The formation of new groups that seek to protect their resources is consistent with this narrative.

HIV and grandfathering provisions highlight enduring legacies of initial policies and the notion that “all politics is local.” Congressional leaders from jurisdictions with larger allocations have defended the double-counting of cases through the dual Title I and Title II funding streams by delineating “differences between the local, community-driven services provided in EMAs, and the state-level services funded by Title II” (Clinton 2005). They have further argued that dramatic cuts to their allocations would have negative ramifications for care systems that are effectively utilizing funds (Schumer 2006).

Policy learning has occurred throughout the program's history. NASTAD and HRSA have developed extensive technical support and peer mentoring. Some localities employ consultants and the Freedom of Information Act process to learn how to enhance grant scores and increase allocations (CAEAR 2004; Hamilton 2007). These grant-writing skills have helped to maintain funding distributions, even while a large fraction of total allocations has been based on supplemental grants. Consistent with a path dependency narrative, such policy learning has engendered positive feedback effects that make existing program arrangements increasingly difficult to alter. A complete restructuring of RW would require a new federal grant application process, retraining staff, and changes in key bureaucracies.

RW's continued block grant structure further suggests the enduring importance of initial policy decisions. The introduction of new therapies has made HIV care costlier due to more complicated drug regimens, reduced mortality, and the need to treat comorbidities. In light of these changes, the IOM assessed alternative strategies to improve HIV finance. It concluded that the best strategy would be to create a new entitlement program for HIV-infected individuals (Committee 2005). Although the report was released prior to the most recent reauthorization, turning RW into an entitlement program was not seriously discussed in Congress or by key interest groups. Legislation to expand Medicaid to cover treatment for individuals with HIV (before they qualify for Medicaid through progression to AIDS) has been repeatedly introduced since RW's inception, but never enacted (Westmoreland 2008).

Limitations

This analysis has several limitations. Most importantly, the state-level aggregation only allowed us to assess interstate transfers. We could not evaluate how state aid was transferred to lower levels of government within states or how states targeted services to individuals within their jurisdictions. In the model that considered variable prevalence of lower SES populations, it was impossible to untangle the independent effects of the multicollinear demographic variables. In the model that examined variable program generosity, program decisions may be endogenous to states' prior allocations. However, many states supplemented their allocations with local funds, suggesting that endogeneity between federal funding and program generosity may not pose too much problem for this analysis. Using ADAP benefits to measure program generosity ignores the 60 percent of Titles I and II that are not directly related to this service. Unfortunately, reliable panel data on other program benefits are unavailable. We did not test the adequacy of the general care system, which includes benefits through federal entitlement programs, public hospitals, and charity care. Finally, focusing on Titles I and II exclusively may limit the generalizability of our findings.

Most RW funds were distributed according to complex allocation formulas set by Congress, so most of the interstate variation in awards can be traced to this computation. Furthermore, most changes implemented during reauthorization legislations were not the result of explicit attempts by policymakers to achieve broader social goals on equity. This analysis attempts neither to explain all predictors of the size of a state's allocation nor to elucidate how legislative bargaining on the allocation formulas influences funding distributions. Rather, our contribution is a careful assessment of whether historical allocations are consistent with distributional equity goals or whether the interstate distribution of federal funds has been predominately driven by the legacy of initial allocations.

Conclusion

The design of federalist programs may engender inequities that are difficult to alter in the future. Despite vigorous political debate over interstate disparities and how to redistribute resources in response to shifts in the epidemic and available treatments, RW allocations remained consistent with the pattern set during the program's inception. Strong political forces contributed to this inertia.

The inertial quality of many federal allocation formulas has been well-described. For example, the allocation formula used to distribute Title I education grants uses lagged population data, which may not reflect recent changes in school district boundaries (NRC 2001). Block grants through the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration are explicitly structured to disproportionately benefit urban areas (NRC 2001), which may not reflect recent increases in drug abuse in rural areas (Hall et al. 2008). Grants for the State Homeland Security Program are allocated based on “risk analysis and the anticipated effectiveness of proposed investments by participants” (DHS 2009), suggesting that jurisdictions with greater grant-writing capacity may receive larger allocations. It is revealing that inertia also prevails in RW, because so many actors perceive HIV as a rapidly evolving problem.

Although this article focuses on allocations for HIV care, our results extend to other policy domains. We contribute to understandings of intergovernmental grants and federalism by introducing a methodology to explore empirically the degree to which allocations are inertial. This contrasts with past research that has focused on state-level characteristics that predict changes in funding distributions. Application of this methodology to a wide range of grant programs can answer broader questions, such as: Are all formula- and need-based programs as likely to be as legacy-driven and insensitive to changing environments? Are there attributes that would lead some programs to be more or less inertial? Are some political mechanisms more likely to contribute to inertia?

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mark Schlesinger and A. David Paltiel for helpful comments on earlier drafts, and Haiqun Lin for statistical expertise. We have also benefited from comments from participants of the Yale Health Policy Colloquium and Frank Baumgartner. Gregory Dybalski (GAO) generously provided historical data on RW funding, and Jill Ashman (HRSA) assisted with our collection of case count data. This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA015612) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (T32HS017589).

Footnotes

Another reason for excluding state-level political predictors is that because allocation decisions are made by Congress, the relevant political characteristics (such as changes in control of Congress and national economic conditions) are at the federal level. These are addressed through the time specification and random effects.

References

- Aldridge Chris, Doyle Arnold. Issue Brief: AIDS Drug Assistance Programs – Getting the Best Price? Washington, DC: National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors; New York, NY: AIDS Treatment Data Network; Menlo Park, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Allen Kathryn G. Medicaid Formula: Differences in Funding Ability among States Often Are Widened. Washington, DC: U.S. Printing Office; 2003. GAO Publication No. 03-620. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold R Douglas. The Logic of Congressional Action. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner Frank R, Jones Bryan D. Agendas and Instabilities in American Politics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner Frank R, Berry Jeffrey M, Hojnacki Marie, Kimball David C, Leech Beth L. Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2009. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Andrea L. Policy Feedbacks and the Political Mobilization of Mass Publics. 2007 Working paper. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Andrea L, Morgan Kimberly J. Policy Feedbacks and the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003: The Political Ramifications of Policy Change. 2008 Working paper. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) HIV/AIDS Surveillance. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS – United States, 1981-2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55(21):589–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [February 9, 2008]. HIV/AIDS Website. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv. [Google Scholar]

- Clinton Hillary R. Senators Clinton, Lautenberg, and Others Fight to Preserve Funding for States with High HIV/AIDS Populations, press release. 2005 2005 June 23; Issued. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Public Financing and Delivery of HIV Care, Board on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Public Financing and Delivery of HIV/AIDS Care: Securing the Legacy of Ryan White. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on the Ryan White CARE Act: Data for Resource Allocation, Planning, and Evaluation, Board on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Measuring What Matters: Allocation, Planning, and Quality Assessment for the Ryan White CARE Act. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Communities Advocating Emergency AIDS Relief (CAEAR) Coalition. Summer 2004 Update. Washington, DC: CAEAR Coalition; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Communities Advocating Emergency AIDS Relief (CAEAR) Coalition. [June 3, 2008];2008 [CAEAR Coalition Organizational Website.] Available at http://www.caear.org/coalition/index.

- Compson Michael L. Historical Estimates of Total Taxable Resources for the U.S. States, 1981-2000. Publius. 2003;33(2):55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Crosse Marcia. Ryan White CARE Act: Factors that Impact HIV and AIDS Funding and Client Coverage [testimony] (GAO Publication No 05-841T) Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Homeland Security Grant Program Overview. [June 1, 2009];2009 Available at http://www.dhs.gov/xprevprot/grants/gc_1216998599760.shtm.

- Dubay Curtis S. Federal Tax Burdens and Expenditures by State: Which States Gain Most from Federal Fiscal Operations? Washington, DC: Tax Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein Steven. Specificities: AIDS Activism and the Retreat from the “Genocide” Frame. Social Identities. 1997;3(3):415–438. [Google Scholar]

- Hall Aron J, Logan Joseph E, Tobin Robin L, et al. Patterns of Abuse among Unintentional Pharmaceutical Overdose Facilities. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;281(22):2127–2137. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton Tracy I. S.A. May Lose Funding for People with AIDS. San Antonio Express-News 2007 March 19; [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2007. [December 15, 2007]. Ryan White Program Website. Available at http://hab.hrsa.gov. [Google Scholar]

- Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Medicaid and HIV/AIDS Fact Sheet. 2006a Available from: http://www.kff.org/hivaids/upload/7172-03.pdf.

- Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) The Ryan White CARE Act: A Side-by-Side Comparison of Prior Law to the Newly Reauthorized CARE Act. 2006b Available from: http://www.kff.org/hivaids/upload/7531-03.pdf.

- Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Medicare and HIV/AIDS Fact Sheet. 2008 Available from: http://www.kff.org/hivaids/upload/7171-03.pdf.

- Inman Robert P. Federal Assistance and Local Services in the United States: The Evolution of a New Federalist Fiscal Order. In: Rosen HS, editor. Fiscal Federalism: Quantitative Studies. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1988. pp. 33–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman Daniel, Tversky Amos. Choices, Values, and Frames. American Psychologist. 1984;39:341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Kates Jennifer, Penner Murray, Crutsinger-Perry Beth, Carbaugh Alicia L, Singletones Natane. National ADAP Monitoring Project Annual Report. Washington, DC: National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors and Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard Herman B, Walder Jay H. The Federal Budget and the States: Fiscal Year 1999. Cambridge, MA: Taubman Center for State and Local Government, Harvard University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Levi Jeffrey, Kates Jennifer. HIV: Challenging the Health Care Delivery System. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(7):1033–1036. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Erika G, Pollack Harold A, Paltiel A David. Fact, Fiction, and Fairness: Resource Allocation under the Ryan White CARE Act. Health Affairs. 2006;25(4):1103–1112. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan Douglas H. Title XXVI of the PHS Act as Amended by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Treatment Modernization Act of 2006. Presented at National ADAP TA Meeting; Washington, DC. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nadel Mark V. Ryan White CARE Act: Access to Services by Minorities, Women, and Substance Abusers (GAO Publication No 95-49) Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- National ADAP Monitoring Project. [June 15, 2007];2007 [National ADAP Monitoring Project website.] Available at http://www.kff.org/hivaids/ADAP.cfm.

- National Research Council (NRC) Choosing the Right Formula: Initial Report. In: Panel on Formula AllocationsJabine TB, Louis TA, Schirm AL, editors. Committee on National Statistics. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson Paul E. The Price of Federalism. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pierson Paul. Not Just What, but When: Timing and Sequence in Political Processes. Studies in American Political Development. 2000;14:72–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pierson Paul. Politics in Time: History, Institutions, and Social Analysis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Act of 1990. Public Law. 1990 August 18;:101–381. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon William J. Ryan White CARE Act of 1990: Opportunities are Available to Improve Funding Equity (GAO Publication No 95-126) Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schumer Charles E. Schumer, Clinton, Lautenberg Call for Delay on Vote for Ryan White Funding until Impact on HIV/AIDS Programs in NY, NJ and across Nation Can Be Evaluated, press release. 2006 August;30:2006. Issued. [Google Scholar]

- Steinwald A Bruce. Medicare Physician Fees: Geographic Adjustment Indices Are Valid in Design, but Data and Methods Need Refinement (GAO Publication No 05-119) Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- True James L, Jones Bryan D, Baumgartner Frank R. Punctuated Equilibrium Theory: Explaining Stability and Change in American Policymaking. In: Sabatier PA, editor. Theories of the Policy Process. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1999. pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Walker Jack L., Jr . Mobilizing Interest Groups in America: Patrons, Professions, and Social Movements. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Westmoreland Timothy. Personal communication. 2008 2008 April 25; [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.