Abstract

We investigated the ability of certain triblock copolymer surfactant poloxamers of the form polyethylene oxide-polypropylene oxide-polyethylene oxide (PEO-PPO-PEO), to prevent formation of stable aggregates of heat denatured hen egg lysozyme. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and synchrotron small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) experiments were performed to study the thermodynamics and solution structures of lysozyme at temperatures between 20 and 90°C in the presence and absence of poloxamers with various molecular weights (8.4–14.3 kDa), but similar hydrophile/hydrophobe (PEO:PPO) ratio of 80%. Poloxmer 188 was found to be very effective in preventing aggregation of heat denatured lysozyme and those functioned as a synthetic surfactant, thus enabling them to refold when the conditions become optimal. For comparison, we measured the ability of 8 kDa polyethylene glycol (PEG) to prevent lysozyme aggregation under same conditions. The results of these studies suggest that poloxamers are more efficient than PEG in preventing aggregation of heat denaturated lysozyme, To achieve equivalence, more than an order of magnitude higher concentration of PEG concentration was needed. Apparently, the presence of a hydrophobic segment in the poloxamers increases their ability to target the hydrophobic region of the unfolded proteins and protect them from self association. Given their biocompatibility and the low concentrations at which they effectively facilitate refolding of denatured proteins, they may be useful in the treatment of burns and other conditions resulting in the denaturation of proteins.

Keywords: Heat denatured proteins, Surfactants, Poloxamer, Protein refolding, SAXS, DSC

INTRODUCTION

Denaturation of tissue proteins following exposure to supra-physiological temperatures or other various stresses is thought to be a major cause of tissue death. Enhanced thermotolerance can be induced in biological cells by heat stress preconditioning.15,21,27,43 The molecular mechanism of this thermotolerance involves increased biosynthesis of heat shock proteins (HSPs) that chaperone refolding of heat denatured proteins. The possibility to induce thermotolerance implies that increased concentrations of chaperones can reverse thermal damage to cells. Thus, if it is feasible to administer synthetic chaperones that augment or mimic the effect of natural chaperones, it may be possible to therapeutically augment thermotolerance following burn and similar trauma. In situations when normal cellular repair functions3,19,21 are incapable of managing the injury caused by heat, the currently available choices are limited for pharmaceutical interventions that could augment the chaperone function of the HSPs. Therefore, development of effective synthetic molecular chaperones which can be delivered through circulation to sites of tissue injury is badly needed to improve trauma therapeutics.

It is well established that several HSPs can catalyze solubilization and refolding of stable protein aggregates.4 The mechanism of refolding by HSPs, usually involves binding to the unfolded proteins to prevent or reduce the self-association of denatured proteins.13,45 In principle, unfolded proteins may spontaneously refold to their native states, or intermediate states, if their aggregation is prevented.10,29,33

Early attempts to mimic the chaperone function have focused on preventing self-association of unfolded proteins by using detergents.6–8,35,36 Rozema and Gellman developed a two-step method to assist refolding of proteins from a chemically denatured state.35,36 In the first step the unfolded proteins were captured by an ionic detergent (e.g., tetradecyltrimethylammonium bromide, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) during the dilution of the denaturant, thus preventing the aggregation of unfolded proteins driven by hydrophobic interaction. Subsequently, when the denaturant concentration decreased to a level that favors refolding of proteins, a cyclodextrin was used to strip the detergent from the protein and allow them to refold. This method, resembling the action of the E. coli GroEL/GroES system,18 has been shown to be viable in refolding several chemically denatured proteins such as carbonic anhydrase B, citrate synthase and lysozyme,9,17,28,35,36 as well as thermally denatured creatine kinase.36

Ionic detergents are generally toxic and cannot be used for clinical applications. On the other hand non-ionic polar polymers, such as PEG, are biocompatible and known to mimic the behavior of molecular chaperones.6–8 At concentrations that assure an efficient coating of the surfaces of the proteins in solution, low molecular weight PEG has been shown to increase the refolding yield of denatured proteins.7 Further studies revealed that the PEG molecules, in addition to sterically preventing protein-protein association2,23 at elevated temperatures, might alter the water structure at the interface of denatured proteins and initiate the protein refolding.37 Another interesting study reported that PEG bound to a thermo-reactive hydrophobic head [poly(propylene oxide)-phenyl group, (PPO-Ph)] can function as a temperature-responsive synthetic chaperone at 40–50°C.22,44 This result correlates well with the observation from mutational studies that E. coli GroEL residues important for substrate binding tend to be hydrophobic.39 Thus it would be interesting to explore and exploit non-ionic amphiphilic detergents with several characteristics similar to natural molecular chaperones as potential candidates for treatment of tissue injuries caused by heat, radiation and chemicals.

We have demonstrated that Poloxamers can bind to exposed hydrophobic domains of lipid bilayers32 facilitating the repair of disrupted cell membranes.26,31 Preliminary results showed that these polymers might be involved in the repair of proteins as well.24 Towards our long term goal to learn about the effects of Poloxamers in the recovery of the cells and tissues, we plan to gain a fundamental understanding of the interaction of these polymers with different proteins in their denatured states. We hypothesize that surfactant compounds, like the poloxamers, will absorb onto the abnormally exposed hydrophobic regions of the unfolded proteins, alter local hydrophobic interactions as well as alter the local surface tension in such a fashion as to facilitate protein disaggregation and refolding. In this report we present the thermodynamic and structural data demonstrating that P188 and similar surfactants can function as artificial chaperones of heat denatured lysozyme. Future studies will focus on strategies to protect several other proteins with different sizes as well as protein complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used DSC and SAXS to investigate the thermodynamic and structural aspects of lysozyme in solution at different temperatures and to investigate the ability of various amphiphilic triblock copolymer surfactants in preventing aggregation of thermally unfolded protein molecules and improve the refolding yield.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

DSC can characterize the aggregation of unfolded proteins and the reversibility of the thermal unfolding of proteins from which the refolding yield can be measured.29 For each sample we measured thermograms for two cycles of heating and cooling. The first thermogram reveals the characteristic temperature at which the proteins start to unfold and contains information about the difference in the heat capacity, enthalpy and entropy between the native and denatured states. The second thermogram, when compared to the first one, provides information on the thermal reversibility of the proteins and the extent of renaturation. Thus, the ratio of the areas under the heat capacity curves corresponding to the second (H2) and first (H1) heating processes can be used as a measure of protein renaturation. The difference between the value of for refolding in the presence of a given polymer and that for refolding in the absence of the polymer can be used to determine the efficiency of the polymers in refolding thermally denatured proteins. The behavior of the heat capacity curve at temperatures much higher than the mid-transition point Tm can be used to identify the aggregation of unfolded proteins. For instance, a massive aggregation of unfolded proteins corresponds to a negative slope of the heat capacity baseline at temperatures in the postdenaturation region, T ≫ Tm.5 Thus, DSC can be used to determine the protein:polymer stoichiometric ratio at which the aggregation is inhibited or reduced.

DSC Experimental Protocol

We carried out DSC experiments of lysozyme solutions at 11.6 mg/ml (0.77 mM) in Tris buffer at pH 7.0 and at both 3.76 mg/ml (0.25 mM) and 11.6 mg/ml (0.77 mM) in citrate-phosphate buffer at pH of 5.2. Concentrations of Poloxamer P188 (PEO76PPO29PEO76) in solutions were 6.5 mg/ml (0.77 mM) in Tris buffer and 0.1 mg/ml (0.012 mM) in citrate-phosphate buffer and those of Poloxamers P238 (PEO104PPO39PEO104), P338 (PEO132PPO60PEO132) and PEG (8KDa) were 8.8 mg/ml (0.77 mM), 11.24 mg/ml (0.77 mM) and 6.6 mg/ml (0.77 mM) in Tris buffer respectively. Initially the surfactant solution was loaded in both the sample cell and the reference cell of the calorimeter to obtain a baseline and equilibrate the system.

Thermal denaturation profiles for the above protein solutions were measured using a differential scanning calorimeter (VP-DSC, MicroCal Inc., Northampton, MA, USA). For equilibration and baseline subtraction purposes surfactant was added to both the sample and reference cells, and this eliminates the caloric contributions from the structural changes of the polymer molecules. Therefore the thermograms represent the effect of the structural changes of only the protein in the buffer and polymer solutions. DSC experiments were carried out over a temperature range of 20–100°C at a standard heating rate of 90°C/h. Two thermograms were recorded for each sample. After the first heating to 100°C, protein solutions were cooled to 20°C and allowed to equilibrate for 15 min prior to initiation of the second heating cycle. The transition enthalpy of protein denaturation was determined by calculating the area under the heat capacity peak. The baseline under the peak was approximated by a spline fit before and after the transition.34 The degree of renaturation was estimated from the ratio of the transition enthalpies for the renaturated and native proteins.

Small Angle X-ray Scattering

SAXS is a versatile tool to study the size, shape and aggregation of particles in a length scale of 1 to 50 nm at relevant conditions. It has been extensively used for the characterization of tertiary structural changes of proteins in solution, protein-protein interactions, micellization of block copolymers,30 protein aggregation, quaternary structures25,40,41 and the thermodynamics and kinetics of protein and RNA folding.14,20,40 As shown by Guinier16 the low Q region (Q = 4π/λ sin θ is the magnitude of the scattering vector where 2θ is the scattering angle and the λ is the wavelength of the X-rays) of the SAXS data can be approximated to be a Gaussian, . The slope and the Y-intercept of the line fit in the ln I(Q) versus Q2 plot in a Q range where Qmax ≤ 1.2/Rg provide the radius of gyration (Rg) of the particle and the intensity at zero angle (I(0)). Rg is the root-mean square distance of all the atoms in the scattering volume of the particle. If the SAXS data is available on an absolute scale I(0) can be used to determine the molecular weight (MW) of the scattering particle as I(0) ∝(ρProtein − ρsolvent)2 × MW × C, where C is the protein concentration in mg/ml, and ρProtein and ρsolvent are the electron densities of the protein and solvent.

A power-law behavior in the low Q region of the SAXS data with respect to Q for small protein solutions typically indicates the presence of aggregation and the magnitude of the exponent can be used to learn about the nature of aggregation. For instance, if proteins aggregate as string of beads the magnitude of the exponent will be around 1 and higher values indicate the presence of larger aggregates. SAXS derived Rg and MW for the aggregated systems correspond to second and first moments of their distribution respectively.

SAXS data of solutions consisting of proteins and polymers will provide information on the time and ensemble-averaged structures of both species. However the SAXS signals from the Poloxamer and PEG will be quite weak when compared to the protein due to their small X-ray scattering contrast. If the proteins and polymers do not form complexes then polymers contribution to the SAXS signal can be readily subtracted by a separate measurement of the polymer solution under identical solution conditions. However, if complexes do form its effect has to be taken into consideration. For a dilute solution consisting of lysozyme and polymer and lysozyme – polymer complex the scattered intensity can be expressed as

| (1) |

where I0 is a constant, nlys and npoly are the number densities of the lysozyme and polymer molecules, ncpl is the number density of the complexes, Δblys and Δbpoly are the electron density difference of the lysozyme and the polymer with respect to the solvent. Plys(Q) and Ppoly(Q) are the form factors of lysozyme and the polymer respectively, Pcpl(Q) is the form factor for the lysozyme/copolymer complex, and Ib is the incoherent background scattering. The form factors Plys(Q), Ppoly(Q), and Pcpl(Q) that describe the shapes of lysozyme, polymer and the complex are defined as

| (2) |

where the lysozyme and polymer molecules have been divided into zi and zj scattering elements respectively. For Plys(Q) and Ppoly(Q) zi = zj with both zi and zj scattering elements in the same molecule (lysozyme or polymer), while for Pcpl(Q) of the complexes the zi scattering elements are in the lysozyme and the zj scattering elements are in the copolymer.

In this study the scattering from the pure copolymer was subtracted by using the SAXS data measured for the neat polymer solutions at similar temperatures. Hence the measured scattering signals from the protein solutions can be described by the first two terms of Eq. (1). If the solution does not contain complexes then the second term will become zero and the background subtracted data will correspond solely to the lysozyme in solution. On the other hand, if complexes are present, the data will have contribution from the second term (cross-term) due to atomic vectors in the protein-polymer complexes. Of course, the magnitude of the cross-term will depend on the the size and concentration of the complexes as well as the contrast. In the present case, although the contrast for the polymer is quite low, if the complexes (larger size) do form, depending on their concentration, the cross-term will contribute to the overall scattering signal yielding higher Rg value (z-average) for the solutions containing lysozyme and polymer.

SAXS Experiments

The SAXS experiments of the lysozyme solutions were performed at the BioCAT beam line at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. We investigated solutions at a protein to Poloxamer ratio of 1:1 and protein to PEG molar ratio of 1:2. Computer-controlled Hamilton brand syringes (MICROLAB 500 System) injected sample into a thermostated flow cell made up of a 1.5 mm diameter cylindrical quartz capillary. To reduce the possibility of radiation damage, samples were measured under constant flow conditions. The scattering data measured at identical configuration for the buffer and protein solutions enabled proper background subtraction. At a given condition 5 one second measurements were made during heating from 25 to 80°C and cooling cycles at a rate of ~1°/min.

RESULTS

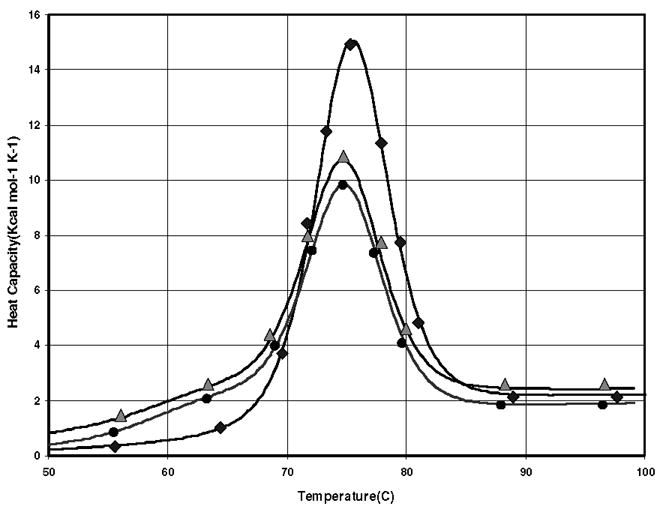

In the first set of DSC experiments we measured the stability of lysozyme in the range 20–90°C in the presence and absence of Poloxamers P188, P238 and P338 and PEG. Representative denaturation thermograms for 0.77 mM lysozyme in Tris buffer at pH = 7.0 are presented in Fig. 1. DSC curves for the first and second heating cycles of neat lysozyme solution are shown using diamond and circle markers, while that corresponding to the second heating cycle of the protein denaturation in the presence of 0.77 mM P188 are shown using triangle markers. It is clear that the heat capacity of the denatured lysozyme, in general, is higher than that of the native state.29 Table 1 summarizes the unfolding enthalpies for the first and second heating cycles of the protein solutions as well as the refolding yields in different solutions.

FIGURE 1.

Representative denaturation thermograms for 0.77 mM lysozyme in Tris buffer at pH = 7.0. DSC curves for the first and second heating cycles of neat lysozyme solution are shown using diamond and circle markers, while that corresponding to the second heating cycle of the protein denaturation in the presence of 0.77 mM P188 using triangle.

TABLE 1.

Results of the DSC experiments for 0.77 mM lysozyme (Lys) in Tris buffer at pH = 7.0 with and without surfactants at given molar ratios.

| Sample (molar ratio) | H1 (kcal mol−1) | H2 (kcal mol−1) | Number of experiments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lys | 109 ± 4 | 83 ± 5 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 5 |

| Lys + P188 (1:1) | 107 ± 4 | 95 ± 3 | 0.89 ± 0.01** | 5 |

| Lys + P238 (1:1) | 99 ± 10 | 84 ± 10 | 0.85 ± 0.07* | 4 |

| Lys + P338 (1:1) | 105 ± 1 | 81 ± 5 | 0.77 ± 0.05 | 4 |

| Lys + PEG (1:1) | 108 ± 6 | 78 ± 10 | 0.72 ± 0.07 | 5 |

| Lys + PEG (1:5) | 110 ± 1 | 89 ± 1 | 0.81 ± 0.01* | 4 |

Note. We present the average values (and standard deviations) for the unfolding enthalpies of the first (H1) and second heating (H2) cycles, and the refolding yields ( ). The refolding yields of Lys in the presence of P188, P238 and PEG (1:5) are significantly higher than in the absence of any surfactant (P = 0.0011, 0.03 and 0.04, respectively).

P < 0.05 vs. Lys,

P < 0.01 vs. Lys.

The area under the second thermogram, corresponding to the protein solution containing P188, is larger than that corresponding to the neat solution. This can be attributed to the higher amount of refolded proteins in the presence of P188. This behavior was also observed, although to a lesser extent, for P238 and P338 polymers but not for PEG (Table 1). At 1:1 protein-polymer ratio, PEG has little effect on the refolded fraction when compared to the neat solution. However, a significant increase in protein refolding was observed at 5:1 molar ratio of PEG:lysozyme.

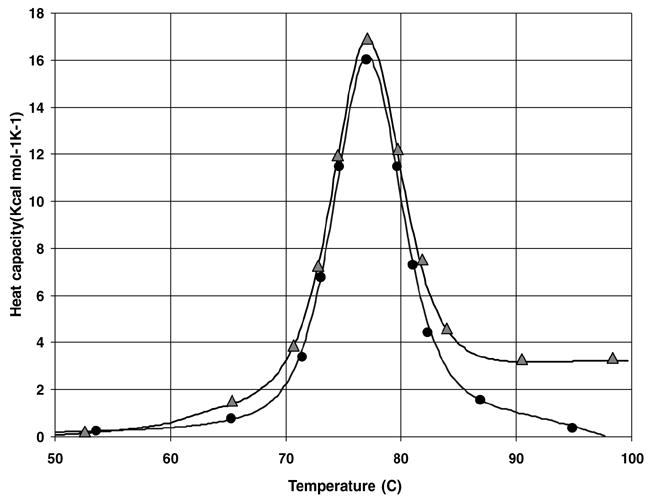

In Fig. 2 we show a denaturation thermogram (circle) of 0.77 mM lysozyme in a citrate phosphate buffer at pH 5.2 that seems to favor large protein aggregation as evidenced by a negative slope of the baseline at temperatures T > 85°C. In fact, after the DSC experiments, we observed that the solutions become turbid. Although a negative slope of the baseline can also be an experimental artifact in the way baseline corrections of the DSC traces are done, we did take great care in our experiments to rule out that possibility. Thus, after the initial measurement of an adequate baseline for the buffer solution, we repeated the measurements of the denaturation thermogram for the protein solution several times at 20–40°C to assure an accurate background subtraction. In conjunction with SAXS experiments (see below), we concluded that the negative slope of the baseline at temperatures T > 85°C is solely due to protein aggregation. Significant reduction in aggregation of the unfolded proteins was observed with the addition of 0.012 mM P188 to protein solutions (triangle). In this case, we can see a flattening of the calorimetric curve at higher temperatures. These results clearly demonstrate the ability of P188 in reducing the aggregation of unfolded proteins.

FIGURE 2.

A denaturation thermogram (circle) of 0.77 mM lysozyme in a citrate phosphate buffer at pH 5.2 with large protein aggregation. Significant reduction in aggregation of the unfolded proteins was observed with the addition of 0.012 mM P188 to protein solutions (triangle).

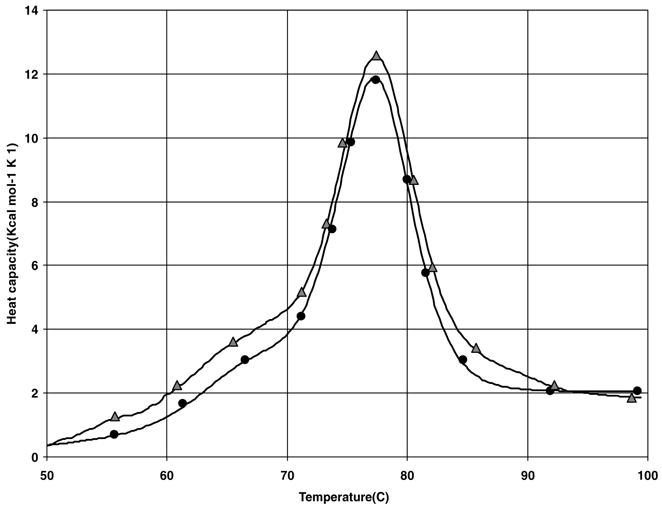

We also investigated the effect of polymer addition to protein solutions subjected to heating cycle. In Fig. 3 we present denaturation thermograms (second heating cycle) of 0.25 mM lysozyme in neat solution in citrate phosphate buffer at pH = 5.2 (circle) and in 0.1 mM P188 solution (triangle). Interestingly, the results in Fig. 3 show that the P188 can break the protein aggregates and thus increase the refolding yield of proteins. The lag time allowed for equilibration of the protein solution between the two consecutive heating cycles was 1 h. We observe that the thermograms no longer show the presence of large aggregation present in the previous case. Protein aggregates normally exist even at this low protein concentration but the population of unfolded proteins undergoing aggregation was substantially reduced. Since the average distance between proteins increases with the decrease in protein concentration, the probability of aggregation of unfolded proteins through collision via diffusion is significantly reduced in dilute protein solutions.12 Thus, the extent of aggregation and the size of the protein aggregates were small, such that the solutions with the P188 were less turbid after the DSC experiments. For lysozyme in neat solution the average value of the refolding yield . The polymer was incubated with the proteins in solution for 1 h prior to starting the second heating cycle. It can be readily seen that the area under the thermogram (triangles) is much larger indicating that P188 was able to refold a significant fraction of denatured proteins produced during the first heating cycle as the refolding yield increased to . When the values of and for lysozyme refolding in the absence and presence of P188 are compared it is clear that P188 does lead to a significant reduction in the denatured protein concentration.

FIGURE 3.

Denaturation thermograms (second heating cycle) of 0.25 mM lysozyme in neat solution in citrate phosphate buffer at pH = 5.2 (circle) and in 0.1 mM P188 solution (Triangle).

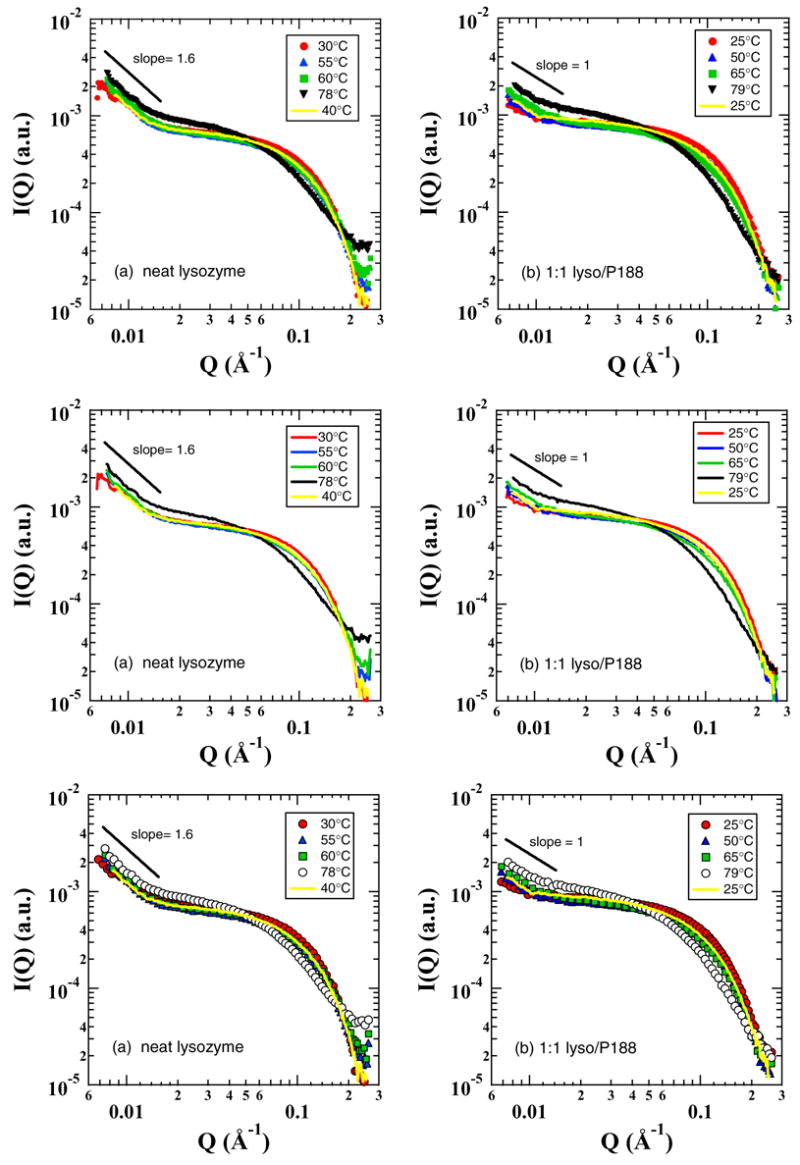

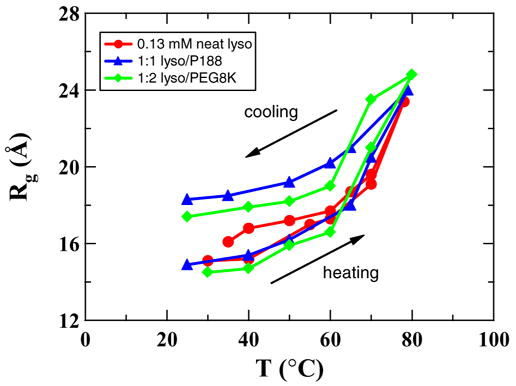

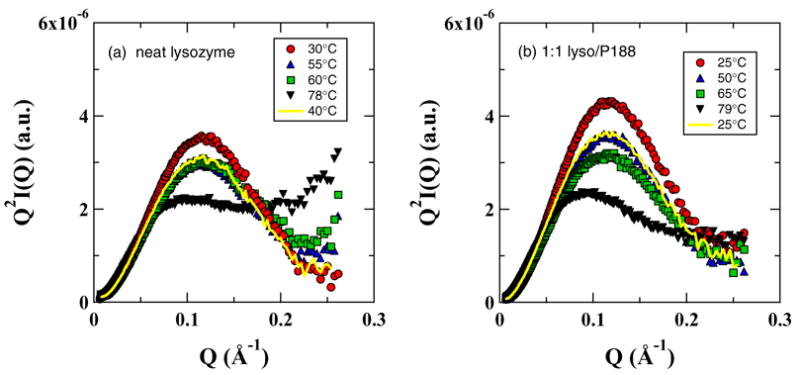

Figure 4a and b show representative SAXS data of 0.13 mM lysozyme in Tris buffer (pH 7.0) both in the absence and presence of P188 at 1:1 molar ratio during heating from 30 to 78°C and cooling to room temperature. It should be noted that 0.13 mM of P188 used here is much lower than its CMC of 0.357 mM at 55°C.1 The lack of micellization and the extremely low scattering contrast of P188 have significantly less effect on the overall scattering from lysozyme solutions. The log-log plot of the scattering data in the low Q region for the neat lysozyme solution (Fig. 4a) exhibits a power-law with a slope around −1.6 at all temperatures, indicating the presence of large aggregates, while in P188 solution the protein aggregation is substantially less as evidenced by a smaller power-law slope (≤1) in the low Q region (Fig. 4b). The scattering data in the intermediate to high Q region can be used to deduce the compactness of the individual proteins. It can be seen from Fig. 4a that the scattering data in the high Q region flatten with increasing temperature, indicating the unfolding of lysozyme during heating. The unfolding and refolding of lysozyme can be understood better by monitoring the radius of gyration (Rg) of the protein at different temperatures as shown in Fig. 5. It is clear that the average Rg of the protein increases from 15Å to 23 Å when temperature is increased from 30 to ~ 80°C and decreases with decreasing temperature. The maximum uncertainty in the measured Rg values is 0.5 Å. The small hysterisis in the Rg values for the neat lysozyme solution after one cycle of heating followed by cooling indicates the presence of a small amount of aggregation of lysozyme. Figure 5 also shows the temperature-dependent Rg values of lysozyme solutions in the presence of P188 and PEG. The average Rg values of lysozyme in both neat and P188 containing solutions are similar during a temperature increase up to 60°C. At higher temperatures, the Rg is larger by about 1.5 Å in the P188 solution when compared to the neat solution. Interestingly, lysozyme in P188 solution does not recover to the Rg in the neat solution at all temperatures during the cooling process. In fact, the average Rg value of lysozyme in P188 solution is about 3 Å larger after cooling to room temperature. We interpret this larger Rg value to be due to the presence of small amount of lysozyme-P188 complex. This conclusion is supported by the fact the heat denatured lysozyme in the presence of P188 recovered its enzymatic activity to the tune of 80 to 90% while the heat denatured lysozyme in neat solution could recover only up to 58% of the enzymatic activity of the unheated lysozyme.42 It should be noted that since the critical micelle temperature of 0.13 mM P188 is much higher than the temperatures used here, P188 will not form any micelles and the small size and scattering contrast of P188 molecules will have insignificant effect on the measured Rg values.

FIGURE 4.

Representative SAXS data of 0.13 mM lysozyme in Tris buffer (pH 7.0) both in the absence (a) and presence of the Polaxamer P188 (b) at 1:1 molar ratio.

FIGURE 5.

Radius of gyration (Rg ) of lysozyme as a function of temperature during heating and cooling cycles in neat and polymer solutions. The maximum uncertainty in the measured Rg values is 0.5 Å.

Kratky plots (Q2.I(Q) vs. Q) have been routinely used to monitor the compactness of macromolecules.14,38,41 The Kratky plot exhibits a plateau at the high Q region for particles with extended conformation, since the Debye function for scattering from a Gaussian coil has a limiting behavior of Q−2 at high Q. However, for globular/compact particles I(Q).Q2 values will decrease at high Q since I(Q) should vary as Q−4 for them. Thus, the I(Q).Q2 values at high Q can be used to learn about the shape and compactness of the scattering particles. The Kratky plots of the SAXS data in Fig. 4a and b for the lysozyme in neat and polymer solutions are shown in Fig. 6a and b. It is clear from Fig. 6a that lysozyme starts to unfold at T ~ 55°C and gradually expands from a compact globular shape to a random-coil structure at elevated temperatures (T > 78°C) and folds back to its compact shape upon cooling. This is consistent with the DSC data in Fig. 1 wherein the heat capacity starts to increase at 50°C indicating that both SAXS and DSC probe the same phenomenon. However, the decrease in peak intensity in the Kratky plot of the data at 40°C during cooling (Fig. 6a) indicates that some proteins aggregate and will not recover to their native conformation. Clearly the Kratky plots for lysozyme in P188 solutions are quite different from those for the neat solution. In contrast to neat solution, the Kratky plots for the P188 solution in Fig. 6b show slightly negative slopes. Although lysozyme at elevated temperatures will be extended, as evidenced by the similarity of the thermograms in both the neat and P188 containing lysozyme solutions (Fig. 1), the slightly higher Rg value and the less extended shape in P188 solution at T > 60°C suggest the presence of some protein/polymer complexes presumably formed through the hydrophobic interaction between the exposed hydrophobic residues of unfolded lysozyme molecules and the PPO segments of the P188.

FIGURE 6.

The Kratky plots of the SAXS data in Fig. 4a and b for the lysozyme in neat and polymer solutions.

DISCUSSION

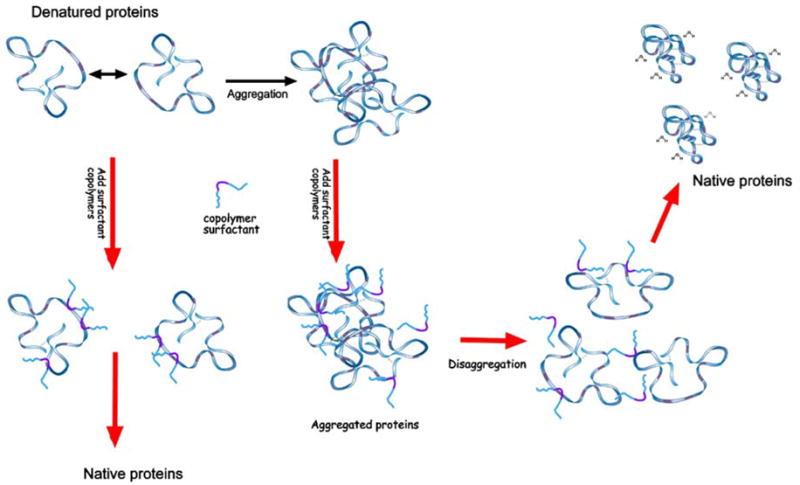

The results presented clearly demonstrate the viability of triblock copolymers in chaperoning the heat denatured lysozyme by reducing their aggregation. We believe that the PPO segments of P188 interact with the hydrophobic areas of the denatured lysozyme while the PEO segments provide added steric protection against the self-association of denatured lysozyme at higher temperatures (see Fig. 7). We also observed that P188 can also break aggregates of unfolded proteins (see Fig. 7). SAXS and DSC data show that the refoldability of proteins in solutions containing small aggregates of unfolded proteins increased with the addition of P188. These effects are similar to those of natural molecular chaperones.4

FIGURE 7.

Relevant processes in the protein unfolding/aggregation problem. Color codes are: blue for hydrophilic parts and pink for hydrophobic domains. Surfactant copolymers are able to prevent aggregation by coupling with the hydrophobic domains exposed to water. They can also break aggregated proteins and solubilize them. After the temperature of the solution returns to physiological values, proteins regain their native structures, while the polymer molecules apparently leave the protein structure.

The SAXS data show that the size and conformation of the protein are similar during heating up to 60°C in both solutions. Above this temperature, and also during cooling, the average Rg values of the system in P188 solution remain larger (by about 3 Å) when compared to that in the neat solution. At elevated temperatures, when lysozyme is unfolded, water becomes a poor solvent to the PPO segment of the Poloxamer and this enhances hydrophobic bonding between the exposed hydrophobic residues of the protein and the PPO segments. It should be noted that at these conditions P188 cannot form micelles. During cooling to room temperature, the hydrophobic interaction between the lysozyme and PPO segments tends to become weaker leading to the break down of the complexes and alteration of the dynamics of water at the hydrophobic interface11 will drive the lysozyme molecules to refold. Given the fast kinetics of the folding process it is likely that a small fraction of Poloxamer molecules remain entangled with lysozyme molecules during refolding. However, some of these complexes will break down with time as the SAXS data of solutions measured after 2 h of equilibration indicated the average Rg to recover to that of the native lysozyme (data not shown). The behavior of Poloxamer demonstrated here in assisting refolding of proteins resembles the chaperone function of some heat-shock proteins, such as Hsp70 and Hsp100.3,4,13,19,21,45

The SAXS data of the lysozyme in PEG solution resemble those of the P188 solution. The Rg values of lysozyme solution at PEG: lysozyme = 2:1 shown in Fig. 5 have values intermediate to those for the lysozyme in neat and P188 solutions during the cooling process.

The Poloxamers P238 and P338 have also been observed to provide protection against temperature induced aggregation, but their efficiency is low when compared to P188 (data not shown). This can be reconciled by the fact that although P238 and P338 have similar EO/PO composition ratio as P188 (80%), their CMC and CMT are much lower due to their higher molecular weights. For instance, CMC for P188, P238 and P338 at 45°C are 3.571 mM, 0.21 mM and 0.005 mM respectively. Their lower CMC values when compared to the polymer concentration of 0.13 mM used here lead to their micellization at much lower temperatures. Thus their depleted monomer concentration at elevated temperatures makes them unavailable to provide protection to the denatured proteins.

CONCLUSIONS

Currently burn trauma remains as a leading cause of death and disability throughout the world. To improve burn trauma outcomes, and perhaps the outcomes of similar injuries in which protein denaturation is a significant component, therapeutic strategies aimed at augmenting the natural cellular chaperone function to achieve proper refolding of proteins are needed. Our investigations reveal that certain Poloxamers are able to prevent the aggregation of unfolded lysozyme at elevated temperatures and thus enhance their refolding. The stoichiometric concentration required for this process is much lower for P188 than that for PEG, P238 and P338. The increased viability of P188 in the case of lysozyme might be due to its small hydrophobic PPO block that favors a better targeting of the hydrophobic residues of the unfolded proteins. Future studies will focus on the development of strategies to prevent aggregation of several proteins with different sizes and complexes using biocompatible Poloxamers as they will have important implications in protecting proteins from denaturation by thermal and other mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The research presented here has been supported by the National Institutes of Health, grants R01 GM61101 and R01 GM64757. Work benefited by the use of APS and IPNS funded by DOE-BES under contract #W-31-109-ENG-38 and the BioCAT beam line at the APS funded by NCRR/NIH.

References

- 1.Alexandridis P, Holzwarth JF, Hatton TA. Micellization of poly(ethy1ene oxide)-poly(propy1eneoxide)-poly(ethy1ene oxide) triblock copolymers in aqueous solutions: Thermodynamics of copolymer association. Macromolecules. 1994;27:2414–2425. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Annunziata O, Asherie N, Lomakin A, Pande J, Ogun O, Benedek GB. Effect of polyethylene glycol on the liquid-liquid phase transition in aqueous protein solutions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14165–14170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212507199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barral JM, Broadley SA, Schaffar G, Hartl FU. Roles of molecular chaperones in protein misfolding diseases. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Zvi AP, Goloubinoff P. Review: Mechanisms of disaggregation and refolding of stable protein aggregates by molecular chaperones. J Struct Biol. 2001;135:84–93. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2001.4352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burova TV, Grinberg NV, Grinberg VY, Rarity RV, Klibanov AV. Calorimetric evidence for a native-like conformation of hen egg-white lysozyme dissolved in glycerol. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1478:309–317. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cleland JL, Wang DI. Cosolvent assisted protein re-folding. Biotechnology. 1990;8:1274–1278. doi: 10.1038/nbt1290-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cleland JL, Hedgepeth C, Wang DI. Polyethylene glycol enhanced refolding of bovine carbonic anhydrase B. Reaction stoichiometry and refolding model. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13327–13334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleland JL, Builder SE, Swartz JR, Winkler M, Chang JY, Wang DI. Polyethylene glycol enhanced protein refolding. Biotechnology. 1992;10:1013–1019. doi: 10.1038/nbt0992-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Couthon F, Clottes E, Vial C. Refolding of SDS- and thermally denatured MM-creatine kinase using cyclodextrins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;227:854–860. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demetrius L. Thermodynamics and kinetics of protein folding: An evolutionary perspective. J Theor Biol. 2002;217:397–411. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2002.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Despa F, Fernández A, Berry RS. Dielectric modulation of biological water. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;93:228104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.228104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Despa F, Orgill DP, Lee RC. Effects on crowding on the thermal stability of heterogeneous protein solutions. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33:1125–1131. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-5780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis RJ, Hartl FU. Principles of protein folding in the cellular environment. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9:102–110. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)80013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang X, Littrell K, Yang Y, Henderson SJ, Seifert S, Thiyagarajan P, Pan T, Sosnick TR. Mg2+ dependent compaction of yeast tRNAPhe and the catalytic domain of the B. subtilis RNase P RNA determined by small angle X-ray scattering. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11107–11113. doi: 10.1021/bi000724n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glover JR, Lindquist S. Hsp104, Hsp70, and Hsp40: A novel chaperone system that rescues previously aggregated proteins. Cell. 1988;94:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guinier A, Fournet G. Small angle scattering of X-ray. Wiley; New York: 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson PE, Gellman SH. Mechanistic comparison of artificial-chaperone-assisted and unassisted refolding of urea-denatured carbonic anhydrase B. Fold Des. 1998;3:457–468. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(98)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartl FU. Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature. 1996;381:571–579. doi: 10.1038/381571a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaattela M. Heat shock proteins as cellular lifeguards. Ann Med. 1999;31:261–271. doi: 10.3109/07853899908995889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacob J, Krantz B, Dothager RS, Thiyagarajan P, Sosnick TR. Early collapse is not an obligate step in protein folding. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:369–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kregel KC. Heat shock proteins: Modifying factors in physiological stress responses and acquired thermotolerance. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:2177–2186. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01267.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuboi R, Morita S, Ota H, Umakoshi H. Protein refolding using stimuli-responsive polymer-modified aqueous two-phase systems. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 2000;743:215–223. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)00062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulkarni AM, Chatterjee AP, Schweizer KS, Zukoski CF. Effects of polyethylene glycol on protein interactions. J Chem Phys. 2000;113:9863–9873. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuo AF, Blossfield KM, Despa F, Betala P, Gissel H, Lee RC. Synthetic copolymer surfactants as molecular chaperones, Book of Abstracts: The Society for Physical Regulation in Biology and Medicine. 22nd Annual Meeting; Jan. 7–9; San Antonio. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lattman EE. Small angle scattering studies of protein folding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1994;4:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee RC, River LP, Pan FS, Wollmann RL. Surfactant-induced sealing of electropermeabilized skeletal muscle membranes in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4524–4528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lepore DA, Hurley JV, Stewart AG, Morrison WA, Anderson RL. Prior heat stress improves survival of ischemic-reperfused skeletal muscle in vivo. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:1847–1855. doi: 10.1002/1097-4598(200012)23:12<1847::aid-mus8>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Machida S, Ogawa S, Xiaohua S, Takaha T, Fujii K, Hayashi K. Cycloamylose as an efficient artificial chaperone for protein refolding. FEBS Lett. 2000;486:131–135. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makhatadze GI, Privalov PL. Energetics of protein structure. Adv Protein Chem. 1995;47:307–425. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mao G, Sukumaran S, Saboungi ML, Thiyagarajan P. PEO-PPO-PEO block copolymer micelles in aqueous electrolyte solutions: Effect of carbonate anions and temperature on the micellar structure and interaction. Macromolecules. 2001;34:4666. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marks JD, Pan CY, Bushell T, Cromie W, Lee RC. Amphiphilic, tri-block copolymers provide potent membrane-targeted neuroprotection. FASEB J. 2001;15:1107–1109. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0547fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maskarinec SA, Hannig J, Lee RC, Lee KYC. Direct observation of poloxamer 188 insertion into lipid monolayers. Biophys J. 2002;82:1453–1459. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75499-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plaxco KW, Simons KT, Ruczinski I, Baker D. Topology, stability, sequence, and length: Defining the determinants of two-state protein folding kinetics. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1177–1183. doi: 10.1021/bi000200n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Privalov PL, Potekhin SA. Scanning microcalorimetry in studying temperature-induced changes in proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1986;131:4–51. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)31033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rozema D, Gellman SH. Artificial chaperone-assisted refolding of denatured-reduced lysozyme: Modulation of the competition between renaturation and aggregation. Biochemistry. 1996;35:15760–15771. doi: 10.1021/bi961638j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rozema D, Gellman SH. Artificial chaperones: Protein refolding via sequential use of detergent and cyclodextrin. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:2373–2374. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saroff HA. Structure of deoxyhemoglobin: Ionizable groups and polyethylene glycol. Proteins. 2003;50:329–340. doi: 10.1002/prot.10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Segel DJ, Bachmann A, Hofrichter J, Hodgson KO, Doniach S, Kiefhaber T. Characterization of transient intermediates in lysozyme folding with time-resolved small-angle X-ray scattering. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:489–499. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sigler PB, Xu Z, Rye HS, Burston SG, Fenton WA, Horwich AL. Structure and function in GroEL-mediated protein folding. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:581–608. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thiyagarajan P, Henderson SJ, Joachimiak A. Solution Structure of GroEL and its Complex with Rhodanese by Small Angle Neutron Scattering. Structure. 1996;4:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trewhella J. Insight into biomolecular function from small angle scattering. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:702–708. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walsh AM, Mustafi D, Makinen M, Lee RC. A Surfactant Copolymer Facilitates Functional Recovery of Heat Denatured Lysozyme. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1066:321–327. doi: 10.1196/annals.1363.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weibezahn J, Tessarz P, Schlieker C, Zahn R, Maglica Z, Lee S, Zentgraf H, Weber-Ban EU, Dougan DA, Tsai FTF, Mogk A, Bukau B. Thermotolerance requires refolding of aggregated proteins by substrate translocation through the central pore of ClpB. Cell. 2004;119:653–665. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshimoto N, Hashimoto T, Felix MM, Umakoshi H, Kuboi R. Artificial chaperone-assisted refolding of bovine carbonic anhydrase using molecular assemblies of stimuli-responsive polymers. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:1530–1538. doi: 10.1021/bm015662a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Young JC, V, Agashe R, Siegers K, Hartl FU. Pathways of chaperone-mediated protein folding in the cytosol. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:781–791. doi: 10.1038/nrm1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]