Abstract

We report a very rare case of a congenital cervical spine anomaly. The low occurrence rate of this anatomic variant combined with the high frequency of cervical injuries in sports medicine made this case a diagnostic challenge on both emergency and orthopaedic departments. After reading, it should give the clinician a more consistent view in differentiating the traumatic or congenital origin of the disorder seen on radiographs, as well as what can be expected in the future when diagnosis is set.

BACKGROUND

Reports of combined anomalies of the posterior and anterior arch of the atlas are rare.1–3 Most of the reported cases were asymptomatic and were discovered coincidentally on preoperative or emergency room radiographs.1–3 Some of these were associated with an os odontoideum and, therefore, considered segmentally unstable.4,5 This case reports an asymptomatic bipartite atlas mimicking atlantoaxial instability following a rugby tackle.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 16-year-old boy presented to the emergency department after a rugby trauma. He fell on the back of his head following a tackle. At impact, his neck was forced into flexion with his chin touching his sternum after which he felt a “breaking” sensation in his neck. He remained conscious throughout. Given the mechanism of injury, cervical trauma was suspected and the patient was put in a stiff collar to immobilise the cervical spine. At the moment of presentation, he had a slight headache, mild neck pain and no pain in the upper extremities. Clinical examination showed no neurological abnormalities, full strength and preserved sensation in both upper extremities. Adequate analgesia was given and imaging was subsequently performed.

INVESTIGATIONS

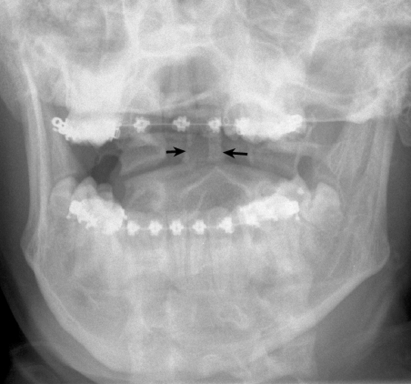

A cervical radiograph showed an asymmetry of the dens in anteroposterior trans-oral view (fig 1). There were no signs of trauma on the lateral view. A CT scan was ordered.

Figure 1.

Radiography: asymmetry of the dens in anteroposterior transoral view.

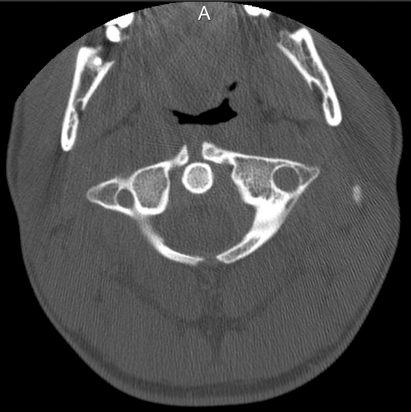

Cervical CT scan revealed an anteroposterior cleft of the atlas (fig 2). The previously seen atlantoaxial asymmetry on radiography was confirmed. No soft tissue abnormalities or swelling was found and smooth intact cortical margins were seen on the anterior and posterior fragments.

Figure 2.

CT: bipartite atlas, smooth intact cortical margins were seen on the anterior and posterior arch.

The collar was taken off and there was, on careful clinical exam, a full, pain free, range of motion of the cervical spine, with discomfort only at the endpoint of active motion. Isometric rotational resistance revealed muscular discomfort. Some tenderness was found at the mastoid processes bilaterally. There was no tenderness or localised swelling of the neck at the occipito-cervical level or any other level.

TREATMENT

It was decided that there was no acute bony injury and a soft collar was given for comfort.

The patient was admitted to the orthopaedic department for further neurological observations. Muscular discomfort increased on the first day after admission, but the neurological exam remained completely normal and the patient was discharged with a soft collar for comfort 48 hours later. At the time of discharge muscular pain had decreased and no neurological symptoms had occurred. The soft collar was discarded after 1 week.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

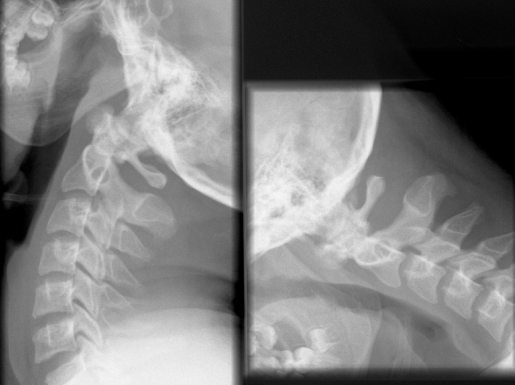

The patient was advised to stop playing contact sports, including rugby, and recommended to adjust his recreational activities. Stress radiographs were made 2 months after the injury and proved his anatomic deviation to be stable in hyperflexion and extension (fig 3). Further clinical evaluations were performed at follow-up 2 years after the trauma. The presence of this congenital disorder did not seem to influence our patient’s daily life. However, a minor cervical discomfort occurred regularly after practising sports as he mentioned soccer and snowboard. Physiotherapy was prescribed for some symptomatic relief.

Figure 3.

Stress radiography: stable cervical spine in flexion and extension.

DISCUSSION

The atlas is formed from three ossification centres: the anterior tubercle is formed from the anterior ossification centre and two lateral centres form the lateral masses and the posterior arch.1,2,6 The two lateral ossification centres appear at about 7 weeks of gestation. Ossification proceeds from lateral to dorsal. A cartilaginous cleft between the bony posterior hemiarches is still present at the time of birth and ossifies around the age of 4 years.1,2,7 The anterior arch ossifies around the age of 10 years from one or two ossification centres that form within the arch or by extension of the lateral masses.2,3 Failure of fusion results in a bipartite atlas with cartilage filled defects.

Clefts of the atlas are rare. When present, they exist most commonly in the posterior arch and less commonly in the anterior arch.1 Clefts of the posterior arch have been shown to be present in 4% of the population, while the prevalence of anomalies of the anterior arch is 0,1%.3,6,8 The prevalence of combined anterior and posterior defects is not known.

The case reported presented a diagnostic challenge. Rugby has a poor reputation with regard to cervical spine lesions knowing that the cervical spine is the most vulnerable to collision injury because it has greater mobility with smaller vertebrae, and less protective musculature compared with the rest of the spine.9 Together with other contact sports, rugby is the second most common cause for spinal cord injury in the first three decades of life.10 As in this case, the most frequent type of trauma is hyperflexion, which can cause posterior dislocation and fracture of the vertebral body. Extreme extension narrows the spinal cord, which can be harmed easily.9 Cervical dislocation and fracture are the most frequent mechanisms of spinal cord injury in sports trauma with catastrophic outcome.10

Plain radiographs showed atlantoaxial asymmetry and instability of the dens axis was suspected. CT scan was imperative in the diagnosis of bipartite atlas. The patient was protected with a stiff neck collar until the results of the CT scan were clear. A soft collar was given for comfort and was progressively discontinued and discarded after 1 week.

We were unable to identify any reports from the literature discussing the risk of instability or severe injuries in patients with asymptomatic clefts in the atlas. A loose posterior fragment may predispose for neurological symptoms but this was not present in our patient. Torg et al described relative and absolute contraindications to return to play after a spinal trauma.6,11 Atlantoaxial instability is rated as an absolute contraindication for contact and collision sports.11 Despite the fact that our patient had been a rugby player for several years and he had been subjected to several traumas in training and in competition without having major problems, we advised the patient to stop participating in contact sports. So far no problems have arose from his bipartite atlas. The question remains whether this anomaly is truly unstable or only mimicking instability. He will be followed regularly by radiographic examination, including flexion and extension views, to evaluate the evolution of this anomaly.

LEARNING POINTS

Cervical injuries are common in contact sports and trauma should be suspected until proven otherwise.

Although rare, the practitioner should remain aware of congenital causes.

In cases of diagnostic uncertainty more detailed imaging with CT is useful.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Osher SJ, Nasser NA. Coincidental finding of a bipartite atlas during assessment of a facial trauma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004; 42: 270–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hosalkar HS, Gerardi JA, Shaw BA. Combined asymptomatic congenital anterior and posterior deficiency of the atlas. Pediatr Radiol 2001; 31: 810–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park SY, Kang DH, Lee CH, et al. Combined congenital anterior and posterior midline cleft of the atlas associated with asymptomatic lateral atlantoaxial subluxation. Korean Neurosurg Soc 2006; 40: 44–6 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garg A, Gaikwad SB, Gupta V, et al. Bipartite atlas with os odontoideum: case report. Spine 2004; 29: E35–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osti M, Philipp H, Meusburger B, et al. Os odontoideum with bipartite atlas and segmental instability: a case report. Eur Spine J 2006; 15: 564–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klimo P, Jr, Blumenthal DT, Couldwell WT. Congenital partial aplasia of the posterior arch of the atlas causing myelopathy: case report and review of the literature. Spine 2003; 28: 224–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torriani M, Goes Lourenço JL. Agenesis of the posterior arch of the atlas. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo 2002; 57: 73–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Currarino G, Rollins N, Diehl JT. Congenital defects of the posterior arch of the atlas: a report of seven cases including an affected mother and son. AJNR 1994; 15: 249–54 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shelly MJ, Butler JS, Timlin M, et al. Spinal injuries in Irish rugby. JBJS 2006; 88B: 771–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantu RC, Mueller FO. Catastrophic spine injuries in American Football, 1977–2001. Neurosurgery 2003; 53: 358–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torg JS, Ramsey-Emrhein JA. Suggested management guidelines for participation in collision activities witch congenital, developmental or postinjury lesions involving the cervical spine. Med Sci Sports Exercise 1997; 29: 256–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]