Abstract

The objective of this work was to study the disposition kinetics of valine-valine–acyclovir (VVACV), a dipeptide ester prodrug of acyclovir following intravenous and oral administrations in rat. A validated LC-MS/MS analytical method was developed for the analysis VVACV, Valine-Acyclovir (VACV), and Acyclovir (ACV) using a linear Ion Trap Quadrupole. ACV was administered orally for comparison purpose. In the VVACV group, both blood and urine samples and in the ACV group only blood samples were collected. All the samples were analyzed using LC-MS/MS. The LLOQ for ACV, VACV, and VVACV were 10, 10, and 50 ng/ml, respectively. Relevant pharmacokinetic parameters were obtained by non-compartmental analyses of data with WinNonlin. Following i.v. administration of VVACV, AUC0−inf (min*µM) values for VVACV, VACV, and ACV were 55.06, 106, and 466.96, respectively. The AUC obtained after oral administration of ACV was 178.8. However, following oral administration of VVACV, AUC0−inf values for VACV and ACV were 89.28 and 810.77, respectively. Thus the exposure of ACV obtained following oral administration of VVACV was almost 6-fold higher than ACV. This preclinical pharmacokinetic data revealed that VVACV has certainly improved the oral bioavailability of ACV and is an effective prodrug for oral delivery of ACV.

Keywords: Acyclovir, dipeptide, prodrugs, metabolism, pharmacokinetics, renal excretion

Introduction

Acyclovir is clinically effective against herpes simplex (HSV), varicella-zoster and Epstain-Barr viral infections. HSV is one of the most common causes of genital ulcer disease worldwide. Acyclovir is the drug of choice approved for herpes simplex caused infections and is still extensively prescribed, especially in the treatment of immunocompetent patients with genital HSV disease (1–3). However, it possesses low bioavailability due to its poor solubility and permeation across gastrointestinal epithelium. Limited antiviral efficacy of ACV after oral administration is probably a consequence of its low bioavailability. Numerous prodrug and formulation approaches have been investigated to improve the solubility and oral bioavailability of acyclovir (4–7). Drug delivery by targeting nutrient transporters is an effective approach to improve absorption and tissue bioavailability. In this strategy the active drug is attached to promoiety, which is a substrate for a specific nutrient transport system. Such a strategy enables the transporter to recognize the conjugate as a nutrient and translocates it across the epithelial cell membrane. Valacyclovir (VACV) is a valine ester of acyclovir that has been reported to increase the oral bioavailability of acyclovir by 3–5-fold (2, 8, 9). This was due its recognition and translocation by peptide transporters (PEPT). In this study novel water-soluble dipeptide prodrugs of acyclovir were designed to target the PEPT on intestine (10).

VVACV is a dipeptide conjugate of acyclovir that has shown excellent in vitro antiviral activity against HSV1. It was found to be highly potent with an EC50 of 6.14 µM compared to 9.1 µM and 7.1 µM for VACV and ACV, respectively (11). VVACV exhibits excellent affinity towards peptide transporters (12) and displays high aqueous stability at pH ranges studied with no measurable degradation at pH 5.6, even after a week (13, 14). Excellent solubility and stability of VVACV presents an opportunity for developing stable aqueous formulations of ACV for oral administration in the treatment of herpes infections. Pharmacokinetics of VVACV after oral administration was studied earlier (14). However, its absolute bioavailability, urinary elimination kinetics, and metabolic disposition following intravenous administration were not previously reported.

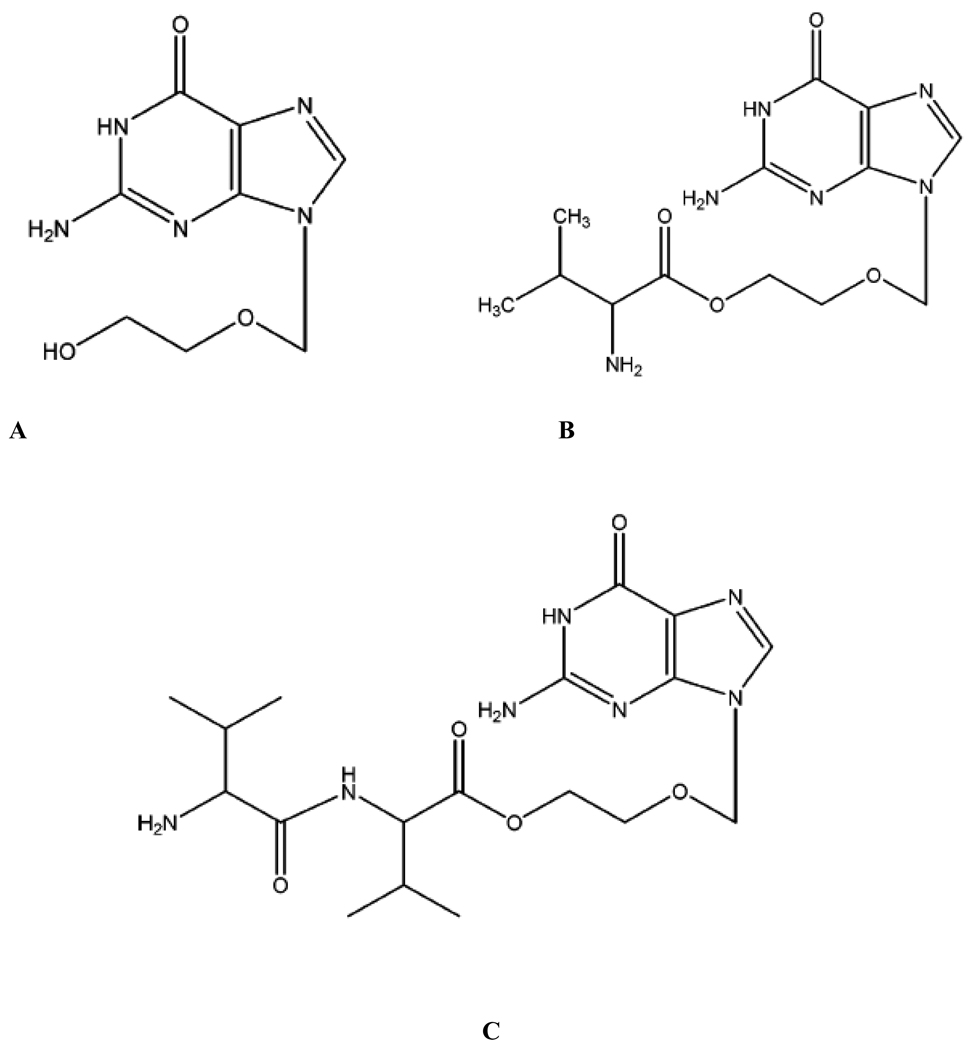

Following oral administration, VVACV will get hydrolyzed either completely or partially prior to entering systemic circulation. VVACV and its metabolites (VACV and ACV; Figure 1) once absorbed into systemic circulation will also be subjected to both metabolism by plasma esterases and elimination (renal) simultaneously. In order to understand the contribution of each pathway (metabolism and renal elimination) in overall elimination of VVACV and its metabolites both plasma and urinary pharmacokinetics need to be studied simultaneously. This would give insight into the prodrug metabolism, major metabolite(s) formed, elimination pathway, and renal elimination kinetics of intact prodrug as well as the metabolites. This knowledge can further be utilized to design novel prodrugs with optimum physicochemical properties and better pharmacokinetic profiles. This objective could be achieved by pharmacokinetic analysis of concentrations of VVACV and its metabolites in plasma and urine following oral administration. However, it would be difficult to obtain the complete in vivo metabolic profile of VVACV following oral administration due to its reported extensive pre-systemic metabolism. The plasma and urinary pharmacokinetic analysis after intravenous administration of VVACV will enable us to obtain the complete in vivo metabolic profile of the prodrug. The complete pharmacokinetic profile of VVACV would further enable us to evaluate its potential as a lead prodrug candidate for further studies.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures A) ACV B) VACV C) VVACV.

To study the pharmacokinetics of dipeptide conjugate, three species (dipeptide conjugate, amino acid metabolite, and the parent drug) need to be quantified in all the samples. In earlier studies HPLC–UV assay was utilized to analyze and measure the concentrations of the prodrugs and their metabolites. HPLC-UV methods are susceptible to interferences from co-eluting matrix constituents in biological samples. Quantitation of all three species in a single run requires longer runtimes with higher flow rates. Conjugation will also decrease the UV absorbance. Hence, in order to quantitate the prodrug and metabolites in plasma as well as urine, an assay with high sensitivity and specificity is warranted. LC-MS/MS assay has been widely utilized for pharmacokinetic studies due to its high specificity, sensitivity, and resolution. Moreover, shorter runtimes with lower flow rates makes this method more cost effective.

Hence the objectives of this study were:

to develop a highly sensitive LC-MS/MS assay for quantification of VVACV and its metabolites; and

to study the metabolic disposition and urinary elimination of VVACV following intravenous and oral administrations in rats.

Materials and methods

Materials

VACV was a gift from GlaxoSmithKline (Research Triangle Park, NC). VVACV was synthesized in our laboratory according to a standard established procedure (15). ACV was treated with NaOH in equimolar amounts to obtain the sodium salt. Heparin and heparin-coated tubes were obtained from Fisher scientific. Saline was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma chemical company and were used as received without further purification.

Animals

Jugular vein cannulated male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing between 200–250 g were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Animal care and treatment employed in this research were in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the National Institutes of Health.

Solubility studies

Aqueous solubility studies of VVACV were carried out in deionized water (pH 5.5). Excess amount of the drug was added to 500 µl water in glass vials and placed in a shaking water bath at 25°C and 60 rpm for 24 h. Then the solutions were centrifuged at 12,500 rpm for 10 min and the supernatant was filtered through 0.45 µm Nalgene syringe filter membrane. Solubility studies were carried out in duplicate. The samples were diluted appropriately and analyzed for VVACV by LC-MS/MS

Animal studies

Animals were given ACV-sodium and VVACV molar dose equivalent to 20 mg/kg of ACV orally by gavage and 10 mg/kg of VVACV intravenously as a bolus via jugular vein cannula (3–4 animals per route). For oral studies, animals were fasted overnight (10–12 h) with free access to water. Before the experiment, rats were transferred into metabolic cages to facilitate urine collection. Blank urine was collected and stored at −80°C before administering the drug. Urine was collected only for the VVACV group. Freshly prepared drug solutions were given by oral gavage (0.8 ml). For intravenous dosing 200 µl of drug in sterilized saline followed by 200 µl of blank sterile heparanized saline were administered via jugular vein cannula. Blood samples (200 µl) were collected from the jugular vein into heparin-coated tubes and replaced with the same volume of heparanized saline (100 U/ml) at pre-determined time intervals over a period of 8 h. Blood was immediately centrifuged (7500 g for 5 min) to separate the plasma which was stored at −80°C until further analysis. Urine samples were collected at regular intervals depending on the frequency of urination up to 12 h. The volume of urine sample at each time point was measured and recorded. About 150 µl of urine sample was stored in −80°C until further analysis. At the end of an experiment, animals were euthanized with 10 mg per 100 g body weight of sodium pentobarbital administered through jugular vein cannula.

Sample preparation

Samples were purified by protein precipitation method. Ganciclovir (GCV) was used as an internal standard. Plasma and urine samples were thawed at room temperature. Five microliters of 10 µg/ml GCV (500 ng/ml) and 200 µl of acetonitrile were added to 100 µl of sample. The mixture was vortexed vigorously for 2 min and allowed to rest for 10 min at room temperature prior to centrifugation. Samples were centrifuged at 5000 g for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected. The solvent was evaporated to dryness with a Speedvac (SAVANT Instruments, Inc., Holbrook, NY). The dry residue was reconstituted in 100 µl water and further centrifuged (5000 g, 4 min). The supernatant was analyzed using LC-MS/MS. Calibration standards for ACV, VACV, and VVACV were prepared by spiking the known analyte concentrations to blank plasma and urine. The standards were also subjected to identical treatment as samples and a standard curve was obtained.

LC/MS/MS

A linear Ion Trap Quadrople LC/MS/MS mass spectrometer (AB Sciex instruments) with electrospray ionization on Turbo Spray ion source (API 2000; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) coupled to an Agilent 1100 binary pump, degasser, and an autosampler was selected for analysis. Initially, ACV, VACV, and VVACV solutions were infused at 10 µl/min and the masses of parent ion (Q1) and their respective major fragment (Q3) were obtained. Data was collected in multiple reactions monitoring (MRM) mode. The ion source parameters including declustering potential (DP), collision energy (CE), entrance potential (EP), and collision cell exit potential (CXP) 4V were 36 V, 18 eV, 6 V, and 4 V, respectively. The gas parameters were nebulizer gas at 10 (arbitrary units), the curtain gas was at 8 and the collision gas was at 4. The ionization voltage and source temperature were maintained at 4500 V and 500°C, respectively. The compounds were separated with Grace Alltima C8 (150 mm × 2.1 mm, 5 µ pore size) column attached to a guard column. The flow rate was 0.15 ml/min.

The mass/charge (m/z) of parent ion (Q1) and its major fragment (Q3) are:

ACV: 226.10/152.10;

VACV: 325.10/152.10; and

VVACV: 424.20/174.20.

VACV and its metabolites were quantified by the ratio of analyte to the internal standard (ganciclovir). The method was validated using parameters such as range, selectivity, precision, and accuracy. Accuracy was determined by checking the closeness of mean test results obtained by the method to the true concentration of the analyte. For precision, relative standard deviation was measured after replicate analyses of standards with known concentrations. LLOQ was calculated for each species and the precision was also determined at that concentration.

Pharmacokinetic data analysis

All the relevant pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated by non-compartmental analyses of plasma concentration—time curves with a pharmacokinetic software package WinNonlin, version 5.0 (Pharsight, Mountain View, CA). Cmax, Tmax, Clast, and Tlast values were obtained from the log plasma concentration–time curves. Concentration at zero time point (C0) after i.v. administration was obtained by extrapolation of plasma–time curve of VVACV and its metabolites to zero time point. The slopes of the terminal phase of plasma profiles were estimated by log-linear regression and the terminal rate constant (λz) was derived from the slope of terminal elimination phase. Area under the curve from zero to the last measurable concentration (AUC0−t) was estimated by the linear trapezoidal method. AUC from time zero to infinity (AUC0−inf) was calculated as

| (1) |

Ct is the last quantitable concentration at time t and λz is the first-order terminal elimination rate constant.

Total body clearance (ClT) and volume of distribution (Vz) after i.v. bolus administration were calculated as a ratio of dose/AUC and ClT/λz, respectively. Mean residence time (MRT) was obtained from the ratio of AUMC to AUC, where AUMC denotes the area under the 1st moment curve.

Urinary data

Urinary elimination curves and elimination rate constants were obtained by WinNonlin, version 2.1 (Pharsight, Mountain View, CA). The data was plotted according to the excretion rate method. The elimination rate constant (k) was obtained from the slope of the plot. Amount recovered was obtained from cumulative amounts of drug eliminated through urine during the entire study period. Renal elimination rate constant (ke) was obtained from the Y-intercept of rate plot. Percent of dose eliminated, renal clearance (Clr), non-renal clearance (Clnr), metabolic rate constant (km) and fraction of VVACV metabolized (Fm) were calculated according to equations listed below.

| (2) |

where Au0−12 is the cumulative amount of drug/prodrug eliminated into urine over a period of 12 h

| (3) |

where AUC0−t = Plasma AUC;

| (4) |

where ClT = Total body clearance;

| (5) |

| (6) |

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise indicated, all data were presented as mean ± SD. Student’s t-test was used to determine the statistical difference between two sets. p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

LC-MS/MS

A highly sensitive and robust LC-MS/MS method was developed. It is highly specific as only the ions of interest are monitored. The LLOQ for ACV, VACV, and VVACV were 10, 10, and 50 ng/ml, respectively. All the validation parameters have been tabulated (Table 1). The mean value obtained for accuracy measurements was within 15% of the actual value. Relative standard deviation (RSD) was less than 3% for all the concentrations examined.

Table 1.

Validation parameters for LC-MS/MS analysis of VVACV, VACV and ACV

| Parameter | ACV | VACV | VVACV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 10 – 2500ng | 10 – 2500 ng | 50 – 5000ng |

| Linearity (R2) | 0.9988 | 0.9997 | 0.9998 |

| LLOQ | 10ng/ml | 10ng/ml | 50ng/ml |

| Precision (RSD) | 2.28% | 5.04% | 2.8% |

| Precision at LLOQ | 1.81% | 4.66% | 5.59% |

Solubility studies

The aqueous solubility of VVACV was found to be 202 ± 15 mg/ml. This was much higher than that reported for ACV (2.5 mg/ml).

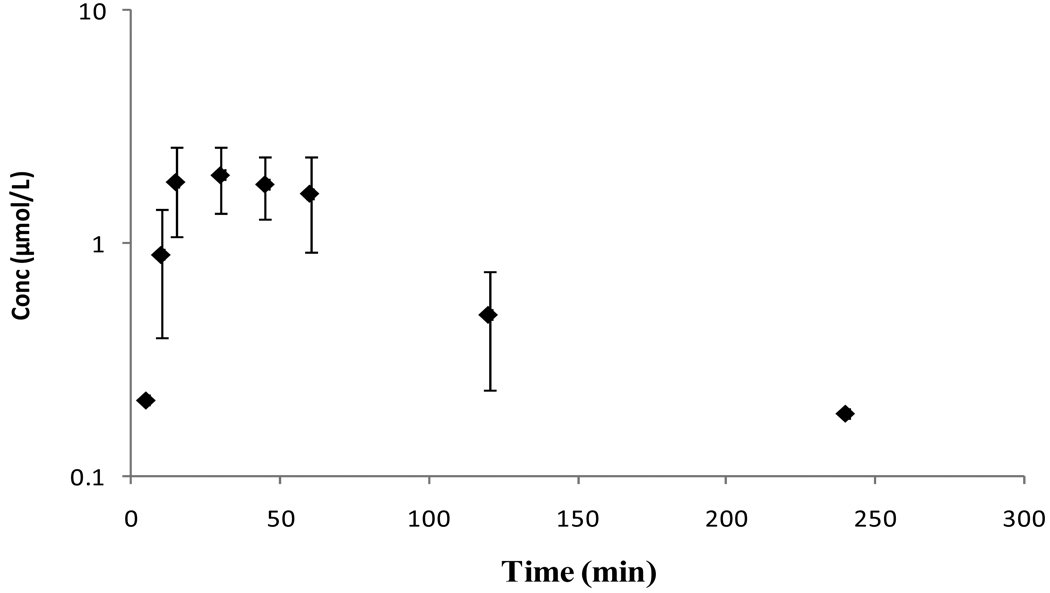

Pharmacokinetics of ACV following oral administration of sodium salt of ACV

Mean plasma concentration–time profile of ACV following oral administration of sodium salt of ACV is shown in Figure 2. Relevant pharmacokinetic parameters are tabulated in Table 2. Peak plasma concentrations were reached at 20 min post-oral dosing. The drug was observed in the plasma till 360 min. After reaching the peak concentrations (Cmax), the plasma concentration declined biexponentially with an initial rapid distribution followed by a prolonged elimination phase.

Figure 2.

Mean plasma concentration – time profiles of ACV following oral administration of ACV in rats. Each value is represented as mean ± SD (n=3–4).

Table 2.

Plasma pharmacokinetic parameters of ACV following oral administration of sodium salt of ACV in rats.

| pK parameter | ACV |

|---|---|

| Cmax (µM) | 2.19 ± 0.62 |

| Tmax (min) | 26.2 ± 14.4 |

| AUC0−t (min*µM) | 155.6 ± 35.4 |

| AUC0−inf (min*µM) | 178.8 ± 34.02 |

| λz (min−1) | 0.02 ± 0.002 |

(Values are represented as mean ± S.D, n=3–4)

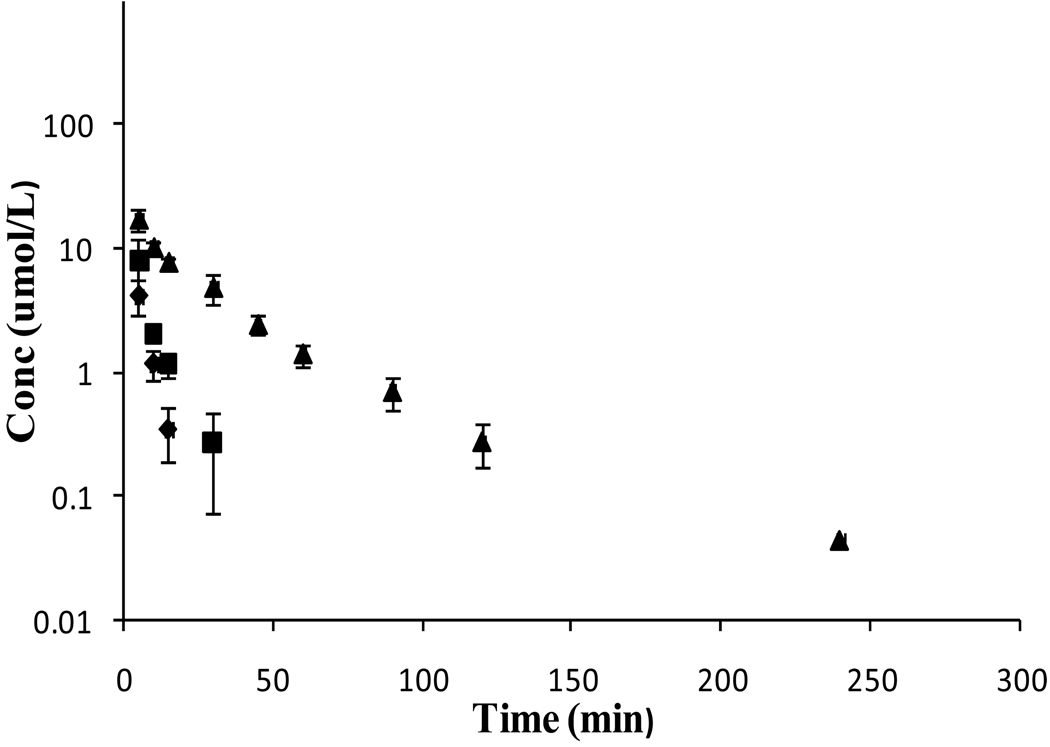

Plasma and urinary pharmacokinetics following i.v. administration of VVACV

Following i.v. administration of 10 mg/kg of VVACV, all the three species VVACV, VACV intermediate, and the parent drug ACV were observed in plasma as well as urine. The mean plasma concentration–time profiles are shown in Figure 3. Plasma levels of VVACV, VACV, and ACV were observed till 15, 30, and 120 min, respectively. Plasma concentrations of all three species declined biexponentially. Two phases, initial rapid distribution followed by prolonged elimination, were distinct in the plasma–time curve of ACV. The pertinent pharmacokinetic parameters for VVACV, VACV, and ACV were tabulated (Table 3). Cmax and AUC values were in the order of ACV > VACV > VVACV. The calculated ClT values for VVACV and VACV were significantly higher than of ACV, as it represents total elimination (metabolism and renal excretion).

Figure 3.

Mean plasma concentration – time profiles of VVACV, regenerated VACV and ACV following i.v. administration of VVACV in rats. (◆- VVACV, ■ – VACV, ▲- ACV).

Table 3.

Plasma pharmacokinetic parameters of VVACV and the generated VACV and ACV following i.v. administration of VVACV in rats.

| pK parameter | VVACV | VACV | ACV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co (µM) | 11.2 ± 5.2 | 19.09 ± 5.15 | 23.1 ± 1.12 |

| Clast (µM) | 0.35 ± 0.16 | 0.27 ± 0.19 | 0.27 ± 0.12 |

| Tlast (min) | 15 | 30 | 240 |

| AUC0−t (min* µM) | 53.1 ± 13.4 | 102.8 ± 16.1 | 458.8 ± 56.3 |

| AUC0−inf (min* µM) | 55.1 ± 13.2 | 106 ± 12.6 | 467 ± 53.2 |

| AUC0−inf/D | 2.88 ± 0.69 | 5.56 ± 0.66 | 24.5 ± 2.8 |

| Vz (L/kg) | 1.66 ± 0.66 | 0.98 ± 0.54 | 1.69 ± 0.64 |

| Cl (ml/min/kg) | 358.0 ± 77.8 | 181.2 ± 23.4 | 41.1 ± 4.7 |

| MRT0−inf(min) | 3.35 ± 1.34 | 3.83 ± 1.40 | 26.24 ± 3.91 |

| λz (min−1) | 0.25 ± 0.07 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.03 ± 0.008 |

(Values are represented as mean ± S.D, n=4)

All the urinary elimination kinetic parameters are tabulated (Table 4). Mean cumulative urinary excretion was 91.11% of the total dose. Systemic elimination rate constants (k) for all the three species do not differ significantly from each other. However, the ke and km significantly differ. Fraction of VVACV metabolized was 0.68 ± 0.06. Hence, ~ 68% of administered VVACV was metabolized in the body to VACV and ACV with the remaining 32% being eliminated in urine as intact dipeptide.

Table 4.

Urinary pharmacokinetic parameters of VVACV and the generated VACV and ACV following i.v. administration of VVACV in rats.

| pK parameter | VVACV | VACV | ACV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of dose recovered (%) | 31.81 ± 6.22 | 10.72 ± 1.99 | 48.57 ± 16.47 |

| Clr (ml/min/kg) | 124.19 ± 48 | 18.61 ± 1.94 | 19.94 ± 7.21 |

| Clnr (ml/min/kg) | 233.83 ± 41.69 | 162.58 ± 25.25 | 21.2 ± 6.16 |

| k (hr−1) | 1.73 ± 0.22 | 1.6 ± 0.61 | 1.72 ± 0.51 |

| ke (hr−1) | 0.61 ± 0.30 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 1.16 ± 0.52 |

| km (hr−1) | 1.11 ± 0.12 | 1.40 ± 0.57 | 0.55 ± 0.24 |

(Values are represented as mean ± S.D, n=4)

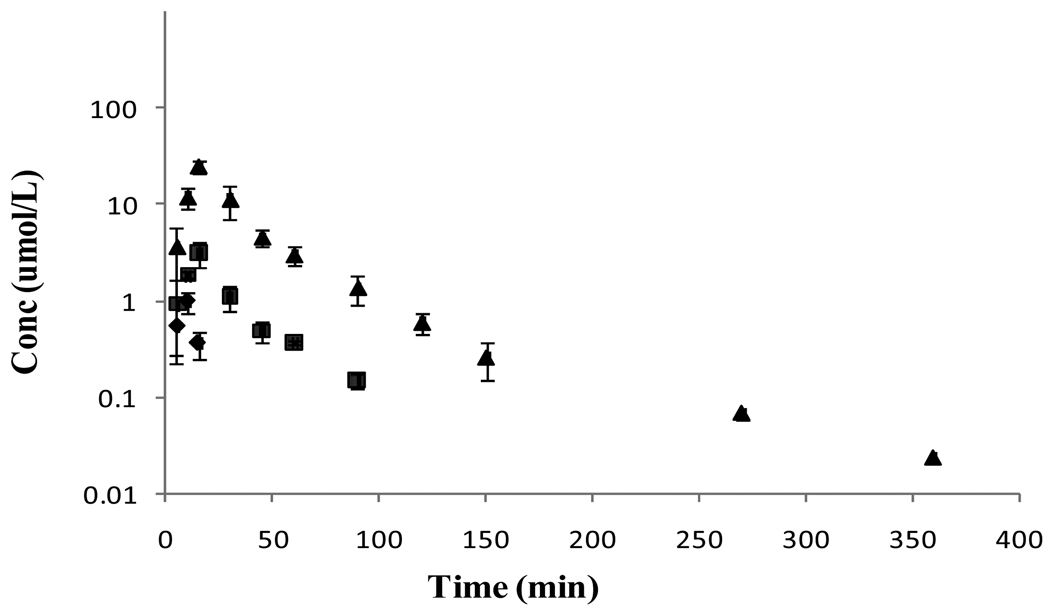

Plasma and urinary pharmacokinetics following oral administration of VVACV

As observed after i.v. administration all the three species VVACV, VACV, and ACV appeared in the circulation following oral administration of VVACV (Figure 4). However, the concentration of VVACV was very low and was observed only for the first few time points. After the peak plasma concentration was reached (Tmax) the concentrations of both VACV and ACV declined rapidly with two distinct phases, a rapid initial distribution and a prolonged terminal elimination phase. Plasma pharmacokinetic parameters of regenerated VACV and ACV are tabulated in Table 5. In the urinary data analysis, no absorption phase was observed due to the rapid absorption and metabolism of VVACV and its metabolites. The absorption phase was completed within 15 min, while the first time interval of urine collection was 0–2 h. In urine, no VVACV was observed and VACV was detected only in the first collection time interval. ACV was detected throughout the collection period. The mean urinary excretion of the total drug in the urine was 37% of the dose.

Figure 4.

Mean plasma concentration – time profiles of VVACV and the regenerated VACV and ACV following oral dosing of VVACV in rats. (◆- VVACV, ■ – VACV, ▲- ACV).

Table 5.

Plasma pharmacokinetic parameters of VVACV and the generated VACV and ACV following oral administration of VVACV in rats.

| pK parameter | VACV | ACV |

|---|---|---|

| Tmax (min) | 15 | 15 |

| Cmax (µM) | 3.14 ± 0.28 | 25.49 ± 1.71 |

| AUC0−t (Min*µM) | 82.51 ± 6.81 | 808.56 ± 72.06 |

| AUC0−inf (min*µM) | 89.28 ± 4.78 | 810.77 ± 73.39 |

| λz (min−1) | 0.03 ± 0.008 | 0.01 ± 0.008 |

(Values are represented as mean ± S.D, n=4)

Discussion

Peptide transporters (PEPT) have gained significance in drug delivery due to their broad substrate specificity and high capacity. In order to improve gastrointestinal absorption and oral bioavailability of acyclovir, dipeptide prodrugs of acyclovir were designed to target PEPT expressed on the intestinal mucosa. VVACV is such a dipeptide prodrug that it has shown excellent in vitro anti-viral activity against HSV-1 in human fibroblast foreskin cells and in vivo anti-viral activity against HSV-1 in rabbit epithelial and stromal keratitis models (11, 13). In this study, absolute bioavailability, in vivo metabolism, and urinary excretion of VVACV were studied following i.v. and oral administrations in rats. The chemical structures of VVACV, VACV, and ACV are shown in Figure 1. Following i.v. administration, VVACV was metabolized to VACV and ACV very rapidly in plasma as all the three species were observed in plasma as well as urine from first sampling time point (Figure 3). Hydrolytic mechanism of VVACV was studied previously (11, 13). The peptidases hydrolyze the peptide bond of VVACV and generate VACV, which is further hydrolyzed by esterases to generate the parent drug ACV. Direct metabolic conversion of VVACV to ACV is very minimal. Very high Vz values of all three species compared to the blood volume in rats suggests their extensive distribution throughout the body. Two main routes of elimination of drug/prodrug from plasma are enzyme hydrolysis and renal excretion. Since VVACV and VACV undergo rapid enzymatic hydrolysis, significantly higher non-renal clearance values (Clnr) and metabolic rate constants (Km) are observed in comparison to generated acyclovir. ClT, Clnr, and Km values are in the order of VVACV > VACV > ACV (Tables 3 and 4). Renal clearance (Clr) values are in the order of VVACV > ACV ≈ VACV (Table 4). The Clnr of VACV is almost 8-times higher than its Clr, clearly suggesting that VACV disappear from the plasma primarily by metabolism, probably via plasma esterases. There is no significant difference between Clnr and Clr for ACV. Thus, ACV appears to be eliminated both by metabolism and renal excretion. Even though Clnr of VVACV is significantly higher than its corresponding Clr, it seems to be eliminated both by metabolism and renal excretion, with metabolism being the primary route. These observations are further confirmed by the amount of dose obtained in the urine. About 91% of the administered dose was recovered in urine. Of that 31.81% was eliminated as intact dipeptide VVACV. Percent of dose obtained as VACV and ACV in urine are 10.72 and 48.57, respectively (Table 4). Mechanism of renal elimination can be further delineated by comparing Clr with creatinine clearance (Clcr) in rat. Reported Clcr in rat is 7–18 ml/min/kg (16). The observed Clr of VVACV is 124.19 ± 48 ml/min/kg. This value is significantly higher than Clcr, indicating that the renal elimination of VVACV involves both glomerular filtration and active secretion. Clr values of generated VACV and ACV are nearly equal to Clcr. Thus, glomerular filtration alone appears to be the major route of renal elimination for VACV and ACV. Active tubular secretion of VVACV might be due to its transport by PEPT expressed on the nephron of rat kidney. The presence of functionally active PEPT on brush border membrane of renal epithelial cells as well as proximal and distal tubules of nephron was already established (17–21). Being recognized by PEPT, VACV is also expected to get partly eliminated by tubular secretion. However, the Clr of VACV indicates that it was eliminated primarily by glomerular filtration, suggesting that VACV might not be a preferred substrate for PEPT expressed in kidney. It could be also due to low concentrations of intact VACV available, as it is highly subjected to metabolism which is evident by amount of VACV (10.72%) obtained in urine. About 68% of VVACV dose was metabolized into VACV and ACV and the remaining 32% of the dose was eliminated as intact dipeptide conjugate in urine (Table 4). In other words, ~ 32% of the administered dose was eliminated before it generates the parent acyclovir upon hydrolysis. Thus, renal elimination along with metabolism plays a significant role in determining the overall amount of parent drug available (generated from prodrug) to exert its therapeutic action. This observation can further influence the therapeutic efficacy of the prodrug. These results can become even more important when the prodrugs are to be delivered intravenously to target the nutrient transporters expressed on the blood ocular or blood–brain barriers to improve drug absorption into eye and brain. In such cases the availability of intact prodrug and its ability to generate the drug are equally important.

Orally administered VVACV exhibited excellent oral absorption, rapid distribution, and essentially complete biotransformation. All three species are observed from the first sampling time point, 5 min (Figure 4). VVACV disappeared completely from plasma after 15 min. Very low concentrations of VVACV and predominance of ACV in plasma indicates presystemic metabolism of VVACV and VACV followed by rapid absorption of all three species (Table 5). As observed after i.v. dosing, plasma concentrations of ACV and VACV declined in a biexponential manner and are observed till 360 and 90 min, respectively. About 37% of the administered dose is recovered in urine and 99% of that fraction is ACV, indicating the complete biotransformation of VVACV and VACV to ACV. A significant fraction of the dose is eliminated in the first 3 h post-dosing. In comparison with the administration of sodium salt of ACV, the AUC of ACV resulted after administration of VVACV was almost 5-fold higher, indicating its improved bioavailability.

In summary, VVACV, a prodrug of acyclovir with high aqueous solubility and stability, has demonstrated a favorable pharmacokinetic profile following oral administration in rats. The prodrug had undergone complete biotransformation into the parent dug acyclovir. More importantly, the prodrug provided enhanced the oral bioavailability of ACV. Prodrug kinetics following i.v. administration had enabled us to explore the metabolism and elimination pathway of VVACV and its metabolites. This knowledge can further assist in designing more effective prodrugs with even better pharmacokinetic parameters

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Swapan K. Samanta for synthesizing VVACV. We would like to thank GlaxoSmithKline for the generous supply of Valacyclovir. This work was supported by NIH grants RO1 EY09171 -14 and RO1 EY10659 -12.

References

- 1.Apoola A, Radcliffe K. Antiviral treatment of genital herpes. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15:429–433. doi: 10.1258/0956462041211153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perry CM, Faulds D, Valaciclovir A review of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy in herpesvirus infections. Drugs. 1996;52:754–772. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199652050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393–1397. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.11.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Attia IA, El-Gizawy SA, Fouda MA, Donia AM. Influence of a niosomal formulation on the oral bioavailability of acyclovir in rabbits. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2007;8:E106. doi: 10.1208/pt0804106. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmberger TF, Hombach J, Bernkop-Schnurch A. Thiolated chitosan: development and in vitro evaluation of an oral delivery system for acyclovir. Int J Pharm. 2008;348:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.07.004. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel D, Sawant KK. Oral bioavailability enhancement of acyclovir by self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems (SMEDDS) Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2007;33:1318–1326. doi: 10.1080/03639040701385527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purifoy DJ, Beauchamp LM, de Miranda P, Ertl P, Lacey S, Roberts G, Rahim SG, Darby G, Krenitsky TA, Powell KL. Review of research leading to new anti-herpesvirus agents in clinical development: valaciclovir hydrochloride (256U, the L-valyl ester of acyclovir) and 882C, a specific agent for varicella zoster virus. J Med Virol. 1993 Suppl 1:139–145. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890410527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granero GE, Amidon GL. Stability of valacyclovir: implications for its oral bioavailability. Int J Pharm. 2006;317:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobson MA. Valaciclovir (BW256U87): the L-valyl ester of acyclovir. J Med Virol. 1993 Suppl 1:150–153. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890410529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soul-Lawton J, Seaber E, On N, Wootton R, Rolan P, Posner J. Absolute bioavailability and metabolic disposition of valaciclovir, the L-valyl ester of acyclovir, following oral administration to humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2759–2276. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anand BS, Hill JM, Dey S, Maruyama K, Bhattacharjee PS, Myles ME, Nashed YE, Mitra AK. In vivo antiviral efficacy of a dipeptide acyclovir prodrug, val-val-acyclovir, against HSV-1 epithelial and stromal keratitis in the rabbit eye model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2529–2534. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anand BS, Patel J, Mitra AK. Interactions of the dipeptide ester prodrugs of acyclovir with the intestinal oligopeptide transporter: competitive inhibition of glycylsarcosine transport in human intestinal cell line-Caco-2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:781–791. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.044313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anand B, Nashed Y, Mitra A. Novel dipeptide prodrugs of acyclovir for ocular herpes infections: bioreversion, antiviral activity and transport across rabbit cornea. Curr Eye Res. 2003;26:151–163. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.26.3.151.14893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anand BS, Katragadda S, Mitra AK. Pharmacokinetics of novel dipeptide ester prodrugs of acyclovir after oral administration: intestinal absorption and liver metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:659–667. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.069997. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nashed YE, Mitra AK. Synthesis and characterization of novel dipeptide ester prodrugs of acyclovir. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2003;59:2033–2039. doi: 10.1016/s1386-1425(03)00007-6. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krasny HC, Beauchamp L, Krenitsky TA, de Miranda P. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of a double prodrug of ganciclovir in the rat and monkey. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:1242–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daniel H, Kottra G. The proton oligopeptide cotransporter family SLC15 in physiology and pharmacology. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:610–618. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izzedine H, Launay-Vacher V, Deray G. Renal tubular transporters and antiviral drugs: an update. AIDS. 2005;19:455–462. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000162333.35686.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Launay-Vacher V, Izzedine H, Karie S, Hulot JS, Baumelou A, Deray G. Renal tubular drug transporters. Nephron Physiol. 2006;103:97–106. doi: 10.1159/000092212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen H, Smith DE, Yang T, Huang YG, Schnermann JB, Brosius FC., 3rd Localization of PEPT1 and PEPT2 proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter mRNA and protein in rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:F658–F665. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.5.F658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith DE, Pavlova A, Berger UV, Hediger MA, Yang T, Huang YG, Schnermann JB. Tubular localization and tissue distribution of peptide transporters in rat kidney. Pharm Res. 1998;15:1244–1249. doi: 10.1023/a:1011996009332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]