Abstract

While selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, namely cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX 2) inhibitors, are known to be associated with acute myocardial infarction, little is known about the cardiovascular safety of the non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. We report the case of a 44-year-old man who developed anaphylactic reaction and acute inferior myocardial infarction following ingestion of a non-selective anti-inflammatory drug, diclofenac sodium. Coronary angiography revealed a large thrombus in the right coronary artery which was partially removed by intracoronary catheter aspiration. Complete resolution of the remaining thrombus was achieved after treatment with an oral anticoagulant.

Background

There is growing concern about an increased risk of thrombotic events with the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), in particular the selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX 2) inhibitors. Increasing evidence shows that these thrombotic complications may also occur with the use of non-selective NSAIDs.1 We report a case of acute myocardial infarction following ingestion of diclofenac sodium where coronary angiography confirmed the presence of intracoronary thrombus.

Case presentation

A 44-year-old man presented to the emergency department with an acute onset of central chest pain associated with vomiting, sweating, generalised urticaric rash, difficulty breathing and wheezing 1 h following ingestion of diclofenac sodium. He took a total of two tablets of 50 mg diclofenac sodium, each one 4 hours apart, for his headache. He was under follow-up of a respiratory physician for his bronchial asthma and chronic allergic rhinitis. He did not have significant risk factors for coronary artery disease. In the past, he was not known to have any drug allergies and had never ingested diclofenac sodium. Clinical examination revealed: temperature 37°C, blood pressure 70/43 mm Hg, pulse 85 per min regular, and oxygen saturation 83% on room air. There was urticarial rash seen all over his body and ronchi were heard on auscultation of the chest.

Investigations

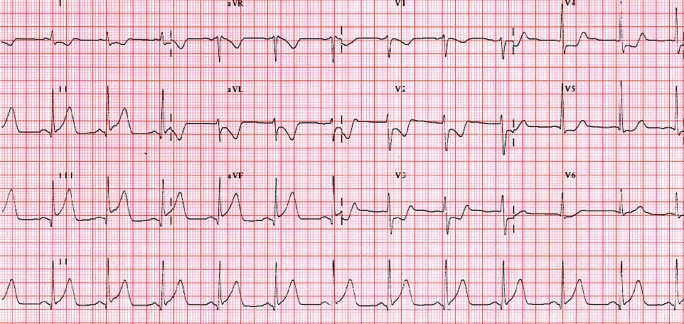

Twelve lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed raised ST segments in leads II, III and aVF, and reciprocal changes were seen in leads V2, V3, V4, I and aVL (fig 1). The diagnosis of anaphylactic reaction and coronary vasospasm secondary to diclofenac sodium was considered. The patient was then treated with intravenous fluid resuscitation, epinephrine, hydrocortisone, chlorpheniramine, and heparin. Subsequently, his condition normalised and repeat ECG showed return of the ST segment to the baseline. Initial laboratory investigations revealed normal cardiac enzymes, troponin, blood sugar and lipid profile.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram showing ST segment elevation in leads II, III and aVF, and reciprocal changes in leads V2, V3, V4, I and aVL.

The following day a repeat ECG showed recurrence of ST segment elevation in the inferior leads. The patient did not report any chest pain or hypersensitivity symptoms, and the physical examination was unremarkable. Cardiac enzymes showed creatinine kinase (CK) of 1015 U/l (normal range (NR) 24–204 U/l), CK-MB of 143 ng/ml (normal <5.0 ng/ml), and troponin T of 0.31 μg/l (NR 0–0.10 μg/l). Peripheral blood film did not show any evidence of eosinophilia. At this stage, aspirin was given as he was suspected to have de novo myocardial infarction. Unfortunately, he developed mild allergic reaction shortly after aspirin ingestion. Aspirin was discontinued and the patient was treated accordingly with subsequent improvement of his condition. Echocardiography revealed a structurally normal heart.

Treatment

Urgent coronary angiography was performed and showed normal coronaries; however, a large thrombus was seen in the lumen of mid segment of the right coronary artery (fig 2). Multiple attempts of intracoronary thrombus aspirations were only able to remove a small amount of blood clot (fig 3). Because a large burden of thrombus was still present, continuous intravenous glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antiplatelet receptor inhibitor (abciximab) was given followed by subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin for 5 days. A repeat coronary angiogram performed 5 days later revealed 50% reduction in the amount of blood clot seen. The patient was discharged well with the anticoagulant warfarin (target INR of between 2–3), for treatment of the remaining thrombus, and an antiplatelet agent (clopidogrel). He was also given a medical alert card for avoidance of NSAIDs.

Figure 2.

Coronary angiography showing thrombus in the middle segment of right coronary artery.

Figure 3.

Thrombus obtained from intracoronary catheter aspiration.

Outcome and follow-up

An elective coronary angiogram performed 1 month later revealed complete clearance of the clot (fig 4). Nevertheless, a closer look at the previously sited thrombus by using intravenous ultrasound showed the presence of underlying mild atheromatous plaque. Warfarin was discontinued and the patient was prescribed clopidogrel and a statin for the mild coronary artery disease.

Figure 4.

Repeat angiography after treatment with oral anticoagulation, showing complete resolution of the thrombus in the right coronary artery.

Discussion

Although acute myocardial infarction has been shown to be associated with the use of specific COX 2 inhibitors, its association with non-specific COX inhibitors is less apparent.2 Traditional NSAIDs, including diclofenac sodium, are among the most commonly prescribed analgesics over the counter. Diclofenac sodium is a non-selective COX inhibitor which acts by inhibiting both COX 1 and COX 2, resulting in anti-inflammation, analgesia and antipyresis.3 Previous reports have demonstrated the increased risk of myocardial infarction with the use of conventional NSAIDs including diclofenac sodium compared with non-users.3,4 As diclofenac is similar to celecoxib (a COX 2 inhibitor) in terms of COX 2 blocking effects, it could theoretically increase the risk of thrombotic events like other COX 2 inhibitors.

Our patient developed an anaphylactic reaction as well as an acute inferior myocardial infarction following ingestion of diclofenac sodium. Unfortunately, he developed an allergic reaction to aspirin too, which indicates his sensitivity to NSAIDs as a whole. Hypersensitivity to NSAIDs is frequently a result of a non-immunological mechanism, particularly in the presence of asthma.5,6 In our patient, this can be explained to some extent by the absence of eosinophilia, which is frequently present in allergic inflammation such as in Kounis syndrome.7 It is our opinion that the anaphylactic reaction caused coronary vasoconstriction. However, the visualisation of atheroma on intravascular ultrasound and thrombus at angiography raises the possibility of concomitant plaque rupture. Hence, myocardial infarction may have developed as a consequence of both allergic reaction and the prothrombotic effect of cyclo-oxygenase inhibition.

There are several case reports on adverse reactions to diclofenac sodium and coronary events reported in the literature. Mori et al reported a case of allergic vasospastic angina due to diclofenac sodium, although neither myocardial necrosis nor abnormal coronary arteries were demonstrated.8 In the case reported by Gluvic and colleagues, a patient developed acute myocardial infarction secondary to hypersensitivity reaction to intravenous diclofenac,9 but there was a lack of angiography to visualise any coronary abnormalities. Sim recently reported a patient with myocardial infarction triggered by an allergic reaction to an NSAID,10 but coronary thrombus was not identified angiographically. In contrast to these case reports, our patient demonstrated a complete spectrum of myocardial infarction together with angiographically proven coronary thrombus as a result of pre-existing atheroma combined with the adverse drug reaction.

Learning points

Our case suggests the possible risk of cardiovascular thrombotic events associated with the use of conventional COX inhibitors.

Coronary thrombus may develop as a result of exaggerated thrombotic response to ruptured atherosclerotic plaque which may be precipitated by NSAIDs.

In selected cases, anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist may be a reasonable alternative when there is failure of other modalities to remove the thrombus.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent was obtained for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jick H, Kaye JA, Russmann S, et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and acute myocardial infarction in patients with no major risk factors. Pharmacotherapy 2006; 26: 1379–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh G, Wu O, Langhorne P, et al. Risk of acute myocardial infarction with nonselective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a meta-analysis. Arthrit Res Ther 2006; 8: R153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kearney PM, Bainqent C, Godwin J, et al. Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2006; 332: 1302–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fosbøl EL, Gislason GH, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction and death associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) among healthy individuals: a nationwide cohort study. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009; 85: 190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leimgruber A. Allergic reactions to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Revue Médicale Suisse 2008; 4: 100–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matucci A, Rossi O, Cecchi L. Coronary vasospasm during an acute allergic reaction. Allergy 2002; 57: 867–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kounis N. Kounis syndrome (allergic angina and allergic myocardial infarction): a natural paradigm? Int J Cardiol 2006; 110: 7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mori E, Ikeda H, Haramaki N, et al. Vasospastic angina induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin Cardiol 1997; 20: 656–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gluvic ZM, Putnikovic B, Panic M, et al. Acute coronary syndrome in diclofenac sodium-induced type 1 hypersensitivity reaction: Kounis syndrome. Malta Med J 2007; 19: 1–3 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sim TB. NSAID-induced anaphylaxis precipitating acute coronary vasospasm. Eur J Emerg Med 2008; 15: 48–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]