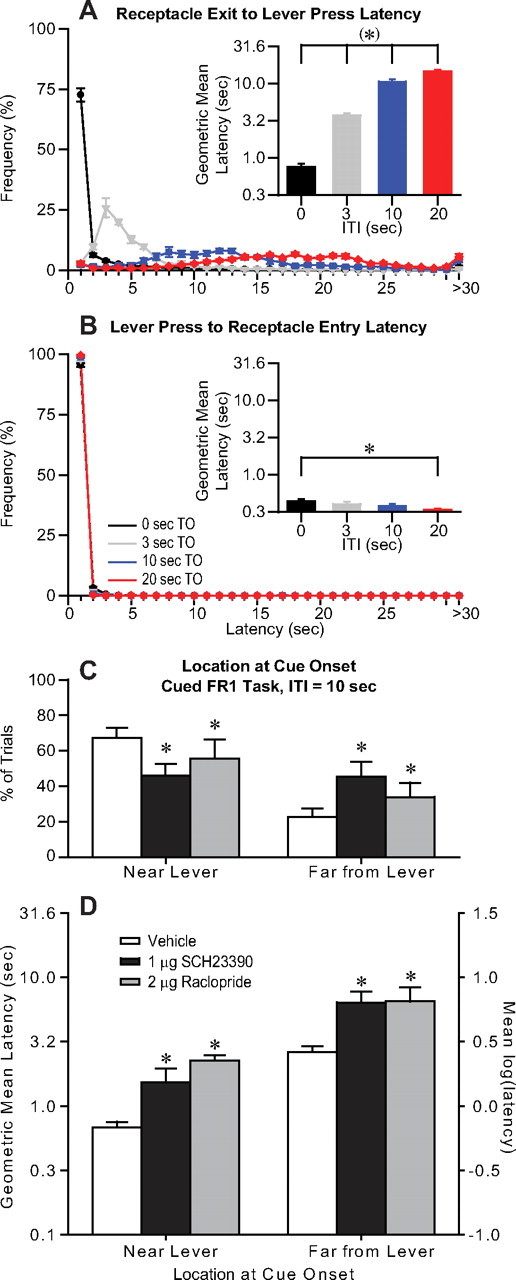

Figure 2.

Animals leave the lever and receptacle in long but not short-ITI tasks. A, Distributions of latencies to press the lever after reward consumption during vehicle injections (core, shell, and core/shell border injections combined) show that this latency is very short and narrowly distributed in the 0 s ITI task, but is longer and more variable in longer ITI tasks. Graphs show the mean (±SEM) across animals of the frequency of the latency given by the abscissa (bin width = 1 cm). Because animals cannot move long distances in <1 s, this implies that animals moved directly from the receptacle to the lever in the 0 s ITI task, but not necessarily in the longer ITI tasks. A, Inset, Mean receptacle exit to lever press latency increases for longer ITIs. The differences between each value and each of the other three values are significant. B, The latency to enter the reward receptacle after a lever press was short and narrowly distributed in all ITI tasks, suggesting that animals rarely deviated from a direct path between the two even in long-ITI tasks. B, Inset, Mean lever press to receptacle entry latency is short and does not vary substantially among the tasks (although the difference between the 0 and 20 s ITI tasks is significant). C, Video analysis of the cued FR1 task with 10 s ITI shows that dopamine antagonist injection in the NAc core decreased the likelihood that animals were in the third of the chamber nearest the lever at cue onset, and increased the likelihood that the animals were in the third of the chamber farthest from the lever. D, The antagonists increased the latency to respond after cue onset by a similar log unit value (i.e., by a similar proportion) no matter the animal's location at cue onset.