Abstract

The differential allocation hypothesis predicts that females modify their investment in a breeding attempt according to its reproductive value. One prediction of this hypothesis is that females will increase reproductive investment when mated to high-quality males. In birds, it was shown that females can modulate pre-hatch reproductive investment by manipulating egg and clutch sizes and/or the concentrations of egg internal compounds according to paternal attractiveness. However, the differential allocation of immune factors has seldom been considered, particularly with an experimental approach. The carotenoid-based ornaments can function as reliable signals of quality, indicating better immunity or ability to resist parasites. Thus, numerous studies show that females use the expression of carotenoid-based colour when choosing mates; but the influence of this paternal coloration on maternal investment decisions has seldom been considered and has only been experimentally studied with artificial manipulation of male coloration. Here, we used dietary carotenoid provisioning to manipulate male mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) bill coloration, a sexually selected trait, and followed female investment. We show that an increase of male bill coloration positively influenced egg mass and albumen lysozyme concentration. By contrast, yolk carotenoid concentration was not affected by paternal ornamentation. Maternal decisions highlighted in this study may influence chick survival and compel males to maintain carotenoid-based coloration from the mate-choice period until egg-laying has been finished.

Keywords: maternal investment, yolk carotenoid concentration, egg mass, albumen lysozyme concentration, paternal ornamentation, carotenoid-based coloration

1. Introduction

Life-history theory predicts that individual females might modulate their investment in a particular breeding attempt according to its reproductive value because a trade-off may exist between current and future reproduction [1]. One trait that females may use to adjust current effort is the quality of its mate. One prediction of this ‘differential allocation’ hypothesis (DAH, [2,3]) is that females will increase reproductive investment when mated to high-quality males. In a classic study, Burley [4] showed that female zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) paired to males with increased attractiveness produced more sons, the more beneficial sex to produce. Such an adjustment prioritizes the fitness of offspring in a current, valuable reproductive bout, given that the prospects for future survival or optimal mate quality or environmental conditions are comparatively much less certain.

When differentially apportioning reproductive effort by mate quality, there are several putative aspects of breeding that could be adjusted. The most obvious distinction is between pre-hatch (or birth) and post-hatch investments—namely whether embryonic, clutch or brood discrimination occurs at the level of the gamete, the physiological investments prior to hatch or birth, or behavioural adjustments that parents can make for live young. In birds, it was shown that females can modulate pre-hatch reproductive investment by manipulating egg and clutch sizes or the concentration of egg internal compounds [5–8] according to paternal attractiveness (see [9] for a review). However, the differential allocation of immune factors in the eggs according to paternal quality has seldom been considered, particularly with an experimental approach [10,11].

The sexual signals displayed by mates are often recognized as the most salient cues used by females to make differential allocation decisions. These include body size, song parameters, as well as coloration. After melanins, carotenoids are the second most prevalent pigments in the avian integument and determine yellow to red colour of many bird signals [12]. In addition, carotenoid pigments are involved in different physiological processes such as antioxidant and immuno-enhancing activities [12–17]. Thus, growing evidence suggests that individuals face a trade-off concerning the allocation of carotenoid pigments between immune function and ornamentation, which ensures the honesty of carotenoid-based sexual signals [18–21]. In this context, numerous experimental studies have been published on the signalling function of carotenoid-based coloration during the mate choice period (review in the study of Hill [22]; [23,24]), but the potential role of this coloration in maternal investment decisions has seldom been considered [4,7]. Moreover, the role of sexual attractiveness has only been experimentally considered with the use of artificial methods like coloured rings or markers for manipulating male carotenoid-based coloration and signals [2,6,7]. Follow-up studies, where researchers manipulate male carotenoid-based coloration within the natural range of coloration, would constitute a more natural test of the DAH [25].

The aim of this study was to test whether captive female mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) adjust current reproductive investment according to the carotenoid coloration of its mate. Male mallards have a bright yellow bill that contains carotenoid pigments [26–28], and females prefer to mate with males displaying yellower bills [29,30]. We used dietary carotenoid supplementation to experimentally manipulate male carotenoid bill coloration and randomly allocated a supplemented or unsupplemented male to each female for the entire first clutch. For the second clutch, we applied the same procedure by randomly allocating a different male, supplemented or not, to each female. This balanced experimental design allowed us to control for any individual variation in maternal reproductive investment that was not owing to mate quality (sensu [6,31]). From collected eggs, we quantified yolk carotenoid concentration and albumen lysozyme concentration as response variables, since these two egg parameters have been shown to influence chick development and survival [10,11,32,33]. Lysozyme is a major component of maternal innate antibacterial immunity transferred to the eggs in birds [11,34]. This enzyme acts by digesting bacterial walls [35–40]. Yolk carotenoids are crucial for the development of the embryonic immune system, given their potential protective role against oxidative stress during the first stages of life [41,42]. In addition, we considered clutch and egg size as an index of maternal investment. In mallards, where there is no parental food provisioning after hatch, increasing egg size improves offspring survival by producing heavier progeny [8].

As female mallards are known to increase egg size according to paternal attractiveness (as determined by female preference during mate choice trials; [8]), we predicted that females would lay bigger eggs when paired with supplemented males than with unsupplemented ones. In addition, based on the DAH, we predicted that females paired to more coloured males would deposit more carotenoids and lysozyme in their eggs.

2. Methods

Experiments were carried out at the Centre d'Etudes Biologiques de Chizé (CEBC) in Western France, using 40 adult duck pairs descended from individuals caught in the wild in three different areas. Birds were kept in semi-captive conditions (grassland of 800 m2) for at least 3 years before the experiments, and were therefore accustomed to their aviary environment. Individuals were fed with an ad libitum diet of water and a mixture of crushed corn, wheat and commercial duck food. Experiments were carried out in accordance with French veterinary services.

(a). Carotenoid provisioning

During the mate-choice period (i.e. three months before breeding, January), 40 males were randomly assigned to one of the two treatment groups: carotenoid-supplemented (n = 20) or controls (n = 20). Supplemented birds received 2 ml of a carotenoid mixture (Oro Glo liquid, 11 mg ml−1 lutein and zeaxanthin; Kemin France SRL, Nantes) every 3 days during two weeks (six treatments) using a plastic syringe that we inserted into their mouth. Unsupplemented birds received the same quantity of water with the same method. In a pilot study, we found that the quantity of carotenoids received by the treated group is the minimum required to observe a significant change in bill coloration one week after the end of the feeding period by spectrophotometry (M. Giraudeau, C. Duval, V. Bretagnolle & P. Heeb 2008, unpublished data). This carotenoid mixture was chosen because carotenoids present in the bill consist of lutein (the largest fraction) and approximately equal fractions zeaxanthin and 3-dehydrolutein [28].

Birds were captured the day before the beginning, 4 days after the end, and 10 weeks after the end of the supplementation for weighing and blood sampling. We drew 500 µl of whole blood from each bird through the alar vein with a heparinized syringe and immediately placed the sample on ice until centrifugation (10 000g for 3 min). Plasma was then frozen at −80°C for later analysis.

(b). Bill colour scoring and analyses

We scored bill colour 1 day before the beginning of the carotenoid supplementation and 10 weeks after the end of this treatment (before the breeding experiment). Bill colour was measured between 300 and 700 nm using an S-2000 spectrophotometer with a DH-2000-FHS deuterium-halogen light source (Ocean Optics, Eerbek, The Netherlands). Inclusion of the ultraviolet (UV; 320–400 nm) is necessary since ducks are sensitive to UV light [43]. The probe was held at a 90° angle to the bill and reflectance was measured on three different standardized spots under the nostril. Reflectance was calculated relative to a white standard and the three spectra obtained for each bird were averaged and summarized over 1 nm steps. From these spectrum measurements, we extracted hue, chroma, UV-chroma and brightness as response variables to assess variation in true coloration (see Loyau et al. [44] for a full description of these colour variables). Computations were conducted with the Avicol software [45].

(c). Effects of bill colour on egg investment

To examine the effects of male carotenoid provisioning on maternal investment, we used the same experimental design as Cunningham & Russell [8]. Briefly, females were housed individually in a pen of 6 m2 for about two weeks. Then, females were assigned one male for their first clutch; 20 females received a carotenoid-supplemented male and 20 an unsupplemented one. Pairs were housed together in holding pens until females had finished laying their entire clutch. Eggs were collected each day and replaced with a dummy egg to induce females to lay a normal clutch. All the eggs of the clutch were weighed. The first egg of each clutch was split open in a sterile Petri dish. Then, yolk and albumen were separated in two different Petri dishes and each of them was thoroughly mixed. Finally, we sampled 2 ml of albumen and yolk and immediately froze (−80°C) them until the determination of yolk carotenoid concentration and albumen lysozyme concentration.

After females had completed laying and males were removed, females then stayed alone for at least 17 days, the longest period a female mallard has been recorded to store sperm [46], so that all offspring in the second clutch were expected to be fathered only by the second male. For the second clutch, we randomly assigned another supplemented and unsupplemented male to each female and the same procedure was followed during egg-laying and collection. Thus, 10 females were subjected to each of the four possible combinations of mates (i.e. supplemented then supplemented, control then control, supplemented then control or control then supplemented).

(d). Assessment of egg compounds

To measure albumen lysozyme concentration, we used the lysoplate assay method of Osserman & Lawlor [47]: 25 µl of albumen was inoculated in the test holes of a 1 per cent agar gel (A5431, Sigma) containing 50 mg per 100 ml lyophilized Micrococcus lysodeikticus (M3770, Sigma) bacteria, which is particularly sensitive to lysozyme concentration. Crystalline hen egg white lysozyme (L6876, Sigma) was used to prepare a standard curve in each plate. Plates were incubated at room temperature (25–27°C) for 18 h; during this period, a zone of clearing developed in the area of the gel surrounding the sample inoculation site as a result of bacterial lysis. The diameters of the cleared zones are proportional to the log of the lysozyme concentration. This area was measured by using digital callipers and converted on a semi-logarithmic plot into hen egg lysozyme equivalents (expressed in microgrammes per millilitre) according to the standard curve [48].

Methods for plasma and yolk-carotenoid extractions and high-performance liquid chromatography analyses follow those described in McGraw et al. [49].

(e). Statistical procedures

As we weighed all eggs in each clutch, we used mean egg mass per clutch for the analyses using egg mass. We log-transformed yolk carotenoid concentration and albumen lysozyme concentration data to normalize them. To analyse maternal investment parameters (mean egg mass per clutch, clutch size, yolk carotenoid concentration and albumen lysozyme concentration), we performed generalized linear models with treatment of the male allocated to the females (supplemented or not), clutch order (clutch 1 or 2) and the interaction clutch order × male treatment as a fixed factor, female was included as a random factor. Finally, to test if egg parameters covaried, we have tested correlations between egg mass, albumen lysozyme and yolk carotenoid. Data were analysed using Statistica 6.0 software (Statsoft, Tulsa, OK, USA).

3. Results

(a). Plasma carotenoid concentration and bill coloration

Before carotenoid provisioning, supplemented and unsupplemented birds did not differ in mass (d.f. = 38, t = 0.76, p = 0.45) or tarsus length (d.f. = 38, t = 0.34, p = 0.74). Repeated-measures analysis of variance revealed no effect of carotenoid provisioning on body mass (F1,38 = 0.9, p = 0.35).

Plasma carotenoid concentrations were not significantly different between supplemented and unsupplemented males at the start of the experiment (d.f. = 38, t = 0.37, p = 0.71). Repeated-measures revealed that the amounts of circulating plasma carotenoids were not significantly affected by the supplementation (treatment × change in carotenoids interaction: F1,36 = 1.01, p = 0.33). This absence of difference of plasma carotenoids concentration between our two groups of birds only 4 days after the end of the treatment suggests that we did not give pharmacological dosage of carotenoid during supplementation.

Ten weeks after the end of the supplementation, before the maternal investment experiment, no significant difference of plasma carotenoids was detected between the two groups of males (d.f. = 38, t = −1.37, p = 0.18).

Before the carotenoid supplementation, males of the two groups did not differ significantly in the four variables of coloration measured (all tests p > 0.1; table 1). Carotenoid supplementation had the expected effect of creating two groups of male mallards that differed significantly in their bill coloration before the maternal investment experiment. Supplemented birds had significantly lower scores of bill brightness and UV-chroma and significantly higher scores of chroma and hue than unsupplemented birds (table 1).

Table 1.

Differences in mallard bill coloration between carotenoid-supplemented (CS) and unsupplemented (U) males before the supplementation and 10 weeks later (before breeding, d.f. = 38).

| t | mean (s.e.)CS/U | n | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| start of the experiment | ||||

| brightness | −1.04 | 5111(411)/5772(488) | 20/20 | 0.3 |

| hue | 1.58 | 531(1.9)/528(1.9) | 20/20 | 0.12 |

| chroma | 1.52 | 2.43(0.08)/2.29(0.05) | 20/20 | 0.14 |

| UV-chroma | −1.16 | 0.07(0.01)/0.08(0.01) | 20/20 | 0.25 |

| before breeding | ||||

| brightness | −2.54 | 4662(240)/5706(331) | 20/20 | 0.01 |

| hue | 1.96 | 530(1.8)/516(10) | 20/20 | 0.05 |

| chroma | 3.23 | 2.4(0.07)/2.07(0.07) | 20/20 | 0.002 |

| UV-chroma | −2.52 | 0.09(0.01)/0.15(0.02) | 20/20 | 0.02 |

Thus, supplementation did not result in increased blood carotenoid levels only 4 days after supplementation and yet resulted in increased bill coloration when measured 10 weeks later. Two mechanisms could explain these results. First, absorbed carotenoids were transferred to storage organs and later released in bill tissue. Second, only 4 days after the end of the carotenoid provisioning, absorbed carotenoids were taken up directly and completely by binding proteins in bill tissue.

(b). Maternal investment

(i). Egg mass and clutch size

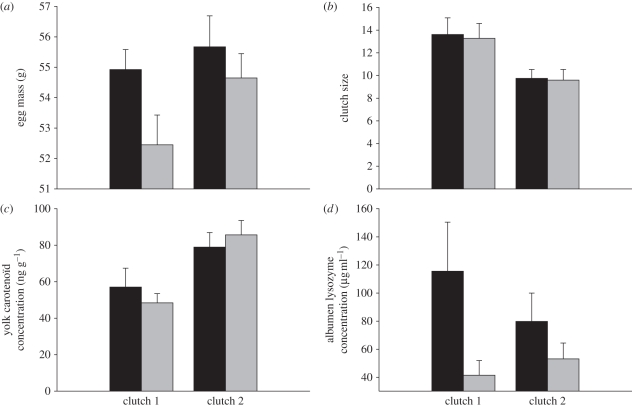

During the experiment, females paired to supplemented males produced heavier eggs than females paired to unsupplemented ones (figure 1a). Moreover, the mass of eggs laid tended to increase in the second clutch. The interaction between male treatment and clutch order did not affect egg mass (table 2).

Figure 1.

Maternal investment according to male treatment (carotenoid-supplemented (black bars) and unsupplemented males (grey bars)) during the two clutches (mean ± s.e.). (a) Egg mass, (b) clutch size, (c) yolk carotenoid concentration, and (d) albumen lysozyme activity.

Table 2.

Effect of carotenoid provisioning on maternal investment in eggs in captive breeding mallards.

| maternal investment variable | F1,75 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| clutch size | male treatment | 0.03 | 0.69 |

| clutch order | 8.6 | <0.001 | |

| male treatment × clutch order | 0.06 | 0.73 | |

| mean egg mass | male treatment | 3.90 | 0.05 |

| clutch order | 2.74 | 0.1 | |

| male treatment ×clutch order | 0.68 | 0.41 | |

| albumen lysozyme | male treatment | 3.97 | 0.02 |

| clutch order | 0.1 | 0.98 | |

| male treatment × clutch order | 0.76 | 0.43 | |

| yolk carotenoid | male treatment | 0.0001 | 0.87 |

| clutch order | 15.98 | <10−4 | |

| male treatment × clutch order | 1.04 | 0.52 |

The number of eggs per clutch decreased significantly from the first (13.46 eggs per clutch) to the second clutch (9.70 eggs per clutch), but no significant effect of male treatment and male treatment × clutch order interaction was found on clutch size (figure 1b and table 2).

(ii). Yolk carotenoids

We found that the concentration of carotenoids in the first egg increased with clutch order. However, the deposition of carotenoids in the yolk was not influenced by male treatment (figure 1c). The interaction between clutch order and male treatment did not significantly influence yolk carotenoid concentration (table 2).

(iii). Albumen lysozyme

Eggs laid by females paired to supplemented males during the experiment showed a higher lysozyme concentration than eggs laid by females paired to unsupplemented males (table 2). Clutch order and the male treatment × clutch order interaction did not influence albumen lysozyme concentration (figure 1d).

We found a significant effect of female identity on albumen lysozyme concentration (F1,75 = 2.1, p < 0.05) and egg mass (F1,75 = 3.9, p < 0.05) but not on clutch size (F1,75 = 0.5, p = 0.9) and yolk carotenoid concentration (F1,75 = 1.18, p = 0.3). Finally, we did not find any significant correlation between mean egg mass, carotenoid concentration and lysozyme concentration (p > 0.15).

4. Discussion

As predicted by the DAH, our study demonstrates that female mallards modulate egg mass and lysozyme deposition according to experimental manipulations of male carotenoid-based ornamentation. In birds, and particularly mallards, egg size positively influences chick mass and survival during the few days immediately after hatching, since it reflects the overall availability of reserves for the embryos [8,50]. Moreover, albumen lysozyme is involved in the egg's chemical defence, but also in physical defence by forming a fibrous network with other proteins [38]. Thus, a high level of lysozyme in the albumen increases embryo antibacterial defence during development [10,11]. By adjusting these two egg parameters simultaneously, females may influence offspring survival, growth and phenotype [51–54].

Recently, D'Alba et al. [55] provided the first correlative investigation of differential maternal investment in egg antimicrobial defence in relation to male attractiveness. Female blue tits (Cyanistes caeruleus) increased the amount of lysozyme they transferred to their eggs when mated to a more attractive male (higher UV-chroma). Here, our results constitute, to our knowledge, the first experimental demonstration of a differential allocation of lysozyme into albumen according to paternal coloration. Shawkey et al. [56] proposed recently that a trade-off between egg and blood immunity may not exist concerning this enzyme for two reasons: (i) egg and adult lysozyme are produced by different, specialized cells [57–59], and (ii) production and deposition of antimicrobials may be less costly than deposition of other yolk factors, such as carotenoids, antibodies and hormones (calculations from Tristam [60]). However, our data show that the deposition of this antibiotic in albumen is probably beneficial enough in some aspect(s) that females differentially allocate it according to the perceived value of one's mate and the associated reproductive bout. More studies are now needed to determine the immune and energetic costs and benefits of depositing varying amounts of lysozyme into eggs.

Contrary to our predictions, we did not find any effect of paternal coloration on yolk carotenoid concentration. At least two hypotheses could explain these results. First, paternal carotenoid-based coloration may not influence female allocation of carotenoid into eggs in mallards. Futures studies should examine the importance of other male mallard characteristics like plumage coloration on the differential allocation of carotenoids into eggs in this species. Second, several recent studies on passerine birds showed that results differ depending on whether yolk carotenoid concentration or quantity is considered [61,62]. Safran et al. [61] proposed that a higher concentration may increase the dose of a compound during a given interval of embryonic development, whereas a greater amount may mean prolonged exposure during development. Thus, further studies should examine how the total amount of yolk carotenoid varies according to the experimental manipulation of male bill coloration in mallards. We unfortunately did not weigh fresh whole yolks in this study, so we cannot comment on total carotenoid quantity in egg yolks of mallards here.

Our results raise the question of the functional significance of this differential maternal investment driven by the degree of male ornamentation in a species where males do not provide any parental care [8]. First, male mallards may use carotenoid-based coloration to signal their dominance status and thereby the feeding areas available to females and their offspring during the breeding season [8]. It has been suggested in several bird species that carotenoid-based coloration is associated with intense male–male competition for territories [63–67]. However, to our knowledge, this potential role of male mallard bill coloration has not yet been studied.

Second, only males of high genetic quality or males in good phenotypic condition may be able to develop and maintain intense carotenoid-based displays [68,69] and transmit genes for parasitic resistance and attractiveness to offspring [70]. For example, in mallards, male bill colour signals immunocompetence [28]. Thus, females could use carotenoid-based signals to evaluate male genetic quality and may invest more in those advertising good genes for immune status or antioxidant system efficiency [44,71,72]. Third, it was demonstrated in mallards that male bill coloration, and particularly relative UV reflectance, is negatively correlated with sperm velocity [28]. Thus, by modulating egg mass and lysozyme deposition according to male bill UV reflectance, females may increase their investment in a particular breeding attempt with a more fertile male.

During our experiment, clutch order strongly influenced yolk carotenoid concentration and clutch size and tended to influence egg mass, indicating that female mallards laid fewer eggs in the second clutch but produced heavier eggs that contained higher yolk carotenoid concentrations. These results are in accordance with previous studies in passerines, which found that clutch size declines [73,74] and egg size increases [75] with the advance of the breeding season. An explanation is that females may produce heavier chicks with more reserves late in the season to compensate the low availability of food at this period [76].

In conclusion, our findings contribute to the limited information on the deposition of immune compounds in eggs according to paternal attractiveness. Thus, this study provides, to our knowledge, the first experimental demonstration of a differential allocation of lysozyme into eggs. Deposition of lysozyme and egg masses depended on the expression of a paternal secondary sexual character and this may reflect adaptive maternal strategies. In addition, we provide, to our knowledge, the first experimental demonstration of the importance of carotenoid-based paternal ornamentation on maternal investment, where signals were manipulated directly by carotenoid provisioning. Thus, mothers may alter their investment in egg production in response to male carotenoid-based ornamentation, since attractive males are more likely to sire successful offspring with attractiveness and parasite-resistance genes.

Acknowledgements

Housing conditions and the experiment were carried out in compliance with European legal recruitment and national permissions (ETS123).

We are grateful to Marco Cucco for his help in lysozyme analyses. We thank Colette Trouvé, Stephanie Dano, André Lacroix and Noël Guillon for their help in the fieldwork and preparation of the samples, and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments. This project was supported by a French research grant (ANR-05, NT05-3_42075) to P.H. During this study, G.Á.C. was supported by a PhD scholarship of the Romanian Ministry of Education and Research and by an Eiffel grant from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. K.J.M. was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant no. IOS-0746364).

References

- 1.Stearns S. C. 1992. The evolution of life histories. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burley N. 1986. Sexual selection for aesthetic traits in species with biparental care. Am. Nat. 127, 415–445 10.1086/284493 (doi:10.1086/284493) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burley N. 1988. The differential allocation hypothesis: an experimental test. Am. Nat. 132, 611–628 10.1086/284877 (doi:10.1086/284877) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burley N. 1981. Mate choice by multiple criteria in a monogamous species. Am. Nat. 117, 515–528 10.1086/283732 (doi:10.1086/283732) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petrie M., Williams A. 1993. Peahens lay more eggs for peacocks with larger trains. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 251, 127–131 10.1098/rspb.1993.0018 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1993.0018) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gil D., Graves J., Hazon N., Wells A. 1999. Male attractiveness and differential testosterone investment in zebra finch eggs. Science 286, 126–128 10.1126/science.286.5437.126 (doi:10.1126/science.286.5437.126) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velando A., Beamonte-Barrientos R., Torres R. 2006. Pigment-based skin colour in the blue-footed booby: an honest signal of current condition used by females to adjust reproductive investment. Oecologia 149, 535–542 10.1007/s00442-006-0457-5 (doi:10.1007/s00442-006-0457-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham E. J. A., Russell A. F. 2000. Egg investment is influenced by male attractiveness in the mallard. Nature 404, 74–76 10.1038/35003565 (doi:10.1038/35003565) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheldon B. C. 2000. Differential allocation: tests, mechanisms and implications. Trends Ecol. Evol. 15, 397–402 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01953-4 (doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01953-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saino N., Bertacche V., Ferrari R. P., Martinelli R., Møller A. P., Stradi R. 2002. Carotenoid concentration in barn swallow eggs is influenced by laying order, maternal infection and paternal ornamentation. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 266, 1729–1733 10.1098/rspb.2002.2088 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2088) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saino N., Ferrari R. P., Martinelli M. R., Rubolini D., Møller A. P. 2002. Early maternal effects mediated by immunity depend on sexual ornamentation of the male partner. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 1005–1009 10.1098/rspb.2002.1992 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.1992) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGraw K. J. 2006. The mechanics of carotenoid coloration in birds. In Bird coloration. I. Mechanisms and measurements (eds Hill G. E., McGraw K. J.), pp. 177–242 Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burton G. W. 1989. Antioxidant action of carotenoids. J. Nutr. 119, 109–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krinsky N. I. 1989. Antioxidant functions of carotenoids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 7, 617–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blount J. D., McGraw K. J. 2008. Control and function of carotenoid coloration in birds: a review of case studies. In Carotenoids: physical, chemical, and biological functions and properties (ed. Landrum J. T.), pp. 213–236 Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Agamey A., Lowe G. M., McGarvey D. J., Mortensen A., Phillip D. M., George Truscott T., Young A. J. 2004. Carotenoid radical chemistry and antioxidant/pro-oxidant properties. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 430, 37–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bendich A. 1993. Biological functions of dietary carotenoids. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 691, 61–67 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26157.x (doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26157.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lozano G. A. 1994. Carotenoids, parasites, and sexual selection. Oikos 70, 309–311 10.2307/3545643 (doi:10.2307/3545643) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Von Schantz T., Bensch S., Grahn M., Hasselquist D., Wittzell H. 1999. Good genes, oxidative stress and condition-dependent sexual signals. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 266, 1–12 10.1098/rspb.1999.0597 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0597) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faivre B., Gregoire A., Preault M., Cezilly F., Sorci G. 2003. Immune activation rapidly mirrored in a secondary sexual trait. Science 300, 29–31 10.1126/science.1081802 (doi:10.1126/science.1081802) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGraw K. J., Ardia D. R. 2003. Carotenoids, immunocompetence, and the information content of sexual colours: an experimental test. Am. Nat. 162, 704–712 10.1086/378904 (doi:10.1086/378904) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill G. E. 1999. Mate choice, male quality, and carotenoid-based plumage coloration. In Proc. 22nd Int. Ornithological Congress, Johannesburg, 1999 (eds Adams N., Slotow R.), pp. 1654–1668 Durban: University of Natal [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill G. E. 2002. A red bird in a brown bag: the function and evolution of ornamental plumage coloration in the house finch. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 24.Møller A. P., Biard C., Blount J. D., Houston D. C., Ninni P., Saino N., Surai P. F. 2000. Carotenoid dependent signals: indicators of foraging efficiency, immunocompetence, or detoxification ability? Avian Poultry Biol. Rev. 11, 137–159 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill G. E. 2006. Female mate choice for ornamental coloration. In Bird coloration. Vol. 2: function and evolution (eds Hill G. E., McGraw K. J.), pp. 137–200 Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lonnberg E. 1938. The occurrence and importance of carotenoid substances in birds. Int. Orn. Congr. 8, 410–424 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cramp S., Simmons K. E. L. 1977. Birds of the Western Palearctic, vol. 1, pp. 505–519 London, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters A., Denk A. G., Delhey K., Kempenaers B. 2004. Carotenoid-based bill colour as an indicator of immunocompetence and sperm performance in male mallards. J. Evol. Biol. 17, 1111–1120 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00743.x (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00743.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Omland K. E. 1996. Female mallard mating preferences for multiple male ornaments. I. Natural variation. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 39, 353–360 10.1007/s002650050300 (doi:10.1007/s002650050300) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omland K. E. 1996. Female mallard mating preferences for multiple male ornaments. II. Experimental variation. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 39, 361–366 10.1007/s002650050301 (doi:10.1007/s002650050301) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGraw K. J., Adkins-Regan E., Parker R. S. 2005. Maternally derived carotenoid pigments affect offspring survival, sex ratio, and sexual attractiveness in a colourful songbird. Naturwissenschaften 92, 375–380 10.1007/s00114-005-0003-z (doi:10.1007/s00114-005-0003-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romano M., Caprioli M., Ambrosini R., Rubolini D., Fasola M., Saino N. 2008. Maternal allocation strategies and differential effects of yolk carotenoids on the phenotype and viability of yellow-legged gull (Larus michahellis) chicks in relation to sex and laying order. J. Evol. Biol. 21, 1826–1840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biard C., Surai P. F., Møller A. P. 2005. Effects of carotenoid availability during laying on reproduction in the blue tit. Oecologia 144, 32–44 10.1007/s00442-005-0048-x (doi:10.1007/s00442-005-0048-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saino N., Dall'ara P., Martinelli R., Moller A. P. 2002. Early maternal effects and antibacterial immune factors in the eggs, nestlings and adults of the barn swallow. J. Evol. Biol. 15, 735–743 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00448.x (doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00448.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato Y., Watanabe K. 1976. Lysozyme in hen blood serum. Poultry Sci. 55, 1749–1756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clark A. G., Bueschkens D. H. 1986. Survival and growth of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Food Prot. 49, 135–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grinde B. 1989. Lysozyme from rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri as an antibacterial agent against fish pathogens. J. Fish Dis. 12, 95–104 10.1111/j.1365-2761.1989.tb00281.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2761.1989.tb00281.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trziszka T. 1994. Lysozyme and its functions in the egg. Arch. Geflugelk 58, 49–54 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braun P., Fehlhaber K. 1996. Studies of the inhibitory effect of egg albumen on gram-positive bacteria and on Salmonella enteritidis strains. Arch. Geflugel 60, 203–207 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kudo S. 2000. Enzymes responsible for the bactericidal effect in extracts of vitelline and fertilisation envelopes of rainbow trout eggs. Zygote 8, 257–265 10.1017/S0967199400001052 (doi:10.1017/S0967199400001052) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pastoret P., Gabriel P., Bazin H., Govaerts A. 1998. Handbook of vertebrate immunology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saino N., Ferrari R. P., Martinelli S. R., Romano M., Rubolini D., Moller S. 2003. Early maternal effects mediated by immunity depend on sexual ornamentation of the male partner. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 1005–1009 10.1098/rspb.2002.1992 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.1992) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parrish J., Benjamin R., Smith R. 1981. Near-ultraviolet light reception in the mallard. Auk 98, 627–628 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loyau A., Gomez D., Moureau B., Thery M., Hart N. S., Saint Jalme M., Bennett A. T. D., Sorcie G. 2007. Iridescent structurally based coloration of eyespots correlates with mating success in the peacock. Behav. Ecol. 18, 1123–1134 10.1093/beheco/arm088 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arm088) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gomez D. 2007. Avicol v. 2, a program to analyse spectrometric data. Available upon request from the author at dodogomez@yahoo.fr

- 46.Elder W. H., Weller M. W. 1954. Duration of fertility in the domestic mallard hen after isolation from the drake. J. Wildl. Manage. 18, 495–502 10.2307/3797084 (doi:10.2307/3797084) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osserman E. F., Lawlor D. P. 1966. Serum and urinary lysozyme (muraminidase) in monocytic and monomyelocytic leukaemia. J. Exp. Med. 124, 921–951 10.1084/jem.124.5.921 (doi:10.1084/jem.124.5.921) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cucco M., Guasco B., Malacarne G., Ottonelli R. 2007. Effects of β-carotene on adult immune condition and antibacterial concentration in the eggs of the grey partridge, Perdix perdix. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 147, 1038–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGraw K. J., Gregory A. J., Parker R. S., Adkins-Regan E. 2003. Diet, plasma carotinoids and sexual coloration in the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata). Auk 120, 400–410 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rhymer J. M. 1988. The effect of egg size variability on thermoregulation of mallard Anas platyrhynchos offspring and its implications for survival. Oecologia 75, 20–24 10.1007/BF00378809 (doi:10.1007/BF00378809) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaplan R. H. 1985. Maternal influences on offspring development in the California newt, Taricha torosa. Copeia 85, 1028–1035 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mousseau T. A., Fox C. W. 1998. Maternal effects as adaptations. New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 53.Price T. 1998. Maternal and paternal effects in birds: effects on offspring fitness. In Maternal effects as adaptations (eds Mousseau T. A., Fox C. H.), pp. 202–226 Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wade M. J. 1998. The evolutionary genetics of maternal effects. In Maternal effects as adaptations (eds Mousseau T. A., Fox C. H.), pp. 5–21 Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 55.D'Alba L., Shawkey M., Korsten P., Vedder O., Kingma S. A., Komdeur J., Beissinger S. R. 2010. Differential deposition of antimicrobials proteins in blue tit (Cyanistes caeruleus) clutches by laying order and male attractiveness. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 64, 1037–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shawkey M. D., Kosciuch K. L., Liu M., Rohwer F. C., Loos E. R., Wang J. M., Beissinger S. R. 2008. Do birds differentially distribute antimicrobial proteins within clutches of eggs? Behav. Ecol. 19, 920–927 10.1093/beheco/arn019 (doi:10.1093/beheco/arn019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mandeles S., Ducay E. D. 1962. Site of egg white protein formation. J. Biol. Chem. 237, 3196–3199 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shutz G., Nguyen-Huu M. C., Giesecke K., Hynes N. E., Groner B., Wurtz T., Sippel A. E. 1978. Hormonal control of egg-white protein messenger RNA synthesis in the chicken oviduct. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 42, 617–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moen R. C., Palmiter R. D. 1980. Changes in hormone responsiveness of chicken oviduct during primary stimulation with estrogen. Dev. Biol. 78, 450–463 10.1016/0012-1606(80)90346-2 (doi:10.1016/0012-1606(80)90346-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tristam G. R. 1953. Amino acid composition of the proteins. In The proteins (eds Neuarth H., Bailly K.), pp. 181–233 New York, NY: Academic Press Inc [Google Scholar]

- 61.Safran R. J., Pilz K. M., McGraw K. J., Correa S. M., Schwabl H. 2008. Are yolk androgens and carotenoids in barn swallow eggs related to parental quality? Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 62, 427–438 10.1007/s00265-007-0470-7 (doi:10.1007/s00265-007-0470-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pilz K. M., Smith H. G., Sandell M., Schwabl H. 2003. Inter-female variation in egg yolk androgen allocation in the European starling: do high quality females invest more? Anim. Behav. 65, 841–850 10.1006/anbe.2003.2094 (doi:10.1006/anbe.2003.2094) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roskaft E., Rohwer S. 1987. An experimental study of the function of the red epaulettes and black body colour of male red-winged blackbirds. Anim. Behav. 35, 1070–1077 10.1016/S0003-3472(87)80164-1 (doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(87)80164-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Evans M. R., Hatchwell B. J. 1992. An experimental study of male adornment in the scarlet-tufted Malachite sunbird: II. The role of the elongated tail in mate choice and experimental evidence for a handicap. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 29, 421–427 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pryke S. R., Anderson S., Lawes M. J., Piper S. E. 2002. Carotenoid status signalling in captive and wild red-collared widowbirds: independent effects of badge size and colour. Behav. Ecol. 13, 622–631 10.1093/beheco/13.5.622 (doi:10.1093/beheco/13.5.622) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pryke S. R., Anderson S. 2003. Carotenoids-based epaulettes reveal male competitive ability; experiments with resident and floater red-shouldered window-birds. Anim. Behav. 66, 217–224 10.1006/anbe.2003.2193 (doi:10.1006/anbe.2003.2193) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pryke S. R., Anderson S. 2003. Carotenoid-based status signalling in red-shouldered widow-birds (Euplectes axillaris): epaulet size and redness affect captive and territorial competition. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 53, 393–401 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trivers R. L. 1972. Parental investment and sexual selection. In Sexual selection and the descent of man (ed. Campbell B.), pp. 136–179 Chicago, IL: Aldine [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zahavi A. 1975. Mate selection: a selection for a handicap. J. Theor. Biol. 53, 205–214 10.1016/0022-5193(75)90111-3 (doi:10.1016/0022-5193(75)90111-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hamilton W. D., Zuk M. 1982. Heritable true fitness and bright birds: a role for parasites. Science 218, 384–387 10.1126/science.7123238 (doi:10.1126/science.7123238) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bendich A. 1989. Carotenoids and the immune response. J. Nutr. 119, 112–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blount J. D., Metcalfe N. B., Birkhead T. R., Surai P. F. 2003. Carotenoid modulation of immune function and sexual attractiveness in zebra finches. Science 300, 125–127 10.1126/science.1082142 (doi:10.1126/science.1082142) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Klomp H. 1970. The determination of clutch size in birds. A review. Ardea 58, 1–124 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nilsson J. A. 1991. Clutch size determination in the marsh tit (Parus palustris). Ecology 72, 1757–1762 10.2307/1940974 (doi:10.2307/1940974) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Verhulst S., Van Balen J. H., Tinbergen J. N. 1995. Seasonal decline in reproductive success of the great tit: variation in time or quality? Ecology 76, 2392–2403 10.2307/2265815 (doi:10.2307/2265815) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nilsson J. Å. 2000. Time-dependent reproductive decisions in the blue tit. Oikos 88, 351–361 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.880214.x (doi:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.880214.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]