Abstract

Modular tissue engineering is a novel approach to creating scalable, self-assembling, three-dimensional tissue constructs with inherent vascularisation. Under initial methods, the subcutaneous implantation of human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC)-covered collagen modules in immunocompromised mice resulted in significant host inflammation and limited HUVEC survival. A minimally-invasive injection technique was used to minimize surgery-related inflammation, and cell death was attributed to extensive apoptosis within 72 hours of implantation. Coating collagen modules with fibronectin (Fn) was shown in vivo to reduce short-term HUVEC TUNEL staining by nearly 40%, while increasing long-term HUVEC survival by 30% to 45%, relative to collagen modules without fibronectin. Consequently, a 100% increase in the number of HUVEC-lined vessels was observed with Fn-coated modules, as compared to collagen-only modules, at 7 and 14 days post-implantation. Furthermore, vessels appeared to be perfused with host erythrocytes by day 7, and vessel maturation and stabilization was evident by day 14.

Introduction

Without an internal vasculature, the viability of cells in tissue constructs must initially depend solely on diffusion [1]. In fact, angiogenic control has been identified as the strategically most important factor for the clinical success of the tissue engineering field [2]. Tissue growth beyond the diffusion limit of oxygen (100 – 200 μm) requires new vessel formation [3]. Several strategies for improved vascularisation are imperative for the success of large tissue-engineered grafts: (1) the use of angiogenic factors to induce surrounding vessels to infiltrate the tissue upon implantation; (2) the use of a scaffold seeded with endothelial cells (EC) to improve the rate of vascularisation; and (3) the prevascularisation of a matrix prior to implantation [4,5].

We are exploring a potentially scalable, self-assembling vascularised 3-dimensional tissue construct known as modular tissue engineering [6]. Cells are embedded in short, sub mm-sized, cylindrical ‘modules’ with the outer surface covered in a confluent layer of EC. The random assembly of modules, typically made with collagen gel, into a larger ‘modular construct’ results in EC-lined interstitial spaces, presenting a non-thrombogenic surface and enabling blood perfusion throughout the interconnected channels. Although not capillary-like in scale or structure, the seeded ECs have been shown to prevent thrombosis through the expression/secretion of various control molecules [7]. Various cell types (such as liver, heart, and pancreatic islet cells) may be embedded within the modules. An initial in vivo study involving the transplantation of human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC)-covered modules (containing no embedded cells) into the omental pouch of nude rats (treated with clodronate liposomes to deplete peritoneal macrophages) demonstrated the random assembly of modules to form HUVEC-lined channels [8]. Encouragingly, HUVEC-derived vessels were observed by day 3 and persisted to day 7, however host inflammation limited HUVEC survival beyond 3 days. These results suggest that a decreased host response and improved HUVEC survival may allow cells embedded in modules to be adequately perfused.

Cultured EC have been shown to rapidly undergo apoptosis upon in vivo implantation [4]. Divided into distinct biochemical and morphological phases, apoptosis is irreversibly triggered several hours before the appearance of hallmark morphological features in the late stages of the 6 – 24 h apoptotic cell death process [9]. Apoptotic HUVEC are also strongly procoagulant and rapidly bind non-activated platelets [10], suggesting that the prevention of apoptosis is necessary not only from the standpoint of cell survival, but also in regards to allowing blood perfusion throughout the implant site. The extent of apoptosis appears to be dependent on the culture substrate: collagen, fibronectin (Fn), laminin, and vitronectin all suppress HUVEC apoptosis to some extent [11], with fibronectin shown to be the most effective. Specifically, it was found that the suppression of HUVEC apoptosis is, at least in part, due to ligation of the α5β1, αvβ3, and α2β1 integrins by fibronectin, vitronectin, and collagen, respectively. Not only has fibronectin been well documented as an important substance for cell adhesion, migration, signaling, proliferation, and survival [12], but its combination with the structural properties of type I collagen fibers has already shown promise for the formation of a HUVEC-based vasculature [13].

This study aimed to: (1) determine the in vivo response to the implantation of HUVEC-covered collagen modules (without embedded cells) in a severe combined immunodeficient/beige (SCID/Bg) mouse model, one that is more commonly used in the literature than the nude rat; (2) optimize the module implantation technique to minimize surgery-related inflammation; and (3) examine the effectiveness of coating the collagen modules with fibronectin with the goal of reducing apoptosis and improving HUVEC survival and blood vessel formation throughout the implanted construct.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Culture

Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC, Cambrex Bioscience, Walkersville, MD) were cultured in growth factor supplemented EGM-2 medium (Cambrex Bioscience) at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 95% air, and 100% humidity. EGM-2 medium was supplemented with the EBM-2 bullet kit growth supplement mixture from Cambrex. Cells were used between passages 3 to 6.

Module Fabrication and Cell Seeding

Acidified bovine type I collagen solution (3.1 mg/mL, PureCol, Inamed Biomaterials, CA) was mixed with 10X minimum essential medium (MEM) and neutralized with 0.8 M NaHCO3 to prepare modules as described elsewhere [6] using 0.76 mm ID polyethylene tubing (Intramedic PE60, Benton Dickson). Where modules were coated with fibronectin, they were placed in a 10 μg/mL Fn (from 0.1% fibronectin solution from bovine plasma, Sigma Aldrich) in dH2O solution on a low-speed uniaxial rocker overnight at 37 °C. For endothelial cell seeding, 2.0 × 106 HUVEC per 3 m tubing were dynamically seeded on a low-speed uniaxial rocker for 30 minutes at 37 °C. Modules were cultured with fresh HUVEC medium for at least 4 days prior to implantation.

Immunofluorescence Staining and Confocal Imaging

To assess HUVEC viability on collagen modules, a two colour Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (Molecular Probes, L3224) was used following the manufacturer’s procedures and visualized using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope. VE-cadherin staining was done as described elsewhere [14] using a polyclonal rabbit anti-human VE-cadherin antibody (Sigma Aldrich) and Alexa Fluor 488 secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes).

In vitro HUVEC Apoptosis/TUNEL staining

TCPS flasks were coated with either fibronectin (from 0.1% fibronectin solution from bovine plasma, Sigma Aldrich) or type I collagen (PureCol, Inamed Biomaterials, CA). Plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with 10 μg/mL of the indicated ECM component in dH2O. HUVEC were seeded onto these plates and cultured to confluence over 4 days. HUVEC were also seeded on either Fn-coated or collagen-only modules (prepared as described above) and cultured to confluence over 4 days.

Once confluent, growth factor supplemented EGM-2 medium was replaced with serum-free medium (EGM-2 medium supplemented with 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin only). Negative control cells continued to be cultured with growth factor supplemented EGM-2 medium. For cells on TCPS, after 5 days under serum-free conditions, both detached and adherent HUVEC were collected and approximately 1–2 × 106 cells were suspended in 0.5 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For modules, a serial digestion procedure was used to collect HUVEC adhered to the module surface after 7 days in serum-free culture. Approximately 1.5 × 103 HUVEC-covered modules were collected and suspended in 0.5 mL of 5 mg/ml Collagenase/Dispase (Roche) in HUVEC medium (filtered through a sterile 0.22 μm membrane filter). The modules were stirred slowly for 30 minutes at 37 °C and cells were decanted off every 10 minutes and added to 10 mL of ice-cold medium. After each decanting stage, the remaining modules were washed with 0.5 mL medium and resuspended in 0.5 mL of 5 mg/mL Collagenase/Dispase solution. The resulting cell suspension was washed with 5 mL PBS, then resuspended in 0.5 mL PBS.

The cell suspension, from modules or TCPS flasks, was fixed in 5 mL of 1% (w/v) paraformaldehyde solution (Electron Microscopy Science) on ice for 15 minutes. The cells were twice washed with 5 mL PBS, then resuspended in 0.5 mL PBS and added to 5 mL of ice-cold 70% (v/v) ethanol. Cells were stored at −20 °C for 24 h prior to performing the TUNEL assay.

An APO-BrdU TUNEL Assay Kit (Molecular Probes) was used to detect apoptotic cells. Fixed cells, along with provided positive and negative control cells (fixed human lymphoma cell line suspensions of 1–2 × 106 cells/mL in 70% ethanol), were washed with wash buffer (2 × 1 mL), then resuspended in 50 μL of the DNA-labeling solution (10 μL reaction buffer, 0.75 μL terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) enzyme, 8.0 μL BrdUTP, and 31.25 μL dH2O). Samples were incubated for 1.5 h at 37 °C and shaken every 15 minutes. Cells were washed with rinse buffer (2 × 1.0 mL) and resuspended in 100 μL of antibody staining solution (5.0 μL Alexa Fluor 488 dye-labeled anti-BrdU antibody and 95 μL rinse buffer). Samples were incubated for 30 minutes in the dark at room temperature. 0.5 mL of propidium iodide/RNase A staining buffer was added to each sample and the cells were incubated for an additional 30 minutes in the dark at room temperature. Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry within 3 h of completing the staining procedure. Flow cytometry was performed using Expo32 ADC (version 1.1C) software in combination with a Beckman Coulter Epics XL cytometer.

Module Implantation

Male (5–6 weeks of age) Fox Chase severe combined immunodeficient/beige (SCID/Bg) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. After surgery, mice were individually housed in sterile cages and provided free access to sterilized food and water. The study was approved by the University of Toronto Animal Care Committee.

Two methods were used for implantation. One method used a subcutaneous pocket created by blunt dissection. In the other method, modules were simply injected. Prior to implantation, mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation. The dorsal area was shaved and the exposed skin was cleansed with 70% (v/v) ethanol and Betadine. In the implantation method, using sterile technique, an incision 5 mm in length was made on the back of each mouse. A single subcutaneous pocket was created beneath the incision by blunt dissection. Into the pouch, approximately 200 modules in 0.5 mL PBS were gently delivered through a micropipette. The incision was then closed with sutures and animals were given Buprenorphine for recovery. Only modules not coated with fibronectin were implanted by this method.

For injection, approximately 200 modules in 0.2 mL PBS were injected subcutaneously at each of two separate sites lateral to one another on the back of the mouse through an 18G1” needle using a 1 mL syringe. At each experimental time point, animals were sacrificed and the implant, as well as surrounding tissue, was explanted for histology.

In one series of experiments, the response to modules, without fibronectin, was compared, qualitatively, using the two implantation methods (n = 3). In another series, HUVEC covered, fibronectin coated modules were injected on one side and HUVEC covered modules, without fibronectin were injected on the other side of the same animals (n = 5).

Histology

Explanted tissues were placed in 4% neutral buffered formalin and fixed for 48 hours. All processing and immunostaining procedures were carried out by the clinical research pathology lab at the Toronto General Hospital. Three level sections (50 μm apart, 4 μm thick) were cut, processed and stained for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson’s trichrome, anti-human EC lectin Ulex Europaeus Agglutinin I (UEA-1), smooth muscle α-actin (SMA), and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labelling (TUNEL). Trichrome stains collagen and was used to locate modules in each section, while UEA-1 identified HUVEC (did not stain host EC), and TUNEL marked late-phase apoptosis. All pictures were taken with a Zeiss Axiovert light microscope equipped with a CCD camera.

Histology Quantification

Cells positively stained for UEA-1 were counted using a Chalkley method previously adapted from tumor angiogenesis literature [8]. Within regions identified as the implanted modular construct, four hotspots were selected as areas containing the most positively stained cells in each section. At each hotspot, a 25-point Chalkley eyepiece graticule was applied (Chalkley grid area = 0.196 mm2) at 400x magnification. The eyepiece was then rotated to align the maximum number of dots with UEA-1 positive structures (either vessels or single cells). In each case, the dots that overlaid UEA-1 positive structures were counted and the mean of the highest three counts (i.e. the lowest number was dropped) was used for statistical analysis. The same procedure was used for counting cells positively stained for TUNEL in each section.

Subsequently, UEA-1 positive vessels (with a defined lumen) were counted using the microvessel density (MVD) method. For each implant site, the number of vessels in four hotspots was counted at 400x magnification. As before, the average of the highest three counts for each implant was used for statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

For in vitro studies evaluating HUVEC TUNEL staining, a one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc analysis was applied to compare means between multiple groups. To assess in vivo differences in HUVEC survival, TUNEL staining, and vessel formation between Fn-coated and collagen-only modular constructs, a paired-samples t-test was used. In all cases, data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. All analysis was performed with SPSS 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

In vitro HUVEC Characteristics and TUNEL staining

HUVEC survival and morphology was assessed over 42 days in culture (Figure 1). As expected, HUVEC demonstrated excellent survival over the time studied. Furthermore, VE-cadherin staining revealed the long-term maintenance of cell junctions suggesting that HUVEC are capable of remaining in a quiescent state when cultured on collagen modules for periods of at least 42 days.

Figure 1.

HUVEC-covered collagen modules were assessed in vitro for EC viability and cell-cell junction integrity over a six week period. Live/dead assay reveals excellent cell viability (green) with no visible dead cells (red). VE-cadherin staining shows fully stabilized junctions at all time points. Scale bar = 200 μm.

As a first step towards exploring a minimally invasive method of deploying HUVEC covered modules in vivo, HUVEC-covered modules were passed through needles ranging in size from 18 gauge to 23 gauge, all at roughly the same hand-generated operating pressure. The resultant modules were fixed and labeled with VE-cadherin to evaluate the remaining EC coverage. Although HUVEC confluence was severely disrupted when passed through the smaller needles, confluent EC coverage was maintained with the 18G needle (Figure 2) with almost all modules. From these results, the injection procedure involved a simple subcutaneous injection using an 18G1” needle with a 1 mL syringe.

Figure 2.

Confocal images of initially confluent HUVEC-covered modules after having been passed through needles of various sizes in vitro (A = control, prior to study; B = 23G needle; C = 20G; D = 18G). VE-cadherin staining shows EC disruption in each case, except for that of the 18G needle. As a result, an 18G1” needle was selected for subcutaneously injecting modules in the injection procedure. Scale bar = 100 μm

A pilot study indicated significant TUNEL staining at early times after implantation and so the modules were coated with fibronectin prior to seeding with HUVEC with a view to reducing this. To test the utility of this coating, TUNEL staining was induced in HUVEC in vitro: serum-free medium was used to starve the cells of essential survival factors. Through pilot studies, day 5 was chosen as a suitable time point for evaluating HUVEC survival on coated TCPS and day 7 was chosen similarly for HUVEC on modules and results are shown in Figure 3. As expected, fibronectin coating on TCPS suppressed HUVEC TUNEL staining significantly (p < 0.01) more than collagen under serum-free conditions (Figure 3A). Approximately 25% of HUVEC were TUNEL positive while seeded on collagen coated TCPS, as compared to only 12% on fibronectin coated TCPS, whereas negligible TUNEL staining (less than 0.5%) was observed in each negative control. These results compare well to a study that found about 12% of HUVEC underwent apoptosis in the presence of fibronectin versus 20% with collagen [11] and are further supported by work demonstrating a 60% increase in EC survival on fibronectin, as compared to collagen [16].

Figure 3.

Summary of TUNEL assay flow cytometry results comparing HUVEC under serum-free conditions when cultured on (A) Fn-coated vs. collagen-coated TCPS flasks for 5 days, and (B) Fn-coated vs. collagen-only modules for 7 days. Results from both experiments show fibronectin significantly reduced HUVEC TUNEL staining as compared to collagen. * indicates p < 0.05 (Tukey post-hoc); error bars represent mean ± SEM (n=3); COL = collagen-only modules; Fn = fibronectin-coated collagen modules; Ctrl = negative control/cultured in complete HUVEC medium; SF = cultured under serum-free conditions.

For HUVEC on modules, TUNEL staining was also significantly (p = 0.046) suppressed by fibronectin, as compared to collagen (Figure 3B). However, here the need to digest the modules to recover the HUVEC increased the overall level of TUNEL staining, presumably because of the multiple manipulations involved in recovering the cells. For modules, approximately 68% of HUVEC on collagen-only modules were TUNEL positive versus 38% on Fn-coated modules. It was also noted that roughly 20% of cells were TUNEL positive in each negative control – presumably as a result of the multiple manipulations associated with module digestion.

Module implantation

In an attempt to evaluate the in vivo behavior of HUVEC-covered collagen modules independent of a complete immune response, immunocompromised SCID/Bg mice were used and modules were implanted in surgically created subcutaneous pockets. The SCID/Bg mouse carries two genetic defects: (1) the murine SCID mutation which results in the absence of mature B- and T-lymphocytes; and (2) the beige mutation that causes defective natural killer (NK) cells. Due to the resulting lack of a functional immune system, the SCID/Bg mouse has been shown to accept xenografts from a range of other species [17]. As expected, it was observed that modules randomly assembled in vivo to form interconnected channels (Figure 4), but UEA-1 (specific marker for human EC) indicated limited HUVEC survival even at day 7 with an occasional darkly staining UEA-1 positive cell cluster seen out to day 21; only rarely were EC organized into microvessels and none are seen in Figure 4. Additionally, a significant host response was noted at day 7, as indicated by an increased inflammatory cell presence within the tissue surrounding the implant. Collagen-only (no HUVEC) modular implants displayed several negative characteristics, suggesting the seeded HUVEC are indeed beneficial. Specifically, collagen-only modules were unable to maintain their cylindrical shape, instead forming an indistinguishable mass of collagen upon implantation. Furthermore, in a pilot study, the implant triggered an increased host cellular response, as compared to the relatively limited inflammatory response observed with HUVEC covered modules, and collagen degradation was evident by day 3. These results are consistent with results previously found using collagen-only modules implanted into the omental pouch of nude rats [8].

Figure 4.

Histology results for (1) HUVEC-covered collagen modules and (2) collagen-only modules (no HUVEC) implanted subcutaneously in the SCID/Bg mouse and explanted at 7, 14, and 21 days. Trichrome staining shows HUVEC-covered modules randomly assembled into clusters with interconnected channels. UEA-1 (specific for human EC) indicates limited HUVEC survival at all time points. Collagen-only modules formed a single mass of collagen. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Module injection

As can be seen (Figure 5), injected modules again randomly assembled to form interconnected channels, however the extent of host cellular infiltration was reduced from that seen with module implantation (Figure 4). Additionally, the revised method appears to have caused the modules to cluster in much greater density (i.e. be less dispersed), which may be desirable for the creation of high density engineered tissue. Collagen-only modules were unable to maintain their cylindrical shape and instead formed an indistinguishable mass of collagen upon implantation, as seen earlier (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Short-term Fn-coated vs. collagen-only modules histology results. UEA-1 (specific for human EC) shows high levels of HUVEC survival in both implant types at days 1 and 3, but there was significantly reduced TUNEL staining with Fn-coated modular implants at days 1 and 3 (based on quantitative analysis). HUVEC-lined vessel-like structures appear to be perfused with host erythrocytes by day 7 in both groups. Black squares indicate relative location of high magnification images shown in Figure 6. Scale bar = 200 μm. Larger field of view shown for trichrome stained images to illustrate more of implant. HUVEC were passage 4.

Fibronectin coating

The host response over 21 days in bilateral injections in SCID/Bg mice, comparing fibronectin coated to no coating collagen modules, is shown in Figures 5, 6, 7 and 8. Quantitative results are presented in Figure 9. As expected and consistent with the in vitro results, coating the modules with fibronectin prior to HUVEC seeding resulted in decreased TUNEL staining, as compared to the HUVEC-covered collagen-only modules at days 1 and 3 (see also Figure 9B below). UEA-1 (specific for human EC) indicated very high levels of HUVEC survival at days 1 and 3 in both groups and no differences were qualitatively detected between the two implant types (Figure 5). By day 7, HUVEC viability continued within each modular construct, however survival appeared greater in the case of fibronection-coated modules. Furthermore, very little TUNEL staining was seen at day 7 and significant changes have occurred as UEA-1 positive, HUVEC-lined vessel-like structures are observed in both sites. Notably, these structures were found throughout the implanted constructs and, most importantly, appear to be perfused with host blood (Figure 6).

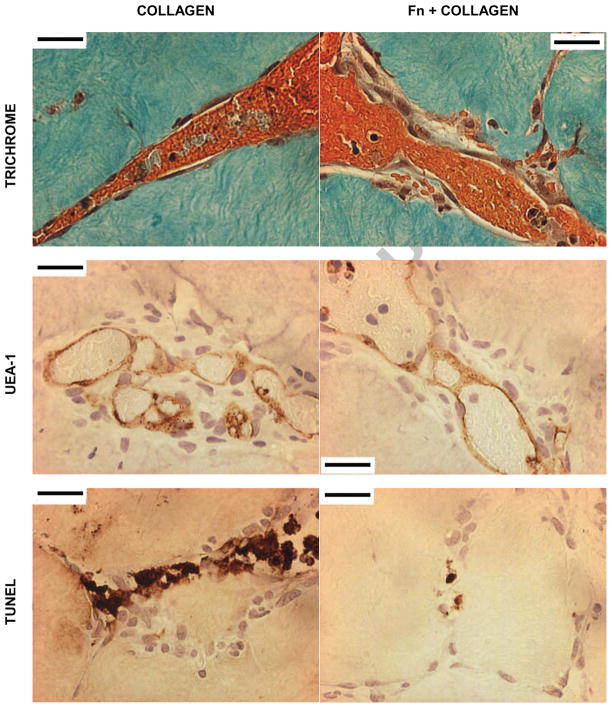

Figure 6.

High magnification (400x) images confirm the presence of host erythrocytes within the newly formed HUVEC-lined vessel-like structures by day 7. Red blood cells are clearly visible in trichrome images, while UEA-1 (specific for human EC) confirms the structures are lined with HUVEC. TUNEL staining shows persistence of low levels of apoptosis in both implant types, but quantitative analysis indicated this was lower for Fn-coated modules. Relative location of each image within the modular construct is indicated by a black square on the corresponding low magnification image shown in Figure 5. Scale bar = 25 μm. HUVEC were used at passage 4.

Figure 7.

Day 14 and day 21 Fn-coated vs. collagen-only modules histology results. UEA-1 (specific for human EC) shows HUVEC-lined vessels at day 14 and 21 in both implant types. At each time point, Fn-coated modular constructs appear to have greater vasculature density, as compared to collagen-only modules. In both implant types, the overall number of UEA-1 positive vessels is shown to increase from day 14 to 21. Trichrome images suggest perfusion of the implanted constructs, as host erythrocytes are seen within the vessel-like structures. TUNEL staining revealed negligible levels of apoptosis by day 14. Black squares indicate relative location of high magnification (400x) images shown in Figure 8. Scale bar = 200 μm. HUVEC were used at passage 4.

Figure 8.

Mature HUVEC-lined vessels were first seen at day 14 for fibronectin-coated modular constructs, and first appeared by day 21 for collagen-only modules. In both implant types, trichrome images show presence of host erythrocytes within the newly formed vasculature, which suggests perfusion. UEA-1 (specific for human EC) confirms the vessels are lined with HUVEC, while SMA reveals stabilization of the vessel walls – indicating vessel maturation. Relative location of each image series within the modular implant is indicated by a black square on the corresponding low magnification image shown in Figure 7. Scale bar = 25μm. HUVEC were used at passage 4.

Figure 9.

Quantitative analysis of in vivo HUVEC survival, apoptosis, and vessel formation. UEA-1 Chalkley grid count results (A) indicate coating collagen modules with Fn significantly increases HUVEC survival beyond day 3, while TUNEL results (B) show Fn-coating significantly reduces short-term apoptosis. Consequently, MVD counts (C) show Fn-coating increases the number of HUVEC-lined vessels by 100% at days 7 and 14. * indicates significant difference between the two implant types (p < 0.05, n = 5, paired t-test). Error bars = mean ± SEM.

Beyond day 7, greater differences were observed between the two implant types (Figure 7, Figure 9). Similar to previous literature results [18], overall HUVEC survival had decreased by day 14 in each case, but appeared to remain significantly greater where modules were coated with fibronectin. Furthermore, whereas the newly formed vessel-like structures seemed to persist and mature in the Fn-coated modular constructs (Figure 8), collagen-only modules displayed a regression in vessel numbers, as well as no observable maturation by day 14.

Finally, by day 21, the number of UEA-1 positive vessels had increased substantially at both implant sites. In fact, at this time point, vessel maturation and stabilization was also seen with the collagen-only implants (Figure 8). For the purposes of this study, vasculature stabilization was evaluated based on the presence of smooth muscle actin (SMA) positive cells (perhaps smooth muscle cells) surrounding the vessel walls. As SMA positive cell recruitment occurs during the late stages of vessel formation and their presence acts to suppress EC growth and migration, it may be presumed that HUVEC-lined vessels supported by these SMA positive cells have reached a state of maturity. Additionally, trichrome staining revealed host erythrocytes within these UEA-1 positive structures, suggesting vessel functionality. However, studies demonstrating perfusion are required to conclude this definitively.

HUVEC survival (as indicated by UEA-1 Chalkley grid count results) was significantly (p < 0.05) greater for Fn-coated modules than collagen-only modules beyond day 3 (Figure 9A). In fact, HUVEC viability was increased by approximately 30% to 45% over the day 7 to 21 time period. Although many factors influence cell response in vivo, this increased survival is speculated to be a direct result of the significantly reduced TUNEL staining detected within Fn-coated implants at both day 1 (p = 0.02) and day 3 (p < 0.01). Specifically, TUNEL Chalkley grid countswere nearly 40% lower at days 1 and 3 for Fn-coated modules, as compared to collagen-only modules (Figure 9B). These results compare favourably to those previously found in vitro (44% reduction), as well as literature data discussed below.

Finally, MVD counts (Figure 9C) confirmed significantly (p < 0.05) greater vasculature density was detected within Fn-coated vs. collagen-only modular constructs at days 7 and 14, and persisted at day 21 (however, not statistically significant at this point). These results suggest that, given enough time, HUVEC-covered collagen-only implants will generate a mature vascular system, but the process is relatively slow and inefficient to that seen with fibronectin-coated modules. Interestingly, a slight regression in HUVEC survival and UEA-1 positive vessels was noted for both implant types at day 14 and a recovery was seen by day 21. This loss and subsequent return of cell viability is similar to results previously recorded in nude mice [18].

Discussion

Several in vitro studies have shown the potential utility of the modular tissue engineering concept [7]. However, an initial in vivo study revealed poor HUVEC survival and limited persistence of newly formed blood vessels upon implantation of HUVEC-covered collagen modules into the omental pouch of nude rats [8]. The observed cell death was attributed largely to host inflammation since endothelial survival was prolonged when macrophages were depleted using clodronate liposomes. As the trauma associated with suturing the omentum was deemed responsible for the surgery-related inflammatory response, a subcutaneous implant site was chosen for the present study. In addition, the immune-compromised SCID/Bg mouse was used since this was a more commonly used host for human endothelial cell experiments and there was concern that even in the nude rat there was an immune component to the host response.

Generally, host vasculature spontaneously invades an implanted tissue in response to hypoxic signals released by the implanted cells [5]. Although this ingrowth produces such a vascular network, progress is often limited to several tenths of a micrometre per day. As a result, complete vascularisation requires weeks, during which time cell death due to hypoxia and/or nutrient deprivation occurs within the tissue. Furthermore, as graft recipients may have compromised angiogenesis due to age or diabetes, the vascularisation process may be even more prolonged [19]. Due to this severe limitation, tissue-engineered constructs are currently restricted to thin or avascular tissues, such as skin or cartilage.

Here, fibronectin was shown to significantly suppress in vitro HUVEC TUNEL staining (i.e, apoptosis, see below), as compared to collagen – both on ECM-coated TCPS, as well as on Fn-coated vs. collagen-only modules. An in vivo study confirmed the benefits of a fibronectin coating. Specifically, Fn-coated modules were found to reduce HUVEC TUNEL staining by nearly 40%, relative to that seen without fibronectin, at the 72 hours following implantation, which led to a 30% to 45% increase in long-term (7 – 21 days) vessel numbers, again relative to the collagen modules without fibronectin. Furthermore, a 100% increase in the number of HUVEC-lined vessels was observed with Fn-coated modules, as compared to collagen-only modules, at day 7 and 14. In fact, vessels appeared to be perfused with host erythrocytes by day 7. Moreover, the maturation and stabilization of newly formed Fn-coated construct vasculature was detected within 14 days, whereas similar results were not seen until day 21 for collagen-only modules.

Such results are not unprecedented in the literature. Through the in vitro prevascularisation of reconstructed skin containing EC, fibroblasts, and keratinocytes in a collagen sponge, capillary-like structures containing mouse blood were observed less than 4 days after transplantation to nude mice [20]. Similarly, a combination of HUVEC and human mesenchymal stem cells suspended in matrigel produced vessel-like structures by day 11 when subcutaneously implanted in nude mice [18].

Module injection

Initially modules were implanted through a dorsal incision, followed by the creation of a subcutaneous pocket, which was subsequently sutured to enclose the implanted modules. This led to an extensive inflammatory cell infiltration and, presumably as a consequence, limited HUVEC survival (Figure 4). It is known that surgery leads to several physiologic and immunologic changes with complex interactions between immune, metabolic, and neuroendocrine systems [21]. Furthermore, tissue trauma (such as caused by incisions) stimulates the inflammatory response in proportion to the degree of injury. As such, to limit post-operative pain and improve recovery, it is recommended that large incisions be avoided. To address this issue, the possibility of delivering modules subcutaneously through a needle was investigated. The resulting injection protocol reduced the degree of cell infiltration and increased HUVEC survival as expected (Figures 5 – 8). Furthermore, module injection appeared to cause the modules to cluster in much greater density (i.e. be less dispersed), which may be desirable for the creation of high density engineered tissue.

Suppression of HUVEC apoptosis/TUNEL staining

TUNEL staining was used as a marker of apoptosis, although further analysis of apoptotic pathways would be useful for a definitive conclusion. Presumably, by minimizing TUNEL staining (i.e., minimizing apoptosis) more HUVEC survived implantation leading to faster neo-vascularization with fibronectin coated modules; the collagen only modules were delayed in vessel formation because fewer cells survive the first 72 hours. These observations were consistent with previous literature results, at least for HUVEC without accessory cells. Specifically, it was shown that HUVEC suspended in Matrigel displayed limited short-term survival, followed by increased activity beyond 14 days, when implanted subcutaneously in the nude mouse [18]. In that study, only isolated HUVEC survival was observed at days 11 and 18, with mature vessels first appearing at day 25 in the described experiment. The authors attributed this decreased short-term survival, in part, to the time required for the ingrowth of host vasculature into the implanted construct.

Even though the revised injection protocol reduced the degree of inflammation, a pilot study indicated that HUVEC lost viability immediately after implantation, with TUNEL staining evident by 24 hours. As such, identifying a beneficial modification for the modular structure and/or cellular components was deemed critical to improving HUVEC survival, and ultimately vessel formation. Although both apoptosis and necrosis were suspected, preventing the apoptotic process was expected to moderate ischemia throughout the entire construct [9]. Co-culture of EC with other cell types (e.g. fibroblasts) has been used to exploit the beneficial interactions between cells and has been shown to support and sustain vascularisation [4]. However, as the combination of EC and functional cell types (e.g. heart, liver, pancreatic islets) is envisioned for the progression of the modular technology, avoiding the further complication of future co-culture systems was desired. Since, it had previously been demonstrated that fibronectin suppresses HUVEC apoptosis more effectively than collagen [11], we explored whether tailoring the module substrate composition would enhance HUVEC survival. Not only has fibronectin been well documented as an important substance for cell adhesion, migration, signaling, proliferation, and survival [12], but its combination with the structural properties of type I collagen fibers has already shown great promise for the formation of a HUVEC-based vasculature [13].

Adding a fibronectin coat indeed suppressed TUNELstaining in vitro for HUVEC in serum-free conditions (Figure 3) and to a less dramatic (but still significant) effect in vivo (Figure 9). Increased in vitro CHO cell survival has been correlated to the upregulation of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 promoted by activation of the fibronectin-linked α5β1 integrin [22] and presumably a similar mechanism applies here. Pathways beginning with the activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), Shc, and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) IV have each been reported to result in the elevated transcription of the Bcl-2 gene [22,23]. Interestingly, this has been shown to be independent of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, which is generally activated by most integrins, thus indicating the integrin specificity of Bcl-2 upregulation. Shc and FAK dependent activation of Ras leads to the activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway. Subsequently, Akt upregulates Bcl-2 while also inactivating pro-apoptotic proteins, Bad and caspase-9, through phosphorylation. Elevation of Bcl-2 gene transcription is accomplished through the activation of positive transcription factors, NF-κB and CREB, and the suppression of forkhead, a negative transcriptional regulator. Similarly, CaMK IV directly upregulates Bcl-2 expression through interaction with the same transcription factors and regulator. Future studies would need to confirm that similar mechanisms are operative here.

The differences in TUNEL staining, due to fibronectin coating, translated into significant differences in HUVEC survival and vessel formation (Figure 9), but there was still measureable HUVEC survival at day 7 and beyond in the collagen-only group. We were led into considering apoptosis from a pilot study with CFSE labeled passage 6 HUVEC on collagen-only modules injected subcutaneously. In this pilot study, there was almost no HUVEC survival at day 7, with the loss of HUVEC apparent as early as day 3 with concomitant TUNEL staining at days 1 and 3. This difference in results between the pilot series and the series shown in Figures 5 – 8 may be due to CFSE labeling or to HUVEC passage number. HUVEC have an increased apoptotic tendency, as well as decreased cell proliferation, from the 6th passage onwards [12]. Furthermore, early passage HUVEC have consistently shown superior in vivo vessel formation to those at later passages [13]. As such, it appears that even though passage 6 HUVEC are still considered “early stage” they may actually be more sensitive to apoptosis than passage 4 cells. This is an observation that may warrant some follow up.

Conclusion

A previous study examining the in vivo response to HUVEC-covered collagen modules implanted into the omental pouch of nude rats suggested host inflammation limited HUVEC survival beyond 3 days. Fibronectin was shown to significantly suppress in vitro HUVEC TUNEL staining, as compared to collagen – both on ECM-coated TCPS, as well as on Fn-coated vs. collagen-only modules. Moreover, a minimally-invasive surgical technique was developed, which allowed for modules to be injected subcutaneously to minimize surgery-related inflammation in a SCID/Bg mouse. In vivo, Fn-coated modules were found to reduce HUVEC TUNEL staining by nearly 40% within the first 72 hours following implantation, which led to a 30% to 45% increase in long-term (7 – 21 days) vessel numbers. Furthermore, a 100% increase in the number of HUVEC-lined vessels was observed with Fn-coated modules, as compared to collagen-only modules, at day 7 and 14. In fact, vessels appeared to be perfused with host erythrocytes by day 7. Moreover, the maturation and stabilization of newly formed Fn-coated construct vasculature was detected within 14 days, whereas similar results were not seen until day 21 for collagen-only modules.

Acknowledgments

We wish like to acknowledge the surgical expertise of Chuen Lo and the guidance of Dean Chamberlain, as well as funding provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and NIH (EB006903).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kannan RH, Salacinski K, Sales K, Butler P, Seifalian A. The roles of tissue engineering and vascularisation in the development of micro-vascular networks: A review. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1857–1875. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson P, Mikos A, Fisher J, Jansen J. Strategic directions in tissue engineering. Tissue Engineering. 2007;13:2827–2837. doi: 10.1089/ten.2007.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carmeliet P, Jain R. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249–257. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ko H, Milthorpe B, McFarland C. Engineering thick tissues – The vascularisation problem. European Cells and Materials. 2007;14:1–19. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v014a01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rouwkema J, Rivron N, van Blitterswijk C. Vascularization in tissue engineering. Trends in Biotechnology. 2008;26:434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGuigan A, Sefton MV. Vascularized organoid engineered by modular assembly enables blood perfusion. PNAS. 2006;103:11461–11466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602740103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGuigan A, Sefton MV. The thrombogenicity of human umbilical vein endothelial cell seeded collagen modules. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2453–2463. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta R, Van Rooijen N, Sefton MV. Fate of endothelialized modular constructs implanted in an omental pouch in nude rats. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2009;15:2875–2887. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saraste A, Pulkki K. Morphological and biochemical hallmarks of apoptosis. Cardiovascular Research. 2000;45:528–537. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bombeli T, Schwartz B, Harlan J. Endothelial cells undergoing apoptosis become proadhesive for nonactivated platelets. Blood. 1999;93:3831–3838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukai F, Mashimo M, Akiyama K, Goto T, Tanuma S, Katayama T. Modulation of apoptotic cell death by extracellular matrix proteins and a fibronectin-derived antiadhesive peptide. Experimental Cell Research. 1998;242:92–99. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chennazhy K, Krishnan L. Effect of passage number and matrix characteristics on differentiation of endothelial cells cultured for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5658–5667. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schechner J, Nath A, Zheng L, Kluger M, Hughes C, Sierra-Honigmann M, et al. In vivo formation of complex microvessels lined by human endothelial cells in an immunodeficient mouse. PNAS. 2000;97:9191–9196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150242297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung B, Sefton MV. A modular tissue engineering construct containing smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2007;35:2039–2049. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dejana E. Endothelial cell-cell junctions: Happy together. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2004;5:261–270. doi: 10.1038/nrm1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Milner R. Fibronectin promotes brain capillary endothelial cell survival and proliferation through a5b1 and avb3 integrins via MAP kinase signalling. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2006;96:148–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green MD, Rogers P, Russell A, Stagg Bell D, Eley S, et al. The SCID/Beige mouse as a model to investigate protection against Yersinia pestis. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 1999;23:107–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanz L, Santos-Valle P, Alonso-Camino V, Salas C, Serrano C, Vicario J, et al. Long-term in vivo imaging of human angiogenesis: Critical role of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for the generation of durable blood vessels. Microvascular Research. 2008;75:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schechner J, Crane S, Wang F, Szeglin A, Tellides G, Lorber M, et al. Engraftment of a vascularised human skin equivalent. The FASEB Journal. 2003;17:2250–2256. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0257com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tremblay P, Hudon V, Berthod F, Germain L, Auger F. Inosculation of tissue engineered capillaries with the host’s vasculature in a reconstructed skin transplanted on mice. American Journal of Transplantation. 2005;5:1002–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novitsky Y, Litwin D, Callery M. The net immunologic advantage of laparoscopic surgery. Surgical Endoscopy. 2004;18:1411–1419. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8275-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matter M, Ruoslahti E. A signaling pathway from the α5β1 and αVβ3 integrins that elevates bcl-2 transcription. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:27757–27763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102014200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee B, Ruoslahti E. α5β1 integrin stimulates Bcl-2 expression and cell survival through Akt, focal adhesion kinase, and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2005;95:1214–1223. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]